CN 11-4766/R

主办:中国科学院心理研究所

出版:科学出版社

Advances in Psychological Science ›› 2024, Vol. 32 ›› Issue (2): 364-385.doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2024.00364

• Regular Articles • Previous Articles Next Articles

Received:2023-03-29

Online:2024-02-15

Published:2023-11-23

Contact:

WANG Zhen

E-mail:wangzhen@smhc.org.cn

CLC Number:

WU Chaoyi, WANG Zhen. The dynamic features of emotion dysregulation in major depressive disorder: An emotion dynamics perspective[J]. Advances in Psychological Science, 2024, 32(2): 364-385.

| 情绪动态特征 | 定义 | 数学表达式/统计模型参数 | 时间 依赖性 | 参考文献 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 情绪均值 (Mean) | 个体在一段时间内情绪的平均强度 | 个体内水平所有情绪观测值的均值。 | 无 | Clark & Tellegen, |

| 2. 情绪变异性 (Variability) | 个体在一段时间内情绪体验的整体变化幅度 | 一段时间内所有情绪观测值的个体内标准差。 | 无 | (Jahng et al., |

| 3. 情绪不稳定性 (Instability) | 个体在连续2个时间点之间的情绪波动幅度或情绪剧变概率 | MSSD: 连续2个时间点的情绪观测值Xi和Xi+1的平方差的均值(部分研究采用RMSSD, 即将MSSD开平方根)。 | 有 | (Jahng et al., |

| AC)的概率。AC通常设定为样本第90百分位数等。 | ||||

| 4. 相对变异指数 (Relative Variability Index) | 控制和修正变异性、不稳定性指标和均值之间的统计依赖关系 | 将原来的变异性、不稳定性统计量Vi除以个体i 给定均值Mi后的最大可能的变异性max (Vi | Mi)。修正后的指标常用SD*、MSSD*表示。 | SD*无 MSSD* 有 | (Mestdagh et al., |

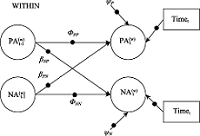

| 5. 情绪惯性 (Inertia) | 个体当前的情绪状态多大程度上可以被之前的情绪状态所预测 | 多水平模型中情绪的自回归系数。例如, 消极情绪惯性是个体内水平t−1时间测的NA (w) t−1预测t时间测的NA (w)t的回归系数ΦNN。 | 有 | (Hamaker et al., |

| 6. 情绪反应性 (Reactivity) | 个体响应外部事件所产生的情绪变化 | 多水平模型中上个时间点的情绪事件预测当下情绪的回归系数。对消极事件的消极情绪反应性为个体内水平t时间测的上个时间点的NE (w)t (条目描述是“从上次测量到现在的情绪事件”, 条目本身具有时间滞后性)预测t时间测的当下的NA (w)t的回归系数βNE。 | 有 | (Booij et al., |

| 7. 情绪网络密度 (Network Density) | 个体当下的特定情绪如何受上个时间点各种情绪的影响 | 通过网络分析建立一系列多水平VAR模型, 模型中t时间的特定情绪被t−1时间点的所有情绪(包括特定情绪自身)所预测。计算该个体所有回归系数的绝对值的均值。 | 有 | (Bringmann et al., |

| 8. 情绪分化 (Differentiation) | 个体区别多种离散情绪的能力 | 通过ICC计算相同效价下多种情绪之间的组内相关系数, ICC越小代表情绪分化水平越高。 | 无 | Liu, et al., |

| 情绪动态特征 | 定义 | 数学表达式/统计模型参数 | 时间 依赖性 | 参考文献 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 情绪均值 (Mean) | 个体在一段时间内情绪的平均强度 | 个体内水平所有情绪观测值的均值。 | 无 | Clark & Tellegen, |

| 2. 情绪变异性 (Variability) | 个体在一段时间内情绪体验的整体变化幅度 | 一段时间内所有情绪观测值的个体内标准差。 | 无 | (Jahng et al., |

| 3. 情绪不稳定性 (Instability) | 个体在连续2个时间点之间的情绪波动幅度或情绪剧变概率 | MSSD: 连续2个时间点的情绪观测值Xi和Xi+1的平方差的均值(部分研究采用RMSSD, 即将MSSD开平方根)。 | 有 | (Jahng et al., |

| AC)的概率。AC通常设定为样本第90百分位数等。 | ||||

| 4. 相对变异指数 (Relative Variability Index) | 控制和修正变异性、不稳定性指标和均值之间的统计依赖关系 | 将原来的变异性、不稳定性统计量Vi除以个体i 给定均值Mi后的最大可能的变异性max (Vi | Mi)。修正后的指标常用SD*、MSSD*表示。 | SD*无 MSSD* 有 | (Mestdagh et al., |

| 5. 情绪惯性 (Inertia) | 个体当前的情绪状态多大程度上可以被之前的情绪状态所预测 | 多水平模型中情绪的自回归系数。例如, 消极情绪惯性是个体内水平t−1时间测的NA (w) t−1预测t时间测的NA (w)t的回归系数ΦNN。 | 有 | (Hamaker et al., |

| 6. 情绪反应性 (Reactivity) | 个体响应外部事件所产生的情绪变化 | 多水平模型中上个时间点的情绪事件预测当下情绪的回归系数。对消极事件的消极情绪反应性为个体内水平t时间测的上个时间点的NE (w)t (条目描述是“从上次测量到现在的情绪事件”, 条目本身具有时间滞后性)预测t时间测的当下的NA (w)t的回归系数βNE。 | 有 | (Booij et al., |

| 7. 情绪网络密度 (Network Density) | 个体当下的特定情绪如何受上个时间点各种情绪的影响 | 通过网络分析建立一系列多水平VAR模型, 模型中t时间的特定情绪被t−1时间点的所有情绪(包括特定情绪自身)所预测。计算该个体所有回归系数的绝对值的均值。 | 有 | (Bringmann et al., |

| 8. 情绪分化 (Differentiation) | 个体区别多种离散情绪的能力 | 通过ICC计算相同效价下多种情绪之间的组内相关系数, ICC越小代表情绪分化水平越高。 | 无 | Liu, et al., |

| N | 抑郁组 | 对照组 | EMA | 情绪条目 | 与抑郁症情绪动态特征相关的研究结果 | 文献 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 伴快感缺失MDD患者(47) | 健康对照 (40) | 10×7 | PA: euphoric, happy, relaxed | 与健康对照组相比, 伴有快感缺失的MDD患者PA均值更小, 但PA变异性、PA不稳定性、PA惯性、PA反应性没有显著差异。 | (Heininga et al., |

| 2 | 1. MDD/AD患者(95) 2. MDD/AD缓解期个体(178) | 健康对照 (92) | 5×14 | PA: satisfied, relaxed, cheerful, energetic, enthusiastic, calm NA: upset, irritated, listless, down, nervous, bored, anxious | 1. MDD/AD患者PA和NA的不稳定性(RMSSD)和变异性, 以及NA均值和惯性最大, 其次是缓解期个体, 最后是健康对照组。 2. MDD/AD患者PA均值最小, 其次是缓解期个体, 健康对照组PA均值最大。 3. MDD/AD患者和缓解期个体的PA情绪惯性没有显著差异, 都大于健康对照组。 4.采用RMSSD*控制情绪均值的效应后, 三个组别的情绪不稳定性的组间差异仍显著, 但MDD/AD患者和缓解期个体之间的差异不再显著。 | (Schoevers et al., |

| 3 | 1. MDD患者(26) 2. MDD缓解期个体(82) | 健康对照 (471) | 10×5 | PA: cheerful, content, energetic, enthusiastic NA: insecure, lonely, anxious, low, guilty, suspicious | 1.与健康对照组相比, MDD患者过夜的NA惯性更大。 2.与健康对照组相比, 缓解期的个体日间的NA惯性更大。 3.过夜的NA惯性与睡眠时长和质量的关系在不同组别存在差异。 | (Minaeva et al., |

| 4 | MDD患者 (53) | 健康对照 (53) | 8×7 | PA: happy, excited, alert, active NA: sad, anxious, angry, frustrated, ashamed, disgusted, guilty | MDD患者整体的情绪网络更密集, 并且这种差异源于NA网络密度而非PA网络密度的差异。 | (Pe et al., |

| 5 | 1. MDD患者(48) 2. MDD缓解期个体(80) | 健康对照 (87) | 5×14 | PA: relaxed, content, calm, happy, excited, enthusiastic NA: bored, sluggish, sad, frustrated, nervous, angry | 1. MDD患者的NA均值大于处于缓解期的个体, 处于缓解期的个体的NA均值大于健康对照组。 2. MDD患者的PA均值小于处于缓解期的个体和健康对照组, 处于缓解期的个体和健康对照组的PA均值没有显著差异。 3. 与健康对照组相比, MDD患者和处于缓解期的个体NA和PA的情绪分化水平更低, MDD患者和缓解期个体的情绪分化水平没有显著差异。 | Liu, et al., |

| 6 | MDD患者 (40) | 健康对照 (40) | 10×4 | PA: joy, even temper, satisfaction NA: sadness, fear, anger, rage, guilt, shame, disgust | 1.与健康对照组相比, MDD患者NA均值更大, PA均值更小, NA惯性和NA变异性更大。 2.与健康对照组相比, MDD患者经历积极事件后表现出心境点亮效应(更大程度的NA减少)。 3.与健康对照组相比, MDD患者NA情绪不稳定性更大。但控制情绪变异性的效应后, 这两个组别的组间差异不显著。 | (J. Nelson et al., |

| 7 | 1. MDD患者(48) 2. MDD缓解期个体(80) | 健康对照 (87) | 5×14 | PA: relaxed, content, calm, happy, excited, enthusiastic NA: bored, sluggish, sad, frustrated, nervous, angry | 1. MDD患者的NA均值和NA变异性最大, 健康对照组最小, 处于缓解期的个体介于两者之间。控制NA均值后, NA变异性的组间差异仍显著。 2. 3个组别NA惯性的组间差异不显著。 3. 对于PA的情绪动力指标而言, 只有PA均值在3个组别的组间差异显著。抑郁症患者的PA均值小于处于缓解期的个体和健康对照组, 而处于缓解期的个体和健康对照组的PA均值没有显著差异。 | & English, |

| 8 | 具有MDD终身诊断的患者(116), 其中40.5%当前被诊断为MDD | 1. 健康对照(65) 2. 双相障碍I型(33) 3. 双相障碍II型(37) 4. 焦虑障碍(36) | 4×14 | 效价: very happy (1) to very sad (7) 唤醒程度: very calm (1) to very anxious (7) | 1.与健康对照组相比, 具有MDD终身诊断的患者悲伤、焦虑情绪的均值和焦虑情绪的变异性, 以及悲伤、焦虑情绪的不稳定性更大。 2.经历积极事件后, 具有MDD终身诊断的患者(相比健康对照组)表现出心境点亮效应(更大程度的焦虑情绪减少)。经历消极事件后, 具有MDD终身诊断的患者表现出更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的焦虑情绪增加)。 3.进一步将具有MDD终身诊断的患者细分为当下患有MDD的患者、处于缓解期的个体两个组别后, 两个组别的情绪反应性没有显著差异。 | (Lamers et al., |

| 9 | MDD患者且共病BPD (20) | MDD患者没有共病BPD (21) | 5×7 | PA: happy, content, relaxed NA: sad, anxious, angry, empty, lonely, guilty, tense | 1.共病BPD和不共病BPD的两组MDD患者在情绪不稳定性, 以及与他人积极互动/与他人消极互动/感知到被拒绝/感知到失败后的总体情绪反应性上没有组间差异。 2.相比于不共病BPD的MDD患者, 共病BPD的MDD患者在经历了独自一人的事件后体验到了更大的情绪反应性(更大程度的总体情绪恶化)。 | (Köhling et al., |

| 10 | 1. 患MDD的大一学生(23) 2. 缓解期的大一学生(42) | 无MDD病史的大一学生(43) | 4×14 | NA: sad, alone, angry with self, guilty, lonely, hopeless | 1. 相比于处于缓解期和无MDD病史的个体, MDD患者对于日常感知到的压力表现出更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的NA增加)。 2. MDD患者对人际消极事件表现出更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的NA增加), 而处于缓解期和无MDD病史的个体对人际或非人际的消极事件的情绪反应性没有显著差异。 | (Sheets & Armey, |

| 11 | MDD患者(30), 治疗后分为: 1.症状缓解组(11) 2.症状没有缓解组(19) | 健康对照 (39) | 10×6 | PA: energetic, enthusiastic, happy, cheerful, talkative, strong, satisfied, self-assured NA: anxious, irritated, restless, tense, guilty, edgy, distractible, agitated | 1.相比于健康对照组和缓解期组, 症状未缓解的MDD患者对事件、活动和社交这三种应激源的NA情绪反应性更大(更大程度的NA增加)。 2.缓解期组和健康对照组在对事件和活动应激源的情绪反应性上没有组间差异, 但是缓解期组(相对于健康对照组)仍表现出对社交应激源更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的NA增加)。 | (van Winkel et al., |

| 12 | MDD或GAD患者(61) | 健康对照(58) | 9×8 | PA: relaxed, content, excited, enthusiastic NA: angry, tired, irritable, anxious, depressed | 基于EMA得到的NA和PA的网络密度都在人口学特征和情绪均值、标准差之上显著预测个体的诊断状态。具体而言, 更大的NA情绪网络密度、更小的PA情绪网络密度与MDD/GAD的诊断存在相关。 | (Shin et al., |

| 13 | 处于复发性MDD缓解期的个体(51) | 健康对照(51) | 10×5 | PA: cheerful, energetic, enthusiastic, satisfied, relaxed, calm NA: upset, irritated, nervous, listless, down, bored | 1.处于复发性MDD缓解期的个体(相比于健康对照组)在经历消极日常事件后表现出更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的NA增加)。 2.处于复发性MDD缓解期的个体(相比于健康对照组)在经历积极日常事件后表现出心境点亮效应(更大程度的PA增加和更大程度的NA减少)。 | (Schricker et al., |

| 14 | 1.MDD不共病GAD (38) 2.MDD共病GAD (38) | 1.GAD, 且不共病MDD (36) 2.健康对照(33) | 8×7 | PA: happy, proud, determined NA: sad, anxious, dissatisfied with myself | 1.MDD不共病GAD组和MDD共病GAD组的患者(相比于健康对照组)在经历积极事件后都表现出心境点亮效应 (更大程度的PA增加和更大程度的NA减少)。 2.患者基线抑郁症状越严重, 心境点亮效应更强。 3.与GAD相比, MDD对积极事件的情绪反应性改变更具有特异性。 | (Khazanov et al., |

| 15 | MDD患者(31) | 健康对照 (33) | 10×6 | PA: happy, relaxed, interested, enjoying myself NA: irritated, down, anxious, tense, ashamed, guilty | 1. 相比于健康对照组, MDD患者表现出更大的NA和PA的情绪变异性和不稳定性。 2. MDD患者和健康对照组在日间积极情绪的时间趋势上存在差异, MDD患者每天积极情绪随时间的变化呈现为倒U型, 而健康对照组呈现为正向的线性趋势。 | (Crowe et al., |

| 16 | MDD患者(41) | 健康对照 (33) | 10×3 | DA: depressed, sad | 相比于健康对照组, MDD患者在经历日常积极事件后表现出心境点亮效应(更大程度的烦躁情绪减少)。 | (Panaite et al., |

| 17 | DD患者(38) | BPD患者(67) | 6×28 | NA: fear (6 items) hostility (6 items) sadness (5 items) 详见(Watson & Clark, | 1. DD患者NA情绪分化水平高于BPD患者。 2. NA情绪分化水平可以负向预测冲动性, 但预测的效应在DD患者和BPD患者两个组别中没有显著差异。 | (Tomko et al., |

| 18 | 有MDD既往诊断史, 且目前轻度抑郁的患者(129) | 1. 健康对照(207) 2. 精神病性障碍患者(263) | 10× (5/6) | PA: cheerful, content NA: insecure, down, suspicious | 1.相比于精神病性障碍组和健康对照组, 抑郁症患者的情绪状态网络的节点间的联系最为紧密。 2.相比于精神病性障碍组, 抑郁症患者的网络结构表现出更多的积极和消极心理状态之间的特异性联系。 | (Wigman et al., |

| N | 抑郁组 | 对照组 | EMA | 情绪条目 | 与抑郁症情绪动态特征相关的研究结果 | 文献 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 伴快感缺失MDD患者(47) | 健康对照 (40) | 10×7 | PA: euphoric, happy, relaxed | 与健康对照组相比, 伴有快感缺失的MDD患者PA均值更小, 但PA变异性、PA不稳定性、PA惯性、PA反应性没有显著差异。 | (Heininga et al., |

| 2 | 1. MDD/AD患者(95) 2. MDD/AD缓解期个体(178) | 健康对照 (92) | 5×14 | PA: satisfied, relaxed, cheerful, energetic, enthusiastic, calm NA: upset, irritated, listless, down, nervous, bored, anxious | 1. MDD/AD患者PA和NA的不稳定性(RMSSD)和变异性, 以及NA均值和惯性最大, 其次是缓解期个体, 最后是健康对照组。 2. MDD/AD患者PA均值最小, 其次是缓解期个体, 健康对照组PA均值最大。 3. MDD/AD患者和缓解期个体的PA情绪惯性没有显著差异, 都大于健康对照组。 4.采用RMSSD*控制情绪均值的效应后, 三个组别的情绪不稳定性的组间差异仍显著, 但MDD/AD患者和缓解期个体之间的差异不再显著。 | (Schoevers et al., |

| 3 | 1. MDD患者(26) 2. MDD缓解期个体(82) | 健康对照 (471) | 10×5 | PA: cheerful, content, energetic, enthusiastic NA: insecure, lonely, anxious, low, guilty, suspicious | 1.与健康对照组相比, MDD患者过夜的NA惯性更大。 2.与健康对照组相比, 缓解期的个体日间的NA惯性更大。 3.过夜的NA惯性与睡眠时长和质量的关系在不同组别存在差异。 | (Minaeva et al., |

| 4 | MDD患者 (53) | 健康对照 (53) | 8×7 | PA: happy, excited, alert, active NA: sad, anxious, angry, frustrated, ashamed, disgusted, guilty | MDD患者整体的情绪网络更密集, 并且这种差异源于NA网络密度而非PA网络密度的差异。 | (Pe et al., |

| 5 | 1. MDD患者(48) 2. MDD缓解期个体(80) | 健康对照 (87) | 5×14 | PA: relaxed, content, calm, happy, excited, enthusiastic NA: bored, sluggish, sad, frustrated, nervous, angry | 1. MDD患者的NA均值大于处于缓解期的个体, 处于缓解期的个体的NA均值大于健康对照组。 2. MDD患者的PA均值小于处于缓解期的个体和健康对照组, 处于缓解期的个体和健康对照组的PA均值没有显著差异。 3. 与健康对照组相比, MDD患者和处于缓解期的个体NA和PA的情绪分化水平更低, MDD患者和缓解期个体的情绪分化水平没有显著差异。 | Liu, et al., |

| 6 | MDD患者 (40) | 健康对照 (40) | 10×4 | PA: joy, even temper, satisfaction NA: sadness, fear, anger, rage, guilt, shame, disgust | 1.与健康对照组相比, MDD患者NA均值更大, PA均值更小, NA惯性和NA变异性更大。 2.与健康对照组相比, MDD患者经历积极事件后表现出心境点亮效应(更大程度的NA减少)。 3.与健康对照组相比, MDD患者NA情绪不稳定性更大。但控制情绪变异性的效应后, 这两个组别的组间差异不显著。 | (J. Nelson et al., |

| 7 | 1. MDD患者(48) 2. MDD缓解期个体(80) | 健康对照 (87) | 5×14 | PA: relaxed, content, calm, happy, excited, enthusiastic NA: bored, sluggish, sad, frustrated, nervous, angry | 1. MDD患者的NA均值和NA变异性最大, 健康对照组最小, 处于缓解期的个体介于两者之间。控制NA均值后, NA变异性的组间差异仍显著。 2. 3个组别NA惯性的组间差异不显著。 3. 对于PA的情绪动力指标而言, 只有PA均值在3个组别的组间差异显著。抑郁症患者的PA均值小于处于缓解期的个体和健康对照组, 而处于缓解期的个体和健康对照组的PA均值没有显著差异。 | & English, |

| 8 | 具有MDD终身诊断的患者(116), 其中40.5%当前被诊断为MDD | 1. 健康对照(65) 2. 双相障碍I型(33) 3. 双相障碍II型(37) 4. 焦虑障碍(36) | 4×14 | 效价: very happy (1) to very sad (7) 唤醒程度: very calm (1) to very anxious (7) | 1.与健康对照组相比, 具有MDD终身诊断的患者悲伤、焦虑情绪的均值和焦虑情绪的变异性, 以及悲伤、焦虑情绪的不稳定性更大。 2.经历积极事件后, 具有MDD终身诊断的患者(相比健康对照组)表现出心境点亮效应(更大程度的焦虑情绪减少)。经历消极事件后, 具有MDD终身诊断的患者表现出更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的焦虑情绪增加)。 3.进一步将具有MDD终身诊断的患者细分为当下患有MDD的患者、处于缓解期的个体两个组别后, 两个组别的情绪反应性没有显著差异。 | (Lamers et al., |

| 9 | MDD患者且共病BPD (20) | MDD患者没有共病BPD (21) | 5×7 | PA: happy, content, relaxed NA: sad, anxious, angry, empty, lonely, guilty, tense | 1.共病BPD和不共病BPD的两组MDD患者在情绪不稳定性, 以及与他人积极互动/与他人消极互动/感知到被拒绝/感知到失败后的总体情绪反应性上没有组间差异。 2.相比于不共病BPD的MDD患者, 共病BPD的MDD患者在经历了独自一人的事件后体验到了更大的情绪反应性(更大程度的总体情绪恶化)。 | (Köhling et al., |

| 10 | 1. 患MDD的大一学生(23) 2. 缓解期的大一学生(42) | 无MDD病史的大一学生(43) | 4×14 | NA: sad, alone, angry with self, guilty, lonely, hopeless | 1. 相比于处于缓解期和无MDD病史的个体, MDD患者对于日常感知到的压力表现出更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的NA增加)。 2. MDD患者对人际消极事件表现出更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的NA增加), 而处于缓解期和无MDD病史的个体对人际或非人际的消极事件的情绪反应性没有显著差异。 | (Sheets & Armey, |

| 11 | MDD患者(30), 治疗后分为: 1.症状缓解组(11) 2.症状没有缓解组(19) | 健康对照 (39) | 10×6 | PA: energetic, enthusiastic, happy, cheerful, talkative, strong, satisfied, self-assured NA: anxious, irritated, restless, tense, guilty, edgy, distractible, agitated | 1.相比于健康对照组和缓解期组, 症状未缓解的MDD患者对事件、活动和社交这三种应激源的NA情绪反应性更大(更大程度的NA增加)。 2.缓解期组和健康对照组在对事件和活动应激源的情绪反应性上没有组间差异, 但是缓解期组(相对于健康对照组)仍表现出对社交应激源更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的NA增加)。 | (van Winkel et al., |

| 12 | MDD或GAD患者(61) | 健康对照(58) | 9×8 | PA: relaxed, content, excited, enthusiastic NA: angry, tired, irritable, anxious, depressed | 基于EMA得到的NA和PA的网络密度都在人口学特征和情绪均值、标准差之上显著预测个体的诊断状态。具体而言, 更大的NA情绪网络密度、更小的PA情绪网络密度与MDD/GAD的诊断存在相关。 | (Shin et al., |

| 13 | 处于复发性MDD缓解期的个体(51) | 健康对照(51) | 10×5 | PA: cheerful, energetic, enthusiastic, satisfied, relaxed, calm NA: upset, irritated, nervous, listless, down, bored | 1.处于复发性MDD缓解期的个体(相比于健康对照组)在经历消极日常事件后表现出更大的NA情绪反应性(更大程度的NA增加)。 2.处于复发性MDD缓解期的个体(相比于健康对照组)在经历积极日常事件后表现出心境点亮效应(更大程度的PA增加和更大程度的NA减少)。 | (Schricker et al., |

| 14 | 1.MDD不共病GAD (38) 2.MDD共病GAD (38) | 1.GAD, 且不共病MDD (36) 2.健康对照(33) | 8×7 | PA: happy, proud, determined NA: sad, anxious, dissatisfied with myself | 1.MDD不共病GAD组和MDD共病GAD组的患者(相比于健康对照组)在经历积极事件后都表现出心境点亮效应 (更大程度的PA增加和更大程度的NA减少)。 2.患者基线抑郁症状越严重, 心境点亮效应更强。 3.与GAD相比, MDD对积极事件的情绪反应性改变更具有特异性。 | (Khazanov et al., |

| 15 | MDD患者(31) | 健康对照 (33) | 10×6 | PA: happy, relaxed, interested, enjoying myself NA: irritated, down, anxious, tense, ashamed, guilty | 1. 相比于健康对照组, MDD患者表现出更大的NA和PA的情绪变异性和不稳定性。 2. MDD患者和健康对照组在日间积极情绪的时间趋势上存在差异, MDD患者每天积极情绪随时间的变化呈现为倒U型, 而健康对照组呈现为正向的线性趋势。 | (Crowe et al., |

| 16 | MDD患者(41) | 健康对照 (33) | 10×3 | DA: depressed, sad | 相比于健康对照组, MDD患者在经历日常积极事件后表现出心境点亮效应(更大程度的烦躁情绪减少)。 | (Panaite et al., |

| 17 | DD患者(38) | BPD患者(67) | 6×28 | NA: fear (6 items) hostility (6 items) sadness (5 items) 详见(Watson & Clark, | 1. DD患者NA情绪分化水平高于BPD患者。 2. NA情绪分化水平可以负向预测冲动性, 但预测的效应在DD患者和BPD患者两个组别中没有显著差异。 | (Tomko et al., |

| 18 | 有MDD既往诊断史, 且目前轻度抑郁的患者(129) | 1. 健康对照(207) 2. 精神病性障碍患者(263) | 10× (5/6) | PA: cheerful, content NA: insecure, down, suspicious | 1.相比于精神病性障碍组和健康对照组, 抑郁症患者的情绪状态网络的节点间的联系最为紧密。 2.相比于精神病性障碍组, 抑郁症患者的网络结构表现出更多的积极和消极心理状态之间的特异性联系。 | (Wigman et al., |

| 序号 | 文献 | 依从性 | 信度 | 效度 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heininga et al., | 问卷填写依从率达到89%。 | PA的个体内Cronbach’s α = 0.03, 个体间Cronbach’s α = 0.99 | 效标效度: 文章中报告:与健康对照组相比, 伴有快感缺失的MDD患者PA均值更低。 |

| 2 | Schoevers et al., | 发给所有被试的所有问卷中, 仅8.72%缺失。93%的参与者填写率超过80%。 | 未报告 | 1) 效标效度: 文章中报告:当前患有MDD/AD患者NA均值最高, 其次是缓解期个体, 最后是健康对照组。PA则相反。该文献的附录提供了各情绪条目在3个组别中的均值。 2) 结构效度: 附录中提供了各情绪条目和PA、NA总分之间的相关系数。 |

| 3 | Minaeva et al., | 621个被试中, 有610个被试完成了EMA测量。 | 1) PA的个体内omega为0.79; 个体间omega为0.95。 2) NA的个体内omega为0.68; 个体间omega为0.91。 | 1) 效标效度: 正文表格1表明:MDD患者的NA中位数最大, 其次是缓解期个体, 最后是健康对照组。PA均值则相反。 2) 结构效度: 该研究选择过往研究在PA、NA潜因子上具有最高因子负荷和个体内变异性的条目。 |

| 4 | Pe et al., | 未报告 | 未报告 | 效标效度: 文章中报告:MDD患者的NA网络密度大于健康对照组。 |

| 5 | Thompson, Liu, et al., | 平均问卷完成率为74.8%, 标准差18.3%, 范围在20%到99%。 | 通过混合模型得到PA的Cronbach’s α为0.65, NA的Cronbach’s α为0.74。PA和NA具有足够的个体内变异性, PA的ICC为0.42, NA的ICC为0.43。 | 效标效度: 1) 文章中报告了健康对照组、处于抑郁症缓解期组和MDD患者组在NA和PA均值存在组间差异。 2) 正文 |

| 6 | J. Nelson et al., | 抑郁症组EMA问卷完成率为90%, 健康对照组完成率为87%。 | ICC的结果表明:对于PA, 71%的总方差是个体间方差, 29%的总方差是个体内方差。对于NA, 66%的总方差是个体间方差, 34%的总方差是个体内方差。 | 结构效度: 探索性因素分析的结果表明:情绪问卷是双因子结构, PA和NA分别是两个因子。 |

| 7 | Thompson, Bailen, et al., | |||

| 8 | Lamers et al., | 平均每个被试完成了56次问卷测量中的44次, 平均完成率为78.5%。 | 未报告 | 1) 内容效度: 条目的选择参考过去大量EMA研究和咨询了睡眠、头痛和健康等相关领域的专家。 2) 效标效度: 文章中报告:与健康对照组相比, 具有MDD终身诊断的患者悲伤、焦虑情绪的均值更大。 |

| 9 | Köhling et al., | 所有参与者平均问卷完成率为94.8%。 | 1) PA的个体间信度RKF为0.98, 个体内信度RC为0.81。 2) NA的个体间信度RKF为0.99, 个体内信度RC为0.80。 | 依据情绪环状模型和过去相关研究选择情绪条目。 |

| 10 | Sheets & Armey, | 平均问卷完成率为63%。 | NA的个体间信度为0.97, 个体内信度为0.78。 | 1) 从过去相关研究的量表中选择问卷条目。 2) 效标效度: 文章中报告了健康对照组、处于抑郁症缓解期组和MDD患者组在NA均值存在组间差异。 |

| 11 | van Winkel et al., | 基线阶段的EMA平均问卷完成率为85%, 追踪阶段的EMA平均问卷完成率为81%。 | PA的Cronbach’s α为0.97, NA的Cronbach’s α为0.95。基线数据的主成分分析得到的两个特征值大于1的因子可以分别解释81%的情绪个体间方差和46%的情绪个体内方差。 | 结构效度: 基线数据的主成分分析得到了两个特征值大于1的因子, 分别为积极情绪和消极情绪潜因子。 |

| 12 | Shin et al., | EMA数据集的平均问卷完成率为80%, 平均每人填写57次问卷, 标准差为13。 | 未报告 | 1) 依据情绪环状模型选择涵盖不同效价和唤醒程度的情绪条目。 2) 效标效度: EMA得到的NA和PA的网络密度都在人口学特征和情绪均值、标准差之上显著预测个体的诊断状态。 |

| 13 | Schricker et al., | 平均问卷完成率为91.1%, 标准差为9.4, 范围为48%到100%。 | 1) PA的个体内信度为0.60; 个体间信度为0.99。 2) NA的个体内信度为0.69; 个体间信度为0.98。 3) 所有EMA条目的ICC在0.44到0.66之间。 | 1) 依据PANAS量表和从过去相关研究选择情绪条目。 2) 效标效度: 文章中报告了EMA变量的组间差异。 |

| 14 | Khazanov et al., | 平均问卷完成率为72%, 标准差为12.7, 范围为41%到98%。 | 1) 验证性因子模型得到的各PA条目的个体内信度ω在0.63到0.72之间。 2) 验证性因子模型得到的各NA条目的个体内信度ω在0.75到0.77之间。 | 1) 依据PANAS量表选择情绪条目。 2) 结构效度: EMA测得瞬时PA和PANAS测得的特质PA之间的相关性在0.60到0.63之间。EMA测得瞬时NA和PANAS测得的特质NA之间的相关性在0.60到0.61之间。 |

| 15 | Crowe et al., | 共收集到了2548份问卷, MDD患者平均每人填写33.1份有效问卷, 健康对照组平均每人填写36.5份有效问卷。 | 1) 多水平探索性因素分析得到的PA的个体间信度为0.82, 个体内信度为0.46。 2) 多水平探索性因素分析得到的NA的个体间信度为0.84, 个体内信度为0.50。 3) PA的ICC为0.62, NA的ICC为0.75。 | 结构效度: 多水平探索性因素分析的结果表明:个体内和个体间层级都存在积极情绪和消极情绪双因子结构。 |

| 16 | Panaite et al., | 未报告 | DA的ICC为0.83。 | 1) 参考过去研究选择条目。 2) 效标效度: 文章中报告:相比于健康对照组, MDD患者EMA测得的烦躁情绪均值更大。 |

| 17 | Tomko et al., | 平均问卷完成率为86%, 平均每个参与者填写了147.1次问卷。 | MDD患者组NA的ICC为0.60, BPD患者组NA的ICC为0.66。 | 选择PANAS量表中的条目作为EMA施测条目。 |

| 18 | Wigman et al., | 未报告 | 未报告 | 效标效度: 正文中 |

| 报告 比率 | 15/18 | 13/18 | 18/18 |

| 序号 | 文献 | 依从性 | 信度 | 效度 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heininga et al., | 问卷填写依从率达到89%。 | PA的个体内Cronbach’s α = 0.03, 个体间Cronbach’s α = 0.99 | 效标效度: 文章中报告:与健康对照组相比, 伴有快感缺失的MDD患者PA均值更低。 |

| 2 | Schoevers et al., | 发给所有被试的所有问卷中, 仅8.72%缺失。93%的参与者填写率超过80%。 | 未报告 | 1) 效标效度: 文章中报告:当前患有MDD/AD患者NA均值最高, 其次是缓解期个体, 最后是健康对照组。PA则相反。该文献的附录提供了各情绪条目在3个组别中的均值。 2) 结构效度: 附录中提供了各情绪条目和PA、NA总分之间的相关系数。 |

| 3 | Minaeva et al., | 621个被试中, 有610个被试完成了EMA测量。 | 1) PA的个体内omega为0.79; 个体间omega为0.95。 2) NA的个体内omega为0.68; 个体间omega为0.91。 | 1) 效标效度: 正文表格1表明:MDD患者的NA中位数最大, 其次是缓解期个体, 最后是健康对照组。PA均值则相反。 2) 结构效度: 该研究选择过往研究在PA、NA潜因子上具有最高因子负荷和个体内变异性的条目。 |

| 4 | Pe et al., | 未报告 | 未报告 | 效标效度: 文章中报告:MDD患者的NA网络密度大于健康对照组。 |

| 5 | Thompson, Liu, et al., | 平均问卷完成率为74.8%, 标准差18.3%, 范围在20%到99%。 | 通过混合模型得到PA的Cronbach’s α为0.65, NA的Cronbach’s α为0.74。PA和NA具有足够的个体内变异性, PA的ICC为0.42, NA的ICC为0.43。 | 效标效度: 1) 文章中报告了健康对照组、处于抑郁症缓解期组和MDD患者组在NA和PA均值存在组间差异。 2) 正文 |

| 6 | J. Nelson et al., | 抑郁症组EMA问卷完成率为90%, 健康对照组完成率为87%。 | ICC的结果表明:对于PA, 71%的总方差是个体间方差, 29%的总方差是个体内方差。对于NA, 66%的总方差是个体间方差, 34%的总方差是个体内方差。 | 结构效度: 探索性因素分析的结果表明:情绪问卷是双因子结构, PA和NA分别是两个因子。 |

| 7 | Thompson, Bailen, et al., | |||

| 8 | Lamers et al., | 平均每个被试完成了56次问卷测量中的44次, 平均完成率为78.5%。 | 未报告 | 1) 内容效度: 条目的选择参考过去大量EMA研究和咨询了睡眠、头痛和健康等相关领域的专家。 2) 效标效度: 文章中报告:与健康对照组相比, 具有MDD终身诊断的患者悲伤、焦虑情绪的均值更大。 |

| 9 | Köhling et al., | 所有参与者平均问卷完成率为94.8%。 | 1) PA的个体间信度RKF为0.98, 个体内信度RC为0.81。 2) NA的个体间信度RKF为0.99, 个体内信度RC为0.80。 | 依据情绪环状模型和过去相关研究选择情绪条目。 |

| 10 | Sheets & Armey, | 平均问卷完成率为63%。 | NA的个体间信度为0.97, 个体内信度为0.78。 | 1) 从过去相关研究的量表中选择问卷条目。 2) 效标效度: 文章中报告了健康对照组、处于抑郁症缓解期组和MDD患者组在NA均值存在组间差异。 |

| 11 | van Winkel et al., | 基线阶段的EMA平均问卷完成率为85%, 追踪阶段的EMA平均问卷完成率为81%。 | PA的Cronbach’s α为0.97, NA的Cronbach’s α为0.95。基线数据的主成分分析得到的两个特征值大于1的因子可以分别解释81%的情绪个体间方差和46%的情绪个体内方差。 | 结构效度: 基线数据的主成分分析得到了两个特征值大于1的因子, 分别为积极情绪和消极情绪潜因子。 |

| 12 | Shin et al., | EMA数据集的平均问卷完成率为80%, 平均每人填写57次问卷, 标准差为13。 | 未报告 | 1) 依据情绪环状模型选择涵盖不同效价和唤醒程度的情绪条目。 2) 效标效度: EMA得到的NA和PA的网络密度都在人口学特征和情绪均值、标准差之上显著预测个体的诊断状态。 |

| 13 | Schricker et al., | 平均问卷完成率为91.1%, 标准差为9.4, 范围为48%到100%。 | 1) PA的个体内信度为0.60; 个体间信度为0.99。 2) NA的个体内信度为0.69; 个体间信度为0.98。 3) 所有EMA条目的ICC在0.44到0.66之间。 | 1) 依据PANAS量表和从过去相关研究选择情绪条目。 2) 效标效度: 文章中报告了EMA变量的组间差异。 |

| 14 | Khazanov et al., | 平均问卷完成率为72%, 标准差为12.7, 范围为41%到98%。 | 1) 验证性因子模型得到的各PA条目的个体内信度ω在0.63到0.72之间。 2) 验证性因子模型得到的各NA条目的个体内信度ω在0.75到0.77之间。 | 1) 依据PANAS量表选择情绪条目。 2) 结构效度: EMA测得瞬时PA和PANAS测得的特质PA之间的相关性在0.60到0.63之间。EMA测得瞬时NA和PANAS测得的特质NA之间的相关性在0.60到0.61之间。 |

| 15 | Crowe et al., | 共收集到了2548份问卷, MDD患者平均每人填写33.1份有效问卷, 健康对照组平均每人填写36.5份有效问卷。 | 1) 多水平探索性因素分析得到的PA的个体间信度为0.82, 个体内信度为0.46。 2) 多水平探索性因素分析得到的NA的个体间信度为0.84, 个体内信度为0.50。 3) PA的ICC为0.62, NA的ICC为0.75。 | 结构效度: 多水平探索性因素分析的结果表明:个体内和个体间层级都存在积极情绪和消极情绪双因子结构。 |

| 16 | Panaite et al., | 未报告 | DA的ICC为0.83。 | 1) 参考过去研究选择条目。 2) 效标效度: 文章中报告:相比于健康对照组, MDD患者EMA测得的烦躁情绪均值更大。 |

| 17 | Tomko et al., | 平均问卷完成率为86%, 平均每个参与者填写了147.1次问卷。 | MDD患者组NA的ICC为0.60, BPD患者组NA的ICC为0.66。 | 选择PANAS量表中的条目作为EMA施测条目。 |

| 18 | Wigman et al., | 未报告 | 未报告 | 效标效度: 正文中 |

| 报告 比率 | 15/18 | 13/18 | 18/18 |

| *为纳入系统综述的文献 | |

| [1] | Allen, N. B., & Sheeber, L. B. (2008). The importance of affective development for the emergence of depressive disorders during adolescence. In L. B. Sheeber & N. B. Allen (Eds.), Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders (pp. 1-10). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . |

| [2] | American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: Author. |

| [3] |

Austin, M.-P., Mitchell, P., & Goodwin, G. M. (2001). Cognitive deficits in depression: Possible implications for functional neuropathology. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 178(3), 200-206.

doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.3.200 URL |

| [4] | Barrett, L. F., Gross, J., Christensen, T. C., & Benvenuto, M. (2001). Knowing what you’re feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognition & Emotion, 15(6), 713-724. |

| [5] | Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press. |

| [6] |

Booij, S. H., Snippe, E., Jeronimus, B. F., Wichers, M., & Wigman, J. T. W. (2018). Affective reactivity to daily life stress: Relationship to positive psychotic and depressive symptoms in a general population sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 474-481.

doi: S0165-0327(17)30550-5 pmid: 28863300 |

| [7] |

Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 5-13.

doi: 10.1002/wps.v16.1 URL |

| [8] |

Bringmann, L. F., Pe, M. L., Vissers, N., Ceulemans, E., Borsboom, D., Vanpaemel, W., Tuerlinckx, F., & Kuppens, P. (2016). Assessing temporal emotion dynamics using networks. Assessment, 23(4), 425-435.

doi: 10.1177/1073191116645909 pmid: 27141038 |

| [9] |

Burcusa, S. L., & Iacono, W. G. (2007). Risk for recurrence in depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(8), 959-985.

doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.02.005 pmid: 17448579 |

| [10] |

Bylsma, L. M., Morris, B. H., & Rottenberg, J. (2008). A meta-analysis of emotional reactivity in major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(4), 676-691.

doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.001 pmid: 18006196 |

| [11] |

Carver, C. S. (2015). Control processes, priority management, and affective dynamics. Emotion Review, 7(4), 301-307.

doi: 10.1177/1754073915590616 URL |

| [12] |

Carver, C. S., Sutton, S. K., & Scheier, M. F. (2000). Action, emotion, and personality: Emerging conceptual integration. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(6), 741-751.

doi: 10.1177/0146167200268008 URL |

| [13] | Colombo, D., Fernández-Álvarez, J., Patané, A., Semonella, M., Kwiatkowska, M., García-Palacios, A., Cipresso, P., Riva, G., & Botella, C. (2019). Current state and future directions of technology-based ecological momentary assessment and intervention for major depressive disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(4), 465. |

| [14] |

Connolly, S. L., & Alloy, L. B. (2017). Rumination interacts with life stress to predict depressive symptoms: An ecological momentary assessment study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 97, 86-95.

doi: S0005-7967(17)30140-7 pmid: 28734979 |

| [15] |

* Crowe, E., Daly, M., Delaney, L., Carroll, S., & Malone, K. M. (2019). The intra-day dynamics of affect, self-esteem, tiredness, and suicidality in major depression. Psychiatry Research, 279, 98-108.

doi: S0165-1781(17)30094-X pmid: 29661498 |

| [16] |

Dakos, V., Scheffer, M., van Nes, E. H., Brovkin, V., Petoukhov, V., & Held, H. (2008). Slowing down as an early warning signal for abrupt climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(38), 14308-14312.

doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802430105 URL |

| [17] |

Dejonckheere, E., Mestdagh, M., Houben, M., Erbas, Y., Pe, M., Koval, P., Brose, A., Bastian, B., & Kuppens, P. (2018). The bipolarity of affect and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(2), 323-341.

doi: 10.1037/pspp0000186 pmid: 29389216 |

| [18] |

Dejonckheere, E., Mestdagh, M., Houben, M., Rutten, I., Sels, L., Kuppens, P., & Tuerlinckx, F. (2019). Complex affect dynamics add limited information to the prediction of psychological well-being. Nature Human Behaviour, 3(5), 478-491.

doi: 10.1038/s41562-019-0555-0 pmid: 30988484 |

| [19] |

Dejonckheere, E., Mestdagh, M., Kuppens, P., & Tuerlinckx, F. (2020). Reply to: Context matters for affective chronometry. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(7), 690-693.

doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0861-6 pmid: 32341492 |

| [20] |

Dejonckheere, E., Mestdagh, M., Verdonck, S., Lafit, G., Ceulemans, E., Bastian, B., & Kalokerinos, E. K. (2021). The relation between positive and negative affect becomes more negative in response to personally relevant events. Emotion, 21(2), 326-336.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000697 URL |

| [21] |

Demiralp, E., Thompson, R. J., Mata, J., Jaeggi, S. M., Buschkuehl, M., Barrett, L. F., Ellsworth, P. C., Demiralp, M., Hernandez-Garcia, L., Deldin, P. J., Gotlib, I. H., & Jonides, J. (2012). Feeling blue or turquoise? Emotional differentiation in major depressive disorder. Psychological Science, 23(11), 1410-1416.

doi: 10.1177/0956797612444903 pmid: 23070307 |

| [22] |

Eisele, G., Lafit, G., Vachon, H., Kuppens, P., Houben, M., Myin-Germeys, I., & Viechtbauer, W. (2021). Affective structure, measurement invariance, and reliability across different experience sampling protocols. Journal of Research in Personality, 92, 104094.

doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104094 URL |

| [23] |

Epskamp, S., van Borkulo, C. D., van der Veen, D. C., Servaas, M. N., Isvoranu, A.-M., Riese, H., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2018). Personalized network modeling in psychopathology: The importance of contemporaneous and temporal connections. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(3), 416-427.

doi: 10.1177/2167702617744325 pmid: 29805918 |

| [24] | Fernandes, B. S., Williams, L. M., Steiner, J., Leboyer, M., Carvalho, A. F., & Berk, M. (2017). The new field of ‘precision psychiatry’. BMC Medicine, 15(1), 80. |

| [25] |

Fisher, A. J., Reeves, J. W., Lawyer, G., Medaglia, J. D., & Rubel, J. A. (2017). Exploring the idiographic dynamics of mood and anxiety via network analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(8), 1044-1056.

doi: 10.1037/abn0000311 pmid: 29154565 |

| [26] |

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172-175.

doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00431 pmid: 11934003 |

| [27] |

Geldhof, G. J., Preacher, K. J., & Zyphur, M. J. (2014). Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychological Methods, 19(1), 72-91.

doi: 10.1037/a0032138 pmid: 23646988 |

| [28] |

Girolamo, G., Barattieri di San Pietro, C., Bulgari, V., Dagani, J., Ferrari, C., Hotopf, M.,... Zarbo, C. (2020). The acceptability of real-time health monitoring among community participants with depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Depression and Anxiety, 37(9), 885-897.

doi: 10.1002/da.v37.9 URL |

| [29] | Grillon, C., Franco-Chaves, J. A., Mateus, C. F., Ionescu, D. F., & Zarate, C. A. (2013). Major depression is not associated with blunting of aversive responses; evidence for enhanced anxious anticipation. PloS ONE, 8(8), e70969. |

| [30] | Gross, J. J., & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation:Conceptual foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3-24). The Guilford Press |

| [31] |

Grosse Rueschkamp, J. M., Kuppens, P., Riediger, M., Blanke, E. S., & Brose, A. (2020). Higher well-being is related to reduced affective reactivity to positive events in daily life. Emotion, 20(3), 376-390.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000557 pmid: 30550304 |

| [32] |

Hamaker, E. L., Asparouhov, T., Brose, A., Schmiedek, F., & Muthén, B. (2018). At the frontiers of modeling intensive longitudinal data: Dynamic structural equation models for the affective measurements from the COGITO study. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53(6), 820-841.

doi: 10.1080/00273171.2018.1446819 pmid: 29624092 |

| [33] |

Hasselhorn, K., Ottenstein, C., & Lischetzke, T. (2021). The effects of assessment intensity on participant burden, compliance, within-person variance, and within-person relationships in ambulatory assessment. Behavior Research Methods, 54(4), 1541-1558.

doi: 10.3758/s13428-021-01683-6 pmid: 34505997 |

| [34] |

* Heininga, V. E., Dejonckheere, E., Houben, M., Obbels, J., Sienaert, P., Leroy, B., van Roy, J., & Kuppens, P. (2019). The dynamical signature of anhedonia in major depressive disorder: Positive emotion dynamics, reactivity, and recovery. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 1-11.

doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1996-0 |

| [35] |

Heron, K. E., & Smyth, J. M. (2010). Ecological momentary interventions: Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(1), 1-39.

doi: 10.1348/135910709X466063 URL |

| [36] |

Herrman, H., Patel, V., Kieling, C., Berk, M., Buchweitz, C., Cuijpers, P.,... Wolpert, M. (2022). Time for united action on depression: A Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. The Lancet, 399(10328), 957-1022.

doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02141-3 URL |

| [37] |

Honkalampi, K., Hintikka, J., Saarinen, P., Lehtonen, J., & Viinamäki, H. (2000). Is alexithymia a permanent feature in depressed patients? Results from a 6-month follow-up study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 69(6), 303-308.

doi: 10.1159/000012412 pmid: 11070442 |

| [38] |

Houben, M., & Kuppens, P. (2020). Emotion dynamics and the association with depressive features and borderline personality disorder traits: Unique, specific, and prospective relationships. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(2), 226-239.

doi: 10.1177/2167702619871962 URL |

| [39] |

Houben, M., van den Noortgate, W., & Kuppens, P. (2015). The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 901-930.

doi: 10.1037/a0038822 pmid: 25822133 |

| [40] |

Huang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Yu, X., Yan, J.,... Wu, Y. (2019). Prevalence of mental disorders in China: A cross-sectional epidemiological study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(3), 211-224.

doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X URL |

| [41] |

Ismaylova, E., Di Sante, J., Gouin, J.-P., Pomares, F. B., Vitaro, F., Tremblay, R. E., & Booij, L. (2018). Associations between daily mood states and brain gray matter volume, resting-state functional connectivity and task-based activity in healthy adults. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 168.

doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00168 pmid: 29765312 |

| [42] |

Jahng, S., Wood, P. K., & Trull, T. J. (2008). Analysis of affective instability in ecological momentary assessment: Indices using successive difference and group comparison via multilevel modeling. Psychological Methods, 13(4), 354-375.

doi: 10.1037/a0014173 pmid: 19071999 |

| [43] |

James, S. L., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N.,... Murray, C. J. L. (2018). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 Diseases and Injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 392(10159), 1789-1858.

doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 URL |

| [44] |

Jenkins, B. N., Hunter, J. F., Richardson, M. J., Conner, T. S., & Pressman, S. D. (2020). Affect variability and predictability: Using recurrence quantification analysis to better understand how the dynamics of affect relate to health. Emotion, 20(3), 391-402.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000556 pmid: 30714779 |

| [45] |

Kashdan, T. B., & Farmer, A. S. (2014). Differentiating emotions across contexts: Comparing adults with and without social anxiety disorder using random, social interaction, and daily experience sampling. Emotion, 14(3), 629-638.

doi: 10.1037/a0035796 pmid: 24512246 |

| [46] |

Keng, S.-L., Tong, E. M., Yan, E. T. L., Ebstein, R. P., & Lai, P.-S. (2021). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on affect dynamics: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 12(6), 1490-1501.

doi: 10.1007/s12671-021-01617-5 |

| [47] |

* Khazanov, G. K., Ruscio, A. M., & Swendsen, J. (2019). The “brightening” effect: Reactions to positive events in the daily lives of individuals with major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 50(2), 270-284.

doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2018.05.008 URL |

| [48] |

Khoury, M. J., & Galea, S. (2016). Will precision medicine improve population health?. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 316(13), 1357-1358.

doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12260 URL |

| [49] |

* Köhling, J., Moessner, M., Ehrenthal, J. C., Bauer, S., Cierpka, M., Kämmerer, A., Schauenburg, H., & Dinger, U. (2016). Affective instability and reactivity in depressed patients with and without borderline pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(6), 776-795.

doi: 10.1521/pedi_2015_29_230 pmid: 26623534 |

| [50] | Koval, P., Kuppens, P., Allen, N. B., & Sheeber, L. (2012). Getting stuck in depression: The roles of rumination and emotional inertia. Cognition & Emotion, 26(8), 1412-1427. |

| [51] |

Kuppens, P., Allen, N. B., & Sheeber, L. B. (2010). Emotional inertia and psychological maladjustment. Psychological Science, 21(7), 984-991.

doi: 10.1177/0956797610372634 pmid: 20501521 |

| [52] |

Kuppens, P., & Verduyn, P. (2015). Looking at emotion regulation through the window of emotion dynamics. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 72-79.

doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2015.960505 URL |

| [53] |

Kuppens, P., & Verduyn, P. (2017). Emotion dynamics. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 22-26.

doi: S2352-250X(16)30201-9 pmid: 28950968 |

| [54] |

* Lamers, F., Swendsen, J., Cui, L., Husky, M., Johns, J., Zipunnikov, V., & Merikangas, K. R. (2018). Mood reactivity and affective dynamics in mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 659-669.

doi: 10.1037/abn0000378 pmid: 30335438 |

| [55] |

Lapate, R. C., & Heller, A. S. (2020). Context matters for affective chronometry. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(7), 688-689.

doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0860-7 pmid: 32341491 |

| [56] |

Liu, D. Y., Gilbert, K. E., & Thompson, R. J. (2020). Emotion differentiation moderates the effects of rumination on depression: A longitudinal study. Emotion, 20(7), 1234-1243.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000627 pmid: 31246044 |

| [57] |

Lydon-Staley, D. M., Xia, M., Mak, H. W., & Fosco, G. M. (2019). Adolescent emotion network dynamics in daily life and implications for depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(4), 717-729.

doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0474-y pmid: 30203118 |

| [58] |

McKone, K. M. P., & Silk, J. S. (2022). The emotion dynamics conundrum in developmental psychopathology: Similarities, distinctions, and adaptiveness of affective variability and socioaffective flexibility. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 25(1), 44-74.

doi: 10.1007/s10567-022-00382-8 pmid: 35133523 |

| [59] |

Merikangas, K. R., Swendsen, J., Hickie, I. B., Cui, L., Shou, H., Merikangas, A. K.,... Zipunnikov, V. (2019). Real-time mobile monitoring of the dynamic associations among motor activity, energy, mood, and sleep in adults with bipolar disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(2), 190-198.

doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3546 pmid: 30540352 |

| [60] |

Mesquita, B., & Boiger, M. (2014). Emotions in context: A sociodynamic model of emotions. Emotion Review, 6(4), 298-302.

doi: 10.1177/1754073914534480 URL |

| [61] |

Mestdagh, M., & Dejonckheere, E. (2021). Ambulatory assessment in psychopathology research: Current achievements and future ambitions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 41, 1-8.

doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.01.004 pmid: 33550191 |

| [62] |

Mestdagh, M., Pe, M., Pestman, W., Verdonck, S., Kuppens, P., & Tuerlinckx, F. (2018). Sidelining the mean: The relative variability index as a generic mean-corrected variability measure for bounded variables. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 690-707.

doi: 10.1037/met0000153 pmid: 29648843 |

| [63] | * Minaeva, O., George, S. V., Kuranova, A., Jacobs, N., Thiery, E., Derom, C.,... Booij, S. H. (2021). Overnight affective dynamics and sleep characteristics as predictors of depression and its development in women. Sleep, 44(10), 1-12. |

| [64] | Mofsen, A. M., Rodebaugh, T. L., Nicol, G. E., Depp, C. A., Miller, J. P., & Lenze, E. J. (2019). When all else fails, listen to the patient: A viewpoint on the use of ecological momentary assessment in clinical trials. JMIR Mental Health, 6(5), e11845. |

| [65] | Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA, Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. |

| [66] |

Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Stratford, P. W., Knol, D. L., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. (2010). The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(7), 737-745.

doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006 pmid: 20494804 |

| [67] |

Moors, A. (2014). Flavors of appraisal theories of emotion. Emotion Review, 6(4), 303-307.

doi: 10.1177/1754073914534477 URL |

| [68] |

Myin-Germeys, I., Kasanova, Z., Vaessen, T., Vachon, H., Kirtley, O., Viechtbauer, W., & Reininghaus, U. (2018). Experience sampling methodology in mental health research: New insights and technical developments. World Psychiatry, 17(2), 123-132.

doi: 10.1002/wps.v17.2 URL |

| [69] |

Myin‐Germeys, I., Peeters, F., Havermans, R., Nicolson, N. A., DeVries, M. W., Delespaul, P., & van Os, J. (2003). Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis and affective disorder: An experience sampling study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 107(2), 124-131.

doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02025.x pmid: 12534438 |

| [70] |

Nelson, B., McGorry, P. D., Wichers, M., Wigman, J. T. W., & Hartmann, J. A. (2017). Moving from static to dynamic models of the onset of mental disorder: A review. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(5), 528-534.

doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0001 pmid: 28355471 |

| [71] |

* Nelson, J., Klumparendt, A., Doebler, P., & Ehring, T. (2020). Everyday emotional dynamics in major depression. Emotion, 20(2), 179-191.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000541 pmid: 30589297 |

| [72] |

Newman, M. G., & Llera, S. J. (2011). A novel theory of experiential avoidance in generalized anxiety disorder: A review and synthesis of research supporting a contrast avoidance model of worry. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 371-382.

doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.008 pmid: 21334285 |

| [73] | Ormel, J., VonKorff, M., Jeronimus, B. F., & Riese, H. (2017). Set-Point Theory and personality development:Resolution of a paradox. In J. Specht (Ed.), Personality development across the lifespan (pp. 117-137). Elsevier. |

| [74] | * Panaite, V., Whittington, A., & Cowden Hindash, A. (2018). The role of appraisal in dysphoric affect reactivity to positive laboratory films and daily life events in depression. Cognition & Emotion, 32(6), 1362-1373. |

| [75] |

* Pe, M. L., Kircanski, K., Thompson, R. J., Bringmann, L. F., Tuerlinckx, F., Mestdagh, M.,... Gotlib, I. H. (2015). Emotion-network density in major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(2), 292-300.

doi: 10.1177/2167702614540645 pmid: 31754552 |

| [76] |

Price, R. B., Lane, S., Gates, K., Kraynak, T. E., Horner, M. S., Thase, M. E., & Siegle, G. J. (2017). Parsing heterogeneity in the brain connectivity of depressed and healthy adults during positive mood. Biological Psychiatry, 81(4), 347-357.

doi: S0006-3223(16)32540-9 pmid: 27712830 |

| [77] |

Provenzano, J., Fossati, P., Dejonckheere, E., Verduyn, P., & Kuppens, P. (2021). Inflexibly sustained negative affect and rumination independently link default mode network efficiency to subclinical depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 293, 347-354.

doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.051 pmid: 34229288 |

| [78] |

Quoidbach, J., Gruber, J., Mikolajczak, M., Kogan, A., Kotsou, I., & Norton, M. I. (2014). Emodiversity and the emotional ecosystem. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(6), 2057-2066.

doi: 10.1037/a0038025 URL |

| [79] |

Reichert, M., Gan, G., Renz, M., Braun, U., Brüßler, S., Timm, I.,... Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2021). Ambulatory assessment for precision psychiatry: Foundations, current developments and future avenues. Experimental Neurology, 345, 113807.

doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2021.113807 URL |

| [80] |

Reitsema, A. M., Jeronimus, B. F., van Dijk, M., & de Jonge, P. (2022). Emotion dynamics in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic and descriptive review. Emotion, 22(2), 374-396.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000970 URL |

| [81] |

Rottenberg, J. (2005). Mood and emotion in major depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 167-170.

doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00354.x URL |

| [82] |

Rottenberg, J. (2017). Emotions in depression: What do we really know?. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13(1), 241-263.

doi: 10.1146/clinpsy.2017.13.issue-1 URL |

| [83] |

Ruscio, A. M., Gentes, E. L., Jones, J. D., Hallion, L. S., Coleman, E. S., & Swendsen, J. (2015). Rumination predicts heightened responding to stressful life events in major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(1), 17-26.

doi: 10.1037/abn0000025 pmid: 25688429 |

| [84] |

Scheffer, M., Bascompte, J., Brock, W. A., Brovkin, V., Carpenter, S. R., Dakos, V.,... Sugihara, G. (2009). Early-warning signals for critical transitions. Nature, 461(7260), 53-59.

doi: 10.1038/nature08227 |

| [85] |

Schick, A., Rauschenberg, C., Ader, L., Daemen, M., Wieland, L. M., Paetzold, I.,... Reininghaus, U. (2023). Novel digital methods for gathering intensive time series data in mental health research: Scoping review of a rapidly evolving field. Psychological Medicine, 53(1), 55-65.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291722003336 URL |

| [86] |

* Schoevers, R. A., van Borkulo, C. D., Lamers, F., Servaas, M. N., Bastiaansen, J. A., Beekman, A. T. F.,... Riese, H. (2021). Affect fluctuations examined with ecological momentary assessment in patients with current or remitted depression and anxiety disorders. Psychological Medicine, 51(11), 1906-1915.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291720000689 URL |

| [87] |

* Schricker, I. F., Nayman, S., Reinhard, I., & Kuehner, C. (2022). Reciprocal prospective effects of momentary cognitions and affect in daily life and mood reactivity toward daily events in remitted recurrent depression. Behavior Therapy, 54(2), 274-289.

doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2022.09.001 URL |

| [88] |

Seah, T. H. S., & Coifman, K. G. (2022). Emotion differentiation and behavioral dysregulation in clinical and nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Emotion, 22(7), 1686-1697.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000968 URL |

| [89] |

Servaas, M. N., Riese, H., Renken, R. J., Wichers, M., Bastiaansen, J. A., Figueroa, C. A.,... Ruhé, H. (2017). Associations between daily affective instability and connectomics in functional subnetworks in remitted patients with recurrent major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(13), 2583-2592.

doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.65 pmid: 28361870 |

| [90] | * Sheets, E. S., & Armey, M. F. (2020). Daily interpersonal and noninterpersonal stress reactivity in current and remitted depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 44(4), 774-787. |

| [91] |

* Shin, K. E., Newman, M. G., & Jacobson, N. C. (2022). Emotion network density is a potential clinical marker for anxiety and depression: Comparison of ecological momentary assessment and daily diary. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(S1), 31-50.

doi: 10.1111/bjc.v61.s1 URL |

| [92] | Simons, C. J. P., Drukker, M., Evers, S.,van, Mastrigt, G. A. P. G., Höhn, P., Kramer, I., Wichers, M.(2017). Economic evaluation of an experience sampling method intervention in depression compared with treatment as usual using data from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 415. |

| [93] |

Sliwinski, M. J., Almeida, D. M., Smyth, J., & Stawski, R. S. (2009). Intraindividual change and variability in daily stress processes: Findings from two measurement-burst diary studies. Psychology and Aging, 24(4), 828-840.

doi: 10.1037/a0017925 pmid: 20025399 |

| [94] |

Sperry, S. H., & Kwapil, T. R. (2019). Affective dynamics in bipolar spectrum psychopathology: Modeling inertia, reactivity, variability, and instability in daily life. Journal of Affective Disorders, 251, 195-204.

doi: S0165-0327(18)31748-8 pmid: 30927580 |

| [95] |

Sperry, S. H., Walsh, M. A., & Kwapil, T. R. (2020). Emotion dynamics concurrently and prospectively predict mood psychopathology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 261, 67-75.

doi: S0165-0327(19)30800-6 pmid: 31600589 |

| [96] |

Starr, L. R., Hershenberg, R., Li, Y. I., & Shaw, Z. A. (2017). When feelings lack precision: Low positive and negative emotion differentiation and depressive symptoms in daily life. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(4), 613-631.

doi: 10.1177/2167702617694657 URL |

| [97] |

Ten Have, M., de Graaf, R., van Dorsselaer, S., Tuithof, M., Kleinjan, M., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2018). Recurrence and chronicity of major depressive disorder and their risk indicators in a population cohort. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 137(6), 503-515.

doi: 10.1111/acps.12874 pmid: 29577236 |

| [98] |

* Thompson, R. J., Bailen, N. H., & English, T. (2021). Everyday emotional experiences in current and remitted major depressive disorder: An experience-sampling study. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(5), 866-878.

doi: 10.1177/2167702621992082 URL |

| [99] |

Thompson, R. J., Berenbaum, H., & Bredemeier, K. (2011). Cross-sectional and longitudinal relations between affective instability and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130(1-2), 53-59.

doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.021 pmid: 20951438 |

| [100] |

* Thompson, R. J., Liu, D. Y., Sudit, E., & Boden, M. (2021). Emotion differentiation in current and remitted major depressive disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 685851.

doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.685851 URL |

| [101] |

* Tomko, R. L., Lane, S. P., Pronove, L. M., Treloar, H. R., Brown, W. C., Solhan, M. B., Wood, P. K., & Trull, T. J. (2015). Undifferentiated negative affect and impulsivity in borderline personality and depressive disorders: A momentary perspective. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 124(3), 740-753.

doi: 10.1037/abn0000064 pmid: 26147324 |

| [102] |

Tracy, J. L. (2014). An evolutionary approach to understanding distinct emotions. Emotion Review, 6(4), 308-312.

doi: 10.1177/1754073914534478 URL |

| [103] |

Trull, T. J., & Ebner-Priemer, U. W. (2020). Ambulatory assessment in psychopathology research: A review of recommended reporting guidelines and current practices. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(1), 56-63.

doi: 10.1037/abn0000473 pmid: 31868388 |

| [104] |

Trull, T. J., Lane, S. P., Koval, P., & Ebner-Priemer, U. W. (2015). Affective dynamics in psychopathology. Emotion Review, 7(4), 355-361.

pmid: 27617032 |

| [105] |

Urban-Wojcik, E. J., Mumford, J. A., Almeida, D. M., Lachman, M. E., Ryff, C. D., Davidson, R. J., & Schaefer, S. M. (2022). Emodiversity, health, and well-being in the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) daily diary study. Emotion, 22(4), 603-615.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000753 URL |

| [106] |

van de Leemput, I. A., Wichers, M., Cramer, A. O., Borsboom, D., Tuerlinckx, F., Kuppens, P.,... Scheffer, M. (2014). Critical slowing down as early warning for the onset and termination of depression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(1), 87-92.

doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312114110 URL |

| [107] |

van der Gucht, K., Dejonckheere, E., Erbas, Y., Takano, K., Vandemoortele, M., Maex, E., Raes, F., & Kuppens, P. (2019). An experience sampling study examining the potential impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on emotion differentiation. Emotion, 19(1), 123-131.

doi: 10.1037/emo0000406 pmid: 29578747 |

| [108] | van Genugten, C. R., Schuurmans, J., Lamers, F., Riese, H., Penninx, B. W. J. H., Schoevers, R. A., Riper, H. M., & Smit, J. H. (2020). Experienced burden of and adherence to smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment in persons with affective disorders. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(2), 322. |

| [109] | * van Winkel, M., Nicolson, N. A., Wichers, M., Viechtbauer, W., Myin-Germeys, I., & Peeters, F. (2015). Daily life stress reactivity in remitted versus non-remitted depressed individuals. European Psychiatry, 30(4), 441-447. |

| [110] | Waffenschmidt, S., Knelangen, M., Sieben, W., Bühn, S., & Pieper, D. (2019). Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: A methodological systematic review. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 132. |

| [111] |

Walker, E. R., McGee, R. E., & Druss, B. G. (2015). Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(4), 334-341.

doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502 pmid: 25671328 |

| [112] | Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa. |

| [113] |

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Carey, G. (1988). Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97(3), 346-353.

doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.346 pmid: 3192830 |

| [114] |

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063-1070.

doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 pmid: 3397865 |

| [115] |

Watson, D., & Tellegen, A. (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 219-235.

doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.219 pmid: 3901060 |

| [116] | Wayda-Zalewska, M., Grzegorzewski, P., Kot, E., Skimina, E., Santangelo, P. S., & Kucharska, K. (2022). Emotion dynamics and emotion regulation in anorexia nervosa: A systematic review of ecological momentary assessment studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13659. |

| [117] |

Wendt, L. P., Wright, A. G. C., Pilkonis, P. A., Woods, W. C., Denissen, J. J. A., Kühnel, A., & Zimmermann, J. (2020). Indicators of affect dynamics: Structure, reliability, and personality correlates. European Journal of Personality, 34(6), 1060-1072.

doi: 10.1002/per.2277 URL |

| [118] |

Wichers, M. (2014). The dynamic nature of depression: A new micro-level perspective of mental disorder that meets current challenges. Psychological Medicine, 44(7), 1349-1360.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001979 pmid: 23942140 |

| [119] |

Wichers, M., Groot, P. C., Psychosystems, ESM, Group, & EWS, Group.(2016). Critical slowing down as a personalized early warning signal for depression. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(2), 114-116.

doi: 10.1159/000441458 pmid: 26821231 |

| [120] |

Wichers, M., Wigman, J. T. W., & Myin-Germeys, I. (2015). Micro-level affect dynamics in psychopathology viewed from complex dynamical system theory. Emotion Review, 7(4), 362-367.

doi: 10.1177/1754073915590623 URL |

| [121] |

* Wigman, J. T. W., van Os, J., Borsboom, D., Wardenaar, K. J., Epskamp, S., Klippel, A.,... Wichers, M. (2015). Exploring the underlying structure of mental disorders: Cross-diagnostic differences and similarities from a network perspective using both a top-down and a bottom-up approach. Psychological Medicine, 45(11), 2375-2387.

doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000331 pmid: 25804221 |

| [122] |

Willroth, E. C., Flett, J. A. M., & Mauss, I. B. (2020). Depressive symptoms and deficits in stress-reactive negative, positive, and within-emotion-category differentiation: A daily diary study. Journal of Personality, 88(2), 174-184.

doi: 10.1111/jopy.12475 pmid: 30927441 |

| [123] |

Wright, A. G. C., Gates, K. M., Arizmendi, C., Lane, S. T., Woods, W. C., & Edershile, E. A. (2019). Focusing personality assessment on the person: Modeling general, shared, and person specific processes in personality and psychopathology. Psychological Assessment, 31(4), 502-515.

doi: 10.1037/pas0000617 pmid: 30920277 |

| [124] |

Zimmermann, J., Woods, W. C., Ritter, S., Happel, M., Masuhr, O., Jaeger, U., Spitzer, C., & Wright, A. G. C. (2019). Integrating structure and dynamics in personality assessment: First steps toward the development and validation of a personality dynamics diary. Psychological Assessment, 31(4), 516-531.

doi: 10.1037/pas0000625 pmid: 30869961 |

| [1] | WU Caizhi, YUN Yun, XIAO Zhihua, ZHOU Zhongying, TONG Ting, REN Zhihong. The application of ecological momentary assessment in suicide research [J]. Advances in Psychological Science, 2024, 32(12): 2067-2090. |

| [2] | CHEN Mingrui; ZHOU Ping. Ecological momentary assessment and intervention of substance use [J]. Advances in Psychological Science, 2017, 25(2): 247-252. |

| [3] | WANG Xiaole; WANG Donglin. Hypothalamic Abnormalities and Major Depressive Disorder [J]. Advances in Psychological Science, 2015, 23(10): 1763-1774. |

| [4] | JIANG Guang-Rong;YU Li-Xia;ZHENG Ying;FENG Yu;LING Xiao. The Current Status, Problems and Recommendations on Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in China [J]. , 2011, 19(6): 861-873. |

| [5] | Feng Danjun,Shi Lin. Introduction of Ecological Momentary Assessment and Other Methods for Measuring Coping Ways [J]. , 2004, 12(3): 429-434. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||