CN 11-4766/R

主办:中国科学院心理研究所

出版:科学出版社

心理科学进展 ›› 2022, Vol. 30 ›› Issue (12): 2746-2763.doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2022.02746 cstr: 32111.14.2022.02746

收稿日期:2021-09-29

出版日期:2022-12-15

发布日期:2022-09-23

基金资助:

YE Liqun, TAN Xin, YAO Kun, DING Yulong( )

)

Received:2021-09-29

Online:2022-12-15

Published:2022-09-23

摘要:

选择性注意能够作用于视觉信息加工的不同阶段。各个注意阶段均受到老化过程的影响, 其中注意早期阶段的老化研究对于理解认知老化的发生机制有重要意义。本文系统地梳理了刺激前的注意预期阶段以及刺激后200 ms内的早期感知注意阶段的正常老年人和青年人ERP比较研究, 以探讨正常老化对视觉早期注意的影响。现有证据表明, 相对于青年人, 正常老年人:(1)多个早期ERP注意效应(包括注意预期ADAN, 早期空间注意N1, 以及特征注意SP和SN)在潜伏期上都存在显著延迟; (2)在振幅上, 不同ERP注意效应的老化表现存在差异:某些ERP成分(包括注意预期EDAN, 以及早期空间注意P1)的注意效应没有明显减弱, 而某些ERP成分(包括注意预期alpha, 早期空间注意N1, 以及特征注意SN)的注意效应受到老化调控; (3)一些注意效应(包括特征注意SP成分, 以及客体注意P1和N1成分)的目标增强机制保留, 而干扰抑制机制缺损。目前已有研究在老化对注意效应振幅的调控上还存在不一致, 这可能与研究的信噪比、任务难度、注意机制分离以及老年人的个体差异有关。未来研究应考虑这些因素以更好地探究正常老化对视觉早期注意的影响。

中图分类号:

叶丽群, 谭欣, 姚堃, 丁玉珑. (2022). 正常老化对视觉早期注意的影响——来自ERP的证据. 心理科学进展 , 30(12), 2746-2763.

YE Liqun, TAN Xin, YAO Kun, DING Yulong. (2022). Influence of normal aging on early stages of visual attention: Evidence from ERP studies. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(12), 2746-2763.

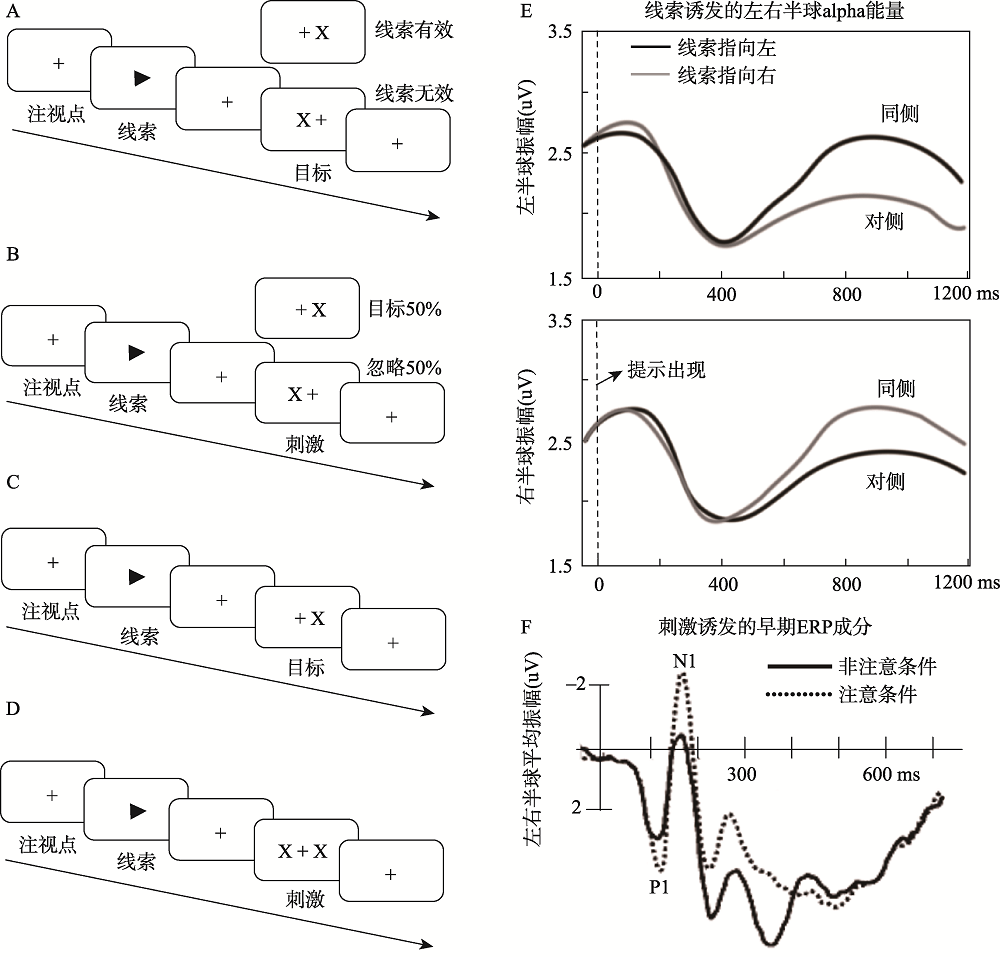

图1 空间线索范式及青年人研究的经典结果。 (A) 概率性空间线索范式, 图中呈现了提示有效试次(目标大概率出现在提示侧, 例如70~80%)和提示无效试次(目标小概率出现非提示侧, 例如20~30%), 被试要对随机出现在左视野或右视野的目标刺激进行反应; (B) 指示性空间线索范式1, 刺激等概率出现在线索提示侧或非提示侧。被试只对出现在提示侧的刺激进行反应, 对出现在非提示侧的刺激不进行反应; (C)指示性空间线索范式2, 刺激只出现在线索提示侧, 即只要刺激出现, 被试都要对其进行反应; (D) 指示性空间线索范式3, 在提示与非提示侧同时都出现刺激, 被试只需对提示侧的刺激反应, 同时忽略非提示侧的刺激; (E) 注意预期alpha偏侧化的青年人经典结果, 提示位置对侧半球的alpha活动能量比同侧更弱; 资料来源:修改自“Anticipatory biasing of visuospatial attention indexed by retinotopically specific α-bank electroencephalography increases over occipital cortex. ” by M. S. Worden, J. J. Foxe, N. Wang and G. V. Simpson. (2000). Journal of Neuroscience, 20(6), 3. (F) 内源性空间线索范式下的青年人经典ERP结果, 图中波形为刺激诱发的ERP活动, 注意条件下的P1和N1振幅比非注意条件更大。资料来源:修改自“Modulations of sensory-evoked brain potentials indicate changes in perceptual processing during visual-spatial priming. ” by G. R. Mangun and S. A. Hillyard (1991). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 17(4), 1060.

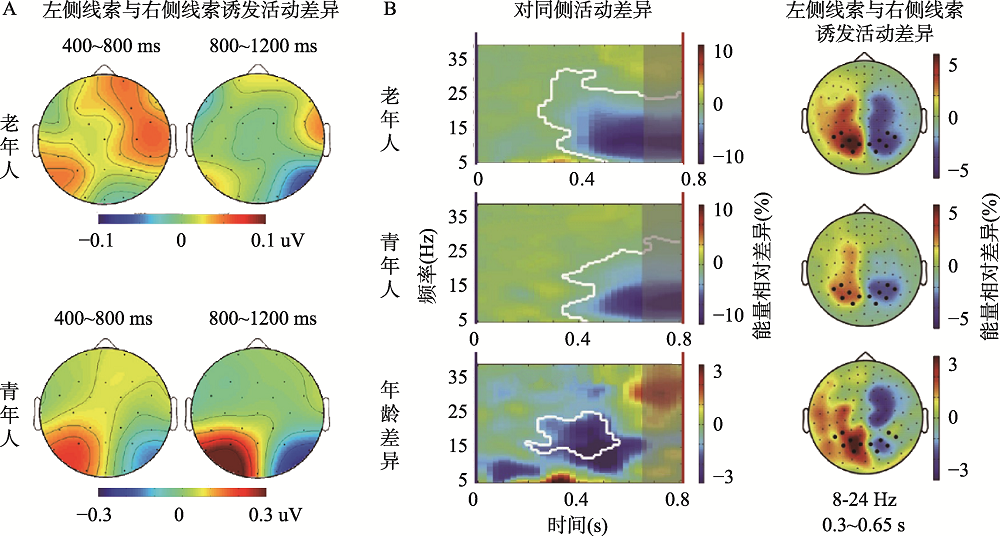

图2 空间注意预期alpha偏侧化的老化研究结果。 (A) 图为提示左右侧alpha活动能量差异的地形图, 从图中可以看到无论是在400~800 ms还是在800~1200 ms的时间窗(以线索出现为零时刻点), 青年人均有明显的alpha偏侧化活动, 老年人则没有。资料来源:修改自“Normal aging selectively diminishes alpha lateralization in visual spatial attention. ” by X. Hong, J. Sun, J. J. Bengson, G. R. Mangun, and S. Tong. (2015). NeuroImage, 106, 359. (B)左图为对同侧神经振荡活动差异的时频分析图, 对侧指的是非提示侧, 同侧指的是提示侧, 零时刻点为线索出现时间, 红线为目标刺激出现时间, 图中白圈指该时频区域的活动达到统计显著。右图为提示左右侧神经振荡活动能量差异的地形图, 时间窗为线索出现后300~650 ms, 分析频率为8~24 Hz。由上至下分别为老年人、青年人以及老年人与青年人差异的活动。从图中可以看出:老年人有与青年人相似的alpha能量偏侧化活动(8~12 Hz), 且在beta频段(13~24 Hz)上也有偏侧化活动。资料来源:修改自“Anticipatory neural dynamics of spatial-temporal orienting of attention in younger and older adults. ” by S. G. Heideman, G. Rohenkohl, J. J. Chauvin, C. E. Palmer, F. van Ede, and A. C. Nobre. (2018). NeuroImage, 178, 49.

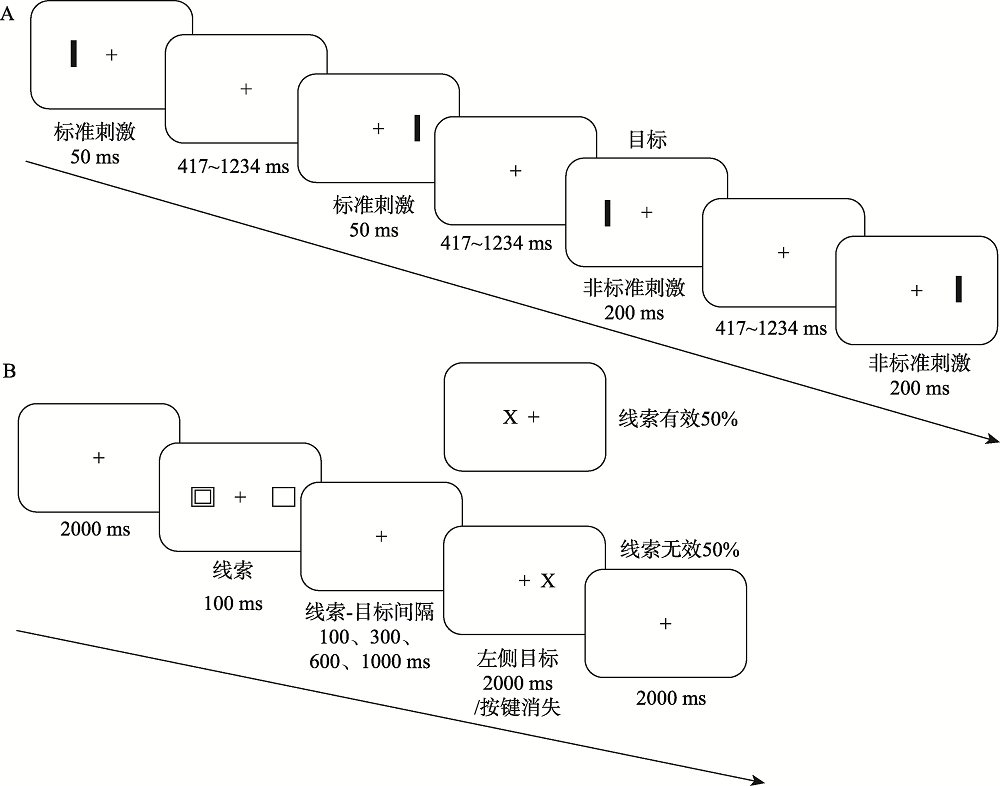

图3 空间注意研究的范式和老年人ERP结果。 (A) 持续性空间注意范式。被试盯住中央注视点, 保持视线不要偏离, 并始终注意某一侧视野的刺激(图中举例为左侧)。在每个试次中, 注视点的左侧或右侧会随机呈现一个时间为50 ms的矩形条 (标准刺激)或时间为200 ms的矩形条 (非标准刺激), 被试只需在非标准刺激出现在注意侧时按键反应。为了排除刺激物理属性和反应诱发活动的影响, 一般分析标准刺激(无需按键)在特定位置上诱发的ERP活动。被试的注意侧与该刺激的空间位置一致时是注意条件, 不一致时是非注意条件。资料来源:修改自“Selective attention to spatial and non-spatial visual stimuli is affected differentially by age: Effects on event-related brain potentials and performance data. ” by D. Talsma, A. Kok, and K. R. Ridderinkhof (2006). International Journal of Psychophysiology, 62(2), 251-252. (B)外源性空间线索范式, 被试盯住中央注视点, 保持视线不要偏离。注视点左右两侧的方格中, 其中一个会突然闪烁(线索), 吸引被试注意。随后目标刺激将出现在任意一侧视野中, 目标刺激与线索提示位置一致(有效条件)和不一致(无效条件)的试次各占50%, 即线索没有提示性。被试需要忽略闪烁刺激, 只对目标刺激做反应。

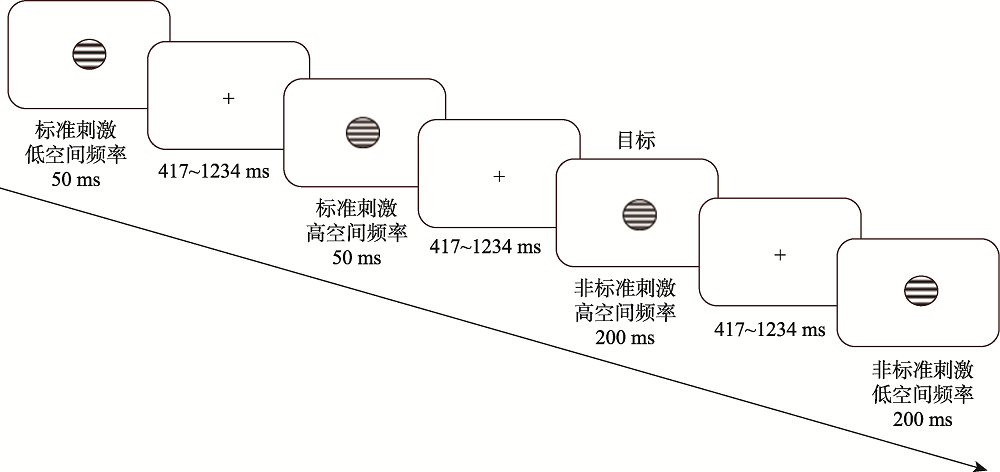

图4 基于空间频率的特征注意任务。 实验连续随机呈现四种刺激:空间频率高(低)且呈现时间长(短)的光栅。任务要求被试在一半组块中注意空间频率高的光栅(如图举例), 在另一半组块中注意空间频率低的光栅, 并在检测到需要注意的频率且呈现时间较长的光栅(非标准刺激)时(如图举例为高空间频率且呈现200 ms)按键反应。在该实验中, 被试无需对呈现时间较短(标准刺激)或非注意空间频率光栅进行反应。资料来源:修改自“Selective attention to spatial and non-spatial visual stimuli is affected differentially by age: Effects on event-related brain potentials and performance data ” by D. Talsma, A. Kok, and K. R. Ridderinkhof (2006). International Journal of Psychophysiology, 62(2), 256-257.

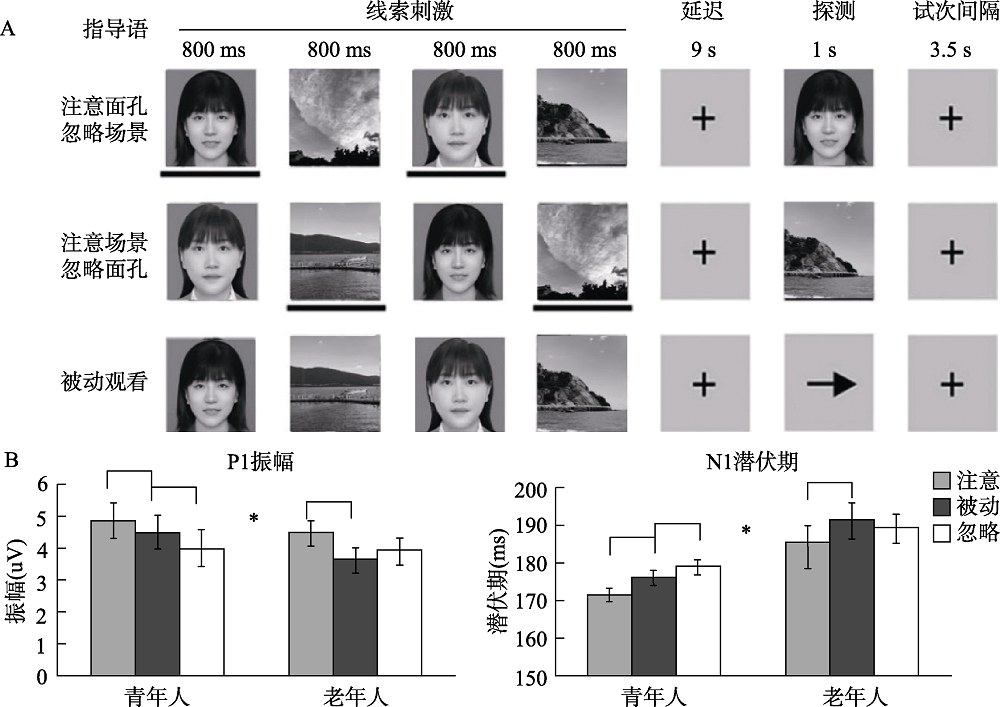

图5 延迟识别工作记忆任务及主要结果。 资料来源:修改自“Age-related top-down suppression deficit in the early stages of cortical visual memory processing, ” by A. Gazzaley, W. Clapp, J. Kelley, K. McEvoy, R. T. Knight and M. D' Esposito (2008). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(35), 13123. (A)任务流程, 屏幕呈现面孔或场景图片, 并在不同的任务条件下要求被试注意特定类别的图片:注意面孔(忽略场景)、注意场景(忽略面孔)以及被动观看。在前两种条件下, 被试需要判断随后呈现的探测图片是否为之前注意过的图片, 而在被动观看条件(中性条件)下, 被试需要判断箭头方向(与图片无关)。刺激下面的线是用来强调任务相关性的, 而在实际的任务中并不存在。(B)图中显示了面孔图片诱发的P1振幅和N1潜伏期的结果, 中括号表明存在显著差异, 例如老年人注意条件的P1振幅显著大于忽略条件。

图6 青年人和老年人的特征注意ERP对比研究的结果。 资料来源:修改自“Age-related differences in enhancement and suppression of neural activity underlying selective attention in matched young and old adults. ” by A. E. Haring, T. Y. Zhuravleva, B. R. Alperin, D. M. Rentz, P. J. Holcomb and K. R. Daffner. (2013). Brain Research, 1499, 74. (A) 标准刺激在注意条件、非注意条件和中性条件下诱发的前额正向ERP活动。SP为注意条件(黑线)比非注意条件(红线)更正的差异活动, 老年人的SP成分潜伏期比青年人更晚。(B) 任意两种条件间的差异波地形图。青年人的SP成分主要来源于中性与非注意条件的差异, 老年人的SP成分主要来源于注意与中性条件的差异。

| [1] |

Allen, H. A., & Payne, H. (2012). Similar behavior, different brain patterns: Age-related changes in neural signatures of ignoring. NeuroImage, 59(4), 4113-4125.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.070 URL |

| [2] | Allon, A. S., & Luria, R. (2019). Filtering performance in visual working memory is improved by reducing early spatial attention to the distractors. Psychophysiology, 56(5), 1-15. |

| [3] |

Alperin, B. R., Haring, A. E., Zhuravleva, T. Y., Holcomb, P. J., Rentz, D. M., & Daffner, K. R. (2013). The dissociation between early and late selection in older adults. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 25(12), 2189-2206.

doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00456 pmid: 23915054 |

| [4] |

Amenedo, E., Gutiérrez-Domínguez, F. J., Mateos-Ruger, S. M., & Pazo-Álvarez, P. (2014). Stimulus-locked and response-locked ERP correlates of spatial inhibition of return (IOR) in old age. Journal of Psychophysiology, 28(3), 105-123.

doi: 10.1027/0269-8803/a000119 URL |

| [5] |

Amenedo, E., Lorenzo-López, L., & Pazo-Álvarez, P. (2012). Response processing during visual search in normal aging: The need for more time to prevent cross talk between spatial attention and manual response selection. Biological Psychology, 91(2), 201-211.

doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.06.004 pmid: 22743592 |

| [6] |

Baluch, F., & Itti, L. (2011). Mechanisms of top-down attention. Trends in Neurosciences, 34(4), 210-224.

doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.02.003 pmid: 21439656 |

| [7] |

Cabeza, R., Albert, M., Belleville, S., Craik, F., Duarte, A., Grady, C. L., ... Rajah, M. N. (2018). Maintenance, reserve and compensation: The cognitive neuroscience of healthy ageing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 19(11), 701-710.

doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0068-2 pmid: 30305711 |

| [8] | Castel, A. D., Chasteen, A. L., Scialfa, C. T., & Pratt, J. (2003). Adult age differences in the time course of inhibition of return. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(5), 256-259. |

| [9] |

Curran, T., Hills, A., Patterson, M. B., & Strauss, M. E. (2001). Effects of aging on visuospatial attention: An ERP study. Neuropsychologia, 39(3), 288-301.

pmid: 11163607 |

| [10] |

de Fockert, J. W., Ramchurn, A., van Velzen, J., Bergström, Z., & Bunce, D. (2009). Behavioral and ERP evidence of greater distractor processing in old age. Brain Research, 1282, 67-73.

doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.060 pmid: 19497314 |

| [11] |

Deiber, M. P., Ibañez, V., Missonnier, P., Rodriguez, C., & Giannakopoulos, P. (2013). Age-associated modulations of cerebral oscillatory patterns related to attention control. NeuroImage, 82, 531-546.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.037 URL |

| [12] |

Deiber, M. P., Meziane, H. B., Hasler, R., Rodriguez, C., Toma, S., Ackermann, M., ... Giannakopoulos, P. (2015). Attention and working memory-related EEG markers of subtle cognitive deterioration in healthy elderly individuals. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 47(2), 335-349.

doi: 10.3233/JAD-150111 URL |

| [13] |

di Russo, F., Berchicci, M., Bianco, V., Mussini, E., Perri, R. L., Pitzalis, S., ... Spinelli, D. (2021). Sustained visuospatial attention enhances lateralized anticipatory ERP activity in sensory areas. Brain Structure and Function, 226(2), 457-470.

doi: 10.1007/s00429-020-02192-6 pmid: 33392666 |

| [14] |

di Russo, F., Berchicci, M., Bianco, V., Perri, R. L., Pitzalis, S., & Mussini, E. (2021). Modulation of anticipatory visuospatial attention in sustained and transient tasks. Cortex, 135, 1-9.

doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2020.11.007 pmid: 33341592 |

| [15] |

Ding, Y., Martinez, A., Qu, Z., & Hillyard, S. A. (2014). Earliest stages of visual cortical processing are not modified by attentional load. Human Brain Mapping, 35(7), 3008-3024.

pmid: 25050422 |

| [16] |

Doallo, S., Lorenzo-Lopez, L., Vizoso, C., Holguín, S. R., Amenedo, E., Bará, S., & Cadaveira, F. (2005). Modulations of the visual N1 component of event-related potentials by central and peripheral cueing. Clinical Neurophysiology, 116(4), 807-820.

pmid: 15792890 |

| [17] |

Eimer, M. (1994). "Sensory gating" as a mechanism for visuospatial orienting: Electrophysiological evidence from trial-by-trial cuing experiments. Perception & Psychophysics, 55(6), 667-675.

doi: 10.3758/BF03211681 URL |

| [18] | Eimer, M. (2014). The time course of spatial attention: Insights from event-related brain potentials. In A. C. Nobre & S. Kastner (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Attention (1, pp. 289-317). Oxford Academic. |

| [19] |

Erel, H., & Levy, D. A. (2016). Orienting of visual attention in aging. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 69, 357-380.

doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.010 pmid: 27531234 |

| [20] |

Feldmann, W. T., & Vogel, E. K. (2018). Neural evidence for the contribution of active suppression during working memory filtering. Cerebral Cortex, 29(2), 529-543.

doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx336 URL |

| [21] |

Foster, J. J., & Awh, E. (2019). The role of alpha oscillations in spatial attention: Limited evidence for a suppression account. Current Opinion in Psychology, 29, 34-40.

doi: S2352-250X(18)30168-4 pmid: 30472541 |

| [22] |

Foxe, J. J., & Snyder, A. C. (2011). The role of alpha-band brain oscillations as a sensory suppression mechanism during selective attention. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 154.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00154 pmid: 21779269 |

| [23] | Gaspar, J. M., Christie, G. J., Prime, D. J., Jolicœur, P., & McDonald, J. J. (2016). Inability to suppress salient distractors predicts low visual working memory capacity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 113(13), 3696-3698. |

| [24] |

Gazzaley, A., Clapp, W., Kelley, J., McEvoy, K., Knight, R. T., & D' Esposito, M. (2008). Age-related top-down suppression deficit in the early stages of cortical visual memory processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(35), 13122-13126.

doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806074105 URL |

| [25] |

Geerligs, L., Saliasi, E., Maurits, N. M., & Lorist, M. M. (2012). Compensation through increased functional connectivity: Neural correlates of inhibition in old and young. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24(10), 2057-2069.

doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00270 pmid: 22816367 |

| [26] |

Geerligs, L., Saliasi, E., Maurits, N. M., Renken, R. J., & Lorist, M. M. (2014). Brain mechanisms underlying the effects of aging on different aspects of selective attention. NeuroImage, 91, 52-62.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.029 pmid: 24473095 |

| [27] |

Gould, I. C., Rushworth, M. F., & Nobre, A. C. (2011). Indexing the graded allocation of visuospatial attention using anticipatory alpha oscillations. Journal of Neurophysiology, 105(3), 1318-1326.

doi: 10.1152/jn.00653.2010 pmid: 21228304 |

| [28] | Grady, C. L. (2017). Age differences in functional connectivity at rest and during cognitive tasks. In R. Cabeza, L. Nyberg & D. C. Park (Eds.), Cognitive neuroscience of aging: Linking cognitive and cerebral aging (2nd ed., pp. 105-130). New York, the United States of America: Oxford University Press. |

| [29] |

Guilbert, A., Clément, S., & Moroni, C. (2019). Aging and orienting of visual attention: Emergence of a rightward attentional bias with aging? Developmental Neuropsychology, 44(3), 310-324.

doi: 10.1080/87565641.2019.1605517 pmid: 31001999 |

| [30] |

Haring, A. E., Zhuravleva, T. Y., Alperin, B. R., Rentz, D. M., Holcomb, P. J., & Daffner, K. R. (2013). Age-related differences in enhancement and suppression of neural activity underlying selective attention in matched young and old adults. Brain Research, 1499, 69-79.

doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.01.003 pmid: 23313874 |

| [31] |

Heideman, S. G., Rohenkohl, G., Chauvin, J. J., Palmer, C. E., van Ede, F., & Nobre, A. C. (2018). Anticipatory neural dynamics of spatial-temporal orienting of attention in younger and older adults. NeuroImage, 178, 46-56.

doi: S1053-8119(18)30400-2 pmid: 29733953 |

| [32] |

Hillyard, S. A., & Münte, T. F. (1984). Selective attention to color and location: An analysis with event-related brain potentials. Perception & Psychophysics, 36(2), 185-198.

doi: 10.3758/BF03202679 URL |

| [33] |

Hong, X., Sun, J., Bengson, J. J., Mangun, G. R, & Tong, S. (2015). Normal aging selectively diminishes alpha lateralization in visual spatial attention. NeuroImage, 106, 353-363.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.11.019 pmid: 25463457 |

| [34] |

Hopfinger, J. B., & Mangun, G. R. (1998). Reflexive attention modulates processing of visual stimuli in human extrastriate cortex. Psychological Science, 9(6), 441-447.

pmid: 26321798 |

| [35] | Hopfinger, J. B., & Mangun, G. R. (2001). Tracking the influence of reflexive attention on sensory and cognitive processing. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 1(1), 56-65. |

| [36] |

Kenemans, J. L., Smulders, F. T. Y., & Kok, A. (1995). Selective processing of two-dimensional visual stimuli in young and old subjects: Electrophysiological analysis. Psychophysiology, 32(2), 108-120.

pmid: 7630975 |

| [37] |

Klimesch, W. (2012). Alpha-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(12), 606-617.

doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.10.007 URL |

| [38] |

Lavie, N. (2005). Distracted and confused? Selective attention under load. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 75-82.

doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.004 URL |

| [39] |

Learmonth, G., Benwell, C. S. Y., Thut, G., & Harvey, M. (2017). Age-related reduction of hemispheric lateralization for spatial attention: An EEG study. NeuroImage, 153, 139-151.

doi: S1053-8119(17)30259-8 pmid: 28343987 |

| [40] |

Leenders, M. P., Lozano-Soldevilla, D., Roberts, M. J., Jensen, O., & de Weerd, P. (2018). Diminished alpha lateralization during working memory but not during attentional cueing in older adults. Cerebral Cortex, 28(1), 21-32.

doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw345 URL |

| [41] | Li, T., Wang, L., Huang, W., Zhen, Y., Zhong, C., Qu, Z., & Ding, Y. (2020). Onset time of inhibition of return is a promising index for assessing cognitive functions in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(4), 753-761. |

| [42] |

Lorenzo-López, L., Amenedo, E., & Cadaveira, F. (2008). Feature processing during visual search in normal aging: Electrophysiological evidence. Neurobiology of Aging, 29(7), 1101-1110.

pmid: 17346855 |

| [43] |

Lorenzo-López, L., Doallo, S., Vizoso, C., Amenedo, E., Holguín, S. R., & Cadaveira, F. (2002). Covert orienting of visuospatial attention in the early stages of aging. Neuroreport, 13(11), 1459-1462.

pmid: 12167773 |

| [44] |

Luck, S. J., Hillyard, S. A., Mouloua, M., Woldorff, M. G., Clark, V. P., & Hawkins, H. L. (1994). Effects of spatial cuing on luminance detectability: Psychophysical and electrophysiological evidence for early selection. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 20(4), 887-904.

doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.20.4.887 URL |

| [45] | Luck, S. J., & Kappenman, E. S. (2012). ERP components and selective attention. In S. J. Luck & E. S. Kappenman (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of event-related potential components (pp. 295-327). New York, the United States of America: Oxford University Press. |

| [46] |

Madden, D. J. (2007). Aging and visual attention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 70-74.

doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00478.x pmid: 18080001 |

| [47] | Madden, D. J., & Monge, Z. A. (2019). Visual attention with cognitive aging. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. (pp. 1-40). Oxford University Press. |

| [48] |

Madden, D. J., Spaniol, J., Bucur, B., & Whiting, W. L. (2007). Age-related increase in top-down activation of visual features. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 60(5), 644-651.

doi: 10.1080/17470210601154347 URL |

| [49] |

Mangun, G. R., & Hillyard, S. A. (1987). The spatial allocation of visual attention as indexed by event-related brain potentials. Human Factors, 29(2), 195-211.

pmid: 3610184 |

| [50] |

Mangun, G. R., & Hillyard, S. A. (1988). Spatial gradients of visual attention: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 70(5), 417-428.

pmid: 2460315 |

| [51] |

Mangun, G. R., & Hillyard, S. A. (1991). Modulations of sensory-evoked brain potentials indicate changes in perceptual processing during visual-spatial priming. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 17(4), 1057-1074.

doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.17.4.1057 URL |

| [52] |

Martín-Arévalo, E., Chica, A. B., & Lupiáñez, J. (2015). No single electrophysiological marker for facilitation and inhibition of return: A review. Behavioural Brain Research, 300, 1-10.

doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.11.030 URL |

| [53] |

Mathuranath, P. S., Nestor, P. J., Berrios, G. E., Rakowicz, W., & Hodges, J. R. (2000). A brief cognitive test battery to differentiate Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 55(11), 1613-1620.

pmid: 11113213 |

| [54] |

Mcdonald, J. J., Ward, L. M., & Kiehl, K. A. (1999). An event-related brain potential study of inhibition of return. Perception & Psychophysics, 61(7), 1411-1423.

doi: 10.3758/BF03206190 URL |

| [55] |

Muiños, M., Palmero, F., & Ballesteros, S. (2016). Peripheral vision, perceptual asymmetries and visuospatial attention in young, young-old and oldest-old adults. Experimental Gerontology, 75, 30-36.

doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.12.006 pmid: 26702735 |

| [56] |

Nagamatsu, L. S., Carolan, P., Liu-Ambrose, T. Y. L., & Handy, T. C. (2011). Age-related changes in the attentional control of visual cortex: A selective problem in the left visual hemifield. Neuropsychologia, 49(7), 1670-1678.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.02.040 pmid: 21356222 |

| [57] |

Nagamatsu, L. S., Liu-Ambrose, T. Y. L., Carolan, P., & Handy, T. C. (2009). Are impairments in visual-spatial attention a critical factor for increased falls risk in seniors? An event-related potential study. Neuropsychologia, 47(13), 2749-2755.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.05.022 pmid: 19501605 |

| [58] |

Noonan, M. P., Adamian, N., Pike, A., Printzlau, F., Crittenden, B. M., & Stokes, M. G. (2016). Distinct mechanisms for distractor suppression and target facilitation. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(6), 1797-1807.

doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2133-15.2016 pmid: 26865606 |

| [59] |

Oberauer, K. (2019). Working memory and attention—A conceptual analysis and review. Journal of Cognition, 2(1), 36.

doi: 10.5334/joc.58 pmid: 31517246 |

| [60] |

Olk, B., & Kingstone, A. (2014). Attention and ageing: Measuring effects of involuntary and voluntary orienting in isolation and in combination. British Journal of Psychology, 106(2), 235-252.

doi: 10.1111/bjop.12082 URL |

| [61] |

Rasoulzadeh, V., Sahan, M. I., van Dijck, J. P., Abrahamse, E., Marzecova, A., Verguts, T., & Fias, W. (2021). Spatial attention in serial order working memory: An EEG study. Cerebral Cortex, 31(5), 2482-2493.

doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhaa368 URL |

| [62] |

Sander, M. C., Werkle-Bergner, M., & Lindenberger, U. (2012). Amplitude modulations and inter-trial phase stability of alpha-oscillations differentially reflect working memory constraints across the lifespan. NeuroImage, 59(1), 646-654.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.06.092 pmid: 21763439 |

| [63] |

Satel, J., Hilchey, M. D., Wang, Z., Story, R., & Klein, R. M. (2013). The effects of ignored versus foveated cues upon inhibition of return: An event-related potential study. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 75(1), 29-40.

doi: 10.3758/s13414-012-0381-1 URL |

| [64] |

Schmitz, T. W., Cheng, F. H., & de Rosa, E. (2010). Failing to ignore: Paradoxical neural effects of perceptual load on early attentional selection in normal aging. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(44), 14750-14758.

doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2687-10.2010 pmid: 21048134 |

| [65] |

Schmitz, R., & Peigneux, P. (2011). Age-related changes in visual pseudoneglect. Brain and Cognition, 76(3), 382-389.

doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2011.04.002 pmid: 21536360 |

| [66] |

Sciberras-Lim, E. T., & Lambert, A. J. (2017). Attentional orienting and dorsal visual stream decline: Review of behavioral and EEG Studies. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9, 246.

doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00246 pmid: 28798685 |

| [67] | Serences, J. T., & Kastner, S. (2014). A multi-level account of selective attention. In A. C. Nobre & S. Kastner (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of attention (pp. 76-104). New York, the United States of America: Oxford University Press. |

| [68] |

Talsma, D., Kok, A., & Ridderinkhof, K. R. (2006). Selective attention to spatial and non-spatial visual stimuli is affected differentially by age: Effects on event-related brain potentials and performance data. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 62(2), 249-261.

pmid: 16806547 |

| [69] |

Tian, Y., Klein, R. M., Satel, J., Xu, P., & Yao, D. (2011). Electrophysiological explorations of the cause and effect of inhibition of return in a cue-target paradigm. Brain Topography, 24(2), 164-182.

doi: 10.1007/s10548-011-0172-3 pmid: 21365310 |

| [70] | Tunnermann, J., Petersen, A., & Scharlau, I. (2015). Does attention speed up processing? Decreases and increases of processing rates in visual prior entry. Journal of Vision, 15(3), 1-27. |

| [71] |

Vaden, R. J., Hutcheson, N. L., McCollum, L. A., Kentros, J., & Visscher, K. M. (2012). Older adults, unlike younger adults, do not modulate alpha power to suppress irrelevant information. NeuroImage, 63(3), 1127-1133.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.07.050 pmid: 22885248 |

| [72] |

van der Waal, M., Farquhar, J., Fasotti, L., & Desain, P. (2017). Preserved and attenuated electrophysiological correlates of visual spatial attention in elderly subjects. Behavioural Brain Research, 317, 415-423.

doi: S0166-4328(16)30703-3 pmid: 27678287 |

| [73] |

van Moorselaar, D., & Slagter, H. A. (2019). Learning what is irrelevant or relevant: Expectations facilitate distractor inhibition and target facilitation through distinct neural mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience, 39(35), 6953-6967.

doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0593-19.2019 pmid: 31270162 |

| [74] |

Wang, Y., Fu, S., Greenwood, P., Luo, Y., & Parasuraman, R. (2012). Perceptual load, voluntary attention, and aging: An event-related potential study. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 84(1), 17-25.

doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.01.002 pmid: 22248536 |

| [75] |

Wascher, E., & Tipper, S. P. (2004). Revealing effects of noninformative spatial cues: An EEG study of inhibition of return. Psychophysiology, 41(5), 716-728.

pmid: 15318878 |

| [76] |

Worden, M. S., Foxe, J. J., Wang, N., & Simpson, G. V. (2000). Anticipatory biasing of visuospatial attention indexed by retinotopically specific α-bank electroencephalography increases over occipital cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 20(6), 1-6.

doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00001.2000 URL |

| [77] |

Yamaguchi, S., Tsuchiya, H., & Kobayashi, S. (1995). Electrophysiologic correlates of visuo-spatial attention shift. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology, 94(6), 450-461.

pmid: 7607099 |

| [78] |

Zanto, T. P., Hennigan, K., Östberg, M., Clapp, W. C., & Gazzaley, A. (2010). Predictive knowledge of stimulus relevance does not influence top-down suppression of irrelevant information in older adults. Cortex, 46(4), 564-574.

doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.08.003 pmid: 19744649 |

| [79] |

Zanto, T. P., Toy, B., & Gazzaley, A. (2010). Delays in neural processing during working memory encoding in normal aging. Neuropsychologia, 48(1), 13-25.

doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.08.003 pmid: 19666036 |

| [80] | Zanto, T. P., & Gazzaley, A. (2014). Attention and ageing. In A. C. Nobre & S. Kastner (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of attention (pp. 927-971). New York, the United States of America: Oxford University Press. |

| [81] | Zanto, T. P., & Gazzaley, A. (2017). Selective attention and inhibitory control in the aging brain. In R. Cabeza, L. Nyberg, & D. C. Park (Eds.), Cognitive neuroscience of aging: Linking cognitive and cerebral aging (pp. 207-234). New York, the United States of America: Oxford University Press. |

| [82] |

Zhuravleva, T. Y., Alperin, B. R., Haring, A. E., Rentz, D. M., Holcomb, P. J., & Daffner, K. R. (2014). Age-related decline in bottom-up processing and selective attention in the very old. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 31(3), 261-271.

doi: 10.1097/WNP.0000000000000056 pmid: 24887611 |

| [1] | 陈子龙, 季琭妍. 多面孔情绪变异性的自动化加工:来自视觉失匹配负波的证据[J]. 心理科学进展, 2023, 31(suppl.): 34-34. |

| [2] | 谢莹, 刘昱彤, 陈明亮, 梁安迪. 品牌消费旅程中消费者的认知心理过程——神经营销学视角[J]. 心理科学进展, 2021, 29(11): 2024-2042. |

| [3] | 冉光明, 李睿, 张琪. 高社交焦虑者识别动态情绪面孔的神经机制[J]. 心理科学进展, 2020, 28(12): 1979-1988. |

| [4] | 李萍, 张明明, 李帅霞, 张火垠, 罗文波. 面孔表情和声音情绪信息整合加工的脑机制[J]. 心理科学进展, 2019, 27(7): 1205-1214. |

| [5] | 王霞, 卢家楣, 陈武英. 情绪词加工过程及其情绪效应特点:ERP的证据[J]. 心理科学进展, 2019, 27(11): 1842-1852. |

| [6] | 傅世敏, 陈晓雯, 刘雨琪. 研究争论:空间注意是否调制C1成分?[J]. 心理科学进展, 2018, 26(11): 1901-1914. |

| [7] | 孟泽龙, 赵婧, 毕鸿燕. 汉语发展性阅读障碍儿童的视觉大细胞通路功能探究:一项ERPs研究[J]. 心理科学进展, 2017, 25(suppl.): 2-2. |

| [8] | Xi Jie, Wu-li Jia, Pan Zhang, Chang-bing Huang . PERCEPTUAL LEARNING INCREASES THE SENSORY GAIN OF THE EARLY AND LATE ERP COMPONENT[J]. 心理科学进展, 2017, 25(suppl.): 91-91. |

| [9] | 辛昕;任桂琴;李金彩;唐晓雨. 早期视听整合加工——来自MMN的证据[J]. 心理科学进展, 2017, 25(5): 757-768. |

| [10] | 徐琴芳, 王延培. 脑电测量在儿童发展性障碍诊断中的应用[J]. 心理科学进展, 2017, 25(12): 2136-2144. |

| [11] | 徐晓东;陈庆荣. 汉语焦点信息影响代词回指的电生理机制[J]. 心理科学进展, 2014, 22(6): 902-910. |

| [12] | 张晓露;陈旭. 成人依恋风格在信息加工中表现出差异性的神经机制[J]. 心理科学进展, 2014, 22(3): 448-457. |

| [13] | 张阳阳;饶俪琳;梁竹苑;周媛;李纾. 风险决策过程验证:补偿/非补偿模型之争的新认识与新证据[J]. 心理科学进展, 2014, 22(2): 205-219. |

| [14] | 徐晓东. 一致性关系中的性别范畴特征及其加工机制[J]. 心理科学进展, 2013, 21(10): 1731-1740. |

| [15] | 刘书青;汪海玲;彭凯平;郑先隽;刘在佳;徐胜眉. 注意的跨文化研究及意义[J]. 心理科学进展, 2013, 21(1): 37-47. |

| 阅读次数 | ||||||

|

全文 |

|

|||||

|

摘要 |

|

|||||