1 前言

1.1 问题提出

Clarysse和Moray (2004)曾追踪过一个创业团队。该团队由一位投资机构任命的CEO担任领导, 但是由于该CEO并不是创始成员, 且不具备与创业项目相关的技术能力, 其领导行为受到了团队成员的不断抵制, 甚至成员们拥戴另一位从创业初期就加入团队的技术领袖来挑战其领导地位。该团队因此变得混乱和绩效低下。Magee和Galinsky (2008)指出权力(power)和地位(status)是形成社会层级的两个最基本维度, 权力是个体对重要资源的不对称占有, 地位则是个体受到他人尊重和敬仰的程度。这两个维度会出现不一致的情况, 即个体可能拥有高权力但缺乏地位, 或拥有高地位但缺乏权力, 且这种不一致并不罕见(Blader & Chen, 2014)。正如本文开头所提的创业团队的案例, 投资机构任命的团队负责人拥有正式的权威但并不受人爱戴(高权力/低地位), 而作为其下属的技术领袖则受到其他团队成员的尊敬和推崇(低权力/高地位)。

权力层级(power hierarchy)是根据个体拥有重要资源的差异而形成的等级秩序(Magee & Galinsky, 2008), 其对于团队内的人际互动和组织运作有着重要影响(Bunderson & Reagans, 2011; Fiske, 1992; Greer, 2014)。目前相关研究大多认同权力层级的重要性, 但关于权力层级对团队绩效的作用依然存在明显的分歧(Tarakci, Greer, & Groenen, 2016)。持功能主义观点的学者认为权力层级可以促进团队内的协调, 进而有利于团队绩效(e.g., Halevy, Chou, Galinsky, & Murnighan, 2012; Ronay, Greenaway, Anicich, & Galinsky, 2012)。而功能障碍主义者认为权力层级会引发团队内冲突, 不利于团队绩效(e.g., Bloom, 1999; Mannix, 1993)。为了化解这两派的矛盾, 一些研究开始探索权力层级与团队绩效关系的权变因素(e.g., Ronay et al., 2012; Tarakci et al., 2016; van der Vegt, de Jong, Bunderson, & Molleman, 2010)。但这些研究都默认团队内权力层级与地位层级是高度一致的, 忽略了权力层级和地位层级不一致对权力层级与团队绩效关系的潜在影响。

我们认为, 之所以功能主义和功能障碍主义存在截然相反的逻辑和实证证据, 可能是因为以往研究忽略了层级一致性(hierarchical consistency)对权力层级与团队绩效关系的影响。层级一致性指的是团队内地位层级与权力层级的匹配程度(Halevy, Chou, & Galinsky, 2011)。当地位层级与权力层级一致时, 会增强权力层级的合法性(Magee & Galinsky, 2008), 从而有利于削弱团队内权力争夺和提升团队绩效; 而当地位层级与权力层级不一致时, 权力层级的合法性受损, 从而激发了团队内权力争夺并削弱了团队绩效(本研究理论模型见图1)。基于上述观点, 本文将结合问卷、实验和二手数据三种方法来探索层级一致性对权力层级与团队绩效关系的调节作用, 以及权力争夺在权力层级和层级一致性的交互与团队绩效的关系中的中介作用。我们的研究对相关领域具有一定的贡献, 本研究首次在团队水平提出并检验了层级一致性对权力层级与团队绩效关系的影响, 进而有利于化解目前团队层级研究领域中功能主义与功能障碍主义的冲突, 并拓展了关于层级一致性和权力层级合法性的研究。

图1

1.2 权力层级与团队绩效:分歧的结论与证据

关于权力层级对团队绩效的作用, 相关研究已经分裂成两个对立的流派, 即强调权力层级积极作用的功能主义与强调权力层级消极作用的功能障碍主义。功能主义者认为权力层级明确了成员间的支配和服从关系(e.g., Anicich, Swaab, & Galinsky, 2015; Gruenfeld & Tiedens, 2010; Keltner, van Kleef, Chen, & Kraus, 2008), 有利于抑制团队内冲突和促进合作与协调(Bendersky & Hays, 2012; Bunderson, van der Vegt, Cantimur, & Rink, 2016)。有许多实证研究支持层级功能主义的观点。例如, Halevy等学者(2012)通过对11个赛季的北美职业篮球联赛数据进行研究发现, 团队内基于薪酬和选秀顺位形成的权力层级可以促进团队内的协调与合作, 进而提升球队胜率。

与层级功能主义相对立, 功能障碍主义者认为权力层级不利于团队绩效。功能障碍主义根据社会公平理论(Adams, 1965), 认为低权力者将自身对团队的贡献和获得的权力与高权力者进行比较时容易产生不公平感 (Anderson & Brown, 2010)。这种不公平感激发团队成员对于现有权力秩序的不满和层级敏感性, 从而造成团队内的权力争夺和冲突(Greer, Caruso, & Jehn, 2011; Greer, van Bunderen, & Yu, 2017; Mannix, 1993)。支持功能障碍主义观点的实证研究也不是少数。例如, Bloom (1999)通过对北美职业棒球联盟的二手数据进行研究发现, 球队内的薪酬差异对团队绩效起消极作用, 并且其指出这种消极作用源于层级对合作的破坏。

从上面的综述可以看出, 以往研究存在明显的分歧。本文认为以往研究的分歧很可能源于忽略了权力层级与地位层级一致性的差异对权力层级与团队绩效关系的影响。

1.3 权力与地位:被忽略的层级一致性

Magee和Galinsky (2008)指出权力和地位是社会层级的两个基本维度, 权力是对重要社会资源的不对称占有, 而地位是被他人尊重或敬仰的程度。该观点得到了众多研究的采纳和支持(e.g., Anicich, Fast, Halevy, & Galinsky, 2016; Fast, Halevy, & Galinsky, 2012; Hays, 2013)。权力通常基于个体对于资源和机会的占有, 以及命令、惩罚或奖励他人的能力; 而地位则通常基于专长、能力和声誉(Blader, Shirako, & Chen, 2016; 胡琼晶, 谢小云, 2015; Magee & Galinsky, 2008)。本文采纳Magee和Galinsky (2008)对层级的定义, 即将层级分为权力层级和地位层级两类, 地位层级是个体间基于获得他人尊重的差异形成的等级秩序, 权力层级是个体间对于重要资源占有的差异形成的等级秩序。

以往研究大多默认权力和地位是高度一致的, 但权力和地位不一致的现象实际上并不罕见(Blader & Chen, 2014; Luan, Hu, & Xie, 2017)。个体可能拥有大量资源却无法得到他人的尊重(高权力/低地位), 也可能缺乏重要资源但深受人们尊重和爱戴(低权力/高地位) (Magee & Galinsky, 2008)。近期已有个体层面的研究开始关注这种层级不一致现象, 并初步探索了权力和地位不一致对个体人际行为的影响(e.g., Anicich et al., 2016; Blader & Chen, 2012; Fast et al., 2012)。此外, Ma, Rhee和Yang (2013)在组织层面的研究发现战略联盟双方所有权(权力)和地位的匹配有利于战略联盟的绩效。但以往权力层级与团队绩效的相关研究却忽略了权力层级与地位层级的一致性可能存在的差异。

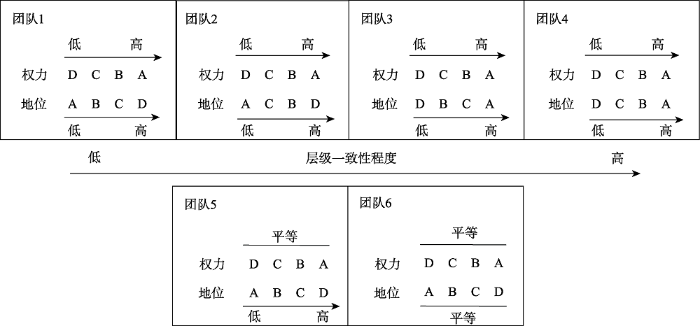

本研究将层级一致性定义为团队中权力层级与地位层级的匹配程度。其在操作层面指的是团队内各成员权力与地位的平均匹配程度。如图2所示, 在一个团队中, 权力层级与地位层级可能是完全一致的, 即如团队4所示, 高权力者同时拥有高地位, 低权力者拥有低地位; 权力层级与地位层级也可能完全不一致, 即如团队1所示, 高权力者拥有低地位, 低权力者拥有高地位。除了以上提到的层级完全匹配和完全不匹配这两种极端情况外, 层级一致性也会表现出匹配程度的差异。即在一些团队中团队成员所拥有的权力和地位大致是匹配的, 如团队3; 而在另一些团队中则可能出现部分团队成员的权力和地位较大程度上不匹配, 如团队2, 此时前者的层级一致性的程度就比后者更高。即使在团队内权力平等的情况下, 层级一致性依然可能存在差异, 如团队5的层级一致性程度就低于团队6。这种层级一致性的差异可能会影响权力层级对团队绩效的作用(Halevy et al., 2011), 但在以往的研究中被忽略了。因此本研究将探索层级一致性对权力层级与团队绩效关系的影响。

图2

1.4 理论与假设

根据合法性理论(legitimacy theory), 权力层级的有效性取决于其合法性; 当个体认为权力层级合理和公正时会自愿接受和顺从层级安排, 而当其认为权力层级不合法时则可能采取反抗和抵制的行为(Tyler, 2006)。层级一致性会影响权力层级的合法性感知, 进而影响权力层级效应的发挥(Magee & Galinsky, 2008)。例如, 当占有团队内重要资源(高权力)的个体并不受人尊敬和敬仰(低地位), 而受到众人尊敬和敬仰(高地位)的个体却缺乏资源与机会(低权力)时, 团队成员会认为这样的权力层级是不合法的; 反之, 当团队内成员所拥有的资源与其受尊重的程度都匹配时, 权力层级的合法性较高。当权力层级的合法性水平高时, 可以有效减弱团队内的摩擦和冲突, 对团队绩效有利; 而权力层级缺乏合法性时则容易引发团队内的争夺与冲突, 会对团队绩效产生不利影响(Halevy et al., 2011)。因此我们提出如下假设:

假设1:层级一致性调节了权力层级与团队绩效的关系, 当层级一致(地位层级与权力层级匹配)时, 权力层级有利于团队绩效, 当层级不一致(地位层级与权力层级不匹配)时, 权力层级不利于团队绩效。

团队内权力争夺(power struggle)指的是团队成员为了占有团队内重要资源而展开的争夺(Greer & van Kleef, 2010; Greer et al., 2017)。我们认为权力层级与层级一致性的交互通过权力争夺影响团队绩效。如上所述, 层级一致性影响了权力层级的合法性感知。当权力层级具备合法性时, 权力层级促使团队成员将自身的层级角色内化, 更倾向于自愿地接受和顺从高权力者制定的规范和命令, 从而抑制了团队内的摩擦和冲突(Halevy et al., 2011; Tyler, 2006)。相关的实证研究为此观点提供了支持, 例如, Baldassarri和Grossman (2011)通过对乌干达50个农业合作组织的1543名农民的现场实验发现, 合法的权力秩序相对于不合法的权力秩序更有利于促进合作行为。当权力层级缺乏合法性时, 团队成员不愿接受和依从高权力者制定的决策和规则, 并可能采取反抗和挑战的态度(Fiske, 2010; Tyler, 2006)。如表1中的团队4所示, 当层级不一致时, 团队内同时存在一位高权力/低地位成员与一位低权力/高地位成员, 此时低权力/高地位成员很难依从高权力/低地位成员的领导。例如, Clarysse和Moray (2004)的一项对创业团队的定性研究曾发现, 某创业团队内同时存在一位拥有权力的正式领导(CEO)和一位得到团队成员尊重的非正式领导, 两者在团队内不断争夺影响力, 其他团队成员也抵制和应付正式领导的命令, 使得正式领导的作用受到了非正式领导的严重制约。相关研究还发现, 当权力层级不合法时, 低权力者会更倾向于从事具有风险的行为(Lammers, Galinsky, Gordijn, & Otten, 2008), 更加地目标导向(Willis, Guinote, & Rodríguez- Bailón, 2010)和不遵守社会规范(Hays & Goldstein, 2015)。因此我们提出如下假设:

假设2:层级一致性调节了权力层级与权力争夺的关系, 当层级一致时, 权力层级会削弱权力争夺, 当层级不一致时, 权力层级会增强权力争夺。

表1 权力层级与层级一致性的组合

| 团队1 | 权力平等& 层级一致 | 团队2 | 权力不平等& 层级一致 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 团队成员 | 权力 | 地位 | 团队成员 | 权力 | 地位 |

| A | 中 | 中 | A | 高 | 高 |

| B | 中 | 中 | B | 中 | 中 |

| C | 中 | 中 | C | 低 | 低 |

| 团队3 | 权力平等& 层级不一致 | 团队4 | 权力不平等& 层级不一致 | ||

| 团队成员 | 权力 | 地位 | 团队成员 | 权力 | 地位 |

| A | 中 | 高 | A | 高 | 低 |

| B | 中 | 中 | B | 中 | 中 |

| C | 中 | 低 | C | 低 | 高 |

进一步, 我们认为团队成员间的权力争夺会破坏团队内的合作, 并引发团队成员间的冲突, 进而损害团队绩效。权力是一个基于对于重要资源的相对占有数量的结构属性(Magee & Galinsky, 2008), 因此团队内一个成员权力的提升可能意味着其他成员权力的下降。权力争夺是团队成员为了团队内重要资源的相对控制权而展开的争夺(Greer & van Kleef, 2010), 权力争夺参与者都以提升自身的相对资源数量为目标, 显然他们彼此间的目标是相互抵触的。当团队成员间的目标相互抵触时, 他们会努力实现自己的目标并阻碍他人目标的实现(Deutsch, 1949, 2014; Johnson & Johnson, 2005), 此时团队成员间的合作会遭到破坏(Deutsch, 1949)。例如, 相关研究发现, 团队成员间对于层级位置的分歧和争夺会导致团队成员减少对团队任务的投入(Kilduff, Willer, & Anderson, 2016), 并抑制团队内的信息分享(Bendersky & Hays, 2012)。此外, 在权力争夺过程中团队成员会采取强制、威胁和欺骗等策略, 进而激发了团队内的冲突(Deutsch, 2014)。例如, 一些研究发现团队内的权力争夺会激化政治行为, 团队成员开展的结盟、监视和背叛等政治活动会进一步激化团队内的矛盾(e.g., Eisenhardt & Bourgeois, 1988)。能否有效的促进团队内的合作并抑制团队内的冲突对于提升团队绩效至关重要(Deutsch, 2014; Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp, & Gilson, 2008)。相关的实证研究与元分析也发现团队合作可以积极的促进团队绩效(e.g., Halevy et al., 2012; Stewart, 2006), 而团队冲突则会对团队绩效产生消极的结果(e.g., Bendersky & Hays, 2012; De Dreu & Weingart, 2003)。此外, Greer和van Kleef (2010)的实证研究已经直接验证了权力争夺对团队绩效的负向作用。

综上所述, 当层级一致时, 权力层级具备合法性, 从而有利于减弱团队内的权力争夺; 当层级不一致时, 权力层级缺乏合法性, 会激发了团队内的权力争夺。权力争夺则会破坏团队内的合作并激发团队内的冲突, 进而对团队绩效产生消极影响。因此我们提出如下假设:

假设3:权力争夺在权力层级和层级一致性的交互与团队绩效的关系中起中介作用。

接下来本研究将结合问卷调查、实验和二手数据分析这三种研究方法, 并采用不同类型的样本来验证所提的假设。

2 研究1:权力层级与团队绩效的关系——层级一致性的调节作用

首先我们通过一项针对大学生创业实践团队的问卷调查来验证层级一致性对权力层级与团队绩效关系的调节作用。我们在一所中部高校的创业实践课程中开展了此项研究。这项创业实践课程为期四周, 管理类专业的大三学生全天候(每天8小时)地参与本项实践课程。在该项课程中, 所有团队独立地开展成立虚拟公司、市场调研、现场销售等经营活动, 且各团队组建的虚拟公司会在校内创业孵化园区中真实地开展经营活动, 经营活动所需的资金全部由每个团队自筹, 相应地, 经营所获得的全部经济收益也归团队自身所有。这项创业实践课程中的团队在开展团队任务时具有较大的自主性, 拥有共同的任务目标, 非常适合作为团队研究的样本。此外, 这些团队的创业实践项目是真实运营的, 并且每个团队都提交了统一格式的经营财务报表, 从而为衡量团队绩效提供了较为可靠的客观指标。

2.1 样本

共有352名管理类专业(市场营销、营销策划、工商管理)的大三学生参与了本项研究, 参与者的平均年龄为20.67岁(SD = 0.87岁), 其中52.48%为男性, 47.52%为女性, 参与者平均有6.58个月(SD = 10.45)的课外兼职工作经验。5到10名参与者自由组成团队开展创业实践任务, 共有46个团队参与了本项研究, 并且46个团队的所有成员均填写了问卷。

2.2 过程

任务团队通常需要一段时间的互动来建立起团队中的层级(Berger, Cohen, & Zelditch, 1972), 因此我们在创业实践课程开始两周后发放问卷, 问卷中每个团队成员都需要评价同一团队内其他成员的权力和地位。随后, 我们收集创业实践课程结束时(即问卷回收完成的两周后)各团队提供的客观财务数据来衡量团队绩效, 通过时间上的滞后安排以及不同的数据来源, 从而有效降低了共同方法偏差对本研究结果的影响(Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003)。

2.3 测量

由于本研究采用的量表最初是用英文开发的, 我们遵循了双向互译过程(Brislin, 1980)将量表翻译成了中文。我们遵循以往相关研究的程序(Cantimur, Rink, & van der Vegt, 2016; Hays & Bendersky, 2015), 对权力和地位采用轮转法(round-robin)的程序进行测量, 即每个团队成员都对除了自身以外的其他团队成员的权力和地位进行评价。此外, 由于每个团队成员的权力和地位的评分都由其他团队成员对其的评分聚合而成, 为了检验数据聚合的可行性, 我们计算了内部一致性系数(ICC) (James, 1982)。

权力。我们采用Hays和Bendersky (2015)开发的2个题项的量表1( 原量表即为两个题项, 具体可参考原文(Hays & Bendersky, 2015, P. 875)。)来测量权力。所有团队成员都对其他团队成员在团队内的“权力水平”进行评价, 这2个题项分别是“他/她多大程度上控制着团队中重要的资源”和“他/她在团队中拥有多大的权力”, 参与者对这2个题项用5点李克特量表进行打分。该量表的Cronbach's α为0.81, 显示该量表拥有良好的信度。ICC (1)为0.22, ICC (2)为0.68, 显示评分的组内一致性较强。

地位。我们采用Blader等学者(2016)开发的2个题项的量表2(2 原量表即为两个题项, 具体可参考原文(Blader et al., 2016, P. 732)。)来测量地位。所有团队成员都对其他团队成员在团队内的“地位水平”进行评价, 这2个题项分别是“他/她在团队中得到多大程度的尊敬”和“他/她在团队中拥有多高的地位(敬仰和尊重)”, 参与者对这2个题项用5点李克特量表进行打分。该量表的Cronbach's α为0.83, 显示该量表拥有良好的信度。ICC (1)为0.19, ICC (2)为0.65, 显示评分的组内一致性较强。

权力层级。首先, 我们对每个团队成员的权力的他评分数求均值, 从而得出每个团队成员的权力分值。之后, 我们再将个体水平的权力分值聚合到团队, 形成团队权力层级的分值。为了与以往的研究(e.g., Cantimur et al., 2016; Greer & van Kleef, 2010; Halevy et al., 2012)保持一致, 我们采用团队成员间权力的标准差来计算权力层级; 标准差的值越大, 代表团队内的权力越不平等。

层级一致性。为了计算层级一致性, 我们首先计算出每个团队成员权力和地位之差的绝对值, 然后对权力和地位之差的绝对值进行组内平均, 最后将得出的均值取负数即代表各团队的层级一致性, 当数值越小时则表示层级一致性水平越低。类似的测量方法曾被用于其他群体层面的一致性或匹配性的研究中(e.g., Kunze & Menges, 2017)。

团队绩效。我们用各团队经营的创业项目所获得的实际经济利润来衡量团队绩效。在创业实践课程结束时各团队必须提交自己团队的财务报表, 财务报表会列出成本、收入和利润等情况。我们观察到个别团队采用了低利润率来扩大销量的经营策略, 还有些团队获得了高额的经营收入但是由于成本过高导致了亏损, 为了削弱这些因素的影响, 我们用各团队的实际利润而非总收入来衡量绩效。

控制变量。以往研究结果显示团队规模对团队绩效有显著的影响(Lepine, Piccolo, Jackson, Mathieu, & Saul, 2008), 因此在本研究中我们对团队规模进行了控制。同样地, 为了排除团队平均年龄(Streufert, Pogash, Piasecki, & Post, 1990)、性别多样性(Campbell & Mínguez-Vera, 2008)和熟悉度多样性(Avgerinos & Gokpinar, 2017)对团队绩效的影响, 在本研究中我们对团队平均年龄、熟悉度多样性和性别多样性也进行了控制。其中性别多样性的计算采用Blau系数, 计算熟悉度多样性采用标准差(Harrison & Klein, 2007)。Harrison和Klein (2007)指出在研究权力层级这种组内差异性(disparity)属性的变量时需要控制该变量的均值, 因此在分析时我们还控制了团队的权力均值和地位均值。

2.4 结果

从表2中可以看到, 与我们的预测一致, 权力层级与团队绩效并没有显著的相关性。我们通过多元回归分析来验证层级一致性是否在权力层级与团队绩效的关系中起调节作用。

表2 变量均值、标准差和相关系数

| 变量 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 团队规模 | 7.65 | 1.10 | - | |||||||

| 2 平均年龄 | 20.67 | 0.41 | -0.14 | - | ||||||

| 3 熟悉度多样性 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.25 | - | |||||

| 4 性别多样性 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.37* | 0.03 | 0.08 | - | ||||

| 5 团队权力均值 | 3.37 | 0.38 | -0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 | - | |||

| 6 团队地位均值 | 3.63 | 0.38 | -0.02 | -0.16 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.78** | - | ||

| 7 权力层级 | 0.29 | 0.12 | -0.09 | -0.17 | 0.02 | -0.14 | -0.30** | -0.20 | - | |

| 8 层级一致性 | -0.34 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.14 | -0.42** | -0.20 | - |

| 9 团队绩效 | 293.66 | 483.93 | 0.20 | -0.17 | 0.16 | 0.13 | -0.12 | 0.01 | -0.17 | -0.16 |

注:n = 46. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01。

在将变量加入回归方程前, 为了应对可能的多重共线性问题, 我们对所有预测变量进行了中心化处理; 此外, 由于团队绩效的均值和标准差远远大于其他变量的均值与标准差, 为了缩小团队绩效在量纲和变异上与其他变量的差异, 我们对其进行了标准化处理(Rodgers & Nicewander, 1988; Rovine & von Eye, 1997)。我们在假设1中提出权力层级与团队绩效的关系受到层级一致性的调节; 从回归分析的结果看(见表3), 模型2(M2)显示权力层级对团队绩效的作用不显著(b = -2.39, ns, t = -1.77), 而在模型3(M3)中, 权力层级与层级一致性的交互对团队绩效的作用显著(b = 12.20, p < 0.05, t = 2.06), 说明权力层级对团队绩效并没有显著的主效应, 而层级一致性调节了权力层级与团队绩效的关系, 因此假设1得到支持。

表3 多元回归分析结果

| 变量 | 团队绩效 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | |

| 控制变量 | |||

| 团队规模 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| 平均年龄 | -0.41 | -0.58 | -0.81 |

| 熟悉度多样性 | 0.77 | 0.97 | 1.13 |

| 性别多样性 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 1.04 |

| 团队权力均值 | -0.62 | 0.33 | 0.51 |

| 团队地位均值 | 0.42 | -0.91 | -1.12 |

| 主效应 | |||

| 权力层级 | -2.39 | -1.88 | |

| 层级一致性 | -1.95 | -2.05 | |

| 调节效应 | |||

| 权力层级 × 层级一致性 | 12.20* | ||

| R2 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.28 |

| F | 0.85 | 1.12 | 1.56 |

| ΔR2 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.09* |

注:n = 46. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; 因变量为标准化后的团队绩效, 各模型中的回归系数均为非标准化的回归系数。

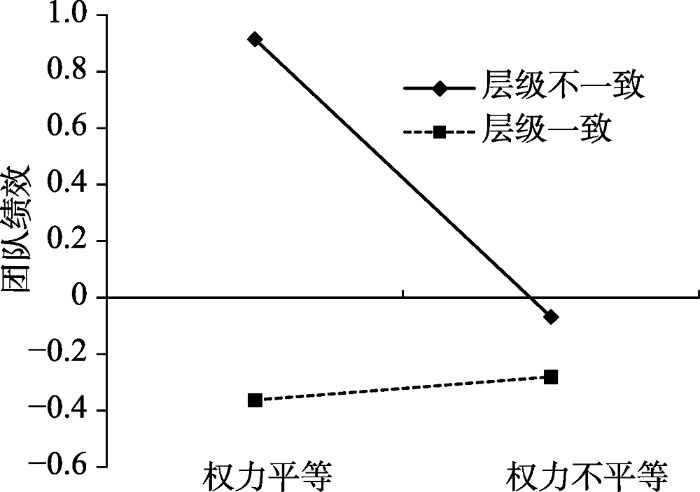

我们通过简单效应分析进一步验证层级一致性对于权力层级与团队绩效关系的调节作用, 并对不同层级一致性水平下权力层级与团队绩效的关系进行了绘图(见图3)。当层级一致性由低到高时, 代表权力层级与团队绩效的关系的直线从斜率为负且显著(k = -4.10, p < 0.05), 变为斜率为正但是不显著(k = 0.34, ns)。说明地位层级与权力层级不一致时, 权力层级与团队绩效负相关, 而当地位层级与权力层级一致时, 权力层级与团队绩效的关系不显著, 因此假设1得到了部分支持。

图3

最后, 我们将采用不同的层级操作化指标对本研究的发现进行稳健性检验。过去的层级研究曾采用变异系数(e.g., Hays & Bendersky, 2015), 基尼系数(e.g., Bloom, 1999), 以及中心化系数(e.g., Huang & Cummings, 2011)这三个指标来操作化层级, 因此本研究分别采用这三个指标来进行稳定性检验。我们在保持其他变量不变的前提下, 分别用团队成员权力的变异系数、基尼系数和中心化系数来代替原有的权力层级变量加入检验调节效应的回归模型中, 得到的交互作用与采用标准差得到的结果类似(采用变异系数:b = 32.21, p < 0.10, t = 1.80; 采用基尼系数:b = 72.16, p < 0.10, t = 1.94; 采用中心化:b = 26.06, p < 0.05, t = 2.19)。这三个检验的结果显示本研究的发现具有较强的稳健性。

研究1基本验证了我们的假设1, 结果显示层级一致性调节了权力层级与团队绩效的关系, 当层级不一致时权力层级负向影响团队绩效, 但与我们预测不一致的是当层级一致时权力层级与团队绩效没有显著的关系。采用相同任务周期, 类似团队任务的团队作为样本, 以及采取时间间隔的设计和客观指标衡量绩效, 这些都增强了研究1的内部效度。但是作为一项基于问卷调查的相关研究, 无法真正检验因果逻辑, 并且在研究1中并没有检验权力层级与层级一致性的交互影响团队绩效的作用机制。为了应对这些不足, 我们接下来开展了一项实验研究。

3 研究2:权力层级与团队绩效的关系——层级一致性的调节作用以及权力争夺的中介作用

研究2的目的是验证我们所提的中介假设, 并且通过实验方法验证本研究的因果逻辑, 增强整个研究的内部效度。

3.1 样本

来自东部一所大学的192名大学生参与了本实验, 本实验随机分配三名同性别的参与者作为一个团队共同参与实验任务, 即共有64个三人团队参与了本实验。参与者平均年龄为22.29岁(SD = 2.44); 其中55.7%为本科生, 44.3%为研究生, 所有参与者中59.4%为女性, 40.6%为男性。参与者是以“团队商业决策研究”的名义在学校论坛公开招募的, 每位参与者均自愿参与本实验, 且每位参与者会获得30元人民币的报酬。此外, 为了激励参与者在实验任务中兼顾个人利益与团队目标, 我们在招募被试以及实验材料中明确说明, 绩效最优的一个三人团队以及三个个人可以获得每人100元人民币的额外奖励, 并在所有场次的实验结束后兑现了额外奖励。

3.2 实验任务

我们改编了Greer和van Kleef (2010)的多人谈判任务作为实验任务。这个任务贴近了组织中常见的团队任务, 并且其反映了团队成员的混合动机(mixed-motives), 即追求自身利益又希望团队成功(van Bunderen, Greer, & van Knippenberg, 2018), 同时也有利于考察团队内的权力争夺过程(Greer & van Kleef, 2010)。每个实验团队被告知他们将作为ABC咨询公司的一个咨询团队开展项目——为通达快递公司提供绩效改进方案(实际上只完成关于项目任务的六项前期事项决策)。他们在提供改进方案前先需要对项目启动时间、与客户交流联系频率和方式、给予顾客的培训次数等六项事宜进行决策, 每个事宜的决策结果关系到个人能获得的资源点数的多少, 资源点数则可以用于提升个人绩效。表4显示了各角色在前三项决策选项上能获得的资源点数, 在真实的实验材料中每个参与者只获得自己扮演角色相关的资源点数列表, 而无法获知其他成员相应的资源点数。从表4可以看到, 每个团队成员从这六项决策中能够获得的资源点数是不同的, 且我们在实验中规定不能将自身在每项决策中能够获得的个人资源数量透露给其他团队成员。在每项事宜的决策上, 可以由三个团队成员协商一致来决定, 也可以通过行使“一票决定权”强行将自己的选择作为团队决策的结果, 每个团队被要求在15分钟内做出这六项决策, 否则所有成员获得的资源点都为零。

表4 实验任务材料

| 议题 | 选项 | 资源(咨询师A) | 资源(咨询师B) | 资源(咨询师C) | 资源 总数 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 议题1: 项目启动时间 | 1周后 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 2周后 | 75 | 25 | 25 | 125 | |

| 3周后 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 150 | |

| 4周后 | 25 | 75 | 25 | 125 | |

| 5周后 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | |

| 议题2: 对顾客进行访谈的次数 | 2次 | 0 | 75 | 25 | 100 |

| 4次 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 150 | |

| 6次 | 75 | 0 | 25 | 100 | |

| 议题3: 对客户进行培训的时长 | 9小时 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| 12小时 | 25 | 25 | 75 | 125 | |

| 15小时 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 150 | |

| 18小时 | 75 | 25 | 25 | 125 | |

| 21小时 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

3.3 实验设计和程序

实验采用2(权力层级:不平等vs.平等)×2(层级一致性:地位层级与权力层级不一致 vs.地位层级与权力层级一致)组间设计。参与者被随机分配到不同的实验条件, 而为了避免性别对权力和地位的可能影响(Hays, 2013), 每个实验团队由同性别的三位参与者组成。当每个实验团队的参与者到齐后, 每位参与者被要求首先独自阅读实验的指导语和实验任务材料, 并且完成一份关于管理咨询知识的测试试卷, 试卷完成后实验者会进行批改并当场公布测试成绩(假反馈, 用于操纵层级一致性), 并再次强调每个团队成员各自拥有“一票决定权”的数量; 之后参与者被要求以团队的形式在15分钟内完成多人谈判任务; 在完成谈判任务后每位参与者独自填写一份关于人口统计信息和操作检验的问卷并给予实验报酬。

3.4 实验操纵和测量

权力层级和层级一致性。我们通过操作团队成员拥有团队中重要资源的数量的差异来操作权力层级, 用操作团队内权力与地位的匹配程度来操作层级一致性。由于权力层级与层级一致性都是团队水平的构念, 我们像其他团队水平的层级研究一样, 在操作个体权力/地位的基础上来操作团队水平的层级结构与层级一致性(e.g., Greer & van Kleef, 2010; Ronay et al., 2012)。实证研究发现, 权力通常基于个体对于资源和机会的占有, 以及命令他人的能力; 而地位则通常基于技能和专长(Blader et al., 2016)。因此本研究用团队成员间决策权的差异来操作权力差异, 而用技能和专长的差异来操作地位差异。具体地, 我们用团队成员拥有“一票决定权”的数量来操作权力差异, 当团队成员行使“一票决定权”时, 其可以在不经过其他团队成员同意的情况下直接以团队的名义进行决策。高权力者通过实验的指导语被告知其拥有三次“一票决定权”, 中权力者有两次, 低权力者只有一次。其次, 我们用 “管理咨询知识”测试的成绩来操纵地位, 因为测试成绩的高低代表了参与者在管理咨询任务上的专长水平。参与者首先被要求完成一个简短的管理咨询知识测试, 之后实验者当面批改并公开发布成绩排序。高地位者会被告知其在团队成员中获得了最高的成绩, 低地位者获得了最低的成绩, 而中地位者测试成绩在高地位和低地位者之间。

接下来根据团队成员权力与地位的匹配来操作权力层级与层级一致性。例如, 在权力不平等与层级一致水平下, 三名成员分别扮演咨询师A、咨询师B和咨询师C的角色; 咨询师A获得三次“一票决定权”且在“管理咨询知识测试”中得分最高, 咨询师B获得两次“一票决定权”且在“管理咨询知识测试”中得分中等, 咨询师C获得一次“一票决定权”且在“管理咨询知识测试”中得分最低。其他实验水平的操作具体如表5所示。

表5 权力层级与层级一致性的操作

| 团队1 | 权力平等& 层级一致 | 团队2 | 权力不平等& 层级一致 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 团队 成员 | 一票 决定权 | 测试 成绩 | 团队 成员 | 一票 决定权 | 测试 成绩 |

| A | 2 | 中 | A | 3 | 高 |

| B | 2 | 中 | B | 2 | 中 |

| C | 2 | 中 | C | 1 | 低 |

| 团队3 | 权力平等& 层级不一致 | 团队4 | 权力不平等& 层级不一致 | ||

| 团队 成员 | 一票 决定权 | 测试 成绩 | 团队 成员 | 一票 决定权 | 测试 成绩 |

| A | 2 | 高 | A | 3 | 低 |

| B | 2 | 中 | B | 2 | 中 |

| C | 2 | 低 | C | 1 | 高 |

权力争夺和团队绩效。我们用团队内“一票决定权”使用的总次数来测量权力争夺。权力争夺是团队成员为了获取团队内重要资源而展开的争夺(Greer & van Kleef, 2010)。通过使用“一票决定权”, 参与者可以在未得到其他团队成员认可的情况下获取资源点数, 而团队内使用“一票决定权”的数量越多, 就说明团队内争夺重要资源的程度越激烈。因此, 团队使用“一票决定权”的总次数从总体上反映了团队内权力争夺的水平。团队绩效用团队成员获得资源点数之和来测量, 因为其反映了团队冲突解决的质量(Greer & van Kleef, 2010)。团队通过多人谈判任务所获得资源点数之和越多, 则团队绩效越高。

3.5 实验结果

操作检验。我们采用Hays和Bendersky (2015)的2题项权力量表和3题项地位量表分别对权力和地位的实验操作进行检验。权力量表的例题:“我控制着团队中重要的资源”; 地位量表的例题:“我在团队中受到多少尊重”。从单因素方差分析的结果看, 权力的操作显著地影响了操作检验的结果, F(2, 189) = 48.47, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.34; 高权力组(M = 4.05, SD = 0.73)对自身权力的感知显著高于中权力组(M = 3.43, SD = 0.60)和低权力组(M = 2.44, SD = 0.84)。地位的操作也显著地影响了操作检验的结果, F(2, 189) = 4.39, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.04, 高地位组(M = 3.42, SD = 0.69)对自身地位的感知显著高于低地位组(M = 3.08, SD = 0.55), 且高地位组对地位的感知高于中地位组(M = 3.29, SD = 0.52), 但两者的差异并不显著。

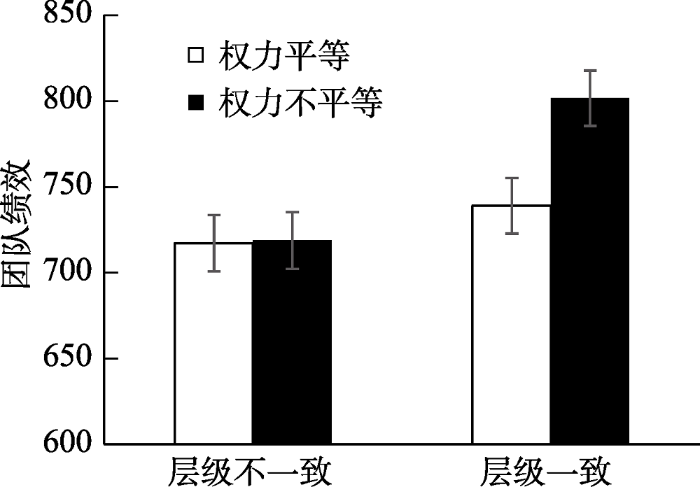

假设检验。我们在假设1中提出层级一致性调节了权力层级与团队绩效的关系。从方差分析的结果来看, 在控制了团队的平均年龄后, 权力层级和层级一致性对团队绩效的交互效应是显著的, F(1, 59) = 4.34, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.07, 因此假设1得到支持。我们对交互作用进行进一步的简单效应分析, 结果显示(见图4), 当层级一致时, 权力层级对于团队绩效的主效应显著, F(1, 59) = 14.39, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.10; 当层级不一致时, 权力层级对于团队绩效的主效应不显著, F(1, 59) = 0.72, ns。

图4

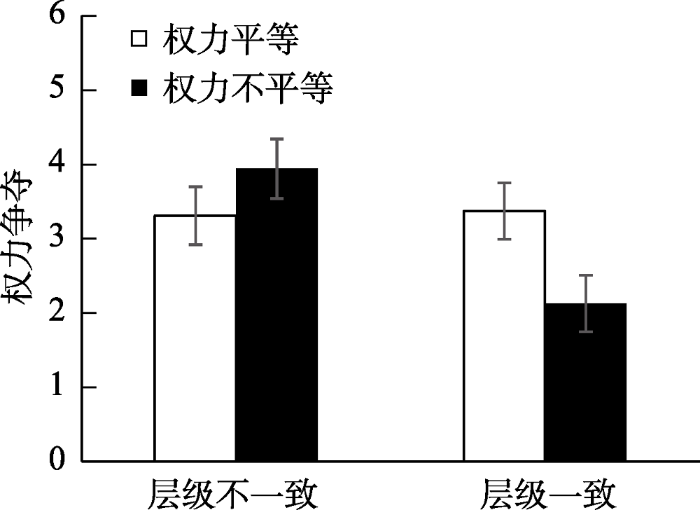

我们在假设2中提出层级一致性调节了权力层级与权力争夺的关系。从方差分析的结果来看, 在控制了团队的平均年龄后, 权力层级和层级一致性对权力争夺的交互效应是显著的, F(1, 59) = 15.13, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.10。我们对交互作用进行进一步的简单效应分析, 结果显示(见图5), 当层级一致时, 权力层级对于团队内权力争夺的主效应显著, F(1, 59) = 12.06, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.08, 权力不平等组的团队使用“一票决定权”的次数(M = 2.13, SD = 1.41)显著低于权力平等组(M = 3.37, SD = 1.59); 当层级不一致时, 权力层级对于权力争夺的主效应不显著F(1, 59) = 0.03, ns, 权力不平等组的团队在使用“一票决定权”的次数(M = 3.94, SD = 1.18)上与权力平等组(M = 3.31, SD = 1.78)没有显著差异。因此, 层级一致性也调节了权力层级与权力争夺的关系, 假设2得到了支持。

图5

在假设3中我们提出权力争夺中介了权力层级与层级一致性的交互与团队绩效的关系, 我们用多层回归的方法对权力争夺的中介作用进行检验。我们根据Muller, Judd和Yzerbyt (2005)的建议来检验这个被中介的调节模型。表6中的模型3 (M3)显示权力层级与层级一致性的交互对团队绩效的作用显著(b = 0.94, p < 0.05, t = 2.08); 但在权力争夺进入模型后(M4), 权力层级与层级一致性的交互对团队绩效的作用不再显著(b = 0.04, ns, t = 0.12), 而权力争夺对团队绩效的作用是显著的(b = -0.46, p < 0.01, t = -9.46)。

表6 多层回归分析结果

| 变量 | 团队绩效 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M 1 | M 2 | M 3 | M 4 | |

| 控制变量 | ||||

| 平均年龄 | -0.10 | -0.08 | -0.11 | -0.06 |

| 主效应 | ||||

| 权力层级 | 0.38 | -0.11 | 0.24 | |

| 层级一致性 | 0.74** | 0.27 | 0.31 | |

| 调节效应 | ||||

| 权力层级×层级一致性 | 0.94* | 0.04 | ||

| 中介效应 | ||||

| 权力争夺 | -0.46** | |||

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.71 |

| F | 1.47 | 4.90** | 4.97** | 27.83** |

| ΔR2 | 0.02 | 0.17** | 0.06** | 0.45** |

注:n = 64, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; 因变量为标准化后的团队绩效, 各模型中的回归系数均为非标准化的回归系数。

我们进一步用Preacher, Rucker和Hayes (2007)建议的Bootstrap方法对被中介的调节效应进行检验。我们将Bootstrap抽样的次数设定为20000次, 结果显示(见表7), 当层级不一致时, 权力层级对团队绩效的间接效应不显著(95%的置信区间包含零); 而当层级一致时, 权力层级对团队绩效的间接效应显著(95%的置信区间不包含零)。综合方差分析、回归分析和Bootstrap分析的结果, 我们所提的假设3得到了部分支持。

表7 被中介的调节效应分析结果

| 层级一致性 | 间接效应 | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| 层级不一致 | -0.35 | -0.91 | 0.14 |

| 层级一致 | 0.56 | 0.11 | 1.10 |

注:Bootstrap抽样次数为20000, 置信区间的置信度为95%。

研究2再次重复了研究1的结果, 发现层级一致性可以调节权力层级与团队绩效的关系; 但略有不同的是, 我们在研究2发现当层级一致时权力层级可以正向促进团队绩效, 而层级不一致时权力层级与团队绩效没有显著的关系; 而在研究1我们发现当层级一致时权力层级对团队绩效的效应为正但不显著, 而层级不一致时权力层级会削弱团队绩效。其次, 研究2检验了我们未在研究1中检验过的假设2和假设3, 结果发现层级一致性调节了权力层级与权力争夺的关系, 且权力争夺在权力层级与层级一致性交互和团队绩效关系中起到了中介作用, 所以假设3得到了支持。

4 研究3:权力层级与团队绩效的关系——层级一致性的调节作用的再次验证

研究1和研究2采用的样本都是学生样本, 虽然类似的学生样本已经被广泛应用于团队水平的层级研究中(e.g., Hays & Bendersky, 2015; Jung, Vissa, & Pich, 2017), 但是课程团队与工作团队依然存在差异, 这一定程度上影响了本研究的生态效度。为此, 我们将增加一个以高管团队为样本的现场研究来应对这一问题。

4.1 样本

研究3采用互联网行业新三板挂牌公司高管团队(TMT)的数据来验证我们的假设。研究3之所以采用这个样本主要出于以下几方面的原因:首先, 上市公司高管团队是研究团队权力和地位层级的合适样本(He & Huang, 2011; Greve, & Mitsuhashi, 2007)。其次, 互联网行业的企业组织扁平化的程度较高(Chen, He, & Chen, 2018), 层级不一致的现象在这一行业中可能更为普遍。再次, 新三板挂牌公司每年需根据全国中小企业股份转让系统的要求公开经过会计事务所审计的经营数据以及董事会和高管情况, 从而为我们的研究提供了较为客观的指标。最后, 新创企业的高管团队对于企业有较强的控制力, 对于企业经营绩效有着显著的影响(e.g., Busenitz, Plummer, Klotz, Shahzad, & Rhoads, 2014; Harper, 2008), 新三板挂牌的公司以新创企业为主, 因此为我们检验高管团队内的权力结构和层级一致性程度对于组织绩效的影响提供了有利条件。

由于新三板2013年底才开始面向全国接受企业挂牌申请, 所以目前可以获得的企业数据范围只有2013年至2017年。根据以往研究的建议, 高管团队的研究中, 样本团队应至少包含三位成员(e.g., Jackson et al., 1991), 因此我们剔除了高管团队成员低于3人的公司。此外, 一些公司在某些年份中由于摘牌等原因, 经营数据或高管成员数据缺失, 数据缺失年份的公司数据被剔除。经过以上步骤进行筛选后, 研究3最终的样本为169家挂牌企业的2013至2016年的共203个观测值3(3 组织绩效数据延后一年, 即包括2014年至2017年的公司净资产收益率数据。)。在这一样本中平均的年营业收入为33500万元(SD = 290000万元), 平均员工数量为139.44人(SD = 150.00), 高管团队平均成员人数为4.14人(SD = 1.34), 公司平均成立年限为4.14年(SD = 1.52)。

4.2 测量

权力层级。首先, 许多研究指出股权的多少很大程度上反映了公司高管的权力水平(e.g., Daily, & Johnson, 1997; Haynes, & Hillman, 2010), 因此研究3用TMT团队成员在公司中所持有的股份比例来衡量每个TMT成员的权力水平。与以往的研究(e.g., Cantimur et al., 2016; Halevy et al., 2012)以及研究1一致, 研究3采用TMT成员间权力的标准差作为计算权力层级的指标。

层级一致性。首先, 以往研究(He & Huang, 2011; Greve, & Mitsuhashi, 2007)指出企业高管在公司任职时间的长短反映了其在公司中的地位高低, 因此研究3用TMT成员在公司中的任职时长来衡量其地位, 任职时间越长, 其地位越高。其次, 我们将TMT团队成员的任职时长(地位)和股权比例(权力)都进行标准化, 然后与研究1计算层级一致性的方法一致, 先计算出每个成员标准化后的任职时长与标准化后的股权比例之差的绝对值, 并对该绝对值进行组内平均, 接着对绝对值取负数即计算出层级一致性。

公司绩效。净资产收益率(ROE)反映了公司回报股东投资的能力, 是衡量公司经营成功与否的重要指标之一(Hitt, Ireland, & Stadter, 1982), 且以往许多上市公司相关研究采用该指标来衡量公司绩效(e.g., Chadwick, Super, & Kwon, 2015; Peng, 2010; Zhao, & Murrell, 2016), 因此研究3采用净资产收益率来衡量公司绩效。与以往的上市公司二手数据研究相一致(e.g., He & Huang, 2011; Zhao, & Murrell, 2016), 我们采用比自变量延后一期(一年)的净资产收益率作为因变量。

控制变量。首先, 团队规模可能对团队绩效产生显著影响(Lepine et al., 2008), 因此在研究3对团队规模进行了控制。其次, 高管团队多样性对于组织绩效可能会产生影响(e.g., Boone & Hendriks, 2009; Campbell & Mínguez-Vera, 2008), 因此我们在研究3中控制了TMT团队的性别多样性以及教育水平多样性。再次, 许多研究指出时间因素会对团队过程和结果产生重要影响(e.g., Koopmann, Lanaj, Wang, Zhou, & Shi, 2016; Sieweke & Zhao, 2015), 因此我们在研究3中控制了团队平均任期4(4 团队平均任期的操作化定义为团队成员任期的均值。)。最后, 由于研究3的样本是包含了多个时间段(年份)的面板数据, 因此我们与以往面板数据研究一致(e.g., He & Huang, 2011; Sieweke & Zhao, 2015), 控制了观测值所在的数据年份。

4.3 结果

表8显示了各个变量的描述性统计以及相关分析结果, 从中可以看到, 与我们的预测一致, 权力层级与公司绩效(净资产收益率)并没有显著的相关性。由于研究3的数据包含了同一个样本不同时间点的观测值, 即为面板数据; 此时为了排除样本不随时间变化的特质的影响, 面板数据研究通常采用固定效应模型(fixed effect model)来进行数据分析(e.g., Campbell & Mínguez-Vera, 2008; Zhao, & Murrell, 2016), 因此我们也采用该方法来验证假设。

表8 变量均值、标准差和相关系数

| 变量 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 TMT团队规模 | 4.14 | 1.34 | - | |||||

| 2 性别多样性 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.16* | - | ||||

| 3 平均任期 | 3.45 | 1.94 | 0.00 | -0.11 | - | |||

| 4 教育水平多样性 | 0.59 | 0.35 | -0.04 | -0.13 | -0.10 | - | ||

| 5 权力层级 | 16.19 | 10.79 | -0.30** | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.10 | - | |

| 6 层级一致性 | -0.64 | 0.36 | -0.29** | 0.05 | -0.04 | -0.04 | 0.21** | - |

| 7 净资产收益率 | -0.21 | 2.24 | -0.11 | -0.12 | -0.03 | 0.13 | -0.00 | 0.05 |

注:n = 203. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01。表示数据年份的虚拟变量未列入。

在进行回归分析前, 为了削弱多重共线性的可能影响, 我们对所有预测变量进行了中心化处理。在假设1中我们提出权力层级与团队绩效的关系受到层级一致性的调节; 从固定效应模型回归分析的结果看(见表9), 在模型3(M3)中, 权力层级与层级一致性的交互对团队绩效的作用显著(b = 0.21, p < 0.05, t = 2.36)。

表9 固定效应模型回归分析结果

| 变量 | 公司绩效(净资产收益率) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M 1 | M 2 | M 3 | |

| 控制变量 | |||

| 数据年份 | 已控制 | 已控制 | 已控制 |

| TMT团队规模 | -0.24 | -0.29 | -0.15 |

| 性别多样性 | -2.64 | -2.06 | -3.27 |

| 平均任期 | -1.43** | -1.22* | -1.26* |

| 教育水平多样性 | 2.07 | 2.12 | 1.63 |

| 主效应 | |||

| 权力层级 | -0.12* | -0.08 | |

| 层级一致性 | 0.43 | 1.86 | |

| 调节效应 | |||

| 权力层级 × 层级一致性 | 0.21* | ||

| R2 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.58 |

| F | 1.76 | 2.31* | 2.99* |

注:n = 203. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, 各模型中的回归系数均为非标准化的回归系数。

我们对不同层级一致性水平下的权力层级与公司绩效关系进行了绘图, 见图6。简单效应分析的结果显示, 当层级一致性由低到高时, 代表权力层级与团队绩效关系的直线从斜率为负且显著(k = -0.16, p < 0.01), 变为斜率为正, 但是不显著(k = 0.004, ns)。说明层级不一致时, 权力层级与团队绩效负相关, 而当层级一致时, 权力层级与团队绩效的关系不显著。综合回归分析和简单效应分析的结果, 假设1得到了部分支持。

图6

4.4 数据稳健性检验

最后, 研究3通过不同的层级操作化指标对以上结果进行稳健性检验, 我们分别采用变异系数和中心化这两个指标来进行稳定性检验(e.g., Hays & Bendersky, 2015; Huang & Cummings, 2011)。首先,保持所有控制变量不变的前提下, 用团队成员权力的变异系数作为权力层级的操作化指标加入回归模型中; 结果显示, 权力层级与层级一致性的交互对公司绩效依然具有显著的正向作用(b = 4.84, p < 0.01, t = 3.05)。其次, 当采用中心化作为权力层级的操作化指标时, 权力层级与层级一致性的交互依然与公司绩效显著正相关(b = 13.63, p < 0.01, t = 3.13)。以上分析结果说明研究3的发现具有较强的稳健性。

研究3以新三板挂牌企业TMT团队为样本重复检验了本研究的假设1。结果发现层级一致性调节了权力层级与公司绩效的关系, 当层级一致性程度低时权力层级与公司绩效负相关, 而当层级一致性程度高时权力层级对公司绩效没有显著的影响; 因此假设1得到了部分支持。研究3通过以TMT团队为样本的现场研究弥补了研究1和研究2采用学生样本的不足, 增强了本研究的生态效度。

5 讨论

本研究结合问卷调查、实验、二手数据三种方法探索了层级一致性对于权力层级与团队绩效关系的调节作用, 以及权力争夺在权力层级和层级一致性的交互与团队绩效关系中的中介作用。研究结果部分地支持层级一致性调节了权力层级与团队绩效的关系, 以及权力层级与层级一致性的交互通过的权力争夺的中介从而影响团队绩效。

5.1 理论贡献

对于权力层级与团队绩效的关系, 现有的研究较为明显地分裂成了对立的两派, 强调权力层级积极作用的功能主义(e.g., Halevy et al., 2012; Ronay et al., 2012)与强调权力层级消极作用的功能障碍主义(e.g., Bloom, 1999; Huang & Cummings, 2011)都具有一定的理论基础和实证支持。现有的研究大多都默认了地位层级与权力层级是高度一致的, 而忽略了层级不一致可能造成的影响。本研究发现层级一致性调节了权力层级与团队绩效的关系, 并指出层级一致性影响了权力层级合法性的感知, 层级不一致削弱了权力层级的合法性, 而层级一致则可以加强权力层级的合法性, 从而对权力层级与权力争夺以及团队绩效的关系产生了影响。因此我们的研究有利于化解功能主义与功能障碍主义的分歧与对立, 功能主义所宣扬的权力层级积极作用需要在地位层级与之相一致时才能起效, 而地位层级与权力层级不一致时, 权力层级会由于缺乏合法性发挥消极作用。

其次, 我们的研究也拓展了权力层级合法性的研究。以往权力层级合法性的研究大都认为权力层级合法性来源于权力使用中的过程公平, 即权力层级是否合法取决于拥有权力者如何使用权力(e.g., Tyler, 2006; van Dijke, De Cremer, & Mayer, 2010)。而地位层级合法性的研究则提供了另一种视角, Ridgeway和Berger (1986)提出团队成员间绩效期望的差异越大, 地位层级的合法性越强, 且绩效期望的差异来源于团队成员个体特征的差异。也就是说地位层级的合法性可以来自于其是如何被构建的, 而并不是由其使用方式所单独决定。我们的研究进一步延伸了这一种观点, 提出地位层级与权力层级的一致性会影响权力层级的合法性。但由于我们的研究并没有直接测量权力层级的合法性, 因此未来的研究可以用直接测量的方式更加准确地检验我们的观点。

此外, 本研究还有助于推进层级一致性的研究。在Magee和Galinsky (2008)从理论上区分权力和地位并提出两者可能的不一致后, 个体水平的权力和地位不一致的研究开始涌现, 并取得了许多成果(e.g., Anicich et al., 2016; Blader & Chen, 2012; Fast et al., 2012)。但目前层级一致性的研究几乎都集中于个体水平。尽管有个别研究从双边关系的角度探讨了层级一致性对于双边关系的影响(i.e., Ma et al., 2013), 但目前层级一致性的研究还未从比个体和双边关系更复杂的群体或团队层面来考虑层级一致性可能的影响。另一方面, 在团队水平的层级研究中, 只有少数理论研究提及地位层级与权力层级的一致性的可能作用(Halevy et al., 2011), 时至今日绝大多数实证研究依然忽略了层级一致性的影响。本研究首次将层级一致性引入到团队水平的层级研究中, 并验证了层级一致性对权力层级与团队绩效关系的影响, 从而有利于推动层级一致性相关研究的发展。

5.2 管理启示

在当代的组织中, 团队逐渐成为组织的基本组成单元(Edmondson, 2002; Nohria & Garcia-Pont, 1991); 但应该采用何种结构来组织团队依然困扰着企业实践(Bunderson & Boumgarden, 2010)。按照层级功能主义的观点, 具有明确权力差异的层级式结构更加有利于团队运行; 但按照层级功能障碍主义的观点, 权力平等的层级结构才是更有利的。本研究发现团队内的权力层级是否有利于团队绩效取决于层级一致性。当层级一致时权力层级有利于团队绩效, 而当层级不一致时权力层级不利于团队绩效。所以对于管理者而言, 确保团队内地位层级与权力层级的一致是至关重要的。

5.3 研究不足

本研究也存在一些不足之处。首先, 本研究没有在多种情境和多种团队任务下重复检验我们的理论。例如, 我们并未探索是否在高度创新性任务下我们的理论依然成立, 而有研究认为权力层级会抑制团队内新颖观点的形成(e.g., Yuan & Zhou, 2015), 因此, 可能即使在层级一致的前提下, 权力层级依然是对创新有害的。其次, 我们在研究1和研究3中发现, 团队成员的权力和地位的相关度较高, 这一定程度上从侧面支持了以往研究默认的关于权力和地位一致较为常见的观点(e.g., Magee & Galinsky, 2008); 但我们在观测数据中也确实发现存在以往研究指出的权力与地位不一致现象(e.g., Blader & Chen, 2014),甚至一些团队中成员的权力和地位是负相关的。至于是测量、取样还是其他情境因素导致了团队成员的权力和地位相关度整体上偏高,在未来研究中值得进一步探讨。

6 结论

本研究探索了层级一致性对权力层级与团队绩效关系的调节作用。通过分别采用问卷调查、实验和二手数据研究方法的三个子研究发现, 当层级一致时, 权力层级有利于团队绩效, 而层级不一致时, 权力层级不利于团队绩效; 并且权力争夺在权力层级和层级一致性的交互与团队绩效的关系中起中介作用。

参考文献

Inequity in social exchange. In B. Leonard (Ed. ), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology

(Volume

The functions and dysfunctions of hierarchy

DOI:10.1016/j.riob.2010.08.002

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Functionalist accounts of hierarchy, longstanding in the social sciences, have gained recent prominence in studies of leadership, power, and status. This chapter takes a critical look at a core implication of the functionalist perspective – namely, that steeper hierarchies help groups and organizations perform better than do flatter structures. We review previous research relevant to this question, ranging from studies of communication structures in small groups to studies of compensation systems in large corporations. This review finds that in contrast to strong functionalist assertions, the effects of steeper hierarchies are highly mixed. Sometimes steeper hierarchies benefit groups and sometimes they harm groups. We thus propose five conditions that moderate the effects of hierarchy steepness: (1) the kinds of tasks on which the group is working; (2) whether the right individuals have been selected as leaders; (3) how the possession of power modifies leaders’ psychology; (4) whether the hierarchy facilitates or hampers intra-group coordination; and (5) whether the hierarchy affects group members’ motivation in positive or deleterious ways.

When the bases of social hierarchy collide: Power without status drives interpersonal conflict: Power without status drives interpersonal conflict

Hierarchical cultural values predict success and mortality in high-stakes teams

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1408800112

URL

PMID:25605883

[本文引用: 1]

Functional accounts of hierarchy propose that hierarchy increases group coordination and reduces conflict. In contrast, dysfunctional accounts claim that hierarchy impairs performance by preventing low-ranking team members from voicing their potentially valuable perspectives and insights. The current research presents evidence for both the functional and dysfunctional accounts of hierarchy within the same dataset. Specifically, we offer empirical evidence that hierarchical cultural values affect the outcomes of teams in high-stakes environments through group processes. Experimental data from a sample of expert mountain climbers from 27 countries confirmed that climbers expect that a hierarchical culture leads to improved team coordination among climbing teams, but impaired psychological safety and information sharing compared with an egalitarian culture. An archival analysis of 30,625 Himalayan mountain climbers from 56 countries on 5,104 expeditions found that hierarchy both elevated and killed in the Himalayas: Expeditions from more hierarchical countries had more climbers reach the summit, but also more climbers die along the way. Importantly, we established the role of group processes by showing that these effects occurred only for group, but not solo, expeditions. These findings were robust to controlling for environmental factors, risk preferences, expedition-level characteristics, country-level characteristics, and other cultural values. Overall, this research demonstrates that endorsing cultural values related to hierarchy can simultaneously improve and undermine group performance.

Team familiarity and productivity in cardiac surgery operations: The effect of dispersion, bottlenecks, and task complexity

Centralized sanctioning and legitimate authority promote cooperation in humans

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1105456108 URL [本文引用: 1]

Status conflict in groups

DOI:10.1287/orsc.1110.0734 URL [本文引用: 3]

Status characteristics and social interaction

DOI:10.2307/2093465

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This paper discusses the small groups literature on status organizing processes in decision-making groups whose members differ in external status. This literature demonstrates that status characteristics, such as age, sex, and race determine the distribution of participation, influence, and prestige among members of such groups. This effect is independent of any prior cultural belief in the relevance of the status characteristic to the task. To explain this result, we assume that status determines evaluations of, and performance-expectations for group members and hence the distribution of participation, influence, and prestige. We stipulate conditions sufficient to produce this effect. Further, to explain the fact that the effect is independent of prior cultural belief, we assume that a status characteristic becomes relevant in all situations except when it is culturally known to be irrelevant. Direct experiment supports each assumption in this explanation independently of the others. Subsequent work devoted to refining and extending the theory finds among other things that, given two equally relevant status characteristics, individuals combine all inconsistent status information rather than reduce its inconsistency. If this result survives further experiment it extends the theory on a straightforward basis to multi-characteristic status situations.

Looking out from the top: Differential effects of status and power on perspective taking

DOI:10.1177/0146167216636628 URL [本文引用: 4]

Differentiating the effects of status and power: A justice perspective

DOI:10.1037/a0026651

URL

PMID:22229456

[本文引用: 3]

Few empirical efforts have been devoted to differentiating status and power, and thus significant questions remain about differences in how status and power impact social encounters. We conducted 5 studies to address this gap. In particular, these studies tested the prediction that status and power would have opposing effects on justice enacted toward others. In the first 3 studies, we directly compared the effects of status and power on people's enactment of distributive (Study 1) and procedural (Studies 2 and 3) justice. In the last 2 studies, we orthogonally manipulated status and power and examined their main and interactive effects on people's enactment of distributive (Study 4) and procedural (Study 5) justice. As predicted, all 5 studies showed consistent evidence that status is positively associated with justice toward others, while power is negatively associated with justice toward others. The effects of power are moderated, however, by an individual's other orientation (Studies 2, 3, 4, and 5), and the effects of status are moderated by an individual's dispositional concern about status (Study 5). Furthermore, Studies 4 and 5 also demonstrated that status and power interact, such that the positive effect of status on justice emerges when power is low and not when power is high, providing further evidence for differential effects between power and status. Theoretical implications for the literatures on status, power, and distributive/procedural justice are discussed.

What’s in a name? Status, power, and other forms of social hierarchy

DOI:10.1007/978-1-4939-0867-7_4

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Despite a long history in social sciences such as anthropology and sociology, status has not received its deserved status in psychology and related domains such as management. This chapter attempts to bring greater clarity to the conceptualization of status and to highlight its distinctions from related bases of social hierarchy, such as power, dominance, and influence. To accomplish these goals, we first review current conceptual thinking on status and other related bases of social hierarchy. We then present a review of recent empirical evidence that supports differentiation among these bases of social hierarchy, focusing primarily on empirical work that differentiates status and power. We then propose an integrative framework that organizes the many related, yet distinct constructs that describe social hierarchy. Throughout, we are attentive to the fundamental question of why distinguishing status from these related aspects of social hierarchy matters oth for research and for a better understanding of social life.

The performance effects of pay dispersion on individuals and organizations

DOI:10.2307/256872

URL

[本文引用: 4]

Pay distribution research is relatively scarce in the compensation literature, yet pay distributions are viewed as critically important by organizational decision makers. This study is a direct test of the relationship between one form of pay distribution--pay dispersion--and performance conducted in a field setting where individual and organizational performance could be reliably observed and measured. Findings suggest more compressed pay dispersions are positively related to multiple measures of individual and organizational performance.

Top management team diversity and firm performance: Moderators of functional- background and locus-of-control diversity

DOI:10.1287/mnsc.1080.0899

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Past research on the relationship between top management team (TMT) compositional diversity and organizational performance has paid insufficient attention to the nature of TMT team processes in interaction with TMT diversity. We fill this gap by studying how three team mechanisms (collaborative behavior, accurate information exchange, and decision-making decentralization) moderate the impact of TMT diversity on financial performance of 33 information technology firms. We focus on two fundamentally different forms of TMT diversity: functional-background (FB) and locus-of-control (LOC). We argue that the former has the potential to enhance decision quality and organizational performance, whereas the latter might trigger relational conflict, and is, therefore, potentially detrimental to firm effectiveness. The ultimate aim of our study is to analyze which team processes help to transform distributed FB knowledge into high-quality decisions and organizational effectiveness, and which help avoid the potential detrimental effects of LOC diversity. We find that a TMTs collaborative behavior and information exchange are necessary conditions to unleash the performance benefits of FB diversity, but do not interact with LOC diversity. In addition, decentralized decision making spurs the effectiveness of functionally diverse teams, while at the same time reinforces the negative consequences of LOC diversity on firm performance.

Translation and content analysis of oral and written material

Structure and learning in self-managed teams: Why “bureaucratic” teams can be better learners

DOI:10.1287/orsc.1090.0483

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This paper considers the effect of team structure on a team's engagement in learning and continuous improvement. We begin by noting the uncertain conceptual status of the structure concept in the small groups literature and propose a conceptualization of team structure that is grounded in the long tradition of work on formal structure in the sociology and organization theory literatures. We then consider the thesis that, at least in self-managed teams dealing with stable tasks, greater team structure---i.e., higher levels of specialization, formalization, and hierarchy---can promote learning by encouraging information sharing, reducing conflict frequency, and fostering a climate of psychological safety; that is, we examine a mediated model in which the effect of structure on learning and improvement in teams is mediated by psychological safety, information sharing, and conflict frequency. This model was largely supported in a study of self-managed production teams in a Fortune 100 high-technology firm, although the observed pattern of mediation was more complex than anticipated. Higher structure was also associated with actual productivity improvements in a subsample of these teams. The theory and results of this study advance our understanding of team learning and underscore the importance of team structure in research on team processes and performance.

Different views of hierarchy and why they matter: Hierarchy as inequality or as cascading influence

DOI:10.5465/amj.2014.0601 URL [本文引用: 1]

Power, status, and learning in organizations

DOI:10.1287/orsc.1100.0590

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This paper reviews the scholarly literature on the effects of social hierarchy---differences in power and status among organizational actors---on collective learning in organizations and groups. We begin with the observation that theories of organization and group learning have tended to adopt a rational system model, a model that emphasizes goal-directed and cooperative interactions between and among actors who may differ in knowledge and expertise but are undifferentiated with respect to power and status. Our review of the theoretical and empirical literatures on power, status, and learning suggests that social hierarchy can complicate a rational system model of collective learning by disrupting three critical learning-related processes: anchoring on shared goals, risk taking and experimentation, and knowledge sharing. We also find evidence to suggest that the stifling effects of power and status differences on collective learning can be mitigated when advantaged actors are collectively oriented. Indeed, our review suggests that higher-ranking actors who use their power and status in more ocialized ways can play critical roles in stimulating collective learning behavior. We conclude by articulating several promising directions for future research that were suggested by our review.

Entrepreneurship research (1985-2009) and the emergence of opportunities

Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance

DOI:10.1007/s10551-007-9630-y

URL

[本文引用: 3]

The monitoring role performed by the board of directors is an important corporate governance control mechanism, especially in countries where external mechanisms are less well developed. The gender composition of the board can affect the quality of this monitoring role and thus the financial performance of the firm. This is part of the "business case" for female participation on boards, though arguments may also be framed in terms of ethical considerations. While the issue of board gender diversity has attracted growing research interest in recent years, most empirical results are based on U.S. data. This article adds to a growing number of non-U.S. studies by investigating the link between the gender diversity of the board and firm financial performance in Spain, a country which historically has had minimal female participation in the workforce, but which has now introduced legislation to improve equality of opportunities. We investigate the topic using panel data analysis and find that gender diversity - as measured by the percentage of women on the board and by the Blau and Shannon indices - has a positive effect on firm value and that the opposite causal relationship is not significant. Our study suggests that investors in Spain do not penalise firms which increase their female board membership and that greater gender diversity may generate economic gains.

When and why hierarchy steepness is related to team performance

DOI:10.1080/1359432X.2016.1148030

URL

[本文引用: 3]

This study develops and tests a contingency theory on the functions of status hierarchy steepness in teams. Findings from a field study among 438 employees working in 72 work teams across diverse business settings demonstrate that task complexity moderates the relationships between status hierarchy steepness, different types of team conflict, and team performance. Steeper status hierarchies were negatively related to both process and task conflict, and hence increased team performance in teams working on tasks with lower complexity but did not yield such clear conflict and performance effects in teams working on more complex tasks. By showing that various levels of task complexity determine whether status hierarchy steepness has a conflict-regulating function that drives team performance, this research generates valuable insights about the context dependency of team responses to status hierarchy steepness.

Resource orchestration in practice: CEO emphasis on SHRM, commitment-based HR systems, and firm performance

DOI:10.1002/smj.2217

URL

[本文引用: 1]

In order to be effective, managers at all levels of the firm must engage in resource management activities, and these efforts are synchronized and orchestrated by top management. Using a specific type of strategic resource, commitment-based human resource systems, we examine the effect of CEO resource orchestration in a multi-industry sample of 190 Korean firms. Our results demonstrate that CEO emphasis on strategic HRM is a significant antecedent to commitment-based HR systems. Furthermore, our results also suggest that CEO emphasis on strategic HRM has its primary effects on firm performance through commitment-based HR systems. This finding underscores the importance of middle managers in operationalizing top management's strategic emphasis, lending empirical support to a fundamental tenet of resource orchestration arguments . Copyright 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

What drives internet industrial competitiveness in china the evolvement of cultivation factors index

The rapid and continuous growth of the Internet industry is highly important to China’s economy. Based on Porter’s diamond model and using data from 2002 to 2016, we construct a cultivation factor index of China’s Internet industrial competitiveness and its four composite indicators. We study the evolvement of the indexes over 15 years and analyze events that were key to the growth of cultivation factors of China’s Internet industrial competitiveness. The findings are as follows: (1) the cultivation factor index of Internet industrial competitiveness grows fast in waves, with alternating periods of steady growth and leap growth; (2) innovation in technology application, not technology itself, promotes the rapid increase of index; and (3) the influence of environmental opportunities and governments polices is demonstrated in evolvement of the index.

A process study of entrepreneurial team formation: The case of a research- based spin-off

DOI:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00113-1

URL

[本文引用: 2]

This paper describes how a team of entrepreneurs is formed in a high-tech start-up, how the team copes with crisis situations during the start-up phase, and how both the team as a whole and the team members individually learn from these crises. The progress of a high-tech university spin-off has been followed up from the idea phase until the post-start-up phase. Adopting a prospective, qualitative approach, the basic argument of this paper is that shocks in the founding team and the position of its champion co-evolve with shocks in the development of the business.

Sources of CEO power and firm financial performance: A longitudinal assessment

DOI:10.1016/s0149-2063(97)90039-8

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The chief executive officer (CEO) is generally regarded as the most powerful organizational member. Attributions regarding the potential effect of a strong CEO on firm financial performance are common in both the academic literature and popular press. The oft-made assumption is that a powerful CEO will impact firm performance. The anticipated direction of this influence, however, has not been uniformly established. Moreover, we are not aware of any direct empirical assessment of the relationship between CEO power and firm financial performance. We are also intrigued by the potential for reciprocal effects—firm performance impacts the level of CEO’s power. Our review of the literature demonstrates no empirical attention to this possibility. This study relies on a four-wave panel design to assess the nature of the relationship between CEO power and firm performance. Results of LISREL analysis demonstrate that aspects of CEO power and financial performance are, in fact, interrelated. Performance was found to be both an antecedent condition and outcome of CEO power.

Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: A meta-analysis

DOI:10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.741

URL

PMID:12940412

[本文引用: 1]

This study provides a meta-analysis of research on the associations between relationship conflict, task conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction. Consistent with past theorizing, results revealed strong and negative correlations between relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction. In contrast to what has been suggested in both academic research and introductory textbooks, however, results also revealed strong and negative (instead of the predicted positive) correlations between task conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction. As predicted, conflict had stronger negative relations with team performance in highly complex (decision making, project, mixed) than in less complex (production) tasks. Finally, task conflict was less negatively related to team performance when task conflict and relationship conflict were weakly, rather than strongly, correlated.

A theory of cooperation and competition

DOI:10.1177/001872674900200204 URL [本文引用: 2]

Cooperation, competition, and conflict

The local and variegated nature of learning in organizations: A group-level perspective

DOI:10.1287/orsc.13.2.128.530

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This paper considers the role of team learning in organizational learning. I propose that a group-level perspective provides new insight into how organizational learning is impeded, hindering effective change in response to external pressures. In contrast to previous theoretical perspectives, I suggest that organizational learning is local, interpersonal, and variegated. I present data from an exploratory study of learning processes in 12 organizational teams engaged in activities ranging from strategic planning to hands-on manufacturing of products. These qualitative data are used to investigate two components of the collective learning process—reflection to gain insight and action to produce change—and to explore how teams allow an organization to engage in both radical and incremental learning, as needed in a changing and competitive environment. I find that team members' perceptions of power and interpersonal risk affect the quality of team reflection, which has implications for their team's and their organization's ability to change.

Politics of strategic decision making in high-velocity environments: Toward a midrange theory

The destructive nature of power without status

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.07.013

URL

[本文引用: 3]

78 Most research has studied power and status in isolation. 78 We explored how power and status interact. 78 We orthogonally crossed power and status and assessed behavior. 78 Power without status led to demeaning behavior toward others.

The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations

DOI:10.1037/0033-295X.99.4.689 URL [本文引用: 1]

Interpersonal stratification: Status, power, and subordination

DOI:10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy002026

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This chapter aims to illuminate the interpersonal dynamics of stratification, first defining it and related terms such as hierarchy, status, power, subordination, and oppression. Current research typically promotes either the advantages or disadvantages, respectively, of being at the top or the bottom of the social heap, revealing short and long term effects of hierarchy. Overall, however, the social psychology of stratification demonstrates both personal gains and losses to individuals, no matter what their hierarchical context.

Power in teams: Effects of team power structures on team conflict and team outcomes

The bigger they are, the harder they fall: Linking team power, team conflict, and performance

DOI:10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.03.005

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Across two field studies, we investigate the impact of team power on team conflict and performance. Team power is based on the control of resources that enables a team to influence others in the company. We find across both studies that low-power teams outperform high-power teams. In both studies, higher levels of process conflict present in high-power teams explain this effect fully. In our second study, we show that team interpersonal power congruence (i.e., the degree to which team members self-views of their individual power within the team align with the perceptions of their other team members) ameliorates the relationship between team power and process conflict, such that when team interpersonal power congruence is high, high-power teams are less likely to experience performance-detracting process conflict.

Equality versus differentiation: The effects of power dispersion on group interaction

DOI:10.1037/a0020373

URL

PMID:20822207

[本文引用: 9]

Power is an inherent characteristic of social interaction, yet research has yet to fully explain what power and power dispersion may mean for conflict resolution in work groups. We found in a field study of 42 organizational work groups and a laboratory study of 40 negotiating dyads that the effects of power dispersion on conflict resolution are contingent on the level of interactants' power, thereby explaining contradictory theory and findings on power dispersion. We found that when members have low power, power dispersion is positively related to conflict resolution, but when members have high power, power dispersion is negatively related to conflict resolution (i.e., power equality is better). These findings can be explained by the mediating role of intragroup power struggles. Together, these findings suggest that power hierarchies function as a heuristic solution for conflict and contribute to adaptive social dynamics in groups with low, but not high, levels of power.

The dysfunctions of power in teams: A review and emergent conflict perspective

DOI:10.1016/j.riob.2017.10.005

URL

[本文引用: 2]

We review the new and growing body of work on power in teams and use this review to develop an emergent theory of how power impacts team outcomes. Our paper offers three primary contributions. First, our review highlights potentially incorrect assumptions that have arisen around the topic of power in teams and documents the areas and findings that appear most robust in explaining the effects of power on teams. Second, we contrast the findings of this review with what is known about the effects of power on individuals and highlight the directionally oppositional effects of power that emerge across different levels of analysis. Third, we integrate findings across levels of analysis into an emergent theory which explains why and when the benefits of power for individuals may paradoxically explain the potentially negative effects of power on team outcomes. We elaborate on how individual social comparisons within teams where at least one member has power increase intra-team power sensitivity, which we define as a state in which team members are excessively perceptive of, affected by, and responsive to resources. We theorize that when power-sensitized teams experience resource threats (either stemming from external threats or personal threats within the team), these threats will ignite internal power sensitivities and set into play performance-detracting intra-team power struggles. This conflict account of power in teams integrates and organizes past findings in this area to explain why and when power negatively affects team-level outcomes, and opens the door for future research to better understand why and when power may benefit team outcomes when power 檚 dark side for teams is removed.

Power and glory: Concentrated power in top management teams

Organizational preferences and their consequences

DOI:10.1002/9780470561119.socpsy002033

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract 1 What is An Organization? 2 Organizational Homogeneity 3 Organizational Hierarchy 4 Homogeneity and Hierarchy are Mutually Reinforcing 5 Performance Implications of Organizing Preferences 6 Summary

When hierarchy wins: Evidence from the national basketball association

DOI:10.1177/1948550611424225 URL [本文引用: 6]

A functional model of hierarchy: Why, how, and when vertical differentiation enhances group performance

DOI:10.1177/2041386610380991 URL [本文引用: 5]

Towards a theory of entrepreneurial teams

DOI:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.002

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This article examines the role of entrepreneurial teams in processes of entrepreneurial discovery. It addresses two main questions. The first investigates the implications of economic theory for the possibility of team entrepreneurship. Because leading economic theories focus almost exclusively upon individual decision-makers, we propose a broader notion of entrepreneurship that includes enterprising teams as well as individuals. We define entrepreneurship as a profit-seeking problem-solving process that takes place under conditions of structural uncertainty. The second question examines the conditions that are conducive to joint entrepreneurial action and the formation of entrepreneurial teams. We suggest that bounded structural uncertainty and perceived strong interdependence arising from common interest can jointly “prime” team entrepreneurship.

What's the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations

DOI:10.2307/20159363

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Research on organizational diversity, heterogeneity, and related concepts has proliferated in the past decade, but few consistent findings have emerged. We argue that the construct of diversity requires closer examination. We describe three distinctive types of diversity: separation, variety, and disparity. Failure to recognize the meaning, maximum shape, and assumptions underlying each type has held back theory development and yielded ambiguous research conclusions. We present guidelines for conceptualization, measurement, and theory testing, highlighting the special case of demographic diversity.

The effect of board capital and CEO power on strategic change

DOI:10.1002/smj.859

URL

[本文引用: 1]

We develop the construct of board capital, composed of the breadth and depth of directors 'human and social capital, and explore how board capital affects strategic change. Building upon resource dependence theory, we submit that board capital breadth leads to more strategic change, while board capital depth leads to less. We also recognize CEO power as a moderator of these relationships. Our hypotheses are tested using a random sample of firms on the S & P 500. We find support for the effect of board capital on strategic change, and partial support for the moderating effect of CEO power.

Fear and loving in social hierarchy: Sex differences in preferences for power versus status

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2013.08.007

URL

[本文引用: 2]

61Paper examines relative desirability of power and status.61Men desire power more than women do but women desire status more than men do.61Legitimacy affects desirability of status but not power.

Not all inequality is created equal: Effects of status versus power hierarchies on competition for upward mobility

DOI:10.1037/pspi0000017

URL

PMID:25822034

[本文引用: 7]

Abstract Although hierarchies are thought to be beneficial for groups, empirical evidence is mixed. We argue and find in 7 studies spanning methodologies and samples that different bases of hierarchical differentiation have distinct effects on lower ranking group members' disruptive competitive behavior because status hierarchies are seen as more mutable than are power hierarchies. Greater mutability means that more opportunity exists for upward mobility, which motivates individuals to compete in hopes of advancing their placement in the hierarchy. This research provides further evidence that different bases of hierarchy can have different effects on individuals and the groups of which they are a part and explicates a mechanism for those effects. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2015 APA, all rights reserved).

Power and legitimacy influence conformity

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2015.04.010

URL

[本文引用: 1]

61This research examines the interaction of power and legitimacy on conformity.61Legitimate power decreases conformity, consistent with prior research.61However, illegitimate power increases conformity.

Board informal hierarchy and firm financial performance: Exploring a tacit structure guiding boardroom interactions

DOI:10.5465/amj.2009.0824

URL

[本文引用: 4]

We consider boards as human groups in the uppermost echelon of corporations and examine how an informal hierarchy that tacitly forms among a firm's directors affects firm financial performance. This informal hierarchy is based on directors' deference for one another. We argue that the clarity of the informal hierarchy can help coordinate boardroom interactions and thereby improve the likelihood of the board's contributing productively to the firm's performance. We further identify a set of internal and external contingencies affecting the functioning of the informal hierarchy. Our analysis of seven-year panel data on 530 U.S. manufacturing firms provides support for our arguments.

Functional importance and company performance: Moderating effects of grand strategy and industry type

DOI:10.2307/2486299

URL

[本文引用: 1]

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2486299

When critical knowledge is most critical: Centralization in Knowledge- Intensive teams

DOI:10.1177/1046496411410073 URL [本文引用: 3]

Group members’ status and knowledge sharing: A motivational perspective

团队成员地位与知识分享行为:基于动机的视角

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2015.00545

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Knowledge sharing has long been recognized as an effective way of making full use of the information and knowledge owned by group members. Although there are still few studies in exploring the relationship between status and knowledge sharing, extant literature has demonstrated contradictory conclusions concerning the effect of status. From a motivational perspective, this study aimed to explore how status would influence group members’ knowledge sharing behavior under different circumstances. Specifically, we speculated that the effect of status on group members’ knowledge sharing behavior was contingent on status stability within groups. When the difference in status was stable, high-status members would demonstrate more knowledge sharing behavior than low-status members. However, when the status difference was unstable, the condition would be reversed. Furthermore, we posited that the extent to which a group member would be influenced by status might depend on his or her concern for status. We predicted that individual status, status stability, and concern for status would have a three-way interaction effect on group members’ knowledge sharing behavior. A 2 (Status: high vs. low) × 2 (Status stability: stable vs. unstable) between-group experiment was conducted to test our hypotheses. A total of 113 college students participated in the experiment and were directed to finish two tests on a computer program. Each participant had two simulated teammates. After the first round of test, “artificial” performance was fed back to each participant. In the second round, each participant was given 12 chances to share answers with his or her teammates. After the test, they were asked to fill out a questionnaire on the computer. In this study, we used performance rating to manipulate individual status in groups and manipulated status stability by changing the task type in the second round of test. Knowledge sharing behavior was measured by the times each participant agreed to share his or her answer. We used SPSS 17.0 to analyze our data. Most of our hypotheses were supported by the results. First, status stability would interact with individual status to have a significant effect on group members’ knowledge sharing behavior. F-test showed that in a high status stability condition, high-status members demonstrated more knowledge sharing behavior than low-status members did. However, in a low status stability condition, low-status members tended to share more knowledge with others than high-status members did. It was also revealed that high-status members were more likely to share their knowledge when the status difference was stable than when it was unstable condition. In addition, when the status difference was stable within group, individual’s concern for status would interact with one’s status to impact his or her knowledge sharing behavior, such that the more concern the low-status members had for their status, the less they would share their knowledge within the group. Overall, we discuss individual’s dual motives at different status levels as well as the relationship between group members’ status and knowledge sharing behavior. It contributes to the literature in the following ways. First, it optimizes ecological validity of group study and makes a contribution to explore the interaction process within group. Second, by introducing status stability as a contextual factor, we integrate contradictory theories and develop a more comprehensive understanding of the effect of status. What is more, we supplement the study of status by investigating status from a motivational perspective. The findings have practical implications for group knowledge management.

Some differences make a difference: Individual dissimilarity and group heterogeneity as correlates of recruitment, promotions, and turnover

DOI:10.1037/0021-9010.76.5.675

URL

[本文引用: 1]

ABSTRACT B. Schneider's (1987) attraction-selection-attrition model and J. Pfeffer's (1983) organization demography model were used to generate individual-level and group-level hypotheses relating interpersonal context to recruitment, promotion, and turnover patterns. Interpersonal context was operationalized as personal dissimilarity and group heterogeneity with respect to age, tenure, education level, curriculum, alma mater, military service, and career experiences. For 93 top management teams in bank holding companies examined over a 4-yr period, turnover rate was predicted by group heterogeneity. For individuals, turnover was predicted by dissimilarity to other group members, but promotion was not. Team heterogeneity was a relatively strong predictor of team turnover rates. Furthermore, reliance on internal recruitment predicted subsequent team homogeneity. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)

Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement

DOI:10.1037/0021-9010.67.2.219 URL [本文引用: 1]

New developments in social interdependence theory

DOI:10.3200/MONO.131.4.285-358

URL

PMID:17191373

[本文引用: 1]

Social interdependence theory is a classic example of the interaction of theory, research, and practice. The premise of the theory is the way that goals are structured determines how individuals interact, which in turn creates outcomes. Since its for mulation nearly 60 years ago, social interdependence theory has been modified, extended, and refined on the basis of the increasing knowledge about, and application of, the theory. Researchers have conducted over 750 research studies on the relative merits of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic efforts and the conditions under which each is appropriate. Social interdependence theory has been widely applied, especially in education and business. These applications have resulted in revisions of the theory and the generation of considerable new research. The authors critically analyze the new developments resulting from extensive research on, and wide-scale applications of, social interdependence theory.

How do entrepreneurial founding teams allocate task positions?

DOI:10.5465/amj.2014.0813

URL

[本文引用: 1]

How do founding team members allocate task positions when launching new ventures? Answering this question is important because prior work shows both that founding team members often have correlated expertise, thus making task position allocation problematic; and initial occupants of task positions exert a lingering effect on venture outcomes. We draw on status characteristics theory to derive predictions on how co-founders specific expertise cues and diffuse status cues drive initial task position allocation. We also examine the performance consequences of mismatches between the task position and position occupant. Qualitative fieldwork combined with a quasi-experimental simulation game and an experiment provides causal tests of the conceptual framework. We find that co-founders whose diffuse status cues of gender (male), ethnicity (white) or achievement (occupational prestige or academic honors) indicated general ability were typical occupants of higher ranked positions, such as CEO role, within the founding team. In addition, specific expertise cues that indicated relevant ability predicted task position allocation. Founding teams created more financially valuable ventures when task position occupants diffuse status cues were typical for the position; nonetheless position occupants with high diffuse status cues also appropriated more of the created value. Our results inform both entrepreneurship and status characteristics literature.

A reciprocal influence model of social power: Emerging principles and lines of inquiry

DOI:10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00003-2

URL

[本文引用: 1]

In the present chapter, we advance a reciprocal influence model of social power. Our model is rooted in evolutionist analyses of primate hierarchies, and notions that the capacity for subordinates to form alliances imposes important demands upon those in power, and that power heuristically reduces the likelihood of conflicts within groups. Guided by these assumptions, we posit a set of propositions regarding the reciprocal nature of power, and review recent supporting data. With respect to the acquisition of social power, we show that power is afforded to those individuals and strategic behaviors related to advancing the interests of the group. With respect to constraints upon power, we detail how group‐based representations (a fellow group member's reputation), communication (gossip), and self‐assessments (an individual's modest sense of power) constrain the actions of those in power according to how they advance group interests. Finally, with respect to the notion that power acts as a social interaction heuristic, we examine how social power is readily and accurately perceived by group members and gives priority to the emotions, goals, and actions of high‐power individuals in shaping interdependent action. We conclude with a discussion of recent studies of the subjective sense of power and class‐based ideologies.

Hierarchy and its discontents: Status disagreement leads to withdrawal of contribution and lower group performance

DOI:10.1287/orsc.2016.1058 URL [本文引用: 1]

Team Tenure and member performance: The roles of psychological safety climate and climate strength

DOI:10.5465/AMBPP.2014.74

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Current understanding of the effect of team tenure on team processes suggests that psychological safety climate and climate strength increase as team tenure increases. However, theoretical and empirical work contradicts this assumption. Specifically, team development theories suggest that teams encounter various interpersonal experiences throughout their tenure, making a linear relationship an unlikely description of team tenure relationship with psychological safety climate and climate strength. The primary purpose of this research is to develop and test theory that captures the complex way in which psychological safety climate and climate strength develop as a function of team tenure. We found that team tenure had a curvilinear relationship with psychological safety climate and climate strength. Shorter-tenured teams exhibited a negative relationship between team tenure and psychological safety climate and climate strength, whereas longer-tenured teams exhibited a positive relationship between team tenure and psychological safety climate and climate strength. Moreover, we considered whether the nonlinear effect of team tenure translates to affect member performance via psychological safety climate. We found that psychological safety climate was positively related to creative performance regardless of climate strength, whereas psychological safety climate was positively associated with job performance in strong climates but unassociated in weak climates.

Younger supervisors, older subordinates: An organizational-level study of age differences, emotions, and performance

DOI:10.1002/job.2129

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Younger employees are often promoted into supervisory positions in which they then manage older subordinates. Do companies benefit or suffer when supervisors and subordinates have inverse age differences? In this study, we examine how average age differences between younger supervisors and older subordinates are linked to the emotions that prevail in the workforce, and to company performance. We propose that the average age differences determine how frequently older subordinates and their coworkers experience negative emotions, and that these emotion frequency levels in turn relate to company performance. The indirect relationship between age differences and performance occurs only if subordinates express their feelings toward their supervisor, but the association is neutralized if emotions are suppressed. We find consistent evidence for this theoretical model in a study of 61 companies with multiple respondents.

Illegitimacy moderates the effects of power on approach

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02123.x

URL

PMID:18578845

[本文引用: 1]

ABSTRACT A wealth of research has found that power leads to behavioral approach and action. Four experiments demonstrate that this link between power and approach is broken when the power relationship is illegitimate. When power was primed to be legitimate or when power positions were assigned legitimately, the powerful demonstrated more approach than the powerless. However, when power was experienced as illegitimate, the powerless displayed as much approach as, or even more approach than, the powerful. This moderating effect of legitimacy occurred regardless of whether power and legitimacy were manipulated through experiential primes, semantic primes, or role manipulations. It held true for behavioral approach (Experiment 1) and two effects associated with it: the propensity to negotiate (Experiment 2) and risk preferences (Experiments 3 and 4). These findings demonstrate that how power is conceptualized, acquired, and wielded determines its psychological consequences and add insight into not only when but also why power leads to approach.

A meta-analysis of teamwork processes: Tests of a multidimensional model and relationships with team effectiveness criteria

DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2008.00114.x URL [本文引用: 2]

Status effects on teams

Power source mismatch and the effectiveness of interorganizational relations: The case of venture capital syndication

DOI:10.5465/amj.2010.0832 URL [本文引用: 2]

Social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status

DOI:10.5465/19416520802211628 URL [本文引用: 10]

Organizations as resource dilemmas: The effects of power balance on coalition formation in small groups

DOI:10.1006/obhd.1993.1021

URL

[本文引用: 2]

No abstract is available for this item.

Team effectiveness 1997-2007: A review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future

DOI:10.1177/0149206308316061

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract The authors review team research that has been conducted over the past 10 years. They discuss the nature of work teams in context and note the substantive differences underlying different types of teams. They then review representative studies that have appeared in the past decade in the context of an enhanced input-process-outcome framework that has evolved into an inputs-mediators-outcome time-sensitive approach. They note what has been learned along the way and identify fruitful directions for future research. They close with a reconsideration of the typical team research investigation and call for scholars to embrace the complexity that surrounds modern team-based organizational designs as we move forward.

When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852

URL

PMID:16393020

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Procedures for examining whether treatment effects on an outcome are mediated and/or moderated have been well developed and are routinely applied. The mediation question focuses on the intervening mechanism that produces the treatment effect. The moderation question focuses on factors that affect the magnitude of the treatment effect. It is important to note that these two processes may be combined in informative ways, such that moderation is mediated or mediation is moderated. Although some prior literature has discussed these possibilities, their exact definitions and analytic procedures have not been completely articulated. The purpose of this article is to define precisely both mediated moderation and moderated mediation and provide analytic strategies for assessing each.

Global strategic linkages and industry structure

DOI:10.1002/smj.4250120909

URL

[本文引用: 1]

A theoretical framework is proposed to understand the structure of networks of strategic linkages in global industries. It is argued that global industry structure should be understood in terms of firm membership in `strategic groups' and `strategic blocks'. Strategic groups are based on similarities in the strategic capabilities of firms. Strategic blocks, on the other hand, are based on similarities in their strategic linkages. Two types of strategic blocks are proposed complementary blocks composed of firms from different strategic groups, and pooling blocks composed of firms from the same strategic group. It is further proposed that in equilibrium, each strategic block will have access to a similar set of strategic capabilities Empirical support for these arguments is drawn from the global automobile industry during the period 1980-90. The implications of strategic blocks for intra-industry performance differences are discussed in the concluding section of this paper

Outside directors and firm performance during institutional transitions

DOI:10.1002/smj.390

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Do outside directors on corporate boards make a difference in firm performance during institutional transitions? What leads to the practice of appointing outside directors in the absence of legal mandate? This article addresses these two important questions by drawing not only on agency theory, but also resource dependence and institutional theories. Taking advantage of China's institutional transitions, our findings, based on an archival database covering 405 publicly listed firms and 1211 company--years, suggest that outsider directors do make a difference in firm performance, if such performance is measured by sales growth, and that they have little impact on financial performance such as return on equity (ROE). The results also document a bandwagon effect behind the diffusion of the practice of appointing outsiders to corporate boards. The article not only highlights the need to incorporate multiple theories beyond agency theory in corporate governance research, but also generates policy implications in light of the recent trend toward having more outside directors on corporate boards in emerging economies.

Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies

DOI:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 URL [本文引用: 1]

Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions

DOI:10.1080/00273170701341316

URL

PMID:26821081

[本文引用: 1]