1 引言

目光注视在人际交流和情感联结中起着主要作用(Kleinke, 1986)。解码目光注视变化的能力是社会认知发展的基础(Farroni et al., 2002), 对于改善社交互动, 调节认知加工, 预测未来行为都极为重要(Bristow et al., 2005)。前人研究表明, 目光注视方向能够引导注意分配(Chita-Tegmark, 2016; Fischer, 1999; Song et al., 2021)。例如, 直视可以捕获注意, 直视面孔比回避面孔被识别得更快, 更具吸引力(胡中华 等, 2013; Böckler et al., 2014); 直视也可以维持注意, 即对直视面孔存在脱离困难(Hietanen et al., 2016; Dalmaso et al., 2017), 直视的眼睛具有更大的黑白对比度区域, 可能会导致注意力停留时间的延长(Senju & Hasegawa, 2005)。并且, 对目光的优先注意从婴儿期起就已经出现, 他们更偏好睁眼尤其是直视的面孔(Farroni et al., 2002)。

客体也可以引导注意分配(Chen, 2012; Lee & Shomstein, 2013; Shomstein & Behrmann, 2008)。客体对注意分配的引导我们称之为客体注意, 它是指个体对相同客体内两个(或多个)特征的识别比对不同客体内两个(或多个)特征的识别更快更准确(Shomstein, 2012)。然而, 传统的空间线索范式并不能完全的将空间注意和客体注意相分离。Egly等人采用双框线索范式首次将客体注意(object-based attention, OBA)和空间注意(space-based attention, SBA)相分离(Egly et al., 1994)。在这个范式中, 首先呈现给被试两个水平或垂直排列的矩形框和一个注视点, 之后线索出现在两个矩形框的任意一端, 接着目标会随机出现在线索位置(有效, valid condition), 线索化矩形框的另一端(无效相同客体, invalid same-object condition, ISO)或者非线索化矩形框上(无效不同客体, invalid different-object condition, IDO), 且ISO和IDO与线索位置之间的距离相等。结果表明, 被试对有效位置上目标的反应显著快于ISO和IDO位置, 即出现了空间注意效应; 被试对ISO位置上目标的反应显著快于IDO位置, 即出现了一种客体引导的注意优势效应。

实际上, 在社会交往中, 除了面孔的目光注视信息, 面孔的客体属性也会引导我们的注意分配。研究发现, 对面孔的注意可以激活梭状回面孔区(fusiform face area, FFA)和额下联合皮层(inferior frontal junction, IFJ), 而IFJ被认为是OBA的神经基础(Baldauf & Desimone 2014)。此外, 如前所述, 不包含目光注视的客体本身就能够引导注意分配(Hu et al., 2020; Egly et al., 1994; Shomstein & Behrmann, 2008; Shomstein & Johnson, 2013; Song et al., 2020; Yeshurun & Rashal, 2017; Zhao et al., 2020)。那么, 值得我们关注的是, 携带社交信息的目光注视信号与客体是否以及如何交互引导注意?因此, Song等(2021)采用面孔和倒置面孔刺激并操纵SOA为300 ms, 发现直视条件下的OBA效应显著大于回避条件, 表明携带社交信息的目光注视信号能够与面孔客体交互作用来引导注意分配(Song et al., 2021)。另外, 他们采用眼睛叠加矩形框作为刺激, 得到了相似的效应, 据此认为目光注视影响OBA具有普遍机制。

然而, 前人关于目光注视影响OBA的研究仍存在一些不足。首先, Song等(2021)采用的矩形框和真实客体在知觉属性、复杂程度、三维情境方面存在差异, 不能表明目光注视对OBA的影响具有普遍适用性。(1)矩形框属性单一, 而真实客体包含自上而下的高级语义属性和自下而上的低级特征属性(Malcolm & Shomstein, 2015)。前人研究表明客体的自上而下和自下而上属性对客体注意选择产生不同影响(Hu et al., 2020)。(2)矩形框只是简单的二维图形, 跟真实客体在复杂程度上有很大的差别, 研究发现注意资源是从线索位置分梯度扩散至其他位置, 而区域复杂性会阻碍梯度的扩散, 从而影响对目标的反应(Chen et al., 2020)。(3)现实生活中, 我们更多地与环境中的真实三维客体而不是二维图形进行交互(Korisky & Mudrik, 2021)。真实三维客体也能够引导注意的分配(Stephenson et al., 2017; Bayliss et al., 2006, 2007; Hudson et al., 2016), 它更容易捕获注意(Korisky & Mudrik, 2021)。然而, 面孔相比于其他真实三维客体更具有生物性(Crouzet et al., 2010), 存在着独特的加工优势(Zhou et al., 2021)和注意偏向(Simpson et al., 2014; Langton et al., 2008)。在面孔客体中观察到的目光注视对OBA的影响是否适用于其他真实客体仍不可知。基于杯子作为一种常见的真实客体, 多次被研究者用来考察联合注意(Stephenson et al., 2017; Bayliss et al., 2013), 喜好评价(Bayliss et al., 2006, 2007)等问题, 因此, 本研究除了面孔刺激之外, 还采用杯子作为刺激, 考察面孔加工消失后, 目光注视影响OBA的效果在其他真实的非生物客体中是否仍然存在, 以及其背后的认知机制是否相同。

其次, 不同线索靶子呈现间隔(stimulus onset asynchronies, SOAs)是影响OBA的一个重要因素(Jeurissen et al., 2016), 但是, 目前尚无研究直接探讨目光注视影响OBA的时间进程。一方面, 视觉注意是一个有节律的加工过程(Chakravarthi & Vanrullen, 2012; Landau & Fries, 2012; VanRullen, 2013), 随着SOA的延长, OBA效应呈现先增加后减小的变化过程。前人关于注视线索效应的研究采用空间线索范式发现在探测任务中, 短SOA (105 ms)条件下就可以产生显著的线索效应, 较长SOA (300 ms)的线索效应更稳定, 且在长SOA (1005 ms)时线索效应消失(Friesen & Kingstone, 1998); 国内研究者操纵200 ms、300 ms和500 ms的SOA, 发现300 ms SOA时的注视线索效应更大(张智君 等, 2015)。Jeurissen等人随机呈现200~600 ms SOA, 结果表明300 ms的OBA效应大于200 ms和600 ms (Jeurissen et al., 2016)。此外, 以往关于OBA的研究发现无论客体呈现时间长短, 客体的颜色等物理特征都会影响OBA效应, 这表明自下而上的加工会持续影响OBA (Shomstein & Behrmann, 2008)。Shomstein和Yantis (2004)发现, 400 ms SOA条件下OBA会受个体搜索策略等自上而下目标概率的调节, 600 ms SOA 条件下客体效应消失, 注意完全由目标概率引导, 但是200 ms SOA条件下OBA不受其影响。

另一方面, 目光注视在传达关于注意方向、心理状态的社会信息中发挥着重要作用(Frischen et al., 2007), 它包括了目光的解译、共情和社会注意(Kawai, 2011)等自上而下社会认知加工过程, 因此需要更长的时间才发挥作用。Ristic和Kingstone (2005)的研究中操纵SOA为100、300、600、1000 ms, 并给被试呈现一张既可被知觉为汽车, 也可被知觉为眼睛的图片, 结果发现当刺激被知觉为眼睛时在300 ms和600 ms SOA条件下产生了显著的线索效应, 被知觉为汽车时则没有, 这表明目光信息虽然以自下而上的方式捕获注意, 但其会受到自上而下加工的影响, 并且需要一定的时间发挥作用。因此, 为了进一步探讨Song等(2021)人研究中的目光注视这一自上而下信息对OBA效应的影响在短SOA时是否已经产生, 在长SOA时是否持续发挥作用, 本研究操纵SOA为100 ms、300 ms和600 ms, 我们推测100 ms SOA条件下OBA效应不受目光注视影响, SOA为300 ms时目光注视会影响OBA效应, 且直视条件下的OBA效应大于回避条件, 但这种影响会在600 ms SOA条件下随着客体效应的减弱而消失。

综上, 本研究采用双框线索范式考察不同SOA条件下目光注视对OBA的影响。研究包含3个实验, 实验1选取直视面孔和回避面孔作为实验刺激, 考察目光注视如何与面孔客体交互作用来影响选择性注意。为了排除低水平物理特征的影响, 实验2将面孔对比度反转(Ramamoorthy et al., 2019)。实验3使用眼睛刺激叠加杯子的方式考察当面孔知觉消除后, 目光注视如何影响真实非生物客体的OBA。实验假设, 直视条件下的客体效应大于回避条件下的客体效应, 差异如果来自于直视和回避条件下被试对ISO位置目标的不同反应, 则表明直视面孔捕获注意, 导致被试对直视面孔非线索化位置上的目标反应更快; 如果差异来自于被试对IDO位置目标的不同反应, 则表明直视面孔维持注意, 导致被试对回避面孔上的目标反应更慢; 如果差异同时来自于ISO和IDO位置, 则表明直视面孔既捕获又维持注意。

2 实验1:不同SOA条件下目光注视对面孔客体注意的影响

2.1 方法

2.1.1 被试

一方面基于G* Power先验分析, 先评估一个中等大小的2×3×3交互作用的效应量(f = 0.25; Cohen, 1992), 并设置α值为0.05, 统计检验力为0.95 (Faul et al., 2009), 计算得到的样本量为14人。另一方面, 基于以往关于OBA研究中的样本量(Zhao et al., 2020; Yeshurun & Rashal, 2017), 得到最终的计划样本量为20~30人, 以确保足够的统计效力。实验1招募陕西师范大学25名在校大学生参加了本实验(女生23名, 男生2名), 被试年龄在17~23岁之间(M = 18, SD = 1.39)。所有被试均为右利手, 视力或矫正视力正常, 未参加过相似实验。实验开始前, 已获得所有被试的知情同意, 实验结束后, 给予被试一定报酬。

2.1.2 实验仪器和材料

实验所用仪器为19英寸的联想L1900PA显示器, 屏幕分辨率为1280×1024, 刷新率为60 Hz。被试眼睛与显示器的距离约为63 cm。我们采用E-prime 2.0进行实验编程, 实验所用材料为两张大小为2°×4.9°的面孔, 它们中间存在一个0.48°×0.48°的中央注视点, 两张面孔之间距离是0.9°视角。线索是一个黄色轮廓, 它随机出现在面孔的上下任意一端上。目标是一个直径为0.48°的白色圆点。我们采用9点量表让被试评价了面孔的愉悦度(1为极度不愉快, 9为极度愉快), 结果直视(M = 4.97, SE = 0.36)和回避(M = 5.27, SE = 0.40)的面孔差异不显著, p > 0.05; 面孔唤醒度(1为极度平静, 9为极度激动)的评价结果发现, 直视(M = 5.63, SE = 0.29)和回避(M = 5.17, SE = 0.35)面孔差异不显著, p > 0.05。

2.1.3 实验设计

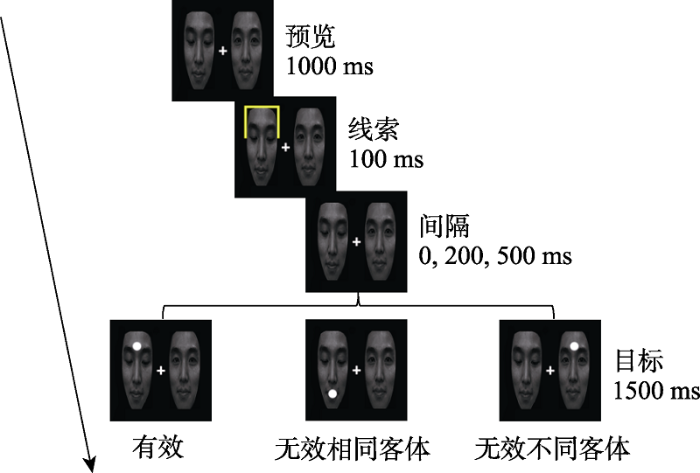

实验采用2 (提示线索所在位置:直视、回避) × 3 (线索有效性:有效、无效相同客体、无效不同客体) × 3 (SOA:100 ms、300 ms、600 ms)被试内设计。提示线索所在位置指提示线索出现在直视或回避的面孔上, 如图1中的线索屏所示。其中, 提示线索所在位置, 有效性和SOA为被试内变量, 因变量为反应时和正确率。正式实验约60分钟, 包含6个block, 共1038个试次, 为了引起被试的警觉, 实验中包括了没有目标出现的空白试次, 其中目标试次864个, 空白试次为174个。在目标试次中, 目标出现在线索化位置(有效)的概率为50%, 目标出现在线索化客体的另一端(ISO)或者非线索化客体上(IDO)的概率均为25%。

图1

2.1.4 实验流程

实验流程如图1所示。实验开始时, 首先, 在屏幕中央呈现1000 ms中央注视点“+”和两张面孔, 紧接着两张面孔的任意一端出现黄色的线索(RGB: 255, 255, 0), 呈现时间为100 ms, 然后注视点和面孔继续呈现0 ms、200 ms或者500 ms之后, 除空白试次之外, 目标圆点出现在两面孔的任一末端。目标在被试做出反应时消失, 若被试未做出反应则持续1500 ms后消失。在500 ms的空屏后进入下一试次。被试的任务是当察觉到目标时尽可能快的按下“M”键, 没有目标出现时则不按键。在正式实验前, 被试需要完成20个试次的练习实验, 当正确率达到90%以上时才能进入正式实验。

2.2 数据分析与结果

采用SPSS 16.0对实验数据进行分析, 每个被试的正确率均在90%以上, 空白试次的平均错报率为2.0%。在进行正式分析之前, 剔除了错误反应以及3个标准差以外的反应时, 剔除率为1.8%。我们对数据结果进行2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视、回避) × 3 (线索有效性: 有效、无效相同客体、无效不同客体) × 3 (SOA:100 ms、300 ms、600 ms)三因素重复测量方差分析。反应时的描述性统计结果见表1, 结果显示, SOA的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 78.38, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.77。事后检验发现, SOA为300 ms条件(M = 326 ms, SE = 8.67)被试的反应快于SOA为100 ms条件(M = 357 ms, SE = 8.74), p < 0.001, 95% CI = [-36.35, -24.77], 和600 ms (M = 350 ms, SE = 8.85)条件, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [-28.22, -18.07], SOA为100 ms和600 ms时被试的反应不存在显著差异, p = 0.094, 95% CI = [-15.76, 0.93]。提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 0.87, p = 0.361。线索有效性的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 6.06, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.20, 被试在ISO条件下的反应(M = 341 ms, SE = 8.77)显著快于IDO条件(M = 348 ms, SE = 8.85), 这表明产生了显著的OBA效应, 有效条件下的反应与ISO条件和IDO条件下的反应没有显著差异。SOA和提示线索所在位置的交互作用不显著, F (2, 48) = 1.83, p = 0.175。SOA和线索有效性的交互作用显著, F (4, 96) = 3.56, p = 0.013, ηp2 = 0.13。线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的交互作用不显著, F (2, 48) = 0.52, p = 0.592。SOA, 线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的三重交互作用不显著, F (4, 96) = 2.30, p = 0.081。

表1 实验1中SOA、提示线索所在位置和线索有效性各条件下的平均反应时(M ± SD)

| SOA | 直视 | 回避 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 有效 | 无效相同 | 无效不同 | 有效 | 无效相同 | 无效不同 | |

| 100 ms | 358 ± 43 | 353 ± 47 | 360 ± 43 | 359 ± 41 | 351 ± 46 | 361 ± 48 |

| 300 ms | 321 ± 44 | 320 ± 45 | 333 ± 45 | 326 ± 41 | 327 ± 47 | 331 ± 46 |

| 600 ms | 350 ± 47 | 349 ± 47 | 350 ± 44 | 350 ± 47 | 346 ± 43 | 352 ± 47 |

为了进一步探究SOA对OBA的影响, 我们对反应时数据进行了2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视、回避) × 2 (线索有效性: 无效相同客体、无效不同客体) × 3 (SOA: 100 ms、300 ms、600 ms)重复测量方差分析。结果发现, SOA的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 65.78, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.73; 提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 0.11, p = 0.740; 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 18.02, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.43。所有的二重交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。重要的是, SOA, 线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的三重交互作用显著, F (2, 48) = 3.79, p = 0.037, ηp2 = 0.14。

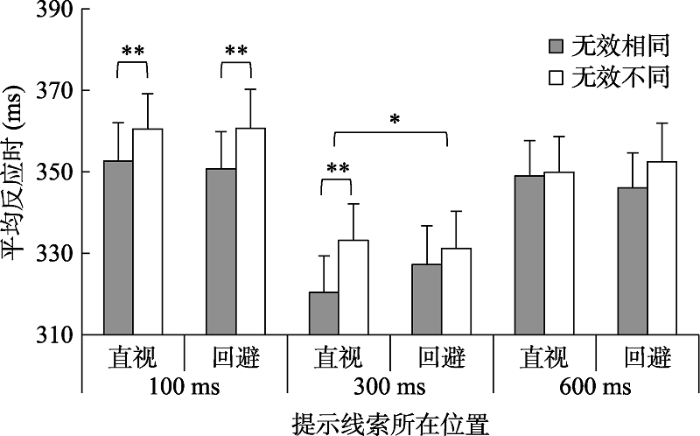

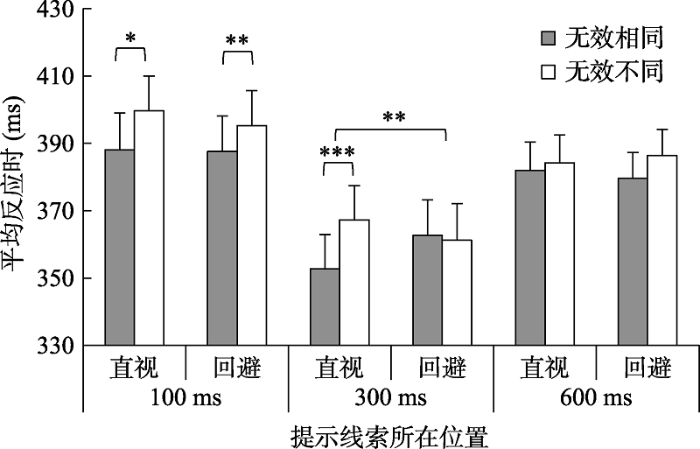

因此, 我们在单个SOA条件下均进行了2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视, 回避) × 2 (线索有效性: 无效相同客体, 无效不同客体)重复测量方差分析。当SOA为100 ms时, 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 36.28, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.60, 表明对线索的自下而上注意导致了OBA效应; 提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 0.12, p = 0.733; 提示线索所在位置和线索有效性的交互作用不显著, F (1, 24) = 0.28, p = 0.603, 这表明100 ms SOA时提示线索所在位置为直视和回避条件下的OBA效应没有差异(见图2); 当SOA为300 ms时, 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 8.98, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.27, 表明出现了OBA效应; 提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 1.78, p = 0.195; 提示线索所在位置和线索有效性的交互作用显著, F (1, 24) = 7.17, p = 0.013, ηp2 = 0.23, 这表明对线索的自下而上注意以及对目光注视的自上而下注意交互影响了注意分配, 导致300 ms SOA时提示线索所在位置为直视和回避条件下的OBA效应存在差异, 进一步分析发现, 直视条件下的OBA效应(M = 12.79 ms, SE = 3.29)显著大于回避条件(M = 3.94 ms, SE = 3.20), t (24) = -2.68, p = 0.013, Cohen’s d = 0.55, 95% CI = [-15.67, -2.03], 且这种差异来自于直视条件下被试对ISO位置的目标反应快于回避条件,t(24) = 2.59, p = 0.016, Cohen’s d = 0.15, 95% CI = [1.40, 12.37], 直视条件与回避条件下被试对IDO位置的目标反应没有差异, t (24) = -0.86, p = 0.396, Cohen’s d = 0.04, 95% CI = [-6.67, 2.73], 这表明直视相比于回避面孔更能捕获注意, 该结果支持注意捕获而不是注意维持假设; 当SOA为600 ms时, 主效应和交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05), 这表明600 ms SOA时提示线索所在位置为直视和回避条件下均未出现OBA效应。

图2

正确率的结果分析发现, 所有主效应以及交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。因此, 本实验不存在正确率和反应时的权衡现象。

2.3 讨论

实验1结果发现, 当SOA为300 ms时, 直视条件下的客体效应大于回避条件, 且这种差异来自于被试对直视条件下ISO位置目标的探测反应显著快于回避条件下ISO位置目标, 表明直视捕获注意。另外, 600 ms SOA条件下, 并没有产生OBA效应, 表明了OBA效应会随着线索目标间隔时间的增加而减少, 这与前人研究结果一致(Chou & Yeh, 2018; Drummond & Shomstein, 2010; Shomstein & Yantis, 2004)。另外, 为了排除眼白、明暗对比等低水平物理特征的影响, 实验2将面孔的对比度反转。研究发现当巩膜和瞳孔的相对对比度从正(即虹膜比巩膜暗)变为负极性(即巩膜比虹膜暗)时, 由眼白、对比度等造成的影响不会发生变化, 但成年人判断注视方向时会非常不准确(Ricciardelli, 2009), 并且目光注视的效果会消失(Ramamoorthy et al., 2019)。实验假设, 如果300 ms SOA条件下产生直视和回避条件下客体效应无差异, 表明实验1的结果是由于对注视信息的编码加工; 如果实验2结果和实验1一致, 表明对比度的差异这一低水平物理特征是导致实验1结果的重要因素。

3 实验2:不同SOA条件下目光注视对反相面孔客体注意的影响

3.1 方法

3.1.1 被试

陕西师范大学25名在校大学生被招募参与此实验(女生23名, 男生2名), 被试年龄在17~21岁之间(M = 19, SD = 1.03)。所有被试的视力或矫正视力正常, 从未参加过类似实验。实验开始前, 已获得所有被试的知情同意, 实验结束后, 给予被试一定报酬。

3.1.2 实验仪器, 材料

实验材料和仪器与实验1相似, 不同之处在于实验2所采用的客体是将实验1中面孔的对比度反转, 其他部分和实验1相同。

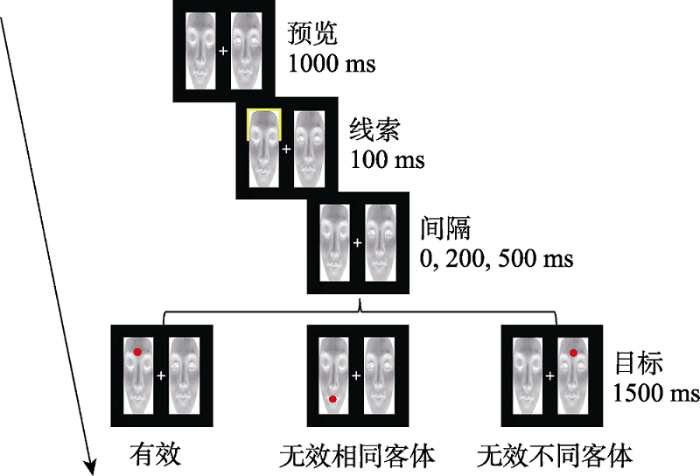

3.1.3 实验设计和流程

实验设计与流程同实验1, 如图3所示。

图3

3.2 数据分析与结果

每个被试的正确率均在90%以上, 空白试次的平均错报率为1.6%。数据分析方法与实验1相同, 在进行正式分析之前, 剔除了错误反应以及3个标准差以外的反应时, 剔除率为2.2%。我们对数据结果进行2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视、回避) × 3 (线索有效性: 有效、无效相同客体、无效不同客体) × 3 (SOA: 100 ms、300 ms、600 ms)三因素重复测量方差分析。反应时的描述性统计结果见表2, 结果显示, SOA的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 90.95, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.79。事后检验发现, SOA为300 ms条件(M = 343 ms, SE = 9.09)被试的反应快于SOA为100 ms条件(M = 378 ms, SE = 8.95), p < 0.001, 95% CI = [-40.41, -29.36]和600 ms (M = 369 ms, SE = 9.24)条件, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [-33.58, -19.30], SOA为600 ms时被试的反应快于100 ms条件, p = 0.035, 95% CI = [-16.39, -0.50]。提示线索所在位置的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 11.93, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.33, 被试对线索在回避条件下的反应(M = 362 ms, SE = 8.93)显著快于线索在直视条件(M = 365 ms, SE = 9.00)。线索有效性的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 16.17, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.40, 被试在有效条件下的反应(M = 361ms, SE = 8.71)显著快于IDO条件, ISO条件下被试的反应(M = 360 ms, SE = 8.79)显著快于IDO条件(M = 369 ms, SE = 9.49), 这表明产生了显著的OBA效应。SOA和线索有效性的交互作用显著, F (4, 96) = 4.92, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.17。SOA和提示线索所在位置的交互作用显著, F (2, 48) = 5.76, p = 0.006, ηp2 = 0.19。线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的交互作用不显著, F (2, 48) = 1.44, p = 0.247。SOA, 线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的三重交互作用不显著, F (4, 96) = 2.20, p = 0.095。

表2 实验2中SOA、提示线索所在位置和线索有效性各条件下的平均反应时(M ± SD)

| SOA | 直视 | 回避 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 有效 | 无效相同 | 无效不同 | 有效 | 无效相同 | 无效不同 | |

| 100 ms | 382 ± 47 | 372 ± 42 | 388 ± 49 | 375 ± 44 | 371 ± 47 | 378 ± 46 |

| 300 ms | 339 ± 46 | 340 ± 42 | 354 ± 54 | 335 ± 41 | 341 ± 48 | 347 ± 49 |

| 600 ms | 368 ± 46 | 368 ± 47 | 369 ± 47 | 368 ± 46 | 368 ± 47 | 375 ± 50 |

为了进一步探究SOA对OBA的影响, 我们对反应时数据进行了2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视、回避) × 2 (线索有效性: 无效相同客体、无效不同客体) × 3 (SOA: 100 ms、300 ms、600 ms)重复测量方差分析。结果发现, SOA的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 64.02, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.73; 提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 3.96, p = 0.058; 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 31.64, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.57。SOA和提示线索所在位置的交互作用显著, F (2, 48) = 5.66, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.19; 其他的二重交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。重要的是, SOA, 线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的三重交互作用显著, F (2, 48) = 3.34, p = 0.046, ηp2 = 0.12。

因此, 我们在单个SOA条件下均进行了2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视, 回避) × 2 (线索有效性: 无效相同客体, 无效不同客体)重复测量方差分析。当SOA为100 ms时, 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 22.08, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.48, 表明对线索的自下而上注意导致了OBA效应; 提示线索所在位置的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 10.12, p = 0.004, ηp2 = 0.30, 表明线索在直视和回避条件下的加工存在差异; 提示线索所在位置和线索有效性的交互作用不显著, F (1, 24) = 3.28, p = 0.083, 这表明100 ms SOA时提示线索所在位置为直视和回避条件下的OBA效应没有差异(见图4); 当SOA为300 ms时, 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 12.68, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.35, 表明对线索的自下而上注意导致了OBA效应; 提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 3.70, p = 0.066; 提示线索所在位置和线索有效性的交互作用不显著, F (1, 24) = 2.36, p = 0.138, 这表明300 ms SOA时提示线索所在位置为直视和回避条件下的OBA效应没有差异; 当SOA为600 ms时, 主效应和交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05), 这表明600 ms SOA时直视和回避条件下均未出现OBA效应。

图4

正确率的结果分析发现, 所有主效应以及交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。因此, 本实验不存在正确率和反应时的权衡现象。

3.3 讨论

实验2只是将实验1的对比度反转, 并没有改变对比度的差异, 结果在300 ms SOA条件下直视和回避条件下的客体效应没有差异, 证明了正是由于对目光注视信息的编码而不是对比度等低水平物理特征导致实验1的结果。600 ms SOA条件下, 没有产生OBA效应, 与实验1结果一致。另外, 为了考察当面孔知觉消除后, 目光注视对OBA的影响是否能够扩展到其他真实客体中, 实验3使用非生物的杯子叠加眼睛作为刺激。如果实验3中没有出现目光注视效应, 表明目光注视的OBA依赖于对整个面孔信息的加工, 如果与实验1结果相似, 表明当面孔信息被消除后, 目光注视对OBA分配的影响可以扩展到其他真实客体中。

4 实验3:不同SOA条件下目光注视对真实客体注意的影响

4.1 方法

4.1.1 被试

陕西师范大学25名在校大学生被招募参与此实验(女生23名, 男生2名), 被试年龄在17~20岁之间(M = 18, SD = 0.64)。所有被试的视力或矫正视力正常, 从未参加过类似实验。实验开始前, 已获得所有被试的知情同意, 实验结束后, 给予被试一定报酬。

4.1.2 实验仪器和材料

实验材料和仪器与实验1相似, 不同之处在于实验3所采用的客体是两个灰度处理后的杯子叠加眼睛, 其他部分和实验1相同。

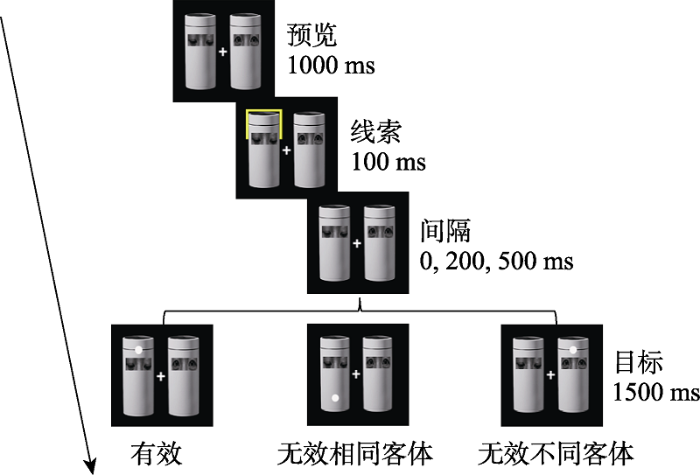

4.1.3 实验设计和流程

实验设计与流程与实验1相同, 如图5所示。

图5

4.2 数据分析与结果

每个被试的正确率均在90%以上, 空白试次的错报率为1.7%。数据分析方法与实验1相同, 在进行正式分析之前, 剔除了错误反应以及3个标准差以外的反应时, 剔除率为2.3%。我们对数据结果进行2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视、回避) × 3 (线索有效性: 有效、无效相同客体、无效不同客体) × 3 (SOA: 100 ms、300 ms、600 ms)三因素重复测量方差分析。反应时的描述性统计结果见表3, 结果显示, SOA的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 48.29, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.67。事后检验发现, SOA为300 ms条件(M = 357 ms, SE = 9.48)被试的反应快于SOA为100 ms条件(M = 391 ms, SE = 9.84), p < 0.001, 95% CI = [-41.58, -27.17]和600 ms (M = 382 ms, SE = 7.71)条件, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [-33.60, -16.72], SOA为100 ms和600 ms时被试的反应不存在显著差异, p = 0.163, 95% CI = [-20.93, 2.51]。提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 0.39, p = 0.536。线索有效性的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 11.73, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.33, 被试在有效条件下的反应(M = 372 ms, SE = 8.13)显著快于IDO条件, ISO条件下被试的反应(M = 375 ms, SE = 9.36)显著快于IDO条件(M = 382 ms, SE = 9.16), 这表明产生了显著的OBA效应。SOA和线索有效性的交互作用显著, F (4, 96) = 3.58, p = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.13。SOA和提示线索所在位置的交互作用不显著, F (2, 48) = 0.93, p = 0.395。线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的交互作用不显著, F (2, 48) = 2.06, p = 0.138。SOA, 线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的三重交互作用不显著, F (4, 96) = 2.45, p = 0.063。

表3 实验3中SOA、提示线索所在位置和线索有效性各条件下的平均反应时(M ± SD)

| SOA | 直视 | 回避 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 有效 | 无效相同 | 无效不同 | 有效 | 无效相同 | 无效不同 | |

| 100 ms | 389 ± 46 | 388 ± 54 | 400 ± 51 | 387 ± 44 | 388 ± 53 | 395 ± 52 |

| 300 ms | 348 ± 38 | 353 ± 51 | 367 ± 51 | 349 ± 46 | 363 ± 52 | 361 ± 55 |

| 600 ms | 381 ± 41 | 382 ± 42 | 384 ± 42 | 378 ± 39 | 380 ± 39 | 386 ± 39 |

为了进一步探究SOA对OBA的影响, 我们对反应时数据进行了2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视、回避) × 2 (线索有效性: 无效相同客体、无效不同客体) × 3 (SOA: 100 ms、300 ms、600 ms)重复测量方差分析。结果发现, SOA的主效应显著, F (2, 48) = 33.62, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.58; 提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 0.02, p = 0.893; 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 17.82, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.43。所有的二重交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。重要的是, SOA, 线索有效性和提示线索所在位置的三重交互作用显著, F (2, 48) = 4.05, p = 0.025, ηp2 = 0.14。

因此, 我们在单个SOA条件下均进行了2 (提示线索所在位置: 直视, 回避) × 2 (线索有效性: 无效相同客体, 无效不同客体)重复测量方差分析。当SOA为100 ms时, 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 17.03, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.42, 表明对线索的自下而上注意导致了OBA效应; 提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 1.81, p = 0.192; 提示线索所在位置和线索有效性的交互作用不显著, F (1, 24) = 0.59, p = 0.450, 这表明100 ms SOA时提示线索所在位置为直视和回避条件下的OBA效应没有差异(见图6); 当SOA为300 ms时, 线索有效性的主效应显著, F (1, 24) = 9.62, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.29, 表明出现了OBA效应; 提示线索所在位置的主效应不显著, F (1, 24) = 0.41, p = 0.531; 提示线索所在位置和线索有效性的交互作用显著, F (1, 24) = 8.13, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.25, 这表明对线索的自下而上注意以及对目光注视的自上而下注意交互影响了注意分配, 导致300 ms SOA时提示线索所在位置为直视和回避条件下的OBA效应存在差异, 进一步分析发现, 直视条件下的OBA效应(M = 14.61 ms, SE = 3.41)显著大于回避条件(M = -1.50 ms, SE = 3.64), t (24) = -2.85, p = 0.009, Cohen’s d = 0.91, 95% CI = [-27.76, -4.45], 且这种差异来自于直视条件下被试对ISO位置的目标反应快于回避条件, t (24) = 2.35, p = 0.027, Cohen’s d = 0.19, 95% CI = [1.23, 18.76], 直视条件与回避条件下被试对IDO位置的目标反应没有差异, t (24) = -1.50, p = 0.147, Cohen’s d = 0.12, 95% CI = [-14.51, 2.30], 这表明直视相比于回避面孔更能捕获注意, 该结果支持注意捕获而不是注意维持假设; 当SOA为600 ms时, 主效应和交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05), 这表明600 ms SOA时直视和回避条件下均未出现OBA效应。

图6

正确率的结果分析发现, 所有主效应以及交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。因此, 本实验不存在正确率和反应时的权衡现象。

4.3 讨论

实验3的结果与实验1也相似, 即300 ms SOA条件下直视条件下的客体效应显著大于回避条件, 且这种差异来自于被试对两种条件下ISO位置目标的不同反应, 表明直视捕获注意, 进一步证明了目光注视对OBA的影响也可以扩展到其他真实客体中。600 ms SOA条件下, 并没有产生OBA效应。

5 讨论

本研究通过3个实验, 分别以有目光注视的面孔、杯子作为刺激, 揭示了在双框线索范式中目光注视对OBA的影响受到SOA的调节, 目光注视对OBA效应的影响在较长SOA (300 ms)条件下出现, 在较短(100 ms)和更长SOA (600 ms)时消失。实验1使用面孔刺激并操纵不同的SOA, 考察了目光注视与面孔是否交互引导注意分配, 300 ms SOA时, 被试对直视面孔ISO位置上目标的探测要快于回避面孔, 导致更大的OBA效应, 这表明与回避条件相比, 直视更能捕获我们的注意。实验2将面孔的对比度反转, 结果没有产生直视和回避条件下客体效应的差异, 表明实验1的结果是由于被试对目光注视信息的编码而不是由于对比度等低水平特征导致的。实验3采用眼睛叠加杯子的刺激发现面孔知觉消失后, 出现了与实验1相似的结果。3个实验结果一致表明, 直视捕获注意, 使注意资源更容易从线索位置分配到了ISO位置, 此外, 目光注视能够影响基于客体的注意分配, 这种影响也可以扩展到真实客体中。

本研究结果发现, 直视与回避条件下的客体注意效应存在差异, 且这种差异来自于被试对直视客体ISO位置上目标的探测要快于回避客体, 这个结果符合客体注意的感觉增强假说。目前解释OBA效应的主流理论有3种, 即感觉增强理论(sensory enhancement theory)、注意转移理论(attentional shifting theory)和注意优先理论(attentional priorization theory)。早期的感觉增强理论是Desimone和Duncan(1995)提出的偏向竞争模型, 他们认为感觉增强可能是多客体间神经表征偏向竞争的结果, 该竞争导致与未线索化客体相比, 线索化客体的表征变得更为有效, 使得个体能够优先选择该客体。而对线索化客体的选择又反过来使该客体内特征的加工变得更快、更准。现有的感觉增强理论认为, 注意在客体内扩散并受制于客体边界, 从而导致线索化客体的感觉表征增强, 所以对该客体的特征或客体内的项目反应更快更准(Conci & Muller, 2009; Richard et al., 2008; Shomstein, 2012)。然而, 注意转移理论认为, 在从一个客体转移到另一个客体时有更高的损耗(Brown & Denney, 2007; Ushitani et al., 2010; Yeshurun & Rashal, 2017)。注意优先理论则认为, OBA效应是由于视觉搜索过程中对不同位置的注意优先性不同导致的, 视觉搜索默认地始于线索化客体中的位置, 从而导致对非线索化客体的搜索晚于线索化客体(Drummond & Shomstein, 2010; Shomstein, 2012; Yeshurun & Rashal, 2017)。如果直视面孔捕获注意, 那么它将会被分配更多的注意资源, 从而进一步增强其表征强度。因此, 被试对直视面孔ISO位置上目标的探测要快于回避面孔, 导致更大的OBA效应。这个假设与感觉增强理论一致。如果直视面孔维持了注意, 导致从直视面孔上脱离难于回避面孔, 那么被试对直视面孔IDO位置上目标的探测要慢于回避面孔, 导致更大的OBA效应。这个假设与注意转移理论一致。如果直视面孔既捕获注意又维持注意, 那么被试对ISO和IDO上目标的反应在直视面孔和回避面孔之间都有差异。这个假设与注意优先理论一致。本研究结果显示, 相比于回避面孔, 直视面孔优先捕获了被试的注意, 其感觉表征被进一步增强, 导致在300 ms SOA时ISO有更好的表现, 即OBA效应的产生来源于目光注视对ISO位置自上而下的易化加工。这与感觉增强理论一致。

本研究结果发现, OBA效应会随着线索目标间隔时间的增加而减少, 这与前人研究结果一致(Chou & Yeh, 2018; Drummond & shomstein, 2010; Shomstein & Yantis, 2004)。更重要的是, 本研究只在300 ms SOA条件下出现了直视和回避客体效应的差异, 这与前人研究结果一致(Song et al., 2021)。分析其原因:当线索突然出现时, 注意会被自下而上地捕获并转移到线索位置(Posner, 1980), 短时间内只有线索在发挥作用, 因此本研究中100 ms SOA条件下出现了客体效应, 且不受目光注视影响; 随着时间的推移, 注视线索开始发挥作用, 这与前人关于目光注视受自上而下的加工影响, 对注视方向进行编码需要时间(Bayliss & Tipper, 2006; Kawai, 2011)的结果一致, 因此, 在300 ms时出现了目光注视与客体注意的交互作用; 由于SOA时间的增长, 可能使得被试对线索产生了心理准备, 从而降低了线索空间定向的重要性(彭姓 等, 2019), 另外, Lou等人(2021)发现只有在线索目标130~190 ms, 230~260 ms, 500~530 ms等时间间隔时才会产生客体效应, 因此600 ms SOA条件下随着线索效应的消失, 目光注视也不再对OBA产生作用。综上所述, 本研究结果表明目光注视对OBA的影响比较短暂, 出现得晚, 消失得快。

值得注意的是, 本研究中, 当面孔信息被消除之后, 目光注视对OBA效应的影响也可以发生在其他真实客体上, 表明这种影响具有普遍适用性。这与前人的研究结果一致, 在面孔消失后, 单独的眼睛或眼睛叠加其他刺激也可以产生线索效应(Green et al., 2013; Ristic & Kingstone, 2005)。Itier等人提出的面孔加工神经模型认为在大脑颞上沟(superior temporal sulcus, STS)区域可能存在着两种神经元, 当存在正立面孔时, 主要是面孔选择神经元起作用, 然而改变面孔对比度或将面孔倒置时, 这时眼睛处于非正常的人脸环境中, 眼睛选择神经元和面孔神经元会共同起作用, 从而产生相似且比正立面孔更大的N170波幅。该模型认为这一结果是由于对眼睛区域的加工引起的。在该研究中, 单独眼睛刺激产生的波幅总是大于面孔产生的波幅, 去掉眼睛产生的波幅和面孔相似, 所以正是因为眼睛的存在才导致面孔如此特别(Itier et al., 2007), 这与我们的研究结果一致。

本研究首次考察了当我们进行社交互动时, OBA随着SOA变化的趋势, 然而也存在一定的局限性。本研究主要关注的是目光注视方向, 然而与面孔有关的眼睛运动(Bockler et al., 2014; 陈艾睿等, 2014), 面部倒置(Murphy & Cook, 2017), 头部朝向(Otsuka & Clifford, 2018)等因素是否会影响OBA还需要进一步考察; 本研究的性别比例相对不平衡, 这是因为本研究被试招募是随机的。研究发现女性相比男性在面孔识别以及加工社会线索时具有优势(Bayliss et al., 2005), 因此未来研究可以考虑更好的控制性别比例。此外, 现有研究关于社会性的目光注视线索和非社会性的箭头线索加工是否存在差异仍存在争议(纪皓月 等, 2017), 社会性注意线索相比于箭头等非社会线索更具有反射性, 更不易受到自上而下的影响(Friesen et al., 2004), 因此未来研究也可以探索箭头线索是否能产生本研究中类似的认知机制。最后, 不同文化下目光注视方向影响OBA的变化趋势也值得探讨(霍鹏辉等, 2021), 例如, 日本人认为与他人进行大量目光交流意味着不敬, 然而在中国意味着对谈话人的礼貌和兴趣(Uono & Hietanen, 2015); 亚洲人通常表现出对面部中央区域的集中注视, 而高加索人则主要集中注视眼睛和嘴巴区域(Blais et al., 2008)。

6 结论

(1)目光注视方向可以与客体交互引导注意分配, 直视的目光更容易捕获注意, 目光注视对ISO位置自上而下的易化加工导致了更大的OBA效应, 这支持了感觉增强理论;

(2)目光注视对OBA的影响受SOA调节, 这种影响出现得较晚, 并且消失得较快;

(3)目光注视对OBA的影响具有普遍适用性, 不仅可以发生在面孔作为客体时, 也可以扩展到其他真实客体中。

参考文献

Neural mechanisms of object-based attention

DOI:10.1126/science.1247003

PMID:24763592

[本文引用: 1]

How we attend to objects and their features that cannot be separated by location is not understood. We presented two temporally and spatially overlapping streams of objects, faces versus houses, and used magnetoencephalography and functional magnetic resonance imaging to separate neuronal responses to attended and unattended objects. Attention to faces versus houses enhanced the sensory responses in the fusiform face area (FFA) and parahippocampal place area (PPA), respectively. The increases in sensory responses were accompanied by induced gamma synchrony between the inferior frontal junction, IFJ, and either FFA or PPA, depending on which object was attended. The IFJ appeared to be the driver of the synchrony, as gamma phases were advanced by 20 ms in IFJ compared to FFA or PPA. Thus, the IFJ may direct the flow of visual processing during object-based attention, at least in part through coupled oscillations with specialized areas such as FFA and PPA.

Sex differences in eye gaze and symbolic cueing of attention

DOI:10.1080/02724980443000124 URL [本文引用: 1]

Affective evaluations of objects are influenced by observed gaze direction and emotional expression

Gaze direction signals another person's focus of interest. Facial expressions convey information about their mental state. Appropriate responses to these signals should reflect their combined influence, yet current evidence suggests that gaze-cueing effects for objects near an observed face are not modulated by its emotional expression. Here, we extend the investigation of perceived gaze direction and emotional expression by considering their combined influence on affective judgments. While traditional response-time measures revealed equal gaze-cueing effects for happy and disgust faces, affective evaluations critically depended on the combined product of gaze and emotion. Target objects looked at with a happy expression were liked more than objects looked at with a disgust expression. Objects not looked at were rated equally for both expressions. Our results demonstrate that facial expression does modulate the way that observers utilize gaze cues: Objects attended by others are evaluated according to the valence of their facial expression.

“Gaze Leading”: Initiating simulated joint attention influences eye movements and choice behavior

DOI:10.1037/a0029286 URL [本文引用: 1]

Gaze cuing and affective judgments of objects: I like what you look at

DOI:10.3758/BF03213926 URL [本文引用: 2]

Gaze cues evoke both spatial and object-centered shifts of attention

DOI:10.3758/BF03193678 URL [本文引用: 1]

Culture shapes how we look at faces

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0003022 URL [本文引用: 1]

Catching eyes: Effects of social and nonsocial cues on attention capture

DOI:10.1177/0956797613516147 URL [本文引用: 2]

Two distinct neural effects of blinking on human visual processing

Humans blink every few seconds, yet the changes in retinal illumination during a blink are rarely noticed, perhaps because visual sensitivity is suppressed. Furthermore, despite the loss of visual input, visual experience remains continuous across blinks. The neural mechanisms in humans underlying these two phenomena of blink suppression and visual continuity are unknown. We investigated the neural basis of these two complementary behavioural effects using functional magnetic resonance imaging to measure how voluntary blinking affected cortical responses to visual stimulation. Two factors were independently manipulated in a blocked design; the presence/absence of voluntary blinking, and the presence/absence of visual stimulation. To control for the simple loss of visual input caused by eyelid closure, we created a fifth condition where external darkenings were dynamically matched to each subjects' own blinks. Areas of lateral occipital cortex, including area V5/MT, showed suppression of responses to visual stimulation during blinking, consistent with the known loss in visual sensitivity. In contrast, a medial parieto-occipital region, homologous to macaque area V6A, showed responses to blinks that increased when visual stimulation was present. Our data are consistent with a role for this region in the active maintenance of visual continuity across blinks. Moreover, both suppression in lateral occipital and activation in medial parieto-occipital cortex were greater during blinks than during matched external darkenings of the visual scene, suggesting that they result from an extra-retinal signal associated with the blink motor command. Our findings therefore suggest two distinct neural correlates of blinking on human visual processing.

Shifting attention into and out of objects: Evaluating the processes underlying the object advantage

DOI:10.3758/BF03193918 URL [本文引用: 1]

Conscious updating is a rhythmic process

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1121622109 URL [本文引用: 1]

The role of cue type in the subliminal gaze-cueing effect

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.01281 URL [本文引用: 1]

线索类型对阈下注视线索效应的影响

Object-based attention: A tutorial review

DOI:10.3758/s13414-012-0322-z URL [本文引用: 1]

A region complexity effect masquerading as object- based attention

DOI:10.1167/jov.20.7.24

PMID:32692828

[本文引用: 1]

A large portion of the evidence for object-based attention comes from experiments using the two-rectangle paradigm introduced by Egly, Driver, and Rafal (1994), in which response times are longer when the two stimulus locations relevant to the task are on separate objects. In the new experiments presented here, response times are longer when the two locations are part of the same object but are separated by a concavity in the object, so that the region directly between the two locations is crossed by the object's boundaries. Response times when the two locations are separated by the concavity are not statistically different from when they are on two separate objects. The results are similar for a two-letter comparison task and for a spatial cuing task. Thus, in these experiments, the response time increase does not reflect the cost of shifting attention from object to object, because it appears when the two locations are on the same object, and it is not increased when they are on different objects. Instead, it seems to reflect the complexity of the region between the two stimulus locations. This finding raises questions about whether data from previous two-rectangle experiments should be attributed to object-based attention.

Attention allocation in ASD: A review and meta-analysis of eye-tracking studies

DOI:10.1007/s40489-016-0077-x URL [本文引用: 1]

Dissociating location-based and object-based cue validity effects in object-based attention

DOI:10.1016/j.visres.2017.11.008 URL [本文引用: 2]

A power primer

DOI:10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155

PMID:19565683

[本文引用: 1]

One possible reason for the continued neglect of statistical power analysis in research in the behavioral sciences is the inaccessibility of or difficulty with the standard material. A convenient, although not comprehensive, presentation of required sample sizes is provided here. Effect-size indexes and conventional values for these are given for operationally defined small, medium, and large effects. The sample sizes necessary for.80 power to detect effects at these levels are tabled for eight standard statistical tests: (a) the difference between independent means, (b) the significance of a product-moment correlation, (c) the difference between independent rs, (d) the sign test, (e) the difference between independent proportions, (f) chi-square tests for goodness of fit and contingency tables, (g) one-way analysis of variance, and (h) the significance of a multiple or multiple partial correlation.

The "beam of darkness": Spreading of the attentional blink within and between objects

DOI:10.3758/APP.71.8.1725 URL [本文引用: 1]

Fast saccades toward faces: Face detection in just 100 ms

Attention holding elicited by direct-gaze faces is reflected in saccadic peak velocity

DOI:10.1007/s00221-017-5059-4

PMID:28812119

[本文引用: 1]

Manual response times to peripherally presented targets have been reported to be greater in the presence of task-irrelevant pictorial faces at fixation which establish an eye contact with the observer. This effect is interpreted as evidence that direct-gaze faces hold attention. In three experiments, we investigated whether this attention-holding effect is also reflected in saccadic response times. Participants were asked to make a saccade towards a symbolic target that could appear rightwards or leftwards, in the presence of a task-irrelevant centrally placed face with either direct gaze or closed eyes. Unexpectedly, saccadic response times did not show any consistent response pattern as a function of whether the faces were presented with direct gaze vs. closed eyes. Interestingly, saccadic peak velocities were found to be lower in the presence of faces with direct gaze rather than closed eyes (Experiment 1). This effect emerged even in the presence of non-human primate faces (Experiment 2), and no differences between direct gaze and closed eyes emerged when the faces were presented inverted rather than upright (Experiment 3). Overall, these findings suggest that eye contact can have an impact on the saccadic generation system.

Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention

DOI:10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.001205 URL [本文引用: 1]

Object-based attention: Shifting or uncertainty?

DOI:10.3758/APP.72.7.1743 URL [本文引用: 3]

Shifting visual attention between objects and locations: Evidence from normal and parietal lesion subjects

DOI:10.1037/0096-3445.123.2.161 URL [本文引用: 2]

Eye contact detection in humans from birth

Making eye contact is the most powerful mode of establishing a communicative link between humans. During their first year of life, infants learn rapidly that the looking behaviors of others conveys significant information. Two experiments were carried out to demonstrate special sensitivity to direct eye contact from birth. The first experiment tested the ability of 2- to 5-day-old newborns to discriminate between direct and averted gaze. In the second experiment, we measured 4-month-old infants' brain electric activity to assess neural processing of faces when accompanied by direct (as opposed to averted) eye gaze. The results show that, from birth, human infants prefer to look at faces that engage them in mutual gaze and that, from an early age, healthy babies show enhanced neural processing of direct gaze. The exceptionally early sensitivity to mutual gaze demonstrated in these studies is arguably the major foundation for the later development of social skills.

Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses

DOI:10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 URL [本文引用: 1]

An investigation of attention allocation during sequential eye movement tasks

DOI:10.1080/713755838 URL [本文引用: 1]

The eyes have it! Reflexive orienting is triggered by nonpredictive gaze

DOI:10.3758/BF03208827 URL [本文引用: 1]

Attentional effects of counterpredictive gaze and arrow cues

DOI:10.1037/0096-1523.30.2.319 URL [本文引用: 1]

Gaze cueing of attention: Visual attention, social cognition, and individual differences

DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.694 URL [本文引用: 1]

Resolving conflicting views: Gaze and arrow cues do not trigger rapid reflexive shifts of attention

DOI:10.1080/13506285.2013.775209 URL [本文引用: 1]

The effects of genuine eye contact on visuospatial and selective attention

DOI:10.1037/xge0000199 URL [本文引用: 1]

The influence of object similarity on real object-based attention: The disassociation of perceptual and semantic similarity

DOI:10.1016/j.actpsy.2020.103046 URL [本文引用: 2]

The measurement of detection superiority of direct gaze affected by stimuli component information

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2013.01217 URL [本文引用: 1]

刺激特征信息影响直视探测优势测量

One step ahead: The perceived kinematics of others' actions are biased toward expected goals

DOI:10.1037/xge0000126 URL [本文引用: 1]

The influence of gazer and observer factors on gaze perception

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2021.00238 URL [本文引用: 1]

注视者及观察者因素对注视知觉的影响

Early face processing specificity: It’s in the eyes!

DOI:10.1162/jocn.2007.19.11.1815 URL [本文引用: 1]

Serial grouping of 2D-image regions with object-based attention in humans

DOI:10.7554/eLife.14320 URL [本文引用: 2]

The specific cognitive and neural mechanisms of social attention

社会性注意的特异性认知神经机制

Attentional shift by eye gaze requires joint attention: Eye gaze cues are unique to shift attention

DOI:10.1111/j.1468-5884.2011.00470.x URL [本文引用: 2]

Gaze and eye contact: A research review

Dimensions of perception: 3D real-life objects are more readily detected than their 2D images

DOI:10.1177/09567976211010718 URL [本文引用: 2]

Attention samples stimuli rhythmically

DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.054 URL [本文引用: 1]

Attention capture by faces

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2007.07.012 URL [本文引用: 1]

The differential effects of reward on space-and object-based attentional allocation

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5575-12.2013 URL [本文引用: 1]

Individual differences in the temporal dynamics of object-based attention

DOI:10.1167/jov.21.9.1953 URL [本文引用: 1]

Object-based attention in real-world scenes

DOI:10.1037/xge0000060 URL [本文引用: 1]

Revealing the mechanisms of human face perception using dynamic apertures

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2017.08.001 URL [本文引用: 1]

Influence of head orientation on perceived gaze direction and eye-region information

Visually induced inhibition of return affects the audiovisual integration under different SOA conditions

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2019.00759 URL [本文引用: 1]

不同SOA下视觉返回抑制对视听觉整合的调节作用

Orienting of attention

DOI:10.1080/00335558008248231 URL [本文引用: 1]

Fractionating the stare-in-the-crowd effect: Two distinct, obligatory biases in search for gaze

DOI:10.1037/xhp0000655 URL [本文引用: 2]

Is there a direct link between gaze perception and joint attention behaviours? Effects of gaze contrast polarity on oculomotor behaviour

DOI:10.1007/s00221-009-1706-8

PMID:19183970

[本文引用: 1]

Previous studies have found that attention is oriented in the direction of other people's gaze suggesting that gaze perception is related to the mechanisms of joint attention. However, the role of the perception of gaze direction on joint attention has been challenged. We investigated the effects of disrupting gaze perception on the orienting of observers' attention, in particular, whether orienting to gaze direction is affected by the disruptive effect of negative contrast polarity on gaze perception. A dynamic distracting gaze was presented to observers performing an endogenous saccadic task. Gaze perception was manipulated by reversing the contrast polarity between the sclera and the iris. With positive display polarity, eye movement recordings showed shorter saccadic latencies when the direction of the instructed saccade matched the direction of the distracting gaze, and a substantial number of erroneous saccades towards the direction of the perceived gaze when the latter did not match the instruction. Crucially, such effects were not found when gaze contrast polarity was reversed and gaze perception was impaired. These results extend previous studies by demonstrating the existence of a direct link between joint attention and the perception of gaze direction, and show how orienting of attention to other people's gaze can be suppressed.

Attentional spreading in object-based attention

Taking control of reflexive social attention

Direct gaze captures visuospatial attention

DOI:10.1080/13506280444000157 URL [本文引用: 1]

Object-based attention: Strategy versus automaticity

DOI:10.1002/wcs.1162 URL [本文引用: 3]

Object-based attention: Strength of object representation and attentional guidance

DOI:10.3758/PP.70.1.132 URL [本文引用: 3]

Shaping attention with reward: Effects of reward on space and object-based selection

DOI:10.1177/0956797613490743

PMID:24121412

[本文引用: 1]

The contribution of rewarded actions to automatic attentional selection remains obscure. We hypothesized that some forms of automatic orienting, such as object-based selection, can be completely abandoned in favor of a reward-maximizing strategy. In the two experiments reported here, we presented identical visual stimuli to observers while manipulating what was being rewarded (targets in different locations from the cue or in random object locations) and the type of reward received (money or points). We found that reward alone, not the objects, guides attentional selection and thus entirely predicts behavior. These results suggest that guidance of selective attention, although automatic, is flexible and can be adjusted in accordance with external nonsensory reward-based factors.

Configural and contextual prioritization in object-based attention

DOI:10.3758/BF03196566 URL [本文引用: 3]

Visual search efficiency is greater for human faces compared to animal faces

DOI:10.1027/1618-3169/a000263 URL [本文引用: 1]

Different temporal dynamics of object-based attentional allocation for reward and non-reward objects

Are you looking at me? Impact of eye contact on object-based attention

DOI:10.1037/xhp0000913 URL [本文引用: 6]

Eyes that bind us: Gaze leading induces an implicit sense of agency

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2017.12.011 URL [本文引用: 2]

Eye contact perception in the west and east: A cross-cultural study

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0118094 URL [本文引用: 1]

Object-based attention in chimpanzees

DOI:10.1016/j.visres.2010.01.003 URL [本文引用: 1]

Visual attention: A rhythmic process?

The typical advantage of object-based attention reflects reduced spatial cost

The influence of dynamic and static gaze-cueing upon attention shift: Role of movement cues

动态和静态注视线索对注意转移的影响:运动线索的作用

The impact of monetary stimuli on object-based attention

DOI:10.1111/bjop.12418 URL [本文引用: 2]

Twofold advantages of face processing with or without visual awareness

DOI:10.1037/xhp0000915 URL [本文引用: 1]