1 引言

“平出于公, 公出于道”, 自古以来公平就是人类社会所追求的价值理念。早期公平研究着眼于组织内分配公平, 随后拓展到程序公平和互动公平(Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter, & Ng, 2001), 相关研究证实了组织公平是预测员工行为和组织发展的重要因素, 它对员工和组织均有不可替代的作用(Colquitt et al., 2001; Skarlicki, O'Reilly, & Kulik, 2015)。经典组织公平理论通常从第一人视角探讨组织中的(不)公平事件, 它关注的是事件直接相关方的情绪体验和行为反应。但是, 公平有时不仅仅是当事双方的事情, 也可能会牵涉到与事件没有直接联系的第三方, 并影响他们的工作态度和行为。Colquitt (2004)认为, 组织公平研究如果能兼顾第一人视角和第三方视角, 这将比单一的第一人视角具有更强的解释效力。

Skarlicki和Kulik (2004)将“第三方”定义为通过直接或间接途径了解组织内部不公平事件, 进而形成组织公平印象的个体。Topa, Moriano和Morales (2013)进一步将“第三方”定义为在不公平事件中, 除当事人双方以外做出组织公平判断的个体。这些个体可以是投资者、消费者、政府官员、管理者、同事、下属和任何直接或间接了解不公平行为的个体(O'Reilly & Aquino, 2011)。国内学者原珂和齐亮(2015)认为所谓“第三方”是指与事件本身无利害关系, 采取一种围观和观望态度的旁观者, 具有模糊相关性、背景性和潜在参与性的特点。综合国内外学者的观点可知, 第三方的突出特征在于并非事件直接当事方但对事件公平性做出了判断。第三方视角下的组织公平(the third-party perspective of organizational justice), 又称作第三方组织公平, 存在“静态说”和“动态说”两类定义。Dunford, Jackson, Boss, Tay和Boss (2015)从静态角度认为第三方组织公平是第三方在见证组织不公平事件后形成的组织公平感知或组织公平印象。Bernerth和Walker (2012)将第三方组织公平界定为个人以全体组织成员是否得到公平对待为标准而形成的一种组织公平感知, 该种观点强调个人对组织公平整体性感知, 而不从某一具体事件出发。“动态说”则认为第三方组织公平是第三方从了解不公平事件到做出相应行为反应的一个动态过程, 包括组织内部不公平事件感知、形成道德情绪和进行干预等过程(马露露, 2016)。相比较而言, “动态说”不仅关注第三方组织公平感知的形成过程, 还研究之后的行为反应过程。为了更全面系统回顾已有成果, 本文从动态角度考察第三方组织公平。

现有研究表明, 组织公平在第一人称视角与第三方视角下存在明显差异。Skarlicki和Kulik (2004)把组织公平两种视角的差异性归纳为三个方面:(1)行为动机差异, 在组织不公平事件中, 受害方行为动机是为了维护自身利益, 而第三方行为动机更多是出于道德愤怒情绪和内心深处演化而来的公平偏好; (2)责任归因差异, Jones和Nisbett (1972)认为, 第三方相较于受害方在对事件后果进行责任归因时更容易归因于受害方自身因素; (3)信息获取差异, 第三方所获得到的信息常常是间接的, 受害方数量、侵害方的解释以及其他第三方的判断会影响到第三方组织公平感知。这种视角差异所导致的是两种完全不同的思维方式和情绪体验(Batson, Early, & Salvarani, 1997)。Topa等人也指出这种心理距离会导致对不公平事件后果严重性的评估差异。

鉴于第一人称视角和第三方视角对组织公平的认知与反应存在上述显著差异, 越来越多的学者开始以第三方视角去研究组织公平, 进一步完善组织公平的理论体系。那么, 从第三方视角看究竟何为组织公平?它对第三方行为有着怎样的影响?为了回答上述核心科学问题, 本文首先以如下步骤进行文献检索:(1)以“third party”或“observer”并含“justice”或“fairness”作为英文关键词在Web of Science、EBSCO、Wiley、ProQuest、Sciencedirect、Springer等英文数据库中检索; (2)以“第三方”或“旁观者”并含“公平”或“公正”为中文关键词在中国知网(CNKI)中文数据库中检索; (3)在Google Scholar通过检索词检索相关文献; (4)阅读所选文献的摘要, 剔除非组织情境下第三方公平的文章。然后, 文章从第三方组织公平的研究视角、责任归因、影响后果与两种作用机制、研究设计等四方面进行文献述评, 并在此基础上提出第三方组织公平未来研究的分析框架和重点方向。

2 第三方组织公平的研究视角

“路见不平, 拔刀相助。”第三方在面对不公平事件时为什么会产生相应行为反应?主流理论解释主要包括自利视角和道德视角(Cropanzano, Rupp, Mohler, & Schminke, 2001; Skarlicki & Kulik, 2004)。随着研究不断深入, 有学者整合自利视角和道德视角提出演化视角来解释第三方的公平反应(Skarlicki et al., 2015)。三种视角的对比参见表1。

表1 第三方组织公平研究视角对比

| 理论视角 | 代表性理论 | 核心观点 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 自利视角 | 工具视角 | 公平理论, 社会交换理论, 程序公平工具模型 | 第三方追求公平的目的是使自我经济利益最大化 |

| 关系视角 | 关系模型 | 第三方追求公平是为了获取良好的人际关系和社会地位 | |

| 道德视角 | 道义模型 | 第三方追求公平是基于责任、义务和道德 | |

| 演化视角 | 公平偏好理论, 强互惠理论 | 第三方追求公平源自进化过程中所形成的公平偏好 | |

资料来源:本研究根据相关文献整理

2.1 自利视角

自利视角在组织公平早期研究中占据主导地位(Skarlicki & Kulik, 2004; 任巍, 王一楠, 2016), 该视角主要通过工具视角和关系视角进行研究和阐述(Dunford et al., 2015; 马露露, 2016; 任巍, 王一楠, 2016)。工具视角观点认为人们为了维护自身物质利益而关注公平, 把公平作为一种使社会分配结果最优化的准则, 当违反公平准则的行为出现时, 人们自然会对其进行干预。关系视角则指出人们对于公平的关注是为了获得群体中的社会地位与良性的人际关系。关系模型聚焦于公平的象征意义, 认为公平有助于个人自尊和自我价值的实现(Tyler & Lind, 1992)。关系视角的核心观点是人们关注公平是由组织地位和人际关系所引起的, 第三方为了重构良性的人际互动和组织地位从而关注并干预不公平事件。综合工具视角和关系视角可知, 自利视角的研究认为第三方关注不公平事件是因为这些不公平事件引发了第三方对于自我利益的关注。第三方担心以后同样的不公平事件会降临到自己身上, 或者希望提升自己地位与价值, 因而对不公平事件做出相应的行为反应。

2.2 道德视角

20世纪80年代以来, 研究者逐渐认识到自利视角并不能解释所有公平行为。一系列实验发现人们愿意牺牲自己的部分利益去惩罚公平违背行为, 道德视角应运而生。道义模型认为公平维护行为不仅仅出于追求自我利益, 更是出于义务和美德, 并提出道义公平的概念。道义公平是指基于责任、义务和道德的一种个体动机, 强调每一个人都理应受到公平的对待(Folger, 2001; Cropanzano, Goldman, & Folger, 2003)。Cropanzano等人(2003)认为人们对不公平行为的道义判断优先考虑的是这些行为是否符合自身的道德体系, 而不会经过一个利益思考过程。在道义判断之后, 人们会产生道德愤怒情绪并采取干预措施惩罚违反道德的一方。也有批评者指出, 道义模型更多强调的是人们目睹不公平事件发生时所产生愤怒情绪和惩罚行为, 而忽视了第三方的其他行为反应。Rupp和Bell (2010)拓展了道义模型, 指出不应把第三方道义行为局限于惩罚行为, 道德自我调节下的不作为也是一种道义反应。O'Reilly和Aquino (2011)进一步将第三方补偿行为纳入道义模型。总体而言, 道德视角认为第三方关注不公平事件是因为不公平事件违背了道德准则, 激发了第三方的道德愤怒情绪。需要指出的是, 道德视角并没有否定人们追求经济利益和社会关系的公平动机, 而是强调获取利益时的道德性和利他性(任巍, 王一楠, 2016)。道德视角解释了第三方非自利情况下的公平维护行为, 进一步完善了公平行为驱动理论, 被学者所广泛引用和验证, 成为现有研究探讨第三方组织公平的主要理论视角。

2.3 演化视角

演化视角整合了自利视角和道德视角, 认为人们关注不公平事件是人类社会历史发展的必然结果。基于该视角, 第三方追求公平是人类进化过程中认知心理演化的结果, 尽管这些行为可能存在某种自利倾向, 但这种倾向是不为行为者所感知的(Skarlicki et al., 2015)。Fehr, Fischbacher和Gächter (2002)的强互惠理论支持了这一观点, 该理论认为人们愿意牺牲一些资源去善待好人, 也愿意牺牲一定资源去惩罚恶人, 同时还指出这种强互惠行为源于人类物种进化过程中所形成的利他倾向。Bowles和Gintis (2004)认为强互惠行为使早期人类开始演化出合作行为, 并会惩罚违反群体规范的成员, 从而提升了整个群体的生存竞争力和生存适应性。另一个支持演化视角的理论则是公平偏好理论。Fehr和Schmidt (1999)建立的不公平规避模型指出, 公平是基于人类内心深处的一种偏好, 当不公平的行为出现时, 人们会产生强烈的消除不公平的动机, 不惜牺牲自己的利益去实行惩罚行为。董志强等人(2011, 2015)通过随机演化仿真模型证明人类内心的公平偏好源于本能性的公平行为在人类早期进化过程中的适存性优势。

3 第三方组织公平的归因研究

面对同一组织(不)公平事件并非所有第三方都会产生相同感知与行为。第三方是否感到组织公平取决于其归因过程, 而事件因素、个体因素、人际关系因素和组织情境因素是第三方归因的主要内容(见表2)。

表2 第三方组织公平的归因研究

资料来源:本研究根据文献整理

3.1 事件因素

Folger和Cropanzano (2001)认为不公平事件会引发人们对事件后果的严重性、责任归因和违反道德的程度等三方面思考。Skarlicki和Kulik进一步指出不公平事件的后果越严重, 第三方就越容易感知到组织不公平。尽管对事件后果严重性的评判是主观的, 但也包含一些客观因素, 例如受害方经济损失、受害方数量等。事件系统理论也佐证了这一观点, 该理论指出事件的强度、时间和空间因素会决定该事件的影响大小(Morgeson, Mitchell, & Liu, 2015)。第三方在识别不公平事件后果的严重性后开始进行责任归因, 决定究竟谁应该为这一后果负责。责任归因过程被学界视为影响第三方组织公平感知的前提条件(Lind, Kray & Thompson, 1998; Folger & Cropanzano, 2001; Skarlicki & Kulik, 2004; Skarlicki et al., 2015; Mitchell, Vogel, & Folger, 2015), 只有将责任归因于侵害方, 第三方才有可能产生不公平感并做出反应; 若将责任归于受害方, 第三方则会认为受害方是罪有应得。Harlos和Pinder (1999)的研究表明, 组织不公平现象主要包括程序不公平、分配不公平、互动不公平和系统不公平。大量研究表明, 相较于分配不公平和程序不公平, 第三方在面对人际不公平时会产生更大的道德愤怒和不公平感知, 从而会加大对侵害方的惩罚力度(O'Reilly, Aquino, & Skarlicki, 2016)。

3.2 个体因素

3.2.1 侵害方因素

侵害方“有意侵害”的行为意图越强烈, 第三方的不公平感知就会越强烈。甚至侵害方仅仅是表露了不公平的行为意图都将会引发第三方的不公平感知(Umphress, Simmons, Folger, Ren, & Bobocel, 2013)。此外, 对于那些曾经违规的侵害方, 人们往往会不假思索地认为其重蹈覆辙(Skarlicki & Kulik, 2004)。Darby和Schlenker (1989)在传统二元关系下组织公平的研究表明, 孩童在面对有一个良好声誉、事后致歉且表达懊悔的侵害方时, 其责备和惩罚行为将会减轻。侵害方的声誉会决定其行为被冠以何种解释, 一个臭名远扬的侵害方的致歉行为会被认为是想减轻自己将遭受到的惩罚。Skarlicki和Kulik指出当侵害方在实施侵害行为后表露出喜悦之情, 第三方的不公平感知会因此而加强。CuguerÓ-Escofet, Fortin和Canela (2014)的研究表明侵害方的事后致歉和对于侵害行为的解释能够降低第三方所感知到的组织不公平, 上述研究均在第三方组织公平领域证实了Darby和Schlenker的观点。

3.2.2 受害方因素

受害方作为不公平事件的直接利益受损者, 其个人品质、情绪、认知和行为会在一定程度上影响第三方责任归因过程和不公平感知。研究表明, 受害方的组织承诺(Topa et al., 2013)和工作绩效(Niehoff, Paul, & Bunch, 1998; Topa et al., 2013)会对第三方的责任归因过程产生影响, 受害方的组织承诺和工作绩效越高, 第三方越有可能认为侵害方需要对此承担责任, 第三方的不公平感知也会越强烈。受害方的不公平感知也会影响到第三方的不公平感知, Umphress等人(2013)在研究中证实受害方的不公平感知和第三方不公平感知存在显著的正相关。方学梅(2009)指出受害方的愤怒情绪会引导第三方产生不公平感知, 羞愧情绪则导向第三方组织公平感知。研究还指出, 受害方“有意违规”的行为意图、为不公平待遇积极进行申诉的行为表现均会对第三方的不公平感知产生影响(Skarlicki & Kulik, 2004; Li, Mcallister, Ilies, & Gloor, in press)。

3.2.3 第三方自身因素

Skarlicki和Kulik认为在评估不公平事件后果严重性的过程中, 第三方个体的人格特点会影响对事件后果严重性的评判, 从而影响第三方组织公平知觉。例如, 自恋型人格的第三方往往不屑于去关注其他人所处的困境, 较不可能产生不公平的感知(Schwartz, 1975); 负面情绪越强的第三方越容易夸大事件后果的严重性, 从而产生组织不公平感知(Watson & Clark, 1984); 高权力距离的第三方会对侵害方(往往是上级或组织)持有一种恭敬和服从的态度, 从而抑制内心产生的不公平感知(Skarlicki et al., 2015)。第三方道德认同也是影响第三方组织公平的重要因素。第三方道德认同越高, 其对不公平事件进行干预的可能性也就越高(Skarlicki & Rupp, 2010; O'Reilly & Aquino, 2011; Mitchell et al., 2015; O'Reilly et al., 2016)。第三方的公正敏感性和公平世界信仰被证明与第三方组织公平感知负相关(Lotz, Baumert, Schlösser, Gresser, & Fetchenhauer, 2011a; 李哲, 2016; Zhu, Martens, & Aquino, 2012), 前者是指第三方对于自己或他人是否得到公平对待的关注情况, 而后者是指第三方坚信我们生活在一个多劳多得, 少劳少得, 有功必赏, 有过必罚的公平世界。双加工过程理论揭示出, 直觉反应主导的第三方其不公平感知会更强烈, 行为反应也会更剧烈(Skarlicki & Rupp, 2010; 刘燕君等, 2016)。此外, 第三方的组织认同越高, 越有可能将责任归因于受害方, 认为受害方是咎由自取(Topa et al., 2013)。

3.2.4 其他第三方因素

第三方的责任归因过程也会受到其他第三方的影响。由于第三方往往通过其他第三方间接了解不公平事件的信息, 根据社会信息理论, 其他第三方的态度、行为以及公平感知会显著影响第三方的公平判断(Skarlicki et al., 2015; Li et al., in press)。De Cremer, Wubben和Brebels (2008)以及李哲(2016)发现在事件信息模糊或者缺乏的情境下, 个体在感知到旁观者的愤怒情绪后, 更倾向于做出不公平的判断。

3.3 人际关系因素

文献研究可知, 第三方组织公平常常受到第三方与受害方之间人际关系的影响, 与受害方处于相同的职位、有着相似的经历的第三方更可能“拔刀相助”。Lind等(1998)以及Kray和Lind (2002)证实第三方往往会以自己过往经历去判断受害方的遭遇是否公平, 有过同样不公平对待的第三方更可能产生情感共鸣, 这种现象被称作“共同知识效应”。第三方与受害方之间特征的相似性越高, 其越有可能理解受害方的处境, 进而产生不公平判断(Gordijn, Wigboldus, Yzerbyt, 2001; Gordijn, Yzerbyt, Wigboldus, & Dumont, 2006)。双方之间社会情绪的一致性也会影响第三方的公平判断(Blader, Wiesenfeld, Fortin, & Wheeler-Smith, 2013), 社会情绪描述的是第三方对于受害方的整体态度, 当第三方对受害方的态度呈负面(讨厌、憎恨、嫉妒)时, 他会认为受害方是自作自受, 并且产生一种道德满意情绪。当第三方与受害方之间存在利益竞争关系时, 第三方产生不公平感知的概率显著降低, 相反会产生幸灾乐祸的情绪(Porath & Erez, 2009; Li et al., in press)。Gordijn等人(2001, 2006)认为, 第三方对侵害方和受害方所属群体的社会认同会显著影响其公平判断, 若第三方对受害方群体具有较高的社会认同, 则更可能将该事件视为不公平的。李哲(2016)和Li等人(2017)在不同国家情境下证实了Gordijn等人的研究结论。徐杰等人(2017)指出第三方与侵害方的社会距离越近, “亲亲相隐”发生的可能性越高, 关注到了第三方与侵害方之间的关系。

3.4 组织情境因素

组织情境同样影响第三方组织公平。第三方在责任归因和做出行为反应的过程中会受到组织政策、组织程序和组织气候的影响(Skarlicki & Kulik, 2004), 有学者证实了上述观点, 并且明确指出公平的组织气候与第三方组织公平感知正相关(Zhu et al., 2012; Topa et al., 2013), 即组织内部形成了一种公平的组织气候时, 组织成员认为上级的行为都是按照一种公平、合理、可靠的方式进行的, 更倾向于将事件视为公平的。

本文认为第三方组织公平归因研究尚存在一些局限性, 主要表现在如下方面:1)现有研究对于不公平事件因素的探索没有突破Folger和Cropanzano (2001)的公平理论, 局限于对后果严重性、责任归因和违反道德程度的关注, 忽略了信息披露程度等其他事件因素对于第三方组织公平的影响; 2)现有研究在考察人际关系因素时聚焦于受害方与第三方之间的关系, 而较少涉及侵害方与第三方、侵害方与受害方之间的关系; 3)现有研究仅关注其他第三方的情绪和认知因素, 而忽略了其他第三方的行为反应对第三方组织公平的影响; 4)现有的归因研究主要集中于个体因素, 对组织情境的因素关注较少。事实上, 第三方组织公平产生于特定情境下侵害方、受害方和第三方的社会互动过程, 受到各层次因素共同作用, 即事件因素、个体因素、人际关系因素和组织情境因素往往共同影响第三方组织公平感知。后续关于影响因素的研究一方面应该基于事件系统理论, 探讨事件强度属性(事件新颖性、颠覆性和关键性)、时间属性(事件时机、时长和变化)和空间属性(事件起源、扩散和距离)对第三方组织公平的影响; 另一方面应该重视组织情境因素, 关注竞争性或合作性组织文化与不同领导风格会对第三方组织公平感知产生何种影响, 并探讨多种因素之间的相互作用, 开展第三方组织公平跨层次研究。

4 第三方组织公平的影响后果与两种机制

4.1 主要影响后果

学界对第三方组织公平影响后果的研究主要关注第三方产生不公平感知后的行为反应, 聚焦于三种行为取向:一种是倾向于惩罚侵害方的报复取向, 即惩罚行为; 一种是倾向于补偿受害方的恢复取向, 即补偿行为; 另一种是倾向于不进行干预的维持取向, 即漠视行为。惩罚行为也称作第三方惩罚, 指第三方通过报复、攻击、惩罚侵害方的方式来维护公平, 通常导致侵害方利益受损、名誉败坏或是权利被剥夺(Okimoto, Wenzel, & Feather, 2012)。惩罚行为通过降低侵害方的地位或将其排除于群体之外等方式来维护群体价值准则(Okimoto et al., 2012)。该行为被视为可以遏制侵害方不公平的行为意图, 从而满足第三方的公平偏好。补偿行为是通过给予受害方适当的金钱补助或是提供某种情感支持等方式来维护公平, 结果是在受害方和侵害方之间重新构建公平关系, 并使受害方恢复到未被侵害前的状态。这种补偿性公平除了关注受害方之外, 还指出要重塑侵害方的道德观念、强化群体价值规范和修补被破坏的社会关系(Okimoto, Wenzel, & Feather, 2009, 2012)。漠视行为是指第三方在产生组织不公平感知后采取“事不关己高高挂起”的态度, 选择不干预组织不当行为, 其结果往往是第三方产生某种内疚情绪(Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994)。采取漠视行为的第三方往往会通过重新对组织不当行为进行归因或是将受害方视为外群体成员来努力消除内心的愧疚情绪, 从而维护公平世界信仰和保持正面的自我认知(Baumeister et al., 1994; Skarlicki et al., 2015)。

相较于第三方不公平感知, 第三方组织公平感知下的行为研究仍处于起步阶段, 研究结果指出当第三方认为事件的发生是公平合理的时候, 会产生一种道德满意情绪, 甚至排挤受害方(Feather, 2006; Mitchell et al., 2015)。Li等人(in press)也指出, 当第三方认为受害方罪有应得时会产生“正义的幸灾乐祸” (righteous schadenfreude), 进而通过传播流言蜚语、拒绝提供帮助等形式来排挤受害方。排挤行为是第三方做出组织公平判断后的主要行为反应, 具体表现为第三方通过排挤、孤立等方式来疏离与受害方的距离, 将其排除于群体之外以维护群体价值规范, 其结果往往是第三方与受害方之间的关系冲突(Farh & Chen, 2014)。

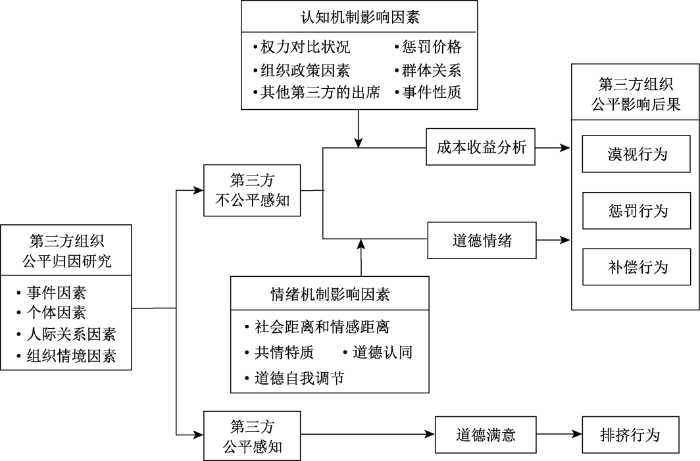

第三方组织公平如何导致第三方上述不同行为反应?根据双加工过程理论、认知-情感加工系统、认知-经验理论以及与思维过程有关的研究(Skarlicki et al., 2015; 刘燕君等, 2016; 马露露, 2016), 第三方主要通过理性思考过程和直觉反应过程来选择行为反应, 分别形成第三方组织公平影响第三方行为反应的认知机制和情绪机制。认知机制中, 第三方有意地将情绪合理化, 仔细权衡客观的事实情况和对错标准, 推理和分析利弊关系来选择采取何种行为反应; 情绪机制中, 第三方往往根据其直觉、过去的经历和道德情绪来选择采取干预措施。

4.2 认知机制

理性思考过程下的第三方会试图压抑内心产生的负面情绪并努力使之合理化, 往往通过成本收益分析之后再做出相应的行为反应, 也被称为理性主义。成本收益分析的内容主要包括权力对比状况、惩罚价格、组织政策、群体关系、其他第三方的出席等。1)权力对比状况。O'Reilly和Aquino (2011)指出第三方将会与侵害方比较职位权力和衡量资源权力的绝对值, 在其职位权力高于侵害方时选择采取惩罚行为, 其资源权力绝对值高时选择补偿行为, 若职位权力和资源权力皆高则会惩罚与补偿并用, 若皆低则会袖手旁观。Hershcovis等人 (2017)的研究证实权力会正向影响第三方惩罚行为, 负向影响补偿和漠视行为, 且这种影响效应被责任感所中介。2)惩罚价格。第三方惩罚行为往往被视为需要牺牲自身利益的利他行为, 因此惩罚价格的高低是影响第三方是否进行惩罚行为的一个重要因素(Baker, 1974; 范良聪, 刘璐, 梁捷, 2013)。3)组织政策。Skarlicki等人(2004, 2015)认为第三方以个人力量去对抗上级或组织会感到力不从心, 常常会考虑到是否存在支持性的组织政策、组织程序和组织气候。当组织内部存在对报复行为的惩戒机制时, 第三方会更勇于干预不公平事件。当组织具有完善的不公平行为惩戒机制时, 第三方的干预行为会大大减少并被视为没有必要(O'Reilly & Aquino, 2011)。4)群体关系。Bernhard, Fischbacher和Fehr (2006)实验发现, 第三方对于组织内部受害方的补偿力度明显大于对于组织外部受害方的补偿力度, 对于组织外部侵害方的惩罚力度远大于对组织内部侵害方的惩罚力度。Schiller, Baumgartner和Knoch (2014)将这种现象称之为群体偏差, 并指出这是内群体偏好和外群体偏见共同作用的结果。当第三方与侵害方有一个共同的身份, 属于同一个群体或是有着亲密的人际关系时, 他们之间就会存在一种共同认知, 此时第三方更倾向于选择补偿行为(Okimoto et al., 2009)。5)其他第三方的出席。旁观者效应同样适用于第三方组织公平。当有其他第三方在场时, 第三方对不公平事件进行干预的可能性大大降低(Skarlicki & Kulik, 2004; Skarlicki et al., 2015)。6)事件性质。Liu, Li, Zheng和Guo (2017)发现当不公平事件是受益事件(如利益分配)时, 第三方偏好惩罚行为, 而当不公平事件是受损事件(如责任分担)时, 第三方进行干预的可能性更大, 并且偏好于补偿行为。除此之外, Darley和Pittman (2003)研究表明, 当侵害方的行为不是有意而为之的时候, 第三方更倾向于选择补偿行为。

4.3 情绪机制

直觉反应过程下的第三方往往以直觉和道德情绪为基础来选择采取何种行为反应, 也被称作是直觉主义。有关情绪机制的众多研究表明第三方的惩罚行为与道德愤怒显著相关, 而补偿行为的情绪体验则饱受争议。在本世纪初期, 研究者甚至使用低道德愤怒(low moral anger)来预测第三方的补偿行为(Darley & Pittman, 2003)。随着研究的不断深入, Wenzel, Okimoto, Feather和Platow (2010)指出悲伤、失望等道德失落情绪(moral loss)与第三方的补偿行为存在关联。Lotz, Okimoto, Schlösser和Fetchenhauer (2011b)则指出自我聚焦情绪下所产生恐惧、焦虑和愧疚等情绪预测第三方的补偿行为。后续研究应进一步关注补偿行为的情绪机制, 明晰第三方的情绪体验与行为反应之间的内在联系。van Prooijen (2010)发现在第三方与受害方的社会距离和情感距离较远的情况下, 第三方会更偏好于惩罚侵害方而不是补偿受害方, 反之则更偏好于补偿行为, 该结论也在中国情境下得以证实(徐杰等, 2017)。Rupp和Bell对道义模型进行了拓展, 指出道德自我调节也是一种道义反应, 高道德自我调节力的第三方会对自身行为进行自我调节, 抑制惩罚侵害方的行为意图, 避免造成持续性的负面影响。Mitchell等人(2015)指出道德认同作为以道德为中心构建的一种个人自我概念, 具有加强伦理行为, 削弱非伦理行为的作用, 据此, 道德认同高的第三方更有可能去补偿受害方, 而不是去惩罚侵害方。Mitchell等人的研究还表明道德认同在道德情绪和行为反应之间起调节作用。Skarlicki和Rupp (2010)对185位法国管理人员的实证研究也发现, 第三方的道德认同调节信息加工方式和行为反应之间的关系, 第三方的道德认同越高, 其行为反应就越不容易受到信息加工方式的影响。

文献研究发现, 第三方行为反应是多样化的, 每一种行为都有其产生机制和产生条件。比较而言, 尽管研究表明实际生活情境中第三方更偏好于选择补偿行为, 并且补偿行为相较于惩罚行为而言更具有公平恢复效用(Lotz et al., 2011b; 马露露, 2016), 但是补偿行为远不如惩罚行为研究成果丰富, 既有研究尚未对第三方补偿行为及其发生机制达成共识。此外, 现有研究过多关注了第三方不公平感知下的行为反应, 第三方做出组织公平判断后的行为反应未受到研究者们关注。当第三方认为事件的发生公平合理时, 除了产生道德满意情绪和排挤受害方以外, 其是否会增加对组织的信任或是向组织上级靠拢?后续研究应该更深入探讨第三方补偿行为和漠视行为, 探索第三方做出组织公平判断后的情绪体验和行为反应。最后, 无论是认知机制还是情绪机制的研究都侧重于考查第三方视角下组织公平对第三方个体行为的影响机理。事实上, 第三方组织公平及其反应可能成为直接当事方行为反应的重要影响因素, 但是, 现有机制研究尚未涉及到第三方组织公平及其反应如何进一步影响直接当事方的行为反应。这值得引起未来研究的关注。整合研究内容, 我们给出第三方组织公平研究框架(见图1)。

图1

5 第三方组织公平的研究设计

相比较而言, 组织公平第三方视角的研究难于第一人称视角的研究, 主要原因在于前者的研究设计更为复杂, 研究者必须营造一种包括直接当事方和第三方在内的三元关系情景, 并由此获得能够反应或影响第三方行为的相关变量的数据, 这增加了数据测量难度。文献回顾发现, 学者们开展第三方组织公平研究时主要采用三种方法获得所需数据, 即资源分配法、故事描述法和问卷调查法。本文认为这三种方法各有利弊和其适用性。

5.1 资源分配法

资源分配法主要研究分配不公平情境下人们的行为反应。Baker (1974)最早运用资源分配实验去研究第三方组织公平, 其实验包括两个阶段:首先在两个参与者之间进行不公平的分配, 然后引入利益无关的第三方去选择是否改变这种不公平的状况。最具代表性的资源分配法是Fehr和Fischbacher (2004)在独裁者博弈基础上引入第三方而创立的第三方惩罚博弈, 为后续研究者所广泛应用(Charness, Cobo-Reyes, & JimÉnez, 2008; Lotz et al., 2011b; 范良聪等, 2013; 马露露, 2016; Gummerum, Dillen, Dijk, & LÓpez-PÉrez, 2016)。第三方惩罚博弈由提议者、接受者和旁观者三个实验参与人组成。提议者提出资源分配方案, 接受者只能被动接受提议者的分配方案。第三方作为旁观者观察提议者和接受者的博弈, 决定是否牺牲自己的利益来减少提议者的收益, 实验结果往往是第三方愿意牺牲自己的利益来惩罚提议方。第三方惩罚博弈的缺陷在于只关注到了第三方的惩罚行为, 但随着研究的不断深入, 后续研究者对此进行了优化, 探讨了第三方的补偿行为(Lotz et al., 2011; 马露露, 2016)。资源分配法操作简单, 被试能够直观地评价分配的公平与否, 符合现实生活情境, 但是往往局限于对分配不公平和第三方惩罚行为的研究。未来研究应突破第三方惩罚博弈的局限, 不对被试的行为反应进行限制, 即被试可以自主选择任意行为, 而不局限于是否惩罚侵害方。

5.2 故事描述法

故事描述法通常是研究者向被试描述某一真实发生在工作场合的不公平遭遇, 由此来考察第三方的行为反应(Skarlicki & Rupp, 2010; Blader et al., 2013; O'Reilly et al., 2016)。该方法常常描述的是与被试利益无关的同事的遭遇来向被试传递组织不公平的信息, 例如通过描述一位同事经常受到上级辱骂和欺凌来体现人际不公平(O'Reilly et al., 2016)。与故事描述法相类似的还有回忆法, 主要要求被试回忆在工作过程中所目睹到的不公平事件(Topa et al., 2013)。故事描述法突破了资源分配法的局限性, 将研究领域拓展到了人际不公平和信息不公平, 同时也关注第三方的其他反应行为。该方法对情境设置要求严格, 故事信息的接受程度因人而异, 往往会受到其他因素的干扰。

5.3 问卷调查法

问卷调查法是研究和测量第三方组织公平最为直接的方法, 可以同资源分配法和故事描述法搭配使用(Topa et al., 2013; O'Reilly et al., 2016), 也可以单独进行测量(Bernerth & Walker, 2012)。第三方组织公平的测量问卷往往是基于传统组织公平领域的成熟量表发展而来。Bernerth和Walker在Fedor, Caldwell和Herold (2006)量表基础上对题项进行适度修改来测量第三方组织公平, 例如将“变革的结果对我是否公平”修改为“变革的结果对所有员工是否公平”, 改良后问卷的Alpha系数为0.88, 表明其测量结果具有较高的信度。问卷调查法操作简易, 结果表示清楚, 便于统计分析, 但是其主观填写的因素会导致测量结果受到社会环境的影响。

第三方组织公平的现有研究采用的大都是量化分析和实验室实验方法, 将数据收集与分析割裂开来, 在研究设计方面限制第三方行为反应, 一定程度上偏离了人们的工作实践。基于资源分配法和故事描述法的研究多着眼于侵害方、受害方和第三方这三者实体的“稳定特征”, 诸如个人品质和组织情境等特征因素。后续研究在方法上可以借助事件系统理论, 着眼于实体间的相互作用和外在动态经历所构成的事件系统, 根据事件的强度、时间和空间特征来量化事件(刘东, 刘军, 2017), 并在此基础上考察第三方组织公平的产生与演化机制。基于问卷调查法的研究因为所用量表缺乏扎根基础而难以完整测量第三方组织公平, 建议未来研究基于扎根理论, 通过质性研究方法收集有关研究环境、研究对象以及研究对象对自身行为解释的资料, 然后通过一系列的编码分析来开发第三方组织公平的测量量表, 把质性研究和量化研究有机结合以更深入考察第三方组织公平的形成过程和行为反应机制, 丰富第三方组织公平理论模型。

6 总体评价与未来展望

6.1 总体研究评价

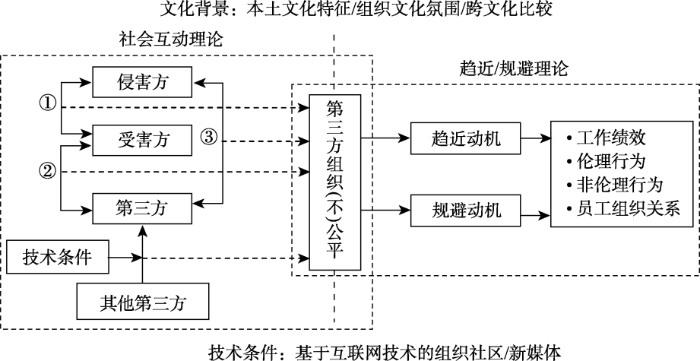

第三方组织公平经过了国内外学者近20年的探索与研究已经取得一定进展, 既有研究成果对于人们理解第三方组织公平感知的形成过程以及第三方行为反应机制富有启发意义。但是, 现有研究框架也存在一些不足之处, 主要表现在三个方面:(1)基于自利视角、道德视角和演化视角的现有研究有利于人们理解第三方组织公平是什么, 但没有充分考虑公平事件当事方和第三方彼此之间的社会互动因素对第三方组织公平的影响, 缺乏三元关系情景下第三方组织公平与事件直接相关方组织公平之间的交互影响方面的研究, 对第三方组织公平产生机制的解释存在不足; (2)在讨论第三方组织公平影响后果时, 研究者过多地关注于第三方针对公平事件当事方的行为反应, 例如惩罚行为、补偿行为或者漠视行为等, 忽视了第三方针对组织整体的行为反应, 例如第三方组织公平如何影响第三方的工作动机从而影响其工作绩效和职场伦理行为等, 后者才是更具有管理价值的主题; (3)当前研究主要基于西方文化背景展开, 但是中国本土文化非常强调差序格局、中庸价值观、集体主义等特质, 既有研究成果尚不能回答这些本土文化因素及其演化而来的组织文化氛围是否对第三方组织公平产生差异化影响; 并且, 信息技术的发展为事件当事方和第三方彼此之间的社会互动提供了实时性的沟通平台, 成为影响第三方组织公平的重要技术条件。

6.2 未来研究框架与重点方向

第三方组织公平本质上是在侵害方、受害方和第三方这一三元互动关系情境下探讨组织公平问题。根据社会互动理论, 自我的产生是一个社会过程, 是在个体参与社会互动过程中形成的(米德, 1934/2012)。三元关系情境下, 任意双方之间的社会互动都可能是影响第三方公平感知的重要因素。基于上文述评所归纳的现有研究不足, 结合社会互动理论和趋近/规避理论, 本文提出一个指导第三方组织公平未来研究的理论框架(见图2), 图中路径①、②、③分别代表社会互动理论下侵害方、受害方与第三方彼此之间的社会互动过程。该框架在前因变量部分纳入侵害方、受害方与第三方之间的社会互动以及组织社区和新媒体等技术因素; 在作用机制部分以趋近/规避动机理论为视角考虑第三方组织公平对第三方工作绩效、(非)伦理行为和员工组织关系等的影响; 并探讨本土文化特征或者组织文化氛围对第三方组织公平影响以及不同文化背景下第三方组织公平的差异。根据这一理论框架, 本文给出了学界未来需要重点关注的研究方向。

图2

(1)以社会互动理论为基础, 关注侵害方、受害方与第三方之间的社会互动对第三方组织公平的影响。侵害方、受害方与第三方两两之间的社会互动主要涉及地位竞争、利益格局和心理距离, 分别对应着互动双方在权力、金钱和情感三个基本方面的相互关系。Porath和Erez (2009)的研究已证明当第三方与受害方之间存在利益竞争关系时, 其产生不公平感知和消极情绪的概率会大大降低。不仅第三方与侵(受)害方之间地位竞争、利益博弈和心理距离会影响到第三方组织公平, 侵害方与受害方之间的社会互动也会对第三方组织公平产生影响。例如, 当侵害方与受害方同属一个“圈子”时, 会引导第三方认为侵害行为是“一个愿打, 一个愿挨”的圈内现象, 进而不会产生不公平感知。未来研究不仅应关注社会互动对公平感知形成过程的影响, 也应该关注此种社会互动是否会影响到第三方的行为反应。

(2)基于趋近规避理论在三元关系情景下研究第三方组织公平的影响后果与机制。趋近规避理论认为, 人存在趋近动机和规避动机两个系统(Eder, Elliot, & Harmon-Hones, 2013)。越来越多的研究显示在紧密的人际关系情景下趋近目标和规避目标分别与不同的结果相连(Gable & Impett, 2012)。就组织公平问题而言, 趋近动机可能使第三方导向积极的干预行为, 规避动机则可能使第三方导向消极的不作为, 从而影响第三方的工作绩效、组织态度、职场伦理或非伦理行为。后续研究可以基于趋近规避理论的理论框架, 探讨第三方针对组织公平与否的趋避反应模式, 以及第三方趋避反应如何进一步影响直接当事方的态度与行为。

(3)考虑文化差异, 进行第三方组织公平的跨文化比较研究。目前有关第三方组织公平的研究结果大都是由西方学者在西方的文化情境下得出的, 国内对于第三方组织公平的研究处于初步探索阶段。那么这种在西方情境下提出的第三方组织公平又是否在中国特殊情境下存在呢?西方强调法治社会, 重视制度与规则; 而中国则是一个关系社会, 以“差序格局”、“中庸文化”、“集体主义”等为特征。此外, 中国是一个高权力距离的国家, 再加之国人善于隐忍, 坚信以和为贵。文化差异是否导致第三方的不同行为反应模式?此外, 技术革命的蓬勃发展使得全球多个领域逐渐沿着互联网逻辑演化, 传统的层级与结构进一步转向开放、分散的网络结构, 进而对社会权力格局与规则产生革命性的影响。在这种新型权力背景下第三方公平感知的形成过程和行为反应的差异也需要引起重视。未来研究不仅需要关注不同国家间的文化差异, 也需要关注同一国度下不同权力背景下的组织文化差异, 探讨第三方组织公平产生机制和影响机制的跨文化异同。

(4)结合时代特点, 探寻新媒体对第三方组织公平的影响。随着互联网和通信技术的快速发展, “网络围观”事件变得十分普遍。Skarlicki, O'Reilly和Kulik指出不公平事件的目击者或是受害方会在社交网络上匿名发表一些对不公平事件的描述, 这些描述往往经过个人的感情加工, 会使用情绪语句将事件描述得更加不公平。这种情绪化的描述甚至会改变公众的观点, 对第三方的公平感知产生重要的影响。可见, 网络技术的发展彻底打破了信息传递的时空限制, 会大大增加第三方产生不公平感知的可能性。此外, 新媒体的普及还会使得第三方接触到更多的其他第三方, “网络围观”调动了人们的参与热情, 热烈的网络讨论往往会推动事件的发展, 影响第三方的公平感知和行为反应。因此, 未来研究需要从信息传播的角度探讨新媒体对第三方组织公平的影响。

参考文献

再论公平偏好的演化起源:改进的仿真模型

"公平偏好演化起源"模型预设了19种要价类型,因而其中的公平偏好社会并非自然"演化"而来;同时,该模型一定程度上依赖群体选择理论。本文对其仿真模型做出重要改进,允许各要价类型在[0,1]区间上连续分布,且完全不考虑群体竞争,因而公平偏好主导整个社会将是在[0,1]区间遍历演化的结果,是真正自然"演化"而来的,无须依赖群体选择。运用不同参数进行上百次仿真实验的结果表明,最终的演化稳定均衡是公平偏好主导整个社会。原因在于,相对公平的要价最能实现合作机会多寡和合作利益大小的平衡,从而最具适存性。上述结果对"公平演化起源"思想提供了更加有力的支持。

第三方的惩罚需求:一个实验研究

第三方惩罚对于社会规范的维持至关重要。本文基于一组引入真实劳动(real effort)和第三方的独裁者博弈实验,探讨了由利益无关的第三方实施的惩罚背后隐藏的经济逻辑。本文研究的问题是,利益无关的第三方对惩罚的需求是否敏感反应于惩罚价格?本文通过操控实验中独裁者做出分配决策后第三方面对的惩罚价格检验了这一点。结果发现,第三方确实愿意花费成本惩罚违背潜在规范的独裁者。第三方对惩罚的这种需求一方面随着惩罚价格的上升而下降,另一方面随着独裁者规范违背程度的增加而增加。通过引出接受者关于第三方在给定惩罚价格水平下是否会实施惩罚的信念,本文证明了这种动机模式的普遍性。本文的结论是,即便利益无关,第三方惩罚这种看似纯粹利他的行为背后也存在很强的经济考虑。这意味着,我们在构建有关惩罚的微观行为模型进而进行相应的制度设计时必须同时考虑这两个方面。

理性-经验加工对不公正情绪和行为反应的影响:公正敏感性的调节作用

心灵、自我和社会

(霍桂恒译).

人情与公正的抉择:社会距离对第三方干预的影响

第三方干预(third-party intervention)是一种重要的利他行为,它包括惩罚和补偿两种措施。本研究结合情境性问卷与实验法,采用修改后的独裁者博弈范式(Dictator Game,DG),让被试作为第三方对朋友或者陌生人的不公平行为进行干预,考察社会距离对第三方干预的影响。研究发现:(1)对于朋友提出的不公平方案,个体对其的惩罚轻于陌生人,而对第二方(无权者)的补偿没有显著差异。(2)个体对朋友的不公平提议的公平性判断高于陌生人,但提议引发的情绪体验没有显著差异。上述结果表明,社会距离可能通过影响个体对不公平行为的公平感知,进而影响其第三方干预行为。

Experimental analysis of third-party justice behavior

DOI:10.1037/h0036623

URL

[本文引用: 2]

ABSTRACT Conducted 3 experiments with a total of 119 college students to examine the effects of an inequity between 2 others on the behavior of a third party toward those 2 others. Ss were put in a position of power over the allocation of rewards received by 2 others in an existing inequitable state. It was found that (a) the third party acted to maintain equity or to reduce inequity between 2 others; (b) as maintenance of equity became more costly to the third party, it became less likely that he would act to maintain equity between the 2 others; (c) the third party gave more rewards to the person who became disadvantaged by the inequity as a result of prior harmful behavior by the person advantaged by the inequity, and gave fewer rewards to a person disadvantaged in spite of helpful behavior by the person advantaged by the inequity. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)

Perspective taking: Imagining how another feels versus imagining how you would feel

DOI:10.1177/0146167297237008

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Although often confused, imagining how another feels and imagining how you would feel are two distinct forms of perspective taking with different emotional consequences. The former evokes empathy; the latter, both empathy and distress. To test this claim, undergraduates listened to a (bogus) pilot radio interview with a young woman in serious need. One third were instructed to remain objective while listening; one third, to imagine how the young woman felt; and one third, to imagine how they would feel in her situation. The two imagine perspectives produced the predicted distinct pattern of emotions, suggesting different motivational consequences: Imagining how the other feels produced empathy, which has been found to evoke altruistic motivation; imagining how you would feel produced empathy, but it also produced personal distress, which has been found to evoke egoistic motivation.

Guilt: An interpersonal approach

Reexamining the workplace justice to outcome relationship: Does frame of reference matter?

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00977.x

URL

[本文引用: 2]

abstractUsing a combination of self-interest and deontological theories as justification, we propose a demarcated view of workplace justice that separates justice for an individual (personal justice) and inferred assessments of justice for organizational members (third party justice). Results of two studies confirmed the appropriateness of separate justice measures and demonstrated differential effects on key criteria based on the relevancy (personal or joint) of the outcome in question. Specifically, Studies 1 and 2 found that personal justice was a better predictor of organizational commitment and turnover intentions while third party justice was more closely related to workplace cohesion (Study 1), citizenship behaviours (Study 2), and deviance behaviours (Study 2). Implications of these findings and future research needs are discussed.

Parochial altruism in humans

Fairness lies in the heart of the beholder: How the social emotions of third parties influence reactions to injustice

DOI:10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.12.004

URL

[本文引用: 3]

The present research explores third parties’ (e.g., jurors, ombudsmen, auditors, and employees observing others’ encounters) ability to objectively judge fairness. More specifically, the current research suggests that third parties’ justice judgments and reactions are biased by their attitudes toward the decision recipient and, in particular, the affective aspect of those attitudes as characterized by their felt social emotions. We explore how the congruence of a social emotion (i.e., the extent to which the emotion reflects feeling a subjective sense of alignment with the target of the emotion) can influence their evaluations of recipients’ decision outcomes. The five studies presented show that congruence can lead third parties to react positively to objectively unfair decision outcomes and, importantly, that the influence of social emotions on subjective justice judgments drive third party reactions to decisions, decision makers, and even national policies.

The evolution of strong reciprocity: Cooperation in heterogeneous populations

DOI:10.1016/j.tpb.2003.07.001

URL

PMID:14642341

[本文引用: 1]

How do human groups maintain a high level of cooperation despite a low level of genetic relatedness among group members? We suggest that many humans have a predisposition to punish those who violate group-beneficial norms, even when this imposes a fitness cost on the punisher. Such altruistic punishment is widely observed to sustain high levels of cooperation in behavioral experiments and in natural settings.We offer a model of cooperation and punishment that we call strong reciprocity: where members of a group benefit from mutual adherence to a social norm, strong reciprocators obey the norm and punish its violators, even though as a result they receive lower payoffs than other group members, such as selfish agents who violate the norm and do not punish, and pure cooperators who adhere to the norm but free-ride by never punishing. Our agent-based simulations show that, under assumptions approximating likely human environments over the 100,000 years prior to the domestication of animals and plants, the proliferation of strong reciprocators when initially rare is highly likely, and that substantial frequencies of all three behavioral types can be sustained in a population. As a result, high levels of cooperation are sustained. Our results do not require that group members be related or that group extinctions occur.

An investment game with third-party intervention

DOI:10.1016/j.jebo.2008.02.006

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This paper explores the effect of the possibility of third-party intervention on behavior in a variant of the Berg et al. [Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., McCabe, K., 1995. Trust, reciprocity and social history. Games and Economic Behavior 10, 122–142] “Investment Game”. A third-party's material payoff is not affected by the decisions made by the other participants, but this person may choose to punish a responder who has been overly selfish. The concern over this possibility may serve to discipline potentially selfish responders. We also explore a treatment in which the third party may also choose to reward a sender who has received a low net payoff as a result of the responder's action. We find a strong and significant effect of third-party punishment in both punishment regimes, as the amount sent by the first mover is more than 60% higher when there is the possibility of third-party punishment. We also find that responders return a higher proportion of the amount sent to them when there is the possibility of punishment, with this proportion slightly higher when reward is not feasible. Finally, third parties punish less when reward is feasible, but nevertheless spend more on the combination of reward and punishment when these are both permitted than on punishment when this is the only choice for redressing material outcomes.

Justice at the millennium: A meta- analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research

Does the justice of the one interact with the justice of the many? Reactions to procedural justice in teams

Deontic justice: The role of moral principles in workplace fairness

DOI:10.1002/job.228

URL

[本文引用: 4]

First page of article

Three roads to organizational justice

Righting the wrong for third parties: How monetary compensation, procedure changes and apologies can restore justice for observers of injustice

DOI:10.1007/s10551-013-1762-7

URL

[本文引用: 3]

People react negatively not only to injustices they personally endure but also to injustices that they observe as bystanders at work nd typically, people observe more injustices than they personally experience. It is therefore important to understand how organizations can restore observers perceptions of justice after an injustice has occurred. In our paper, we employ a policy capturing design to test and compare the restorative power of monetary compensation, procedure changes and apologies, alone and in combination, from the perspective of third parties. We extend previous research on remedies by including different degrees of compensation and procedural changes, by comparing the effects of sincere versus insincere apologies and by including apologies from additional sources. The results indicate that monetary compensation, procedure changes, and sincere apologies all have a significant and positive effect on how observers perceive the restoration of justice. Insincere apologies, on the other hand, have no significant effect on restoration for third parties. Procedural changes were found to have the strongest remedial effects, a remedy rarely included in previous research. One interpretation of this finding could be that observers of injustice prefer solutions that are not short sighted: changing procedures avoids future injustices that could affect other people. We found that combinations of remedies, such that the presence of a second remedy strengthens the effect of the first remedy, are particularly effective. Our findings regarding interactions underline the importance of studying and administering remedies in conjunction with each other.

Children's reactions to transgressions: Effects of the actor's apology, reputation and remorse

DOI:10.1111/j.2044-8309.1989.tb00879.x

URL

PMID:2611611

[本文引用: 4]

This experiment examined children's reactions to a transgression in which one child's property was damaged by another who (a) had a reputation as a good or bad child, (b) apologized or did not, and (c) later expressed remorse when talking about the incident or was happy and unremorseful. As expected, actors who had a good reputation or were remorseful were seen as more likable, as having better motives, as doing the damage unintentionally, as more sorry and as less blameworthy. Further, actors who were good and remorseful were punished least, suggesting that punishment was applied in a rehabilitative fashion. The actor's reputation determined how his or her actions were interpreted: bad actors were seen as more worried about punishment when they expressed remorse and older children thought they apologized merely to avoid punishment. Interestingly, apologies were effective in reducing punishment and making the actor seem more likable, and this was true irrespective of the other factors. The apology-forgiveness script may be such an ingrained aspect of social life that its appearance automatically improves the actor's position. The reactions of second and fifth graders were generally similar, although the younger children displayed less coherent relationships between judgements.

The psychology of compensatory and retributive justice

When unfair treatment leads to anger: The effects of other people's emotions and ambiguous unfair procedures

DOI:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00402.x

URL

[本文引用: 2]

The present research examines how emotions of a third party interacting with an authority who has treated him or her unfairly affect one's feelings of anger toward the authority as a function of the ambiguity of the unfair treatment. Across a scenario and a laboratory study, it was found that when participants did not receive voice and it was unclear whether this was the result of an authority's unfair intentions, participants were less angry when the third party expressed shame, rather than anger, toward the same enacting authority. A second laboratory study replicated this effect, but now by showing that one's feelings of anger (in the case of ambiguity) were lower when the other person expressed guilt, relative to anger.

Be fair, your employees are watching: A relational response model of external third‐party justice

DOI:10.1111/peps.12081

URL

[本文引用: 1]

ABSTRACT There is growing theoretical recognition in the organizational justice literature that an organization’s treatment of external parties (such as patients, community members, customers, and the general public) shapes its own employees’ attitudes and behavior toward it. However, the emerging third-party justice literature has an inward focus, emphasizing perceptions of the treatment of other insiders (e.g., co-workers or team members). This inward focus overlooks meaningful “outward” employee concerns relating to how organizations treat external parties. We propose a relational response model to advance the third-party justice literature asserting that the organization’s fair treatment of external parties sends important relational signals to employees that shape their social exchange perceptions toward their employer. Supporting this proposition, in two multi-source studies in separate healthcare organizations we found that patient-directed justice had indirect effects on supervisory cooperative behavior ratings through organizational trust and organizational identification.

Approach and avoidance motivation: Issues and advances

DOI:10.1177/1754073913477990

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This article has no associated abstract. ( fix it )

Beyond the individual victim: Multilevel consequences of abusive supervision in teams

DOI:10.1037/a0037636

URL

PMID:25111251

[本文引用: 1]

We conceptualize a multilevel framework that examines the manifestation of abusive supervision in team settings and its implications for the team and individual members. Drawing on Hackman's (1992) typology of ambient and discretionary team stimuli, our model features team-level abusive supervision (the average level of abuse reported by team members) and individual-level abusive supervision as simultaneous and interacting forces. We further draw on team-relevant theories of social influence to delineate two proximal outcomes of abuse-members' organization-based self-esteem (OBSE) at the individual level and relationship conflict at the team level-that channel the independent and interactive effects of individual- and team-level abuse onto team members' voice, team-role performance, and turnover intentions. RESULTS from a field study and a scenario study provided support for these multilevel pathways. We conclude that abusive supervision in team settings holds toxic consequences for the team and individual, and offer practical implications as well as suggestions for future research on abusive supervision as a multilevel phenomenon. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2014 APA, all rights reserved).

Deservingness and emotions: Applying the structural model of deservingness to the analysis of affective reactions to outcomes

DOI:10.1080/10463280600662321

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This chapter describes how a structural model of deservingness governed by a principle of balance may be applied to the analysis of emotions relating to deserved or undeserved outcomes of other or of self. In each case perceived deservingness/undeservingness is assumed to mediate both general emotional reactions such as pleasure and dissatisfaction and discrete emotions such as sympathy, resentment, disappointment, and guilt, depending on outcome (positive, negative), the evaluative structure of action/outcome relations, and whether outcomes relate to other or to self. Evidence from studies of reactions to success or failure, and reactions to penalties for offences, supports the analysis, as does earlier research on tall poppies or high achievers. The theoretical analysis is then related to the wider psychological literature on justice and emotions, especially to appraisal theory as exemplified in Weiner's approach. Also discussed are issues concerned with reciprocal relations between affect and deservingness, thoughtful versus automatic processing, new extensions of balance theory, and variables such as like/dislike relations, ingroup/outgroup relations, and perceived responsibility that would moderate perceived deservingness/undeservingness, thereby influencing the emotions that are assumed to be activated in each case.

The effects of organizational changes on employee commitment: A multilevel investigation

DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00852.x

URL

Organizations are concerned with the impact organizational change can have on both individuals' response to the change itself and their ongoing relationship with the organization. This study investigated how organizational changes in 32 different organizations (public and private) affected individuals' commitment to the specific change and their broader commitment to the organization. The results indicate that both types of commitment may be best understood in terms of a 3-way interaction between the overall favorableness (positive/negative) of the change for the work unit members, the extent of the change in the work unit, and the impact of the change on the individual's job. In addition, the fairness of the change process was found to interact with the effects of work unit change on organizational commitment. The implications of these results for future research and practice are discussed.

Third-party punishment and social norms

Strong reciprocity, human cooperation, and the enforcement of social norms

A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation

DOI:10.1162/003355399556151

URL

[本文引用: 1]

"There is strong evidence that people exploit their bargaining power in competitive markets but not in bilateral bargaining situations. There is also strong evidence that people exploit free-riding opportunities in voluntary cooperation games. Yet, when they are given the opportunity to punish free riders, stable cooperation is maintained although punishment is costly for those who punish. This paper asks whether there is a simple common principle that can explain this puzzling evidence. We show that if a fraction of the people exhibits inequality aversion the puzzles can be resolved."

Fairness as deonance

In S. W. Gilliland, D. D. Steiner, & D. P. Skarlicki (Eds.),

Fairness theory: Justice as accountability In J Greenberg & R Cropanzano (Eds), Advances in organization justice (pp 1-55) Stanford University Press Justice as accountability

In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organization justice (pp.

Approach and avoidance motives and close relationships

DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00405.x

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Despite the fact that humans have a deep motivation to pursue and maintain close relationships, little research has examined social relationships from a motivational perspective. In the current paper, we argue that any model of close relationships must simultaneously account for people’s tendencies to both approach incentives and avoid threats in close relationships. To that end, we review research stemming from Gable’s (2006) social and relationship model of motivation on both the antecedents and the consequences of approach and avoidance goal pursuit in the context of close relationships. We conclude with recommendations for future research in this area.

Emotional consequences of categorizing victims of negative outgroup behavior as ingroup or outgroup

DOI:10.1177/1368430201004004002

URL

[本文引用: 5]

This research examined whether people experience anger after perceiving intentional and unfair behavior of an outgroup which has negative consequences for others, but not for themselves. It was predicted that such outgroup behavior causes anger in the observer. dependent on the categorization of the victims as part of its own group or as part of another group. Participants were primed with information that made either differences or similarities between them and the vic tims salient, after which they were confronted with negative behavior of an outgroup. Results confirmed the prediction that the same inform ation concerning unfair and intentional behavior of an outgroup harming others led to more anger in the observed when the victims were perceived as ingroup rather than outgroup. Moreover, anxiery was not affected by perceptron of victims as part of the ingroup or outgroup, saggesting that specific emotions rather than just negative affect were influenced.

Emotional reactions to harmful intergroup behavior

DOI:10.1002/ejsp.296

URL

[本文引用: 5]

In this paper, we examined reactions to situations in which, although one is not personally involved, one could see oneself connected to either the perpetrators or the victims of unfair behavior. We manipulated participants' similarity and measured their identification to either one of two groups which participants later learned was the victim or the perpetrator of harmful behavior. As predicted, making salient similarities to the victims lead participants to: 1) appraise the perpetrator's behavior as more unfair; 2) experience more anger; and 3) be more likely to take action against it and less prone to show support for it as a function of their level of identification with their salient ingroup. In sharp contrast, focusing participants' attention on their similarities to the perpetrators reversed this pattern of findings: Compared to high identifiers, low identifiers appraised the behavior as more unfair than high identifiers, which made them feel angry (and guilty) and less likely to show support for the perpetrator's behavior. The data also provide strong support for a mediational model in which appraisal of the situation colors the emotional reaction which in turn orients action tendencies. We discuss the implications of our findings for the issue of group-based emotions. Copyright 2006 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Costly third-party interventions: The role of incidental anger and attention focus in punishment of the perpetrator and compensation of the victim

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2016.04.004

URL

[本文引用: 1]

61Costly third-party interventions are unlikely to be motivated by self-interest.61Effects of incidental anger and attention focus on third-party interventions were investigated.61Participants induced to anger punished significantly more and compensated less.61However, third parties induced to empathic anger compensated significantly more.61Incidental anger only affected punishment or compensation when attention was sustained.

Patterns of organizational injustice: A taxonomy of what employees regard as unjust

Witnessing wrongdoing: The effects of observer power on incivility intervention in the workplace

DOI:10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.07.006

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Research often paints a dark portrait of power. Previous work underscores the links between power and self-interested, antisocial behavior. In this paper, we identify a potential bright side to power amely, that the powerful are more likely to intervene when they witness workplace incivility. In experimental (Studies 1 and 3) and field (Study 2) settings, we find evidence suggesting that power can shape how, why, and when the powerful respond to observed incivility against others. We begin by drawing on research linking power and action orientation. In Study 1, we demonstrate that the powerful respond with agency to witnessed incivility. They are more likely to directly confront perpetrators, and less likely to avoid the perpetrator and offer social support to targets. We explain the motivation that leads the powerful to act by integrating theory on responsibility construals of power and hierarchy maintenance. Study 2 shows that felt responsibility mediates the effect of power on increased confrontation and decreased avoidance. Study 3 demonstrates that incivility leads the powerful to perceive a status challenge, which then triggers feelings of responsibility. In Studies 2 and 3, we also reveal an interesting nuance to the effect of power on supporting the target. While the powerful support targets less as a direct effect, we reveal countervailing indirect effects: To the extent that incivility is seen as a status challenge and triggers felt responsibility, power indirectly increases support toward the target. Together, these results enrich the literature on third-party intervention and incivility, showing how power may free bystanders to intervene in response to observed incivility.

The Actor and the Observer: Divergent Perceptions of Their Behavior New York: General Learning Press Divergent Perceptions of Their Behavior

The integration of others' experiences in organizational justice judgments

DOI:10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00035-3

URL

[本文引用: 3]

This research examines how people integrate social reports regarding another person's injustice experience into their own justice assessments. Specifically, we examine three variables—participant injustice experience, co-worker injustice severity, and prior contact with co-worker's supervisor—that influence the degree to which individuals express victim empathy (acceptance of the other's injustice report) and victim derogation (assigning at least some blame to the victim) when a co-worker reports an injustice experience. We hypothesized that personal experiences with injustice would facilitate victim empathy and that the severity of a co-worker's injustice report would simultaneously lead to victim empathy and victim derogation. We hypothesized that the effect of prior contact with co-worker supervisor on justice judgments would be moderated by personal experience and the severity of the co-worker's injustice experience. Results from the experiment confirm these predictions.

Schadenfreude: A counter -normative observer response to workplace mistreatment

.

The social construction of injustice: Fairness judgments in response to own and others' unfair treatment by authorities

DOI:10.1006/obhd.1998.2785

URL

PMID:9719655

[本文引用: 3]

The research literature in organizational justice has examined in some detail the dynamics and consequences of justice judgments based on direct experiences with fair and unfair authorities, but little is known about how people form justice judgments on the basis of reports of injustice by others or how group discussion changes justice judgments. The present study examined the consequences of distributed injustice, in which all members of a group experience some denial of voice, and concentrated injustice, in which one member experiences repeated denial of voice and others do not. It was predicted and found that mild personal experiences of injustice are a more potent source of group impressions of injustice than are reports of more severe injustice experienced by others. In both conditions, group ratings of unfairness were more extreme than were the mean of individual ratings either before or after discussion.

Punish the perpetrator or compensate the victim? Gain vs. Loss context modulate third-party altruistic behaviors

DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02066

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Third-party punishment and third-party compensation are primary responses to observed norms violations. Previous studies mostly investigated these behaviors in gain rather than loss context, and few study made direct comparison between these two behaviors. We conducted three experiments to investigate third-party punishment and third-party compensation in the gain and loss context. Participants observed two persons playing Dictator Game to share an amount of gain or loss, and the proposer would propose unfair distribution sometimes. In Study 1A, participants should decide whether they wanted to punish proposer. In Study 1B, participants decided to compensate the recipient or to do nothing. This two experiments explored how gain and loss contexts might affect the willingness to altruistically punish a perpetrator, or to compensate a victim of unfairness. Results suggested that both third-party punishment and compensation were stronger in the loss context. Study 2 directly compare third-party punishment and third-party compensation in the both contexts, by allowing participants choosing between punishment, compensation and keeping. Participants chose compensation more often than punishment in the loss context, and chose more punishments in the gain context. Empathic concern partly explained between-context differences of altruistic compensation and punishment. Our findings provide insights on modulating effect of context on third-party altruistic decisions.

Individual differences in third- party interventions: How justice sensitivity shapes altruistic punishment

DOI:10.1111/j.1750-4716.2011.00084.x

URL

[本文引用: 4]

Altruistic punishment refers to the phenomenon that humans invest their own resources to redress norm violations without self-interest involved. We address the question of who will intervene in situations that allow for altruistic punishment. We suggest that individual differences in a genuine concern for justice, as reflected by the personality trait of justice sensitivity, determine the experience of moral emotions in the face of injustice, which in turn trigger altruistic punishment. Results of two studies support the proposed mediation effect for other-regarding justice sensitivity, even though an opportunity for compensation of the victim (Study 2) was offered as an alternative to punishment (Study 1). Furthermore, the mediation effect was observed when moral outrage was measured by means of quantified open statements (Study 1) and self-report scales using discrete emotions (Study 2). The findings help to explain the psychological mechanisms underlying engagement in costly social sanctioning of norm violations.

Punitive versus compensatory reactions to injustice: Emotional antecedents to third-party interventions

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.10.004

URL

[本文引用: 2]

The almost exclusive focus on punishment and inattention to compensatory alternatives in studies involving experimental games may yield patterns that do not accurately reflect how and when people respond to injustice, particularly if punishment and compensation are not psychologically equivalent approaches to justice restoration. In the current study, we examined participants' preference for punitive and compensatory actions, while also exploring emotional determinants and boundary conditions. Our results indicated that participants actually compensated victims more than they punished offenders and that the majority of participants assigned both. Furthermore, although both interventions were associated with emotional experiences of moral outrage toward the offender, self-focused emotions reflecting feelings of threat only predicted compensation and only when victims were aware that they had been victimized. These findings augment our understanding of third-party interventions, emphasizing the importance of considering response alternatives when studying the psychology of justice.

Third parties’ reactions to the abusive supervision of coworkers

DOI:10.1037/apl0000002

URL

PMID:25243999

[本文引用: 5]

This research examines 3rd parties' reactions to the abusive supervision of a coworker. Reactions were theorized to depend on 3rd parties' beliefs about the targeted coworker and, specifically, whether the target of abuse was considered deserving of mistreatment. We predicted that 3rd parties would experience anger when targets of abuse were considered undeserving of mistreatment; angered 3rd parties would then be motivated to harm the abusive supervisor and support the targeted coworker. Conversely, we predicted that 3rd parties would experience contentment when targets of abuse were considered deserving of mistreatment; contented 3rd parties would then be motivated to exclude the targeted coworker. Additionally, we predicted that 3rd parties' moral identity would moderate the effects of 3rd parties' experienced emotions on their behavioral reactions, such that a strong moral identity would strengthen ethical behavior (i.e., coworker support) and weaken harmful behavior (i.e., supervisor-directed deviance, coworker exclusion). Moderated mediation results supported the predictions. Implications for theory and practice are discussed.

Event system theory: An event-oriented approach to the organizational sciences

DOI:10.5465/amr.2012.0099

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Organizations are dynamic, hierarchically structured entities. Such dynamism is reflected in the emergence of significant events at every organizational level. Despite this fact, there has been relatively little discussion about how events become meaningful and come to impact organizations across space and time. We address this gap by developing event system theory, which suggests that events become salient when they are novel, disruptive, and critical (reflecting an event's strength). Importantly, events can originate at any hierarchical level and their effects can remain within that level or travel up or down throughout the organization, changing or creating new behaviors, features, and events. This impact can extend over time as events vary in duration and timing or as event strength evolves. Event system theory provides a needed shift in focus for organizational theory and research by developing specific propositions articulating the interplay among event strength and the spatial and temporal processes through which events come to influence organizations.

The social effects of punishment events: The influence of violator past performance record and severity of the punishment on observers' justice perceptions and attitudes

Beyond retribution: Conceptualizing restorative justice and exploring its determinants

DOI:10.1007/s11211-009-0092-5

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Previous research considering reactions to injustice has focused predominantly on retributive (i.e., punitive) responses. Restorative justice , a relatively understudied concept, suggests an alternative justice response which emphasizes bilateral discussion in an attempt to reach a consensus about the meaning of the offense and how to address the transgression. The current research explores the additional contribution of restorative justice processes, examining the extent to which bilateral consensus is viewed as a fairer response to transgressions than unilateral decisions. Results show that, independent of the punishment, restorative responses are generally regarded as fairer than nonrestorative responses. And compared to punishment, which tends to be moderated by offender intent and seriousness of the harm, restorative responses are regarded as particularly fair when the involved parties share an identity. Findings suggest the importance of distinguishing retributive justice from a “restorative notion of justice”—a notion that focuses on addressing concerns over the maintenance of existing social relationships and identity-defining values.

Retribution and restoration as general orientations towards justice

DOI:10.1002/per.831

URL

[本文引用: 3]

We proposed two distinct understandings of what justice means to victims and what its restoration entails that are reflected in individual-level justice orientations. Individuals with a retributive orientation conceptualize justice as the unilateral imposition of just deserts against the offender. In contrast, individuals with a restorative orientation conceptualize justice as achieving a renewed consensus about the shared values violated by the offence. Three studies showed differential relations between these two justice orientations and various individual-level values/ideologies and predicted unique variance in preferences for concrete justice-restoring interventions, judicial processes and abstract justice restoration goals. The pattern of results lends validity to the understanding of justice as two distinct conceptualizations, a distinction that provides much needed explanation for divergent preferences for injustice responses. Copyright 2011 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

A model of third parties' morally motivated responses to mistreatment in organizations

DOI:10.5465/AMR.2011.61031810

URL

[本文引用: 6]

ABSTRACT We present a theory of why some people who witness or learn about acts of mistreatment against others in organizations are more likely to recognize this injustice and become personally involved. Drawing from theories of moral identity, moral intuitions, and self-regulation, we explain third parties' morally motivated responses to mistreatment and consider the role of power and belief in the disciplinary system in this process. We discuss implications of the theory and propose future research directions.

The lives of others: Third parties’ responses to others’ injustice

DOI:10.1037/apl0000040

URL

PMID:26214088

[本文引用: 7]

This research takes a moral perspective to studying third parties' reactions to injustice as a function of their moral identity. The authors argue that because third parties with a strong moral identity are more concerned about the welfare of others, they will react more strongly to justice violations than third parties with a comparatively weak moral identity. Furthermore, because interpersonal justice violations are more unambiguously morally wrong compared to distributive and procedural justice violations, the authors propose that third party moral reactions are stronger in response to interpersonal than distributive and procedural justice violations. Results from three studies support these predictions, and show that the third party's moral anger mediates these reactions.

Overlooked but not untouched: How rudeness reduces onlookers’ performance on routine and creative tasks

DOI:10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.01.003

URL

[本文引用: 2]

In three experimental studies, we found that witnessing rudeness enacted by an authority figure (Studies 1 and 3) and a peer (Study 2) reduced observers performance on routine tasks as well as creative tasks. In all three studies we also found that witnessing rudeness decreased citizenship behaviors and increased dysfunctional ideation. Negative affect mediated the relationships between witnessing rudeness and performance. The results of Study 3 show that competition with the victim over scarce resources moderated the relationship between observing rudeness and performance. Witnesses that were in a competition with the victim felt less negative affect in observing his mistreatment and their performance decreased to a lesser extent than observers of rudeness enacted against a non-competitive victim. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Extending the deontic model of justice: Moral self-regulation in third-party responses to injustice

The deontic model of justice and ethical behavior proposes that people care about justice simply for the sake of justice. This is an important consideration for business ethics because it implies that justice and ethical behavior are naturally occurring phenomena independent of system controls or individual self-interest. To date, research on the deontic model and third-party reactions to injustice has focused primarily on individuals’ tendency topunishtransgressors. This research has revealed that witnesses to injustice will consider sacrificing their own resources if it is the only way to sanction an observed transgressor. In this paper we seek to extend this model by arguing that punishment may not be the only “deontic” reaction, and that in fact, third-party observers of injustice may engage in moral self-regulation that would lead them to conclude that the most ethical response is to do nothing. We provide preliminary evidence for our propositions using voiced cognitions data collected during a resource allocation task. Results indicate that deonance may be more complex than originally thought, and previous tests of the model conservative in nature.

Intergroup bias in third-party punishment stems from both ingroup favoritism and outgroup discrimination

DOI:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.12.006

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Social norms pervade almost every aspect of social interaction. If they are violated, not only legal institutions, but other members of society as well, punish, i.e., inflict costs on the wrongdoer. Sanctioning occurs even when the punishers themselves were not harmed directly and even when it is costly for them. There is evidence for intergroup bias in this third-party punishment: third-parties, who share group membership with victims, punish outgroup perpetrators more harshly than ingroup perpetrators. However, it is unknown whether a discriminatory treatment of outgroup perpetrators (outgroup discrimination) or a preferential treatment of ingroup perpetrators (ingroup favoritism) drives this bias. To answer this question, the punishment of outgroup and ingroup perpetrators must be compared to a baseline, i.e., unaffiliated perpetrators. By applying a costly punishment game, we found stronger punishment of outgroup versus unaffiliated perpetrators and weaker punishment of ingroup versus unaffiliated perpetrators. This demonstrates that both ingroup favoritism and outgroup discrimination drive intergroup bias in third-party punishment of perpetrators that belong to distinct social groups.

The justice of need and the activation of humanitarian norms

DOI:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1975.tb00999.x

URL

[本文引用: 2]

The distinctiveness of the justice of need and of humanitarian norms is examined and it is suggested that people do indeed sacrifice their own resources for the benefit of others without hope of external reward, motivated by internalized personal norms. A theoretical process leading from awareness of need through norm activation to overt behavior based on the justice of need is outlined, situational and personality determinants of the activation of personal humanitarian norms and of efforts to neutralize these norms and deflect the moral costs of violating them are explored, and the relationship between humanitarian and exchange norms is discussed.

Third-party reactions to employee (mis) treatment: A justice perspective

DOI:10.1016/S0191-3085(04)26005-1

URL

[本文引用: 16]

To date, theory and research on organizational justice has tended to focus on the victim’s (i.e. the employee’s) perspective; the third party’s perspective has received relatively little systematic attention. In this chapter we develop a model describing how third parties make fairness judgments about an employee’s (mis)treatment by an organization or its agents (including supervisors and peers). Our model also identifies factors that can predict whether third parties will act on their unfairness perceptions. We identify several distinctions between the victim’s and third party’s perspectives. We conclude by explaining how the third party’s perspective offers numerous opportunities and challenges for research.

The third-party perspective of (in)justice

In R. S. Cropanzano & M. L. Ambrose (Eds.), Oxford handbook of justice in work organizations (pp.

Dual processing and organizational justice: The role of rational versus experiential processing in third-party reactions to workplace mistreatment

DOI:10.1037/a0020468

URL

PMID:20836589

[本文引用: 6]

The moral perspective of justice proposes that when confronted by another person's mistreatment, third parties can experience a deontic response, that is, an evolutionary-based emotional reaction that motivates them to engage in retribution toward the transgressor. In this article, we tested whether the third party's deontic reaction is less strong when a rational (vs. experiential) processing frame is primed. Further, we tested whether third parties high (vs. low) in moral identity are more resistant to the effects of processing frames. Results from a sample of 185 French managers revealed that following an injustice, managers primed to use rational processing reported lower retribution tendencies compared with managers primed to use experiential processing. Third parties high in moral identity, however, were less affected by the framing; they reported a high retribution response regardless of processing frame. Theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Organizational injustice: Third parties' reactions to mistreatment of employee

DOI:10.7334/psicothema2012.237

URL

PMID:23628536

[本文引用: 10]

Background: Research on organizational injustice has mainly focused on the victim's perspective. This study attempts to contribute to our understanding of third parties' perspective by empirically testing a model that describes third party reactions to mistreatment of employees. Method: Data were obtained from a sample (N = 334) of Spanish employees from various organizations, nested into 66 work-groups, via a survey regarding their perceptions of organizational mistreatment. Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the data. Results: The proposed model had a limited fit to the data and it was re-specified. Organizational mistreatment, employee performance, and employee organizational commitment explained internal attributions blaming the organization. Moreover, coworkers' organizational identification showed a positive impact on external attributions of responsibility. Lastly, supportive organizational climate and internal attributions accounted for a large percentage of variance in coworkers' perceptions of organizational unfairness. Conclusions: The final model explains the perceptions of injustice on the basis of internal attributions of responsibility in the face of organizational mistreatment of employees.

A relational model of authority in groups

DOI:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60283-X

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This chapter focuses on one particular aspect of authoritativeness: voluntary compliance with the decisions of authorities. Social psychologists have long distinguished between obedience that is the result of coercion, and obedience that is the result of internal attitudes. Opinions describe “reward power” and “coercive power”, in which obedience is contingent on positive and negative outcomes, and distinguish both of these types of power from legitimate power, in which obedience flows from judgments about the legitimacy of the authority. Legitimate power depends on people taking the obligation on themselves to obey and voluntarily follow the decisions made by authorities. The chapter also focuses on legitimacy because it is important to recognize, that legitimacy is not the only attitudinal factor influencing effectiveness. It is also influenced by other cognitions about the authority, most notably judgments of his or her expertise with respect to the problem at hand. The willingness of group members to accept a leader's directives is only helpful when the leader knows what directives to issue.

Observer reactions to interpersonal injustice: The roles of perpetrator intent and victim perception

DOI:10.1002/job.1801

URL

[本文引用: 4]

The present research contributes to a growing literature on observer reactions to injustice experienced by others. In particular, we separated two variables that have previously been confounded in prior research, namely perpetrator intent to cause harm and victim perception of harm. We expected that injustice intent and injustice perceptions would have both unique and joint effects on observer reactions. The results of three experiments in which we manipulated perpetrator injustice intent and victim injustice perceptions supported our predictions. First, we found that observers had more negative reactions toward superiors who intended to inflict high versus low levels of interpersonal injustice toward a subordinate. Second, the injustice intent of the superior influenced observers' reactions more than did victim perceptions of injustice. Third, most novel, we found that the mere intent to cause injustice generated negative reactions in observers, even in the absence of a “true” victim—that is, when the subordinate perceptions of injustice were low. Together, our results emphasize the importance of examining observers' reactions to injustice and incorporating perpetrator intentions into the study of organizational justice. Copyright 08 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Retributive versus compensatory justice: Observers' preference for punishing in response to criminal offenses

DOI:10.1002/ejsp.611

URL

[本文引用: 1]

In the current paper, the author examines whether independent observers of criminal offenses have a relative preference for either retributive justice (i.e., punishing the offender) or compensatory justice (i.e., compensating the victim for the harm done). In Study 1, results revealed that participants recommended higher sums of money if a financial transaction was framed as offender punishment (i.e., the offender would pay money to the victim) than if it was framed as victim compensation (i.e., the victim would receive money from the offender). In Study 2, participants were asked to gather information about court trials following three severe offenses to evaluate whether justice had been done in these cases. Results revealed that participants gathered more information about offender punishment than about victim compensation. In Study 3 these findings were extended by investigating whether observers' relative preference for punishing is moderated by emotional proximity to the victim. Results revealed that the relative preference for punishing only occurred among participants who did not experience emotional proximity to the victim. It is concluded that observers prefer retributive over compensatory justice, provided that they do not feel emotionally close to the victim. Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states

DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.465

URL

PMID:6393179

[本文引用: 2]

Abstract A number of apparently diverse personality scales––variously assessing trait anxiety, neuroticism, ego strength, general maladjustment, repression-sensitization, and social desirability––are reviewed and are shown to be in fact measures of the same stable and pervasive trait. An integrative interpretation of the construct as Negative Affectivity (NA) is presented. A review of studies using measures such as the Beck Depression Inventory, Eysenck Personality Inventory, and Multiple Affect Adjective Check List indicate that high-NA Ss are more likely to experience discomfort at all times and across situations, even in the absence of overt stress. They are relatively more introspective and tend differentially to dwell on the negative side of themselves and the world. Further research is needed to explain the origins of NA and to elucidate the characteristics of low-NA individuals. (505 p ref)

Justice through consensus: Shared identity and the preference for a restorative notion of justice

DOI:10.1002/ejsp.657

URL

[本文引用: 1]

We propose a concept of restorative justice as a sense of justice deriving from consensus about, and the reaffirmation of, values violated by an offence (in contrast to punishment-based retributive justice). Victims should be more likely to seek restorative justice (and less likely retributive justice) when they perceive to share a relevant identity with the offender. In Study 1, when the relevant identity (university affiliation) shared with the offender was made salient (vs. not), participants found a consensus-based response more justice-restoring. In Study 2, when the group (company) shared with the offender was cohesive (vs. not), participants more strongly endorsed a restorative justice philosophy and, mediated by this, responded in consensus-restoring ways. In Study 3, when the offender was an ingroup (vs. outgroup) member, participants more strongly endorsed a restorative justice philosophy, fully mediated by sadness emotions. Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Third party responses to justice failure: An identity-based meaning maintenance model