1 引言

眼睛注视(eye gaze)在我们的社会交往中扮演着重要的角色。在不同的社会情境下, 眼睛注视具有提供信息、调节互动、表达亲密、实施社会控制以及促进服务与任务目标完成的功能(Kleinke, 1986)。注视知觉即对他人注视方向的知觉, 是我们加工处理他人注视信息的前提。从形态学上来讲, 人类的眼睛相对于其他物种而言有着独特的结构:深色的虹膜被大面积的白色巩膜所包围(Kobayashi & Kohshima, 1997)。眼睛的这一形态能够向他人揭示我们的注视方向, 从而促进了人类种族内部之间的信息交流与相互合作(Kobayashi & Kohshima, 2001; Kret & Tomonaga, 2016; Holler & Levinson, 2019)。一些研究者认为, 人眼独特的虹膜-巩膜的几何构造使我们能够十分准确地判断他人注视方向(Cline, 1967; Gibson & Pick, 1963; Gale & Monk, 2000; Symons et al., 2004)。而随着后续研究的深入, 研究者发现个体对他人注视方向的判断事实上受到了很多因素的影响, 但在以往综述中并没有深入地对这些因素进行整合与分析。因此本文从眼神沟通中的不同角色定位——注视者与观察者这一视角出发, 对这一领域相关的理论及实证研究进行梳理整合, 并评述与探究当前研究存在的问题及未来的研究方向。在本文中, 我们将眼睛注视的发出者称之为注视者(gazer), 注视的接受者称之为观察者(gazee)。

2 注视者因素对注视知觉的影响

2.1 眼部及头部的物理特征对注视知觉的影响

2.1.1 眼睛物理特性对注视知觉的影响

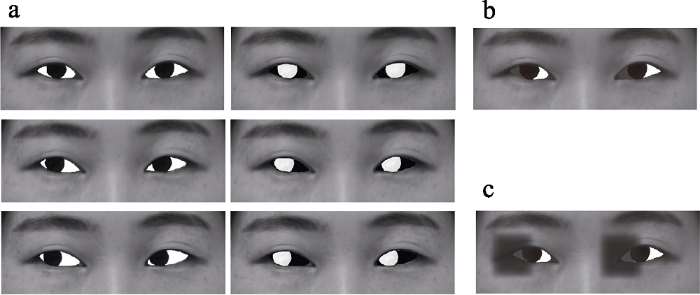

我们在对他人注视方向进行判断时, 最直接的线索就是眼睛本身。通过比较多种灵长类动物的眼睛结构, Kobayashi和Kohshima (1997)发现人类的眼睛具有独特的虹膜-巩膜比例且其形状轮廓在水平方向上拉长。人眼的这些特征为知觉注视方向提供了几何结构和明度线索(Anstis et al., 1969; Ando, 2002, 2004; Olk et al., 2008; Doherty et al., 2015)。几何结构线索是指在判断注视方向时依赖于虹膜在巩膜中的位置信息。可以理解的是, 个体对他人注视方向的判断很大程度上依赖于这一线索(Anstis et al., 1969)。明度线索是指虹膜与巩膜的高度暗明对比信息, 能使得我们更迅速准确地从眼睛的几何结构中提取他人注视方向的信息。研究发现, 在不改变眼睛几何结构的前提下, 虹膜与巩膜的对比度极性的翻转会显著降低个体对注视方向判断的准确性(图1a) (Ricciardelli et al., 2000; Olk et al., 2008)。除此以外, 眼部及其周围皮肤的亮度信息也会影响到个体对他人注视方向的判断。Ando (2002, 2004)发现改变巩膜一侧的亮度会导致个体知觉到的注视方向向较暗的一侧偏移。例如, 当直视前方的眼睛右侧巩膜变暗时, 个体对该注视方向判断会向右侧偏移(图1b)。若眼部一侧被阴影覆盖, 个体对注视方向的判断也会有一定程度的偏移(图1c)。这些研究证据也都说明视觉系统遵循一个固定的规则来对他人注视方向进行判断, 即我们会更倾向于将眼睛中更暗的部分当做他人进行注视的部分(Ricciardelli et al., 2000)。Ando (2002)认为, 注视知觉的明度机制由低空间频率信息(low-spatial-frequency information)所支配, 发生迅速但粗糙; 而几何结构则是由高空间频率信息(high-spatial-frequency information)所支配, 发生缓慢但精细。来自发展心理学的证据也支持这两种注视加工机制并发现个体在使用这两种线索时所具有的年龄差异性。Doherty等人(2015)采用注视追随(gaze following)的实验范式探讨了不同年龄段的儿童对于具有不同线索信息的注视面孔的加工, 结果发现2~3岁的儿童的注视追随主要依赖于亮度线索, 当使用缺少这一信息的刺激材料时, 如简笔画的人脸, 被试的注视追随行为也显著地减少了。大约从3岁开始, 个体开始利用几何线索并综合亮度线索对注视方向进行判断。

图1

图1

亮度线索对注视方向的判断的影响(示例)。(a)眼睛内部虹膜与巩膜的对比度进行极性翻转。(b)直视前方的眼睛右侧虹膜变暗。(c)直视前方的眼睛一侧被阴影覆盖。

2.1.2 刺激材料类型对注视知觉的影响

在以往注视知觉研究的相关文献中, 大多数的研究使用了人脸或眼睛的图片作为刺激材料。除此以外, 研究还使用了包括线条画(Friesen & Kingstone, 1998; Ristic et al., 2002)、计算机生成图片(Schilbach et al., 2006; Lobmaier et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2017)、动态视频(Kuzmanovic et al., 2009; Pelphrey et al., 2004)、肖像画(Kesner et al., 2018)以及真实人脸(Pönkänen et al., 2011; Lyyra et al., 2017)作为刺激材料。但这些不同类型的刺激在生态效度、社会线索的丰富性以及观众效应(Audience Effect)的激发上都具有较大差异(Hamilton, 2016)。Hietanen及其同事的一系列研究表明, 以图片及真人形式呈现的注视刺激会引起不同的行为和生理反应(Hietanen et al., 2008; Pönkänen et al., 2010, 2011)。例如, Pönkänen等人(2010)使用真人和图片刺激材料探讨了个体对于不同注视方向的脑电反应, 结果发现, 直视相对于斜视和闭眼刺激来说诱发了一个更大的N170和早期后部负电位(Early Posterior Negativity, EPN), 但这一效应仅在真人刺激的条件下发现, 而在图片条件下则没有发现这一效应。在使用动态视频刺激的研究中也发现了同样的效应(Conty et al., 2007)。另一项研究则比较了对直视条件下的真人、仿真假人及其对应的照片的脑电反应, 发现早期时间窗(125~170和170~230 ms)中的脑电波幅对刺激物的性质(真人和仿真假人)敏感, 而对刺激物呈现的形式不敏感(照片或实体) (Debruille et al., 2012)。脑成像的研究也报告出不同刺激材料所引发不同脑结构的激活。Kesner等人(2018)使用了不同绘画风格的肖像画让被试判断画中人物的注视方向并同时扫描其大脑, 结果发现与线描性风格(linear style, 注重运用线条与轮廓写实)的肖像画相比, 绘画性风格(painterly style, 运用抽象色彩较少地写实)的肖像画对枕叶内侧和皮下结构, 包括距状裂(calcarine fissure), 楔状叶(cuneus), 舌状回(lingual)和梭状回(fusiform gyri)的激活程度更高。这些研究结果表明, 在注视行为相关任务中, 不同刺激材料条件下会引发不同的大脑活动。虽然尚未有直接数据表明不同的刺激材料会影响到对他人注视方向的判断, 但是在考虑到不同刺激材料在生态性及信息的丰富性上的差异, 我们推测刺激材料类型也可能会影响个体对他人眼睛注视的加工。例如在Kluttz等人(2009)的综述中, 研究者提到了Kappa角这一眼睛的生理概念(即光轴与视轴的夹角:光源与黄斑中心凹的连线为视轴; 角膜中心和瞳孔中心的连线为光轴)。Kappa角的大小因人而异, 通常在双眼之间对称且为正性角度, 这意味着注视者的瞳孔轴通常指向被注视对象的颞侧。计算机生成或线条示意图等二维图片相较于真实的三维刺激则缺乏了这一信息, 而这一特征的缺失可能使得二维图片在注视方向的表达上存在误差从而影响观察者的感知。综上所述, 刺激材料的不同在注视方向信息的表达及观察者感知时的神经加工过程上存在差异, 未来的研究有必要进一步探讨刺激材料类型在注视知觉中所起到的作用, 例如同一实验中的不同刺激材料是否会导致实验结果不一致?二维图片刺激能否代替真人刺激来模拟注视者的注视方向?针对这些问题的探索有利于提高今后研究中实验材料的标准化以及实验的整体效度。

2.1.3 头部及身体朝向对注视知觉的影响

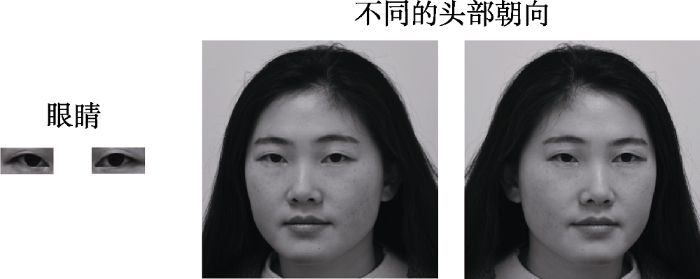

Wollaston (1824)首先发现我们对于他人注视方向的判断不仅依赖于眼部几何结构线索, 同时也会受到被观察者头部朝向的影响。如图2所示, 左侧图片上的眼睛似乎是直视前方, 而右侧的图片由于注视者头部向左偏, 使得其眼睛看起来似乎是看向观察者右侧。但当遮住人脸其他部位仅仅只露出眼睛的时候, 我们会发现两张图片的眼睛注视方向是一样, 这一现象被称之为沃拉斯顿效应(the Wollaston effect)。此后, 有大量的实证研究也显示出头部朝向会影响个体对他人注视方向的判断(Gibson & Pick, 1963; Cline, 1967; Anstis et al., 1969; Langton, 2000; Todorović, 2006; Moors et al., 2016; Balsdon & Clifford, 2017)。Langton (2000)采用类Stroop范式考察了头部朝向与注视方向之间的相互影响。研究者给被试呈现头部朝向和注视方向一致或不一致的人脸图片, 在一些条件下要求被试判断头部朝向, 另一些条件下要求被试判断注视方向。结果发现, 无论是判断头部朝向还是判断注视方向, 被试在头部朝向和注视方向不一致的条件下的反应时显著慢于一致的条件。那么头部朝向如何影响注视方向的判断呢?以往的研究报告出两种效应:超射效应(overshoot effect)和牵引效应(towing effect) (Langton et al., 2004)。前者是指知觉到的注视方向向头部朝向相反的方向偏移的现象(Noll, 1976; Masame, 1990; Todorović, 2006, 2009)。例如, 当头部向右偏转30°的面孔注视着你的眼睛的时候, 你可能会觉得他注视着你的左肩。后者是指知觉到的注视方向向头部朝向相同的方向偏移的现象, 如前面所提到的沃拉斯顿效应(Maruyama & Endo, 1983, 1984; Sheldon et al., 2014)。由上可知, 在注视方向与头部朝向不一致的情况下, 这两种效应事实上预测出不一样的结果。但到目前为止, 尚未有文献对两种效应发生的具体条件进行深入探讨, 通过对现有文献的整理也难以获取这两种效应的具体发生机制, 所以我们认为未来的研究需要从刺激材料、被试的个体差异角度对这一问题进行补充。

图2

图2

沃拉斯顿效应:人们感知到的肖像凝视方向不仅取决于虹膜的位置, 还取决于头部的朝向。左右两张脸的眼睛是一样的, 但是头部的转动使两组眼睛看起来像是在看不同的方向。

除头部朝向外, 注视者身体的朝向也会影响观察者对其注视方向的判断(Perrett et al., 1992; Hietanen, 2002; Seyama & Nagayama, 2005; Moors et al., 2016)。Moors等人(2016)给被试呈现具有不同头部朝向(注视方向)及身体朝向的图片, 结果也发现超射效应, 即个体所知觉到的注视方向会向身体朝向的反方向偏移。另外也有研究报告出面部物理信息, 如鼻子的角度(Langton et al., 2004)、眉毛的位置(Watt et al., 2007)以及虹膜的颜色(West, 2011)对注视知觉的影响。综上所述, 这些研究结果说明了个体在加工他人眼睛注视时并不仅仅依赖眼睛的局部特征信息, 同时也会整合注视者其他面部及身体背景信息, 且会受到其他背景信息的影响。

2.2 面孔情绪与吸引力对注视知觉的影响

2.2.1 面孔表情对注视知觉的影响

面孔表情作为一种重要的社会信号, 能够传达出个体的情绪状态, 同时也会引发观察者的情绪及动机反应。以往的研究揭示出了面孔表情与注视方向存在相互影响的关系(Adams & Kleck 2003, 2005; Adams & Franklin 2009)。Adams和Franklin (2009)的研究发现注视知觉会受到面孔表情的影响, 他们在实验中要求被试对不同情绪面孔的注视方向进行判断, 结果发现被试对于在恐惧面孔条件下的斜视反应更快更准确, 而对于在愤怒面孔条件下的直视反应更快更准确。作者使用“共享信号”理论(shared signal hypothesis)对这一结果进行解释, 这一理论认为, 注视者的面孔表情与注视方向都显示了其趋近或者回避的动机倾向, 当面孔表情与注视方向所展示的动机倾向相一致的时候, 如快乐/愤怒面孔与直视相结合或悲伤/恐惧与斜视相结合时, 则会促进对不同注视方向的加工。Lobmaier等人一系列的研究采用了注视锥(gaze cone)作为测量指标探讨了情绪面孔对自我指向的注视知觉的影响(Lobmaier et al., 2008; Lobmaier & Perrett, 2011; Lobmaier et al., 2013)。在这些研究中, 他们给被试呈现了一系列具有不同情绪面孔(快乐、恐惧、愤怒及中性情绪)及注视方向(直视、向左及向右偏转2°, 4°, 6°, 8°和10°)的人脸图片, 并要求被试判断该面孔是否在注视他们。通过计算不同情绪面孔条件下的注视锥, 即计算出一个被试有50%的概率将其判断为直视的注视角度值, 研究发现相较于恐惧、愤怒及中性情绪面孔而言, 快乐面孔条件下有着更宽的注视锥, 即被试将更大偏转的注视方向判断为直视。作者认为这一结果能够在“自我参照的积极偏向” (self-referential positivity bias)的理论框架下进行解释, 即个体具有一种对于自我的积极偏向, 这种认知方式反映出个体以自我为中心的态度并且有利于个体自尊的健康发展。因此将他人的快乐解释为指向自身意味着一种正性的强化和社会奖励, 反之将他人的负性情绪解释为与自己无关则体现出一种对个体自尊的保护。

根据Adams和Kleck (2003, 2005)所提出的“共享信号”理论, 面孔情绪与注视方向的加工过程是相互作用, 相互影响的。但是有些证据似乎并不支持这一结论。Graham和LaBar (2007, 2012)在综合前人研究的基础上认为面孔情绪与注视方向之间的相互影响并不是必然的, 其发生是需要一定条件的, 即当目标本身所包含的信息不足以完成当前任务的情况下, 个体则会借助其他相关信号的信息来做出判断。他们的研究发现, 当刺激面孔传达出明确的情绪类别的时候, 注视方向并不影响面孔情绪的加工(实验1和2); 而随着面孔情绪的可辨识度降低, 注视方向对面孔情绪加工的影响也逐渐显现出来(实验3和4)。因此, 依据这一结果与作者所提出的理论解释, 那么当注视方向辨识度处于较高水平下, 面孔情绪对注视方向的影响可能也并不是必然的。

2.2.2 面孔吸引力对注视知觉的影响

面孔吸引力是人类面孔所包含的另一个重要的社会信息。作为观察者, 我们对于高吸引面孔具有积极的偏向并更倾向于接近这些个体(Langlois et al., 2000)。这一偏好背后的心理机制在于高吸引力的面孔对观察者来说是一种奖励从而能够诱发其积极愉悦的情绪体验(Aharon et al., 2001)。研究表明, 高吸引力面孔的奖励效应事实上受到眼睛注视的调节。在不同注视方向条件下, 面孔吸引力的高低能够调节观察者腹侧纹状体(ventral striatum)中多巴胺神经元投射区的活跃程度, 而这一区域的活跃程度则与奖励预测密切相关(Kampe et al., 2001)。在直视的条件下, 面孔吸引力与该区域的活跃程度成正相关, 而在斜视的条件下, 面孔吸引力与该区域的活跃程度成负相关。以往的研究也揭示出面孔吸引力对于注视知觉的影响。Kloth等人(2011)通过给被试呈现了具有不同注视方向的高吸引力和低吸引力面孔后发现, 高吸引力的面孔增加了观察者感知眼神接触的倾向, 即观察者更倾向于将高吸引力面孔判断为看向自己。作者认为这一结果同样也能够在“自我参照的积极偏向”的理论框架下进行解释, 即个体会更倾向于将高吸引力面孔——这一具有奖励意义也更愉悦的刺激判断为指向自身以正性强化并维护个体的自尊。因此我们可以推断面孔吸引力对注视知觉的影响作用于个体的奖赏系统, 即高吸引力的面孔给个体带来了更多的正强化, 在未来的研究中可对这一假设进行验证与补充。

3 观察者因素对注视知觉的影响

3.1 观察者心理障碍对注视知觉的影响

从观察者的角度来说, 观察者本身的心理障碍会影响到其对于他人注视方向的判断。在前人的研究中重点探讨了具有以下三种心理障碍的个体的注视知觉, 即社交焦虑障碍(Social Anxiety Disorder, SAD)、自闭症谱系障碍(Autism Spectrum Disorder, ASD)以及精神分裂症(Schizophrenia, SCZ)。

3.1.1 社交焦虑障碍与眼睛注视

SAD是一种由于社交情景所引发的极度不适或忧虑的精神疾病, 其行为表现为对于社交情景的强烈恐惧和回避(DSM-V, American Psychiatric Association, 2013)。既然眼睛注视作为一种重要的社会交往信号, 那么SAD个体与健康个体对于眼睛注视的加工方式上是否存在着不同?研究通过比较SAD与健康对照组的视觉扫描路径发现, SAD个体对于他人的直视面孔, 特别是眼部区域, 采用了回避的策略, 其具体表现为患者对于眼部区域更少的注视次数和更短的注视持续时间(Horley et al., 2003, 2004)。Moukheiber等人(2010)的研究也支持这一结果, 他们发现社交焦虑的严重程度与注视的回避程度之间存在一个显著的正相关关系, 并且这一相关在具有社会威胁的面孔情绪(即愤怒和厌恶)上最为明显。由此可见, 从注视行为上来说, SAD个体会倾向于回避眼睛直视这一显示注视者趋近动机的社会信号。当要求其关注他人眼部区域时, SAD个体会如何知觉他人的注视方向呢?Gamer等人(2011)采用心理物理法的方法测量了观察者的注视锥。在研究中, 他们要求被试转动一个三维虚拟头部的眼睛直至为直视自己。结果发现, 和控制组相比, SAD个体具有更宽的注视锥, 即他们会倾向于将更大偏转的注视方向判断为直视, 且注视锥的大小与社交焦虑症状的严重程度呈正相关。但是, 这一效应仅在有另一个三维虚拟头部(实验中设置为社交情景中的旁观者)同时呈现的时候产生。这一结果表明, 在多人社交的场景下, SAD患者的注视知觉会受到影响。而作者将这一结果归因于SAD个体对不同社会信息加工偏向(information-processing biases)。由于SAD个体对于更倾向于以一种负性的方式去解释不确定的事件且对负性刺激更加敏感(Chen & Drummond, 2008), 而在社交情景中, 直视作为趋近动机的社交信号, 表达了注视者的社交意图与接近动机, 因此SAD个体可能将其视为是一种负性的社会刺激也对其更加敏感, 倾向于将更大偏转的注视方向知觉为看向他们自己。另一项采用了三维虚拟面孔及真人面孔作为刺激材料的研究也报告出SAD个体与控制组相比具有更宽的注视锥, 而且该效应在真人面孔条件下更大(Harbort et al., 2013)。作者认为, 导致这一结果的原因可能是真人面孔相较于三维虚拟面孔能够诱发被试更高的唤醒度, 从而更能够激发个体对社交的恐惧。该研究还发现SAD个体在接受了认知行为疗法(Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, CBT)后, 除了其社交焦虑症状得以明显改善外, 其注视锥大小也变得与对照组无显著差异, 这说明对于社交焦虑症状的干预也会导致SAD个体注视知觉的正常化。一些使用非临床被试的研究也同样报告出类似的结果(Schulze et al., 2013; Jun et al., 2013; Bolt et al., 2014)。例如Schulze等人(2013)通过一项基于网络的研究发现自我报告的社交焦虑程度与他人注视的自我指向知觉(self-directed perception)呈正相关, 即社交焦虑高的个体更倾向于将他人的注视方向知觉为看向自己, 特别是对于负性(愤怒、恐惧)和中性面孔而言。作者认为, 这一结果也能够帮助我们更好的理解为什么SAD个体对于社交情境有着强烈的恐惧和回避, 原因之一可能是因为他们会过度的估计在社会情境中来自他人的审视和评价。

3.1.2 自闭症谱系障碍与眼睛注视

ASD是一类神经发育障碍, 其主要症状表现为社交障碍、沟通障碍以及重复刻板的行为模式(DSM-V, American Psychiatric Association, 2013)。其中, 对他人注视加工能力的受损通常被认为是ASD个体社交及沟通障碍症状的核心驱动因素(Baron-Cohen, 1997)。在注视行为上, 相较于正常发育(typically developing, TD)个体而言, ASD个体会更少的注视他人的眼部区域, 更多的避免与他人建立眼神接触(eye contact) (Klin et al., 2002; Pelphrey et al., 2002; Riby & Hancock, 2009)。虽然ASD个体在自发的使用眼睛注视线索上存在着缺陷, 但这并不意味着他们完全无法正常加工他人的注视方向(Akechi et al., 2010)。研究发现, 当实验任务要求他们关注他人眼部并对其注视方向进行跟随或判断的时候, ASD个体的表现与TD个体并没有显著的差异(Baron-Cohen et al., 1995; Leekam et al., 1997; Kylliäinen & Hietanen, 2004; Senju et al., 2004; Swettenham et al., 2003)。一些研究者认为, ASD个体在注视知觉上的缺损可能并不表现在其对于他人注视方向的判断上, 而在于其能否正确使用注视线索来理解他人的意图和心理状态(Baron-Cohen et al., 1995; Leekam et al., 1998)。例如在一项研究中, 作者给儿童被试呈现看向四种不同糖果的卡通人脸图片, 然后询问被试该卡通人物会想要哪一颗糖果(Baron-Cohen et al., 1995)。结果发现, TD儿童通常会判断人脸看向的那颗糖果会是其想要的, 也就是说, TD儿童能够将注视者的注视行为与其心理活动联系起来, 并以此作为线索来推断他人的意图和目标。相反的, ASD儿童的选择则并没有受到卡通人物注视方向的影响。而在另一项仅判断他人注视方向的任务中, ASD与TD儿童的表现却没有差异。由于其不能合理的使用眼睛注视这一社会性线索, ASD个体在社会互动中无法捕捉到许多由他人眼部所传递出来的重要信息, 例如他人的意向等心理状态(Baron-Cohen, 1997), 引发联合注意(joint attention)以及话轮转换(turn-taking)的信号等(Böckler et al., 2014)。最近的一项研究采用了适应后效的范式来考察自闭症患者的注视知觉编码(Palmer et al., 2018)。注视方向的适应后效指当适应了某一注视方向后, 个体对接下来呈现的注视方向的判断向相反方向偏转的现象(Calder et al., 2007; Jenkins et al., 2006)。结果发现ASD患者与正常人在神经反应的正常化和适应上并没有显著差异, 作者认为这一结果可能表明ASD患者对他人注视的反应差异与更高层次的认知功能有关, 如在社会情境中对他人注视方向的解释或对他人注视位置的自发跟随, 而ASD患者的低层次感觉编码是正常的。

也有研究认为ASD个体在利用眼睛注视线索能力上的缺损是由于其与TD个体在眼睛注视的加工方式上存在差异。例如, 一项研究利用直视面孔和斜视面孔的搜索不对称性(search asymmetry)探讨了ASD和TD儿童的注视知觉(Senju et al., 2008)。这种搜索的不对称性是指, 相比于斜视面孔, 我们会在目标搜索时更快地探测到直视面孔, 这一现象也被称之为“人群中的凝视效应” (the stare-in-the-crowd effect) (von Grünau & Anston, 1995; Senju et al., 2005; Conty et al., 2006)。这一效应产生的原因是由于直视比斜视能够更快地捕获观察者的注意(Senju & Hasegawa, 2005)。在Senju等人(2008)的研究中, 被试需要在多个干扰刺激中又快又准确地探测到目标刺激并做出反应, 即从多个斜视眼部/面孔刺激中探测到直视, 或者从多个直视眼部/面孔刺激中探测到斜视。结果显示, 在正立面孔的条件下, ASD儿童和TD儿童的表现没有区别, 均呈现出“人群中的凝视效应”。但当面孔倒置的时候, 研究发现TD儿童的表现受到了面孔倒置的影响, 即他们对直视的搜索速度显著地变慢了, 而ASD儿童的表现并未受到面孔倒置的影响。作者认为, 这一研究结果表明ASD儿童更多使用特征信息(featural information)来检测眼睛注视, 而TD儿童则更多使用构形信息(configural information)来检测眼睛注视(Senju et al., 2005; Senju et al., 2008)。这样的加工方式也导致ASD个体在对注视信息与其他社会性信息的整合上存在着缺损(Pelphrey et al., 2005; de Jong et al., 2008; Akechi et al., 2009; Akechi et al., 2010)。例如, Akechi等人(2009, 2010)发现, 动机倾向相一致的面孔情绪和注视方向(如快乐/愤怒面孔与直视或悲伤/恐惧与斜视)能够促进TD儿童对于他人面孔情绪的加工, 而ASD儿童对他人面孔情绪的判断并不受到注视方向的影响。

到目前为止, 仅有一项研究考察了个体的自闭症特质对于自我指向的注视知觉的影响。在该研究中, Matsuyoshi等人(2014)通过掩蔽的方式快速的向非临床被试呈现具有不同注视方向(直视、向左及向右偏转10°, 20°和30°)的人脸图片, 并让被试判断人脸图片是否在注视他们。结果发现, 男性被试在自闭谱系量表(Autism Spectrum Quotient, ASQ)上的得分与其将他人的注视方向感知为直视的角度范围呈负相关, 即自闭程度越高的被试会更少地将他人的注视方向判断为注视向自己。

3.1.3 精神分裂症与眼睛注视

SCZ是一种严重的精神疾病, 通常伴有严重影响社会功能的社会认知缺陷(Bellack et al., 1990; Corcoran, 2001)。眼睛注视作为一种重要的社会交往信号, 以往的研究也考察了SCZ患者对于他人眼睛注视的加工。在注视行为上, 研究一致发现, SCZ患者和健康对照组相比会更少地与他人进行眼神接触, 更倾向于回避来自他人的社交信号(Green & Phillips, 2004, Phillips & David, 1998)。而对于SCZ患者的注视知觉是否受损的问题, 以往的研究报告出不同的结果。一方面, 一些研究发现, SCZ患者比健康对照组更倾向于将他人的注视方向判断为直视, 且这种倾向性与其临床症状的严重程度呈正相关(Hooker & Park, 2005; Rosse et al., 1994; Tso et al., 2012)。另一方面, 也有一些研究并没有发现SCZ患者和正常个体在判断他人注视方向上的显著差异, 而这类研究的特征则是让被试判断明确的斜视方向(左、右) (Franck et al., 1998, 2002; Kohler et al., 2008)。通过对这两类研究的分析我们可以发现, 这些研究结果上的不一致可能是由于所使用的研究范式及任务不同导致的。这些差异性或许揭示了一个事实, 即SCZ患者注视加工的困难似乎与自我参照判断(self-referential judgment)的任务相关, 而不是方向性判断任务, 例如当判断他人注视方向是向左还是向右时, SCZ患者的表现与健康对照组并没有显著差异(Franck et al., 1998, 2002)。这说明SCZ患者可能保留了辨别他人注视方向的基本功能, 而在判断他人是否看向自己时存在的偏差可能与自我参照决策偏差或注视的精神状态归因这些更高层次的认知加工的损伤有关。这一推测也在最近的一项研究中得到了验证, Seymour等人(2016)使用了连续闪光抑制实验范式来探究SCZ患者对注视方向处理的无意识机制。结果表明, SCZ患者保留了对注视方向正常的早期无意识感知, 即与健康个体表现一致, 相比于转移目光的面孔, 更容易看到眼睛直视的面孔。这也意味着SCZ患者对注视方向的错误判断可能发生在注视加工过程的高层次认知阶段。

3.2 观察者当前状态对注视知觉的影响

3.2.1 情绪相关状态对注视知觉的影响

观察者当前的认知或情绪状态也会影响其对他人注视方向的判断。在前人的文献中考察了压力(stress)及社交排斥感(ostracism)这两种与情绪相关的状态对于注视知觉的影响。Rimmele和Lobmaier (2012)通过冷水压力测验(cold pressure stress test)的方法诱发被试的压力, 并要求被试判断一系列不同注视方向的面孔是否看向自己。结果发现, 与控制组相比, 压力组的注视锥更宽, 即该组个体将更大偏转的注视方向判断为直视。压力的产生是由于个体认为他们没有足够的资源来处理具有威胁性的情境(Cohen et al., 1983)。那么为了应对这样的情景, 个体会更加警觉与自我中心化, 会增强人们对可能与自身相关的刺激的注意力, 使得个体对这一刺激更加敏感, 即便是具有一些角度偏差的眼神也会将其判断为直视, 从而注视锥更大。因此, 也就导致了个体会倾向于更多地将他人的注视解释为看向自身。另一项研究显示, 个体当前的被排斥感也会影响其对于他人注视方向的判断(Lyyra et al., 2017)。研究发现, 与控制组相比, 社交排斥感组的注视锥更宽且报告出了更强烈的被注视感。作者认为产生这一结果的原因可能是由于被排斥的个体希望重新融入社会交往。

3.2.2 互动可能性的认知状态对注视知觉的影响

适应是指当持续暴露于某一刺激特征后, 个体对该刺激特征的反应性降低的现象。以往使用适应范式的研究主要集中在对于刺激物中低水平知觉特征的探讨, 如颜色(Webster, 1996)、朝向(Clifford, 2002)、运动(Anstis et al., 1998)等。Calder及其同事将适应范式运用于对于注视方向的研究上, 他们的研究结果报告出个体在注视知觉中的适应后效(aftereffect), 即当适应了某一注视方向后, 个体对接下来呈现的注视方向的判断向相反方向偏转的现象(Jenkins et al., 2006; Calder et al., 2008; Pellicano et al., 2013)。

在注视研究领域, 近年来的多项研究也揭示出个体对社会互动可能性的理解会影响其对他人注视方向的知觉和反应。Teufel等人(2009)利用适应后效的研究范式更进一步地考察了个体对他人能否看见自己的心理归因对注视方向判断的影响。在这一研究中, 实验者给被试呈现几段具有不同头部朝向的刺激模特的视频, 并让被试相信视频中的模特正在和他们进行实时互动。同时, 实验者告诉被试视频中的模特会佩戴两种眼镜, 一种是透明的, 另一种则是不透明的。研究结果发现, 当被试认为视频中的模特佩戴的是不透明的眼镜, 即无法看到被试自己的时候, 那么注视知觉中的后效则会显著减弱。在一系列使用真人刺激的研究中, 研究者同样操纵了个体对他人能否看见自己的心理归因(Myllyneva & Hietanen, 2015)。结果发现, 相较于斜视来说, 直视诱发了观察者更大的皮肤电(skin conductance)及心率减缓(heart rate deceleration)反应, 这些结果只在被试认为对方能看见自己的条件下出现。作者认为, 在认为对方能看见自己的条件下, 即对象具有社会互动可能性的时候, 观察者的心智化过程(mentalizing)会被激活并以第二人称的视角(second person perspective)来看待自己, 自我这一主体被体验为他人注意的客体, 从而导致了一系列的直视效应(Myllyneva & Hietanen, 2015)。值得一提的是, 前文所提的刺激材料类型也有可能通过影响互动可能性的认知状态从而影响个体对于注视方向的加工。

除被试的心理归因外, 个体对于社会互动的可能性的认知还体现于个体先前互动的经验中。在最近的一项研究中, 研究者首先让被试完成一个联合注视的学习任务(joint-gaze learning task), 在一种条件下, 刺激面孔与被试注视左侧或右侧的同一目标, 这些面孔称之为联合注视面孔(joint-gaze faces); 在另一种条件下, 刺激面孔注视被试注视的对侧目标, 这些面孔称之为非联合注视面孔(non-joint-gaze faces) (Edwards & Bayliss, 2019)。结果发现被试倾向于将联合注视面孔的更大偏转的注视方向判断为直视。作者认为, 这一结果的原因是由于学习阶段的互动经验影响到了个体对于即将发生的社交可能性的预期, 从而导致个体会知觉到更多的社交信号, 即直视。

由此可见, 个体对于注视方向等社会性刺激的知觉加工, 不仅仅是传统意义上所认为的由刺激驱动的反应, 同时也受到自上而下的调控, 与个体的心理理论(theory of mind)系统有着密切的联系, 受到如个体对注视者心理状态的归因、对社会互动可能性的评估等方面的影响。

3.3 注视知觉的性别、种族及文化差异

共情-系统化理论(empathizing-systemizing theory)区分了男女心理上的性别差异。该理论认为, 男性普遍更擅长高度规则化的系统性任务, 而女性普遍更擅长与心理状态归因及情绪相关的共情任务(Baron-Cohen, 2002; Baron-Cohen et al., 2003)。来自实证研究的证据也支持这一理论。研究发现, 相对于男性来说, 女性在注视方向的判断任务上表现更好(Ashwin et al., 2009), 能够更准确地从他人的眼睛注视中解读其心理状态(Baron-Cohen et al., 2001), 表现出更强的注视线索效应, 即对他人的注视方向有一个更快的追随(Bayliss & Tipper, 2005)。共情-系统化理论的一个延伸是对于ASD个体的“极端男性脑”的假设。该假设认为, ASD具有一种极端男性化的认知风格, 具有很低的共情水平以及高度的系统化水平(Baron-Cohen, 2002; Baron-Cohen & Hammer, 1997)。以往文献对ASD个体注视知觉的研究也证实了这一点, 在依据几何线索判断注视方向上保留完好, 但在利用注视推断心理意图以及联合其他社交信号时受到损伤(详见3.1.2)。

文化背景对注视知觉的影响可以从两个方面理解, 第一是具有不同文化背景的个体在注视加工方式上的差异性; 第二是个体对本种族面孔与其他种族面孔的眼睛注视加工之间的差异。从日常生活经验中我们能够发现, 作为交流的重要方式, 个体的注视行为及知觉极大的受到了文化背景的影响(Akechi et al., 2013)。一项调查研究发现, 西方文化背景比东方文化背景下的个体更注重在交谈中看着对方的眼睛(Argyle et al., 1986)。通过对于在各种情境下外显注视行为的分析, 一些研究也确实发现西方个体相对于东方个体来说会更多地看向对方的眼部区域, 而东方个体则会更多地看向对方面孔的中央区域即鼻子区域(Blais et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 2011)。不同文化背景下个体对他人注视的反应也具有一定的差异性, 例如一项研究对中西方不同文化背景下个体对直视及回避眼神的主观评价和生理唤醒进行探究, 结果发现, 日本被试与芬兰被试在心率上对直视的反应并没有显著差异, 但在主观评价上, 日本被试认为直视面孔更加负性。这一结果说明不同文化背景下的个体可能对不同的注视方向赋予了不同的含义(Akechi et al., 2013)。此外, 在注视知觉的研究中也发现了异族效应(Collova et al., 2017), 异族效应是指相对于本种族的面孔, 个体更难识别其他种族面孔(Hancock & Rhodes, 2008)。Collova等人的研究表明, 无论是白种人还是亚裔, 对其他种族面孔注视方向进行判断时都具有较低的敏感度。这表明, 在判断注视方向这一简单又重要的社交信号时, 我们也会受到种族间差异的影响, 也进一步说明了注视方向判断时更多社会性信息的参与。

4 总结与展望

眼睛是面孔的重要组成部分, 同时也是社会交往中的重要信息来源, 对他人注视方向的感知是人类的一项基本技能。本文从注视者与观察者两个角度出发, 探究注视者眼睛及面部物理特征、面孔情绪与吸引力及观察者心理障碍、当前状态对注视知觉的影响。研究发现, 注视知觉的过程不仅是由刺激驱动的反应, 同时也受到自上而下的调控, 与情绪-动机系统、心理理论系统以及认知归因等有着密切的联系。虽然对注视知觉的影响因素已做过大量的研究, 推进了这一领域的完善与发展, 但仍然有许多问题值得深入探究。

首先, 本文从注视者与观察者的角度分别探究了其对注视知觉的影响, 而这两部分内容应该是统一且不可分割的, 即在社交情景中注视者可以作为观察者, 观察者也可作为注视者。在今后的研究中, 可在实验范式与设计上进行创新, 进一步提升实验的互动性。例如, 在实验中设置真人被试代替计算机或模拟真人刺激, 实时监测自然条件下注视者与感知者的信息传递与互动、情绪表达、合作与竞争等方面对注视知觉的影响。此外, 这一方式也可通过多人同步交互式记录, 如超扫描(hyperscanning)技术来探究不同个体在信息沟通及目光互动过程中的神经活动的变化。

其次, 虽然注视者特征的诸多因素会对注视知觉产生影响, 但这些实验中注视者的刺激载体大多为简单的眼神或面孔图片, 刺激材料的使用也多种多样。在以往研究中发现了不同刺激材料在物理特征与对感知者的神经激活上存在差异, 不同的刺激材料类型可能影响注视知觉过程。为进一步探究刺激材料适用条件及其标准化问题, 未来可具体探究二维图片刺激与三维真人刺激在注视知觉上是否存在差异; 与此同时, 图片刺激材料的标准化上需要作进一步发展, 例如参照情绪图片库创建标准化注视方向图片库, 使刺激材料的使用上更加严格规范。

第三, 当前对注视知觉的研究大多在西方社会文化背景下进行, 而不同文化或者亚文化中个性化经验与动机存在差异, 进而对注视方向感知产生不同的认知加工机制。例如先前研究表明不同文化背景下的个体在对注视加工方式(Akechi et al., 2013)及对他人不同注视方向的反应(Argyle et al., 1986)上存在差异。而以往研究发现集体主义文化个体具有较高的人际趋近动机及社会性(Ashton et al., 2002)。因此, 对于集体主义文化背景下的个体来说, 注视所蕴含的意义及其对注视方向的感知是否与其他文化背景下的个体存在差异?例如在中国文化背景下直视所代表的趋近动机是否更加强烈?个体对直视的感知是否更加敏感?未来对注视知觉研究的本土化过程中应将文化或亚文化背景差异纳入自变量考虑, 进一步丰富这一领域的实证证据与理论解释。

最后, 在社交恐惧症、自闭症、精神分裂症等疾病的患者中发现了注视知觉损伤这一症状, 而焦虑症状缓解的同时注视知觉也趋于正常化(Harbort et al., 2013)。注视知觉既然可以作为一项病情诊断的重要指标, 那么注视知觉训练可否作为一种重要的行为训练方法运用于临床中来缓解患者的病情?目前针对这一领域的干预研究较少(Carbone et al., 2013; Baltazar & Conty, 2016), 但这些研究证明了这种干预方式具有一定的效果。因此, 未来研究可以以现有研究为基础, 开发科学的干预模式。首先, 参考现有心理或药物治疗方式进行前后测对照实验, 探究这一治疗方式的效果及适用群体。其次, 根据不同病症群体或所处阶段进行注视知觉训练方式的细化, 提出阶段性与个性化方案, 提升干预效果。最后, 深入探究这些干预方式的作用机制与适用范围, 建立完整的干预体系。

参考文献

Perceived gaze direction and the processing of facial displays of emotion

Effects of direct and averted gaze on the perception of facially communicated emotion

Influence of emotional expression on the processing of gaze direction

Beautiful faces have variable reward value: FMRI and behavioral evidence

Does gaze direction modulate facial expression processing in children with autism spectrum disorder?

The effect of gaze direction on the processing of facial expressions in children with autism spectrum disorder: An ERP study

DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.05.026

URL

PMID:20546762

[本文引用: 3]

This study investigated the neural basis of the effect of gaze direction on facial expression processing in children with and without ASD, using event-related potential (ERP). Children with ASD (10-17-year olds) and typically developing (TD) children (9-16-year olds) were asked to determine the emotional expressions (anger or fearful) of a facial stimulus with a direct or averted gaze, and the ERPs were recorded concurrently. In TD children, faces with a congruent expression and gaze direction in approach-avoidance motivation, such as an angry face with a direct gaze (i.e., approaching motivation) and a fearful face with an averted gaze (i.e., avoidant motivation), were recognized more accurately and elicited larger N170 amplitudes than motivationally incongruent facial stimuli (an angry face with an averted gaze and a fearful face with a direct gaze). These results demonstrated the neural basis and time course of integration of facial expression and gaze direction in TD children and its impairment in children with ASD.

Attention to eye contact in the West and East: Autonomic responses and evaluative ratings

Luminance-induced shift in the apparent direction of gaze

Perception of gaze direction based on luminance ratio

The perception of where a face or television 'portrait' is looking

The motion aftereffect

Cross-cultural variations in relationship rules

What is the central feature of extraversion? Social attention versus reward sensitivity

R. E. Lucas, E. Diener, A. Grob, E. M. Suh, and L. Shao (2000) recently argued that the core of the personality dimension of Extraversion is not sociability but a construct called reward sensitivity. This article accepts their argument that the mere preference for social interaction is not the central element of Extraversion. However, it claims that the real core of the Extraversion factor is the tendency to behave in ways that attract social attention. Data from a sample of 200 respondents were used to test the 2 hypotheses with comparisons of measures of reward sensitivity and social attention in terms of their saturation with the common variance of Extraversion measures. The results clearly showed that social attention, not reward sensitivity, represents the central feature of Extraversion.

Positive and negative gaze perception in autism spectrum conditions

A bias-minimising measure of the influence of head orientation on perceived gaze direction

Eye contact effects: A therapeutic issue?

Mindblindness: An essay on autism and theory of mind

The extreme male brain theory of autism

Are children with autism blind to the mentalistic significance of the eyes?

DOI:10.1111/bjdp.1995.13.issue-4 URL [本文引用: 3]

Is autism an extreme form of the "male brain"?

The systemizing quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism, and normal sex differences

DOI:10.1098/rstb.2002.1206

URL

PMID:12639333

[本文引用: 1]

Systemizing is the drive to analyse systems or construct systems. A recent model of psychological sex differences suggests that this is a major dimension in which the sexes differ, with males being more drawn to systemize than females. Currently, there are no self-report measures to assess this important dimension. A second major dimension of sex differences is empathizing (the drive to identify mental states and respond to these with an appropriate emotion). Previous studies find females score higher on empathy measures. We report a new self-report questionnaire, the Systemizing Quotient (SQ), for use with adults of normal intelligence. It contains 40 systemizing items and 20 control items. On each systemizing item, a person can score 2, 1 or 0, so the SQ has a maximum score of 80 and a minimum of zero. In Study 1, we measured the SQ of n = 278 adults (114 males, 164 females) from a general population, to test for predicted sex differences (male superiority) in systemizing. All subjects were also given the Empathy Quotient (EQ) to test if previous reports of female superiority would be replicated. In Study 2 we employed the SQ and the EQ with n = 47 adults (33 males, 14 females) with Asperger syndrome (AS) or high-functioning autism (HFA), who are predicted to be either normal or superior at systemizing, but impaired at empathizing. Their scores were compared with n = 47 matched adults from the general population in Study 1. In Study 1, as predicted, normal adult males scored significantly higher than females on the SQ and significantly lower on the EQ. In Study 2, again as predicted, adults with AS/HFA scored significantly higher on the SQ than matched controls, and significantly lower on the EQ than matched controls. The SQ reveals both a sex difference in systemizing in the general population and an unusually strong drive to systemize in AS/HFA. These results are discussed in relation to two linked theories: the 'empathizing-systemizing' (E-S) theory of sex differences and the extreme male brain (EMB) theory of autism.

The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism

Gaze and arrow cueing of attention reveals individual differences along the autism spectrum as a function of target context

An analysis of social competence in schizophrenia

Culture shapes how we look at faces

Effects of observing eye contact on gaze following in high-functioning autism

Faces in a crowd: High socially anxious individuals estimate that more people are looking at them than low socially anxious individuals

Separate coding of different gaze directions in the superior temporal sulcus and inferior parietal lobule

Visual representation of eye gaze is coded by a nonopponent multichannel system

DOI:10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.244 URL [本文引用: 1]

Teaching eye contact to children with autism: A conceptual analysis and single case study

Eye contact judgment is influenced by perceivers’ social anxiety but not by their affective state

Fear of negative evaluation augments negative affect and somatic symptoms in social-evaluative situations

Perceptual adaptation: Motion parallels orientation

The perception of where a person is looking

A global measure of perceived stress

A new other-race effect for gaze perception

When eye creates the contact! ERP evidence for early dissociation between direct and averted gaze motion processing

Searching for asymmetries in the detection of gaze contact versus averted gaze under different head views: A behavioural study

DOI:10.1163/156856806779194026

URL

PMID:17278526

[本文引用: 1]

Eye contact is a crucial social cue constituting a frequent preliminary to interaction. Thus, the perception of others' gaze may be associated with specific processes beginning with asymmetries in the detection of direct versus averted gaze. We tested this hypothesis in two behavioural experiments using realistic eye stimuli in a visual search task. We manipulated the head orientation (frontal or deviated) and the visual field (right or left) in which the target appeared at display onset. We found that direct gaze targets presented among averted gaze distractors were detected faster and better than averted gaze targets among direct gaze distractors, but only when the head was deviated. Moreover, direct gaze targets were detected very quickly and efficiently regardless of head orientation and visual field, whereas the detection of averted gaze was strongly modulated by these factors. These results suggest that gaze contact has precedence over contextual information such as head orientation and visual field.

Theory of mind and schizophrenia

N300 and social affordances: A study with a real person and a dummy as stimuli

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0047922

URL

PMID:23118908

[本文引用: 1]

Pictures of objects have been shown to automatically activate affordances, that is, actions that could be performed with the object. Similarly, pictures of faces are likely to activate social affordances, that is, interactions that would be possible with the person whose face is being presented. Most interestingly, if it is the face of a real person that is shown, one particular type of social interactions can even be carried out while event-related potentials (ERPs) are recorded. Indeed, subtle eye movements can be made to achieve an eye contact with the person with minimal artefacts on the EEG. The present study thus used the face of a real person to explore the electrophysiological correlates of affordances in a situation where some of them (i.e., eye contacts) are actually performed. The ERPs this person elicited were compared to those evoked by another 3D stimulus: a real dummy, and thus by a stimulus that should also automatically activate eye contact affordances but with which such affordances could then be inhibited since they cannot be carried out with an object. The photos of the person and of the dummy were used as matching stimuli that should not activate social affordances as strongly as the two 3D stimuli and for which social affordances cannot be carried out. The fronto-central N300s to the real dummy were found of greater amplitudes than those to the photos and to the real person. We propose that these greater N300s index the greater inhibition needed after the stronger activations of affordances induced by this 3D stimulus than by the photos. Such an inhibition would not have occurred in the case of the real person because eye contacts were carried out.

Attentional effects of gaze shifts are influenced by emotion and spatial frequency, but not in autism

Developmentally distinct gaze processing systems: luminance versus geometric cues

Seeing eye-to-eye: Social gaze interactions influence gaze direction identification

Gaze discrimination is unimpaired in schizophrenia

Gaze direction determination in schizophrenia

The eyes have it! Reflexive orienting is triggered by nonpredictive gaze

Where am I looking? The accuracy of video-mediated gaze awareness

Who is looking at me? The cone of gaze widens in social phobia

Perception of another person's looking behavior

Garner interference reveals dependencies between emotional expression and gaze in face perception

DOI:10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.296

URL

PMID:17516809

[本文引用: 1]

The relationship between facial expression and gaze processing was investigated with the Garner selective attention paradigm. In Experiment 1, participants performed expression judgments without interference from gaze, but expression interfered with gaze judgments. Experiment 2 replicated these results across different emotions. In both experiments, expression judgments occurred faster than gaze judgments, suggesting that expression was processed before gaze could interfere. In Experiments 3 and 4, the difficulty of the emotion discrimination was increased in two different ways. In both cases, gaze interfered with emotion judgments and vice versa. Furthermore, increasing the difficulty of the emotion discrimination resulted in gaze and expression interactions. Results indicate that expression and gaze interactions are modulated by discriminability. Whereas expression generally interferes with gaze judgments, gaze direction modulates expression processing only when facial emotion is difficult to discriminate.

Neurocognitive mechanisms of gaze-expression interactions in face processing and social attention

DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.01.019

URL

PMID:22285906

[本文引用: 1]

The face conveys a rich source of non-verbal information used during social communication. While research has revealed how specific facial channels such as emotional expression are processed, little is known about the prioritization and integration of multiple cues in the face during dyadic exchanges. Classic models of face perception have emphasized the segregation of dynamic vs. static facial features along independent information processing pathways. Here we review recent behavioral and neuroscientific evidence suggesting that within the dynamic stream, concurrent changes in eye gaze and emotional expression can yield early independent effects on face judgments and covert shifts of visuospatial attention. These effects are partially segregated within initial visual afferent processing volleys, but are subsequently integrated in limbic regions such as the amygdala or via reentrant visual processing volleys. This spatiotemporal pattern may help to resolve otherwise perplexing discrepancies across behavioral studies of emotional influences on gaze-directed attentional cueing. Theoretical explanations of gaze-expression interactions are discussed, with special consideration of speed-of-processing (discriminability) and contextual (ambiguity) accounts. Future research in this area promises to reveal the mental chronometry of face processing and interpersonal attention, with implications for understanding how social referencing develops in infancy and is impaired in autism and other disorders of social cognition.

Social threat perception and the evolution of paranoia

Gazing at me: The importance of social meaning in understanding direct-gaze cues

Contact, configural coding and the other-race effect in face recognition

The widening of the gaze cone in patients with social anxiety disorder and its normalization after CBT

DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2013.03.009

URL

PMID:23639302

[本文引用: 2]

Gaze plays a crucial role in social interactions. Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), which is associated with severe impairment of social interactions, is thus likely to exhibit disturbances of gaze perception. We conducted two experiments with SAD-patients and healthy control participants using a virtual head whose gaze could be interactively manipulated. We determined the subjective area of mutual gaze, the so-called gaze cone, and measured it prior to and after a psychotherapeutic intervention (Exp. 1). Patients exhibited larger gaze cones than control subjects. Exp. 2 varied the emotional expression of the virtual head. These data were validated using a real person (professional actor) as stimulus. Excellent reliability indices were found for our gaze cone measure. After Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, group differences in gaze cone width had disappeared. Emotional expressions were observed to modulate the gaze cone's width. Especially an angry expression caused the gaze cone to widen, possibly mediated by increased arousal. Finally, wider gaze cones in SAD-patients could be demonstrated for virtual and for real human heads confirming the ecological validity of virtual heads. The findings are of relevance for a more fine-grained understanding of perceptual processes in patients with SAD.

Social attention orienting integrates visual information from head and body orientation

DOI:10.1007/s00426-002-0091-8

URL

PMID:12192446

[本文引用: 1]

Subjects were asked to detect visual, laterally presented reaction signals preceded by head-body cue stimuli in a spatial cueing task. A head rotated towards the reaction signal combined with a front view of a body resulted in shorter reaction times in comparison to the front view of a head and body. In contrast, a cue showing the head and body rotated towards the reaction signal did not result in such a facilitation in reaction times. The results suggest that the brain mechanisms involved in social attention orienting integrate ventrally processed visual information from the head and body orientation. A cue signaling that the other person, in his or her frame of reference, has an averted attention direction shifts the observer's own attention in the same direction.

Seeing direct and averted gaze activates the approach-avoidance motivational brain systems

DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.029

URL

PMID:18402988

[本文引用: 1]

Gaze direction is known to be an important factor in regulating social interaction. Recent evidence suggests that direct and averted gaze can signal the sender's motivational tendencies of approach and avoidance, respectively. We aimed at determining whether seeing another person's direct vs. averted gaze has an influence on the observer's neural approach-avoidance responses. We also examined whether it would make a difference if the participants were looking at the face of a real person or a picture. Measurements of hemispheric asymmetry in the frontal electroencephalographic activity indicated that another person's direct gaze elicited a relative left-sided frontal EEG activation (indicative of a tendency to approach), whereas averted gaze activated right-sided asymmetry (indicative of avoidance). Skin conductance responses were larger to faces than to control objects and to direct relative to averted gaze, indicating that faces, in general, and faces with direct gaze, in particular, elicited more intense autonomic activation and strength of the motivational tendencies than did control stimuli. Gaze direction also influenced subjective ratings of emotional arousal and valence. However, all these effects were observed only when participants were facing a real person, not when looking at a picture of a face. This finding was suggested to be due to the motivational responses to gaze direction being activated in the context of enhanced self-awareness by the presence of another person. The present results, thus, provide direct evidence that eye contact and gaze aversion between two persons influence the neural mechanisms regulating basic motivational-emotional responses and differentially activate the motivational approach-avoidance brain systems.

Multimodal language processing in human communication

You must be looking at me: The nature of gaze perception in schizophrenia patients

Social phobics do not see eye to eye: A visual scanpath study of emotional expression processing

DOI:10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00180-9

URL

PMID:12464287

[本文引用: 1]

Clinical observation suggests that social phobia is characterised by eye avoidance in social interaction, reflecting an exaggerated social sensitivity. These reports are consistent with cognitive models of social phobia that emphasize the role of interpersonal processing biases. Yet, these observations have not been verified empirically, nor has the psychophysiological basis of eye avoidance been examined. This is the first study to use an objective psychophysiological marker of visual attention (the visual scanpath) to examine directly how social phobia subjects process interpersonal (facial expression) stimuli. An infra-red corneal reflection technique was used to record visual scanpaths in response to neutral, happy and sad face stimuli in 15 subjects with social phobia, and 15 age and sex-matched normal controls. The social phobia subjects showed an avoidance of facial features, particularly the eyes, but extensive scanning of non-features, compared with the controls. These findings suggest that attentional strategies for the active avoidance of salient facial features are an important marker of interpersonal cues in social phobia. Visual scanpath evidence may, therefore, have important implications for clinical intervention.

Face to face: Visual scanpath evidence for abnormal processing of facial expressions in social phobia

I thought you were looking at me: Direction-specific aftereffects in gaze perception

Cone of direct gaze as a marker of social anxiety in males

DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.05.020

URL

PMID:23769393

[本文引用: 1]

The fear of being scrutinised is a core feature of social anxiety disorder and socially anxious individuals overestimate being 'looked at'. A recent development in the vision sciences is a reliable psychophysical index of the range of eye gaze angles judged as being directed at oneself (Cone of Direct Gaze: CoDG). We tested the CoDG as a measure of

Psychology: Reward value of attractiveness and gaze

DOI:10.1038/35098149

URL

PMID:11595937

[本文引用: 1]

Faces are visual objects in our environment that provide strong social cues, with the eyes assuming particular importance. Here we show that the perceived attractiveness of an unfamiliar face increases brain activity in the ventral striatum of the viewer when meeting the person's eye, and decreases activity when eye gaze is directed away. Depending on the direction of gaze, attractiveness can thus activate dopaminergic regions that are strongly linked to reward prediction, indicating that central reward systems may be engaged during the initiation of social interactions.

Developing cultural differences in face processing

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01067.x

URL

PMID:21884332

[本文引用: 1]

Perception and eye movements are affected by culture. Adults from Eastern societies (e.g. China) display a disposition to process information holistically, whereas individuals from Western societies (e.g. Britain) process information analytically. Recently, this pattern of cultural differences has been extended to face processing. Adults from Eastern cultures fixate centrally towards the nose when learning and recognizing faces, whereas adults from Western societies spread fixations across the eye and mouth regions. Although light has been shed on how adults can fixate different areas yet achieve comparable recognition accuracy, the reason why such divergent strategies exist is less certain. Although some argue that culture shapes strategies across development, little direct evidence exists to support this claim. Additionally, it has long been claimed that face recognition in early childhood is largely reliant upon external rather than internal face features, yet recent studies have challenged this theory. To address these issues, we tested children aged 7-12 years of age from the UK and China with an old/new face recognition paradigm while simultaneously recording their eye movements. Both populations displayed patterns of fixations that were consistent with adults from their respective cultural groups, which 'strengthened' across development as qualified by a pattern classifier analysis. Altogether, these observations suggest that cultural forces may indeed be responsible for shaping eye movements from early childhood. Furthermore, fixations made by both cultural groups almost exclusively landed on internal face regions, suggesting that these features, and not external features, are universally used to achieve face recognition in childhood.

Perception of direct vs. averted gaze in portrait paintings: An fMRI and eye-tracking study

DOI:10.1016/j.bandc.2018.06.004

URL

PMID:29913388

[本文引用: 2]

In this study, we use separate eye-tracking measurements and functional magnetic resonance imaging to investigate the neuronal and behavioral response to painted portraits with direct versus averted gaze. We further explored modulatory effects of several painting characteristics (premodern vs modern period, influence of style and pictorial context). In the fMRI experiment, we show that the direct versus averted gaze elicited increased activation in lingual and inferior occipital and the fusiform face area, as well as in several areas involved in attentional and social cognitive processes, especially the theory of mind: angular gyrus/temporo-parietal junction, inferior frontal gyrus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. The additional eye-tracking experiment showed that participants spent more time viewing the portrait's eyes and mouth when the portrait's gaze was directed towards the observer. These results suggest that static and, in some cases, highly stylized depictions of human beings in artistic portraits elicit brain activation commensurate with the experience of being observed by a watchful intelligent being. They thus involve observers in implicit inferences of the painted subject's mental states and emotions. We further confirm the substantial influence of representational medium on brain activity.

Gaze and eye contact: A research review

Defining and quantifying the social phenotype in autism

Facial attractiveness biases the perception of eye contact

DOI:10.1080/17470218.2011.587254

URL

PMID:21756185

[本文引用: 1]

Attractive faces are appealing: We like to look at them, and we like to be looked at by them. We presented attractive and unattractive smiling and neutral faces containing identical eye regions with different gaze directions. Participants judged whether or not a face looked directly at them. Overall, attractive faces increased participants' tendency to perceive eye contact, consistent with a self-referential positivity bias. However, attractiveness effects were modulated by facial expression and gender: For female faces, observers more likely perceived eye contact in attractive than unattractive faces, independent of expression. For male faces, attractiveness effects were limited to neutral expressions and were absent in smiling faces. A signal detection analysis elucidated a systematic pattern in which (a) smiling faces, but not highly attractive faces, reduced sensitivity in gaze perception overall, and (b) attractiveness had a more consistent impact on bias than sensitivity measures. We conclude that combined influences of attractiveness, expression, and gender determine the formation of an overall impression when deciding which individual's interest in oneself may be beneficial and should be reciprocated.

The effect of head turn on the perception of gaze

DOI:10.1016/j.visres.2009.05.013

URL

PMID:19467254

[本文引用: 1]

When subjects viewed straight and turned eyes that were isolated singly or in pairs from a head that was straight or turned, they underestimated their true direction of gaze. They also underestimated the direction of head turn when both eyes were closed. However, the judged direction of gaze was improved when the eyes were layered against the heads. Judged direction of averted gaze was primarily based on the abducting eye. The effect that the deviation between an eye's optical axis and its true direction of gaze (angle kappa) has on its judged direction of gaze is discussed.

Unique morphology of the human eye

Unique morphology of the human eye and its adaptive meaning: Comparative studies on external morphology of the primate eye

DOI:10.1006/jhev.2001.0468

URL

PMID:11322803

[本文引用: 1]

In order to clarify the morphological uniqueness of the human eye and to obtain cues to understanding its adaptive significance, we compared the external morphology of the primate eye by measuring nearly half of all extant primate species. The results clearly showed exceptional features of the human eye: (1) the exposed white sclera is void of any pigmentation, (2) humans possess the largest ratio of exposed sclera in the eye outline, and (3) the eye outline is extraordinarily elongated in the horizontal direction. The close correlation of the parameters reflecting (2) and (3) with habitat type or body size of the species examined suggested that these two features are adaptations for extending the visual field by eyeball movement, especially in the horizontal direction. Comparison of eye coloration and facial coloration around the eye suggested that the dark coloration of exposed sclera of nonhuman primates is an adaptation to camouflage the gaze direction against other individuals and/or predators, and that the white sclera of the human eye is an adaptation to enhance the gaze signal. The uniqueness of human eye morphology among primates illustrates the remarkable difference between human and other primates in the ability to communicate using gaze signals.

Brain activation during eye gaze discrimination in stable schizophrenia

Getting to the bottom of face processing. Species-specific inversion effects for faces and behinds in humans and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0165357

URL

PMID:27902685

[本文引用: 1]

For social species such as primates, the recognition of conspecifics is crucial for their survival. As demonstrated by the 'face inversion effect', humans are experts in recognizing faces and unlike objects, recognize their identity by processing it configurally. The human face, with its distinct features such as eye-whites, eyebrows, red lips and cheeks signals emotions, intentions, health and sexual attraction and, as we will show here, shares important features with the primate behind. Chimpanzee females show a swelling and reddening of the anogenital region around the time of ovulation. This provides an important socio-sexual signal for group members, who can identify individuals by their behinds. We hypothesized that chimpanzees process behinds configurally in a way humans process faces. In four different delayed matching-to-sample tasks with upright and inverted body parts, we show that humans demonstrate a face, but not a behind inversion effect and that chimpanzees show a behind, but no clear face inversion effect. The findings suggest an evolutionary shift in socio-sexual signalling function from behinds to faces, two hairless, symmetrical and attractive body parts, which might have attuned the human brain to process faces, and the human face to become more behind-like.

Duration matters: Dissociating neural correlates of detection and evaluation of social gaze

DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.037

URL

PMID:19328236

[本文引用: 1]

The interpretation of interpersonal gaze behavior requires the use of complex cognitive processes and guides social interactions. Among a variety of different gaze characteristics, gaze direction and gaze duration modulate crucially the meaning of the

Attention orienting by another's gaze direction in children with autism

Maxims or myths of beauty? A meta-analytic and theoretical review

DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.390

URL

PMID:10825783

[本文引用: 1]

Common maxims about beauty suggest that attractiveness is not important in life. In contrast, both fitness-related evolutionary theory and socialization theory suggest that attractiveness influences development and interaction. In 11 meta-analyses, the authors evaluate these contradictory claims, demonstrating that (a) raters agree about who is and is not attractive, both within and across cultures; (b) attractive children and adults are judged more positively than unattractive children and adults, even by those who know them; (c) attractive children and adults are treated more positively than unattractive children and adults, even by those who know them; and (d) attractive children and adults exhibit more positive behaviors and traits than unattractive children and adults. Results are used to evaluate social and fitness-related evolutionary theories and the veracity of maxims about beauty.

The mutual influence of gaze and head orientation in the analysis of social attention direction

The influence of head contour and nose angle on the perception of eye-gaze direction

DOI:10.3758/bf03194970

URL

PMID:15495901

[本文引用: 2]

We report seven experiments that investigate the influence that head orientation exerts on the perception of eye-gaze direction. In each of these experiments, participants were asked to decide whether the eyes in a brief and masked presentation were looking directly at them or were averted. In each case, the eyes could be presented alone, or in the context of congruent or incongruent stimuli In Experiment 1A, the congruent and incongruent stimuli were provided by the orientation of face features and head outline. Discrimination of gaze direction was found to be better when face and gaze were congruent than in both of the other conditions, an effect that was not eliminated by inversion of the stimuli (Experiment 1B). In Experiment 2A, the internal face features were removed, but the outline of the head profile was found to produce an identical pattern of effects on gaze discrimination, effects that were again insensitive to inversion (Experiment 2B) and which persisted when lateral displacement of the eyes was controlled (Experiment 2C). Finally, in Experiment 3A, nose angle was also found to influence participants' ability to discriminate direct gaze from averted gaze, but here the effect was eliminated by inversion of the stimuli (Experiment 3B). We concluded that an image-based mechanism is responsible for the influence of head profile on gaze perception, whereas the analysis of nose angle involves the configural processing of face features.

Eye-direction detection: A dissociation between geometric and joint attention skills in autism

Targets and cues: Gaze-following in children with autism

Emotional expression affects the accuracy of gaze perception

The world smiles at me: Self-referential positivity bias when interpreting direction of attention

DOI:10.1080/02699931003794557

URL

PMID:21432675

[本文引用: 1]

Recent research suggests that eye-gaze direction modulates perceived emotional expression. Here we explore the extent to which emotion affects interpretation of attention direction. We captured three-dimensional face models of 8 actors expressing happy, fearful, angry and neutral emotions. From these 3D models 9 views were extracted (0 degrees , 2 degrees , 4 degrees , 6 degrees , 8 degrees to the left and right). These stimuli were randomly presented for 150 ms. Using a forced-choice paradigm 28 participants judged for each face whether or not it was attending to them. Two conditions were tested: either the whole face was visible, or the eyes were covered. In both conditions happy faces elicited most

Emotional expression modulates perceived gaze direction

DOI:10.1037/1528-3542.8.4.573

URL

PMID:18729587

[本文引用: 2]

Gaze perception is an important social skill, as it portrays information about what another person is attending to. Gaze direction has been shown to affect interpretation of emotional expression. Here the authors investigate whether the emotional facial expression has a reciprocal influence on interpretation of gaze direction. In a forced-choice yes-no task, participants were asked to judge whether three faces expressing different emotions (anger, fear, happiness, and neutral) in different viewing angles were looking at them or not. Happy faces were more likely to be judged as looking at the observer than were angry, fearful, or neutral faces. Angry faces were more often judged as looking at the observer than were fearful and neutral expressions. These findings are discussed on the background of approach and avoidance orientation of emotions and of the self-referential positivity bias.

Are you looking my way? Ostracism widens the cone of gaze

The effect of face orientation upon apparent direction of gaze

Illusory face dislocation effect and configurational integration in the inverted face

Perception of where a person is looking: Overestimation and underestimation of gaze direction

Individual differences in autistic traits predict the perception of direct gaze for males, but not for females

The effect of head orientation on perceived gaze direction: Revisiting Gibson and Pick (1963) and Cline (1967)

DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01191

URL

PMID:27559325

[本文引用: 3]

Two biases in perceived gaze direction have been observed when eye and head orientation are not aligned. An overshoot effect indicates that perceived gaze direction is shifted away from head orientation (i.e., a repulsive effect), whereas a towing effect indicates that perceived gaze direction falls in between head and eye orientation (i.e., an attraction effect). In the 60s, three influential papers have been published with respect to the effect of head orientation on perceived gaze direction (Gibson and Pick, 1963; Cline, 1967; Anstis et al., 1969). Throughout the years, the results of two of these (Gibson and Pick, 1963; Cline, 1967) have been interpreted differently by a number of authors. In this paper, we critically discuss potential sources of confusion that have led to differential interpretations of both studies. At first sight, the results of Cline (1967), despite having been a major topic of discussion, unambiguously seem to indicate a towing effect whereas Gibson and Pick's (1963) results seem to be the most ambiguous, although they have never been questioned in the literature. To shed further light on this apparent inconsistency, we repeated the critical experiments reported in both studies. Our results indicate an overshoot effect in both studies.

Gaze avoidance in social phobia: Objective measure and correlates

The dual nature of eye contact: To see and to be seen

DOI:10.1093/scan/nsv075

URL

PMID:26060324

[本文引用: 2]

Previous research has shown that physiological arousal and attentional responses to eye contact are modulated by one's knowledge of whether they are seen by another person. Recently it was shown that this 'eye contact effect' can be elicited without seeing another person's eyes at all. We aimed to investigate whether the eye contact effect is actually triggered by the mere knowledge of being seen by another individual, i.e. even in a condition when the perceiver does not see the other person at all. We measured experienced self-awareness and both autonomic and brain activity responses while participants were facing another person (a model) sitting behind a window. We manipulated the visibility of the model and the participants' belief of whether or not the model could see them. When participants did not see the model but believed they were seen by the model, physiological responses were attenuated in comparison to when both parties saw each other. However, self-assessed public self-awareness was not attenuated in this condition. Thus, two requirements must be met for physiological responses to occur in response to eye contact: an experience of being seen by another individual and an experience of seeing the other individual.

The effects of visible eye and head turn on the perception of being looked at

Take a look at the bright side: Effects of contrast polarity on gaze direction judgments

Autistic adults show preserved normalisation of sensory responses in gaze processing

DOI:10.1016/j.cortex.2018.02.005

URL

PMID:29549871

[本文引用: 1]

Progress in our understanding of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has recently been sought by characterising how systematic differences in canonical neural computations employed across the sensory cortex might contribute to clinical symptoms in diverse sensory, cognitive, and social domains. A key proposal is that ASD is characterised by reduced divisive normalisation of sensory responses. This provides a bridge between genetic and molecular evidence for an increased ratio of cortical excitation to inhibition in ASD and the functional characteristics of sensory coding that are relevant for understanding perception and behaviour. Here we tested this hypothesis in the context of gaze processing (i.e., the perception of other people's direction of gaze), a domain with direct relevance to the core diagnostic features of ASD. We show that reduced divisive normalisation in gaze processing is associated with specific predictions regarding the psychophysical effects of sensory adaptation to gaze direction, and test these predictions in adults with ASD. We report compelling evidence that both divisive normalisation and sensory adaptation occur robustly in adults with ASD in the context of gaze processing. These results have important theoretical implications for defining the types of divisive computations that are likely to be intact or compromised in this condition (e.g., relating to local vs distal control of cortical gain). These results are also a strong testament to the typical sensory coding of gaze direction in ASD, despite the atypical responses to others' gaze that are a hallmark feature of this diagnosis.

Reduced eye-gaze aftereffects in autism: Further evidence of diminished adaptation

DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.03.021

URL

PMID:23583965

[本文引用: 1]

Perceptual mechanisms are generally flexible or

Grasping the intentions of others: The perceived intentionality of an action influences activity in the superior temporal sulcus during social perception

DOI:10.1162/0898929042947900

URL

PMID:15701223

[本文引用: 1]

An explication of the neural substrates for social perception is an important component in the emerging field of social cognitive neuroscience and is relevant to the field of cognitive neuroscience as a whole. Prior studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that passive viewing of biological motion (Pelphrey, Mitchell, et al., 2003; Puce et al., 1998) activates the posterior superior temporal sulcus (STS ) region. Furthermore, recent evidence has shown that the perceived context of observed gaze shifts (Pelphrey, Singerman, et al., 2003; Pelphrey et al., 2004) modulates STS activity. Here, using event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging at 4 T, we investigated brain activity in response to passive viewing of goal- and nongoal-directed reaching-to-grasp movements. Participants viewed an animated character making reaching-to-grasp movements either toward (correct) or away (incorrect) from a blinking dial. Both conditions evoked significant posterior STS activity that was strongly right lateralized. By examining the time course of the blood oxygenation level-dependent response from areas of activation, we observed a functional dissociation. Incorrect trials evoked significantly greater activity in the STS than did correct trials, while an area posterior and inferior to the STS (likely corresponding to the MT/ V5 complex) responded equally to correct and incorrect movements. Parietal cortical regions, including the superior parietal lobule and the anterior intraparietal sulcus, also responded equally to correct and incorrect movements, but showed evidence for differential responding based on the hand and arm (left or right) of the animated character used to make the reaching-to-grasp movement. The results of this study further suggest that a region of the right posterior STS is involved in analyzing the intentions of other people's actions and that activity in this region is sensitive to the context of observed biological motions.

Neural basis of eye gaze processing deficits in autism

Visual scanning of faces in autism

DOI:10.1023/a:1016374617369

URL

PMID:12199131

[本文引用: 1]

The visual scanpaths of five high-functioning adult autistic males and five adult male controls were recorded using an infrared corneal reflection technique as they viewed photographs of human faces. Analyses of the scanpath data revealed marked differences in the scanpaths of the two groups. The autistic participants viewed nonfeature areas of the faces significantly more often and core feature areas of the faces (i.e., eyes, nose, and mouth) significantly less often than did control participants. Across both groups of participants, scanpaths generally did not differ as a function of the instructions given to the participants (i.e.,

Organization and functions of cells responsive to faces in the temporal cortex

DOI:10.1098/rstb.1992.0003

URL

PMID:1348133

[本文引用: 1]

Cells selectively responsive to the face have been found in several visual sub-areas of temporal cortex in the macaque brain. These include the lateral and ventral surfaces of inferior temporal cortex and the upper bank, lower bank and fundus of the superior temporal sulcus (STS). Cells in the different regions may contribute in different ways to the processing of the facial image. Within the upper bank of the STS different populations of cells are selective for different views of the face and head. These cells occur in functionally discrete patches (3-5 mm across) within the STS cortex. Studies of output connections from the STS also reveal a modular anatomical organization of repeating 3-5 mm patches connected to the parietal cortex, an area thought to be involved in spatial awareness and in the control of attention. The properties of some cells suggest a role in the discrimination of heads from other objects, and in the recognition of familiar individuals. The selectivity for view suggests that the neural operations underlying face or head recognition rely on parallel analyses of different characteristic views of the head, the outputs of these view-specific analyses being subsequently combined to support view-independent (object-centred) recognition. An alternative functional interpretation of the sensitivity to head view is that the cells enable an analysis of 'social attention', i.e. they signal where other individuals are directing their attention. A cell maximally responsive to the left profile thus provides a signal that the attention (of another individual) is directed to the observer's left. Such information is useful for analysing social interactions between other individuals.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Abnormal visual scan paths: A psychophysiological marker of delusions in schizophrenia

Does it make a difference if I have an eye contact with you or with your picture? An ERP study

DOI:10.1093/scan/nsq068

URL

PMID:20650942

[本文引用: 2]

Several recent studies have begun to examine the neurocognitive mechanisms involved in perceiving and responding to eye contact, a salient social signal of interest and readiness for interaction. Laboratory experiments measuring observers' responses to pictorial instead of live eye gaze cues may, however, only vaguely approximate the real-life affective significance of gaze direction cues. To take this into account, we measured event-related brain potentials and subjective affective responses in healthy adults while viewing live faces with a neutral expression through an electronic shutter and faces as pictures on a computer screen. Direct gaze elicited greater face-sensitive N170 amplitudes and early posterior negativity potentials than averted gaze or closed eyes, but only in the live condition. The results show that early-stage processing of facial information is enhanced by another person's direct gaze when the person is faced live. We propose that seeing a live face with a direct gaze is processed more intensely than a face with averted gaze or closed eyes, as the direct gaze is capable of intensifying the feeling of being the target of the other's interest and intentions. These results may have implications for the use of pictorial stimuli in the social cognition studies.

The observer observed: Frontal EEG asymmetry and autonomic responses differentiate between another person's direct and averted gaze when the face is seen live

Do faces capture the attention of individuals with Williams syndrome or autism? Evidence from tracking eye movements

DOI:10.1007/s10803-008-0641-z

URL

PMID:18787936

[本文引用: 1]

The neuro-developmental disorders of Williams syndrome (WS) and autism can reveal key components of social cognition. Eye-tracking techniques were applied in two tasks exploring attention to pictures containing faces. Images were (i) scrambled pictures containing faces or (ii) pictures of scenes with embedded faces. Compared to individuals who were developing typically, participants with WS and autism showed atypicalities of gaze behaviour. Individuals with WS showed prolonged face gaze across tasks, relating to the typical WS social phenotype. Participants with autism exhibited reduced face gaze, linking to a lack of interest in socially relevant information. The findings are interpreted in terms of wider issues regarding socio-cognition and attention mechanisms.

The positive and negative of human expertise in gaze perception

DOI:10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00092-5

URL

PMID:10980254

[本文引用: 2]

Judging where others look is crucial for many social and cognitive functions. Past accounts of gaze perception emphasize geometrical cues from the seen eye. Human eyes have a unique morphology, with a large white surround (sclera) to the dark iris that may have evolved to enhance gaze processing. Here we show that the contrast polarity of seen eyes has a powerful influence on gaze perception. Adult observers are highly inaccurate in judging gaze direction for images of human eyes with negative contrast polarity (regardless of whether the surrounding face is positive or negative), even though negative images of eyes preserve the geometric properties of positives that are judged accurately. The detrimental effect of negative contrast polarity is much larger for gaze perception than for other directional judgements (e.g. judging which way a head is turned). These results suggest an 'expert' system for gaze perception, which always treats the darker region of a seen eye as the part that does the looking.

Stress increases the feeling of being looked at

DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.06.013

URL

PMID:21767917

[本文引用: 1]

Eye gaze direction and facial expression are important social cues. Recent studies have shown that emotional expression affects interpretation of gaze direction in such a way that positive emotions are more favorably interpreted as making eye contact than negative or neutral expressions. Here we examine whether stress affects this positivity bias in gaze perception. Stress was induced in 25 healthy young adults by means of the cold pressure stress test (CPS), 24 participants serving as controls. Stimuli were created from three-dimensional face models of 8 actors expressing happy, fearful, angry and neutral emotions. From each of these 3D models we extracted 9 different views (0 degrees , 2 degrees , 4 degrees , 6 degrees and 8 degrees to the left and to the right). This resulted in 288 stimuli, which were randomly presented for 700 ms. Using a forced choice paradigm participants judged whether or not each face was looking at them. The results show that the CPS group falsely interpreted faces with averted gaze direction as making eye contact more often than did controls, independent of the expressed emotion. These results suggest that a stress-induced raise in cortisol level increases the sense of being looked at.

Are eyes special? It depends on how you look at it

Gaze discrimination in patients with schizophrenia: preliminary report

Being with virtual others: Neural correlates of social interaction

DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.017

URL

PMID:16171833

[本文引用: 1]

To characterize the neural correlates of being personally involved in social interaction as opposed to being a passive observer of social interaction between others we performed an fMRI study in which participants were gazed at by virtual characters (ME) or observed them looking at someone else (OTHER). In dynamic animations virtual characters then showed socially relevant facial expressions as they would appear in greeting and approach situations (SOC) or arbitrary facial movements (ARB). Differential neural activity associated with ME>OTHER was located in anterior medial prefrontal cortex in contrast to the precuneus for OTHER>ME. Perception of socially relevant facial expressions (SOC>ARB) led to differentially increased neural activity in ventral medial prefrontal cortex. Perception of arbitrary facial movements (ARB>SOC) differentially activated the middle temporal gyrus. The results, thus, show that activation of medial prefrontal cortex underlies both the perception of social communication indicated by facial expressions and the feeling of personal involvement indicated by eye gaze. Our data also demonstrate that distinct regions of medial prefrontal cortex contribute differentially to social cognition: whereas the ventral medial prefrontal cortex is recruited during the analysis of social content as accessible in interactionally relevant mimic gestures, differential activation of a more dorsal part of medial prefrontal cortex subserves the detection of self-relevance and may thus establish an intersubjective context in which communicative signals are evaluated.

All eyes on me?! Social anxiety and self-directed perception of eye gaze

DOI:10.1080/02699931.2013.773881

URL

PMID:23438447

[本文引用: 2]

To date, only little is known about the self-directed perception and processing of subtle gaze cues in social anxiety that might however contribute to excessive feelings of being looked at by others. Using a web-based approach, participants (n=174) were asked whether or not briefly (300 ms) presented facial expressions modulated in gaze direction (0 degrees , 2 degrees , 4 degrees , 6 degrees , 8 degrees ) and valence (angry, fearful, happy, neutral) were directed at them. The results demonstrate a positive, linear relationship between self-reported social anxiety and stronger self-directed perception of others' gaze directions, particularly for negative (angry, fearful) and neutral expressions. Furthermore, faster responding was found for gaze more clearly directed at socially anxious individuals (0 degrees , 2 degrees , and 4 degrees ) suggesting a tendency to avoid direct gaze. In sum, the results illustrate an altered self-directed perception of subtle gaze cues. The possibly amplifying effects of social stress on biased self-directed perception of eye gaze are discussed.

Direct gaze captures visuospatial attention

Does perceived direct gaze boost detection in adults and children with and without autism? The stare-in-the-crowd effect revisited

Is anyone looking at me? Direct gaze detection in children with and without autism

DOI:10.1016/j.bandc.2007.12.001

URL

PMID:18226847

[本文引用: 3]

Atypical processing of eye contact is one of the significant characteristics of individuals with autism, but the mechanism underlying atypical direct gaze processing is still unclear. This study used a visual search paradigm to examine whether the facial context would affect direct gaze detection in children with autism. Participants were asked to detect target gazes presented among distracters with different gaze directions. The target gazes were either direct gaze or averted gaze, which were either presented alone (Experiment 1) or within facial context (Experiment 2). As with the typically developing children, the children with autism, were faster and more efficient to detect direct gaze than averted gaze, whether or not the eyes were presented alone or within faces. In addition, face inversion distorted efficient direct gaze detection in typically developing children, but not in children with autism. These results suggest that children with autism use featural information to detect direct gaze, whereas typically developing children use configural information to detect direct gaze.

Reflexive orienting in response to eye gaze and an arrow in children with and without autism

DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00236.x

URL

PMID:15055365

[本文引用: 1]

BACKGROUND: This study investigated whether another person's social attention, specifically the direction of their eye gaze, and a non-social directional cue, an arrow, triggered reflexive orienting in children with and without autism in an experimental situation. METHODS: Children with autism and typically developed children participated in one of two experiments. Both experiments involved the localization of a target that appeared to the left or right of the fixation point. Before the target appeared, the participant's attention was cued to the left or right by either an arrow or the direction of eye gaze on a computerized face. RESULTS: Children with autism were slower to respond, which suggests a slight difference in the general cognitive ability of the groups. In Experiment 1, although the participants were instructed to disregard the cue and the target was correctly cued in only 50% of the trials, both groups of children responded significantly faster to cued targets than to uncued targets, regardless of the cue. In Experiment 2, children were instructed to attend to the direction opposite that of the cues and the target was correctly cued in only 20% of the trials. Typically developed children located targets cued by eye gaze more quickly, while the arrow cue did not trigger such reflexive orienting in these children. However, both social and non-social cues shifted attention to the cued location in children with autism. CONCLUSION: These results indicate that eye gaze attracted attention more effectively than the arrow in typically developed children, while children with autism shifted their attention equally in response to eye gaze and arrow direction, failing to show preferential sensitivity to the social cue. Difficulty in shifting controlled attention to the instructed side was also found in children with autism.

The effect of torso direction on the judgement of eye direction

Intact unconscious processing of eye contact in schizophrenia

The effect of central vision loss on perception of mutual gaze

Does the perception of moving eyes trigger reflexive visual orienting in autism?

DOI:10.1098/rstb.2002.1203

URL

PMID:12639330

[本文引用: 1]

Does movement of the eyes in one or another direction function as an automatic attentional cue to a location of interest? Two experiments explored the directional movement of the eyes in a full face for speed of detection of an aftercoming location target in young people with autism and in control participants. Our aim was to investigate whether a low-level perceptual impairment underlies the delay in gaze following characteristic of autism. The participants' task was to detect a target appearing on the left or right of the screen either 100 ms or 800 ms after a face cue appeared with eyes averting to the left or right. Despite instructions to ignore eye-movement in the face cue, people with autism and control adolescents were quicker to detect targets that had been preceded by an eye movement cue congruent with target location compared with targets preceded by an incongruent eye movement cue. The attention shifts are thought to be reflexive because the cue was to be ignored, and because the effect was found even when cue-target duration was short (100 ms). Because (experiment two) the effect persisted even when the face was inverted, it would seem that the direction of movement of eyes can provide a powerful (involuntary) cue to a location.

What are you looking at? Acuity for triadic eye gaze

The authors measured observers' ability to determine direction of gaze toward an object in space. In Experiment 1, they determined the difference threshold for determining whether a live

Social cognition modulates the sensory coding of observed gaze direction

DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.069

URL

PMID:19559619

[本文引用: 1]

Gaze direction is an important social signal in both human and nonhuman primates, providing information about conspecifics' attention, interests, and intentions. Single-unit recordings in macaques have revealed neurons selective for others' specific gaze direction. A parallel functional organization in the human brain is indicated by gaze-adaptation experiments, in which systematic distortions in gaze perception following prolonged exposure to static face images reveal dynamic interactions in local cortical circuitry. However, our understanding of the influence of high-level social cognition on these processes in monkeys and humans is still rudimentary. Here we show that the attribution of a mental state to another person determines the way in which the human brain codes observed gaze direction. Specifically, we convinced observers that prerecorded video sequences of an experimenter gazing left or right were a live video link to an adjacent room. The experimenter wore mirrored goggles that observers believed were either transparent such that the person could see, or opaque such that the person could not see. The effects of adaptation were enhanced under the former condition relative to the latter, indicating that high-level sociocognitive processes shape and modulate sensory coding of observed gaze direction.

Geometrical basis of perception of gaze direction

DOI:10.1016/j.visres.2006.04.011

URL

PMID:16904157

[本文引用: 2]