1 引言

国家安全监管总局、交通运输部联合发布的《道路交通运输安全发展报告(2017)》显示, 2016年中国共接报道路交通事故864.3万起, 同比增加65.9万起, 上升16.5%。美国交通安全基金会调查指出, 超过55%的致命性事故, 是由驾驶员潜在的攻击性驾驶行为引发的, 78%的受访者将攻击性驾驶看作严重的交通安全问题, 但是仍然有22%~26%的受访者在近期内曾有过紧跟前方车辆、迫使其他驾驶员加速等攻击性驾驶行为(AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety, 2009)。Mann等(2007)的调查结果表明, 自我报告曾有过攻击性行为的驾驶员, 碰撞风险增加了一倍。根据剂量反应模式, 驾驶员攻击性行为越严重, 事故可能性越高(Sansone, Leung, & Wiederman, 2012; Wickens, Mann, Ialomiteanu, & Stoduto, 2016)。在我国, 攻击性驾驶已成为社会关注的热点(交通运输部公路科学研究院, 中瑞交通安全研究中心, 2015)。如何通过减少驾驶员的攻击性驾驶行为来降低交通事故率, 是交通心理学研究的一个复杂而重要的课题。

道路是社会情境的缩影, 与日常人际交流不同, 汽车的封闭性影响了驾驶员对其他道路使用者社会存在的感知, 强化了领域概念, 并阻碍了驾驶员之间的社会交流(Leckie & Hopkins, 2002)。交通心理学研究者结合道路情境和驾驶任务的特殊性, 在传统社会心理学攻击理论的基础上, 分别从人格因素、情绪因素及情境因素、社会认知因素等角度, 提出了驾驶员的攻击行为理论。最早, Tillmann和Hobbs (1949)发现, 日常生活中具有攻击性的人往往承担更多的事故责任, 由此提出社会失调理论, 开创了攻击性驾驶行为研究的先河(Galovski & Blanchard, 2002; Efrat & Shoham, 2013; Ulleberg & Rundmo, 2003)。Shinar (1998)结合人格因素、情绪因素和道路情境因素, 提出“挫折-攻击”理论; 随着社会认知理论的成熟, 众多社会心理学家应用归因理论和一般攻击模型对攻击性驾驶行为的认知和情绪机制进行解释; Soole, Lennon, Watson和Bingham (2011)整合了个性、情境、认知和情绪因素, 形成一个统一的、综合的框架来理解攻击性行为, 提出了更为复杂的综合模型。

2 攻击性驾驶行为的界定

持不同理论观点的研究者, 对攻击性驾驶行为定义的侧重点各有不同。Shinar (1998)从“挫折-攻击”理论出发, 强调攻击性驾驶行为是驾驶员在挫折情境中典型的行为表现:不考虑其他驾驶员的安全和感受, 激惹其他驾驶员, 为节省时间而牺牲他人利益的危险驾驶行为。但是, 这一定义无法将攻击性驾驶行为和疏忽驾驶、风险驾驶行为相区别。

Anderson和Bushman (2002)的一般攻击模型认为, 攻击行为是针对其他个体并伴随有伤害意图的行为, 伤害意图是攻击行为与其他危险行为相区别的标志。Soole等(2011)将一般攻击模型与“挫折-攻击”理论相结合, 提出驾驶员攻击行为的综合模型, 认为攻击性驾驶行为是驾驶员为达到某一目的, 针对其他道路使用者并以造成身体或心理伤害为意图的行为, 并且这种行为伴随愤怒或挫折等消极情绪。这一定义首先强调了攻击性驾驶行为是一种有意行为(不是判断失误或注意缺乏造成的); 第二, 将伤害意图视作攻击性驾驶行为与其他危险驾驶行为(例如, 为了节约时间或追求感官刺激而抢道)相区别的关键标志; 第三, 融合了“挫折-攻击”理论的观点, 即认为消极情绪对于定义攻击性驾驶行为同样具有重要意义。

Wickens, Mann和Wiesenthal (2013)进一步提出, 攻击性行为的第四个特点是具有违法性质(具有恐吓伤害和攻击成分), 认为攻击性驾驶行为是一种针对其他驾驶员的敌意性道路交通违规行为(紧跟前车, 粗鲁驾驶等)和愤怒表达行为(咒诅、不雅手势等), 这些行为不是由于一时的判断失误或注意缺乏引起的, 而是一种带有敌意动机性质的异常驾驶行为。以上四个标准中, 有意性被大多数研究者视为界定攻击性驾驶的关键标准, 但是, 暗藏伤害意图、伴随消极情绪并且具有违法性质, 三个条件都要满足才能算作攻击性驾驶行为吗?后三个标准是否可以作为攻击性驾驶行为的界定标准至今仍存在广泛争议, 未来只有深入探索攻击性驾驶行为的心理机制, 才能有望解决界定标准的争议。

3 综合模型的理论背景

3.1 人格因素驱动的理论模型——社会失调理论

社会失调理论来源于Tillmann和Hobbs (1949)的研究, 该理论认为, 驾驶是日常生活的一部分, 平日里具有攻击性的个体, 也会将自身的攻击倾向延伸到驾驶环境中。也就是说, 攻击倾向是一种人格模式, 势必会受到个人童年生活和社会背景的影响, 攻击性驾驶行为便是此种行为模式的表现之一。Macmillan (1975, 引自Krahé, 2005)的研究表明, 有很高犯罪率和社会问题倾向的个体, 交通事故和碰撞率也更高。Galovski和Blanchard (2002)的研究也发现, 具有反社会人格障碍的个体同时也普遍具有攻击性驾驶问题。同样的, Carroll, Davidson和Ogloff (2010)考察了暴力罪犯在人口特征、犯罪史和精神健康状况方面的特征, 结果表明罪犯的敌对知觉偏见是导致他们心理社会功能失调的主要原因, 并且极有可能延伸到驾驶情境中。社会失调理论开创了以人格理论视角解释攻击性驾驶行为的先河, 可用于描述和鉴别极端暴力的道路违法和攻击行为, 但是该理论却无法解释一般驾驶人群的轻微攻击性驾驶。

3.2 情境因素驱动的理论模型——“挫折-攻击”理论

Dollard, Miller, Doob, Mowrer和Sears (1939)最早提出了“挫折-攻击”假说:攻击永远是挫折的结果, 而挫折感则是目标指向行为受阻的结果。Shinar (1998)通过实证研究将该假说应用到驾驶情境中, 提出了驾驶员“挫折-攻击”模型, 此模型认为公路上的受阻事件(例如交通堵塞), 会诱发驾驶员的挫折感。研究发现, 驾驶员在交通拥堵情况下, 感受到更大的压力, 更频繁地出现蓄意尾随、鸣喇叭等攻击性驾驶行为(Fitzpatrick, Samuel, & Knodler, 2017; Hennessy & Wiesenthal, 1997)。Shinar和Compton (2004)使用回归分析证明了高峰时段, 驾驶员有更高水平的攻击性行为。

“挫折-攻击”理论为驾驶员攻击性行为提供了直观的解释, 但研究者们指出该理论存在三个明显缺陷。首先, 挫败感不一定随着拥堵而增加(Lajunen, Parker, & Summala, 1999); 第二, 该理论无法充分说明攻击性驾驶行为的认知、情感过程以及攻击性驾驶行为如何升级为严重事故; 第三, 该理论过于强调交通拥堵激发的挫折情绪, 忽略了道路冲突事件也会诱发焦虑、恐惧以及愤怒, 而这些消极情绪也是诱发攻击性驾驶行为的重要因素。

3.3 社会认知因素驱动的理论模型——归因理论模型

Wickens, Wiesenthal, Flora和Flett (2011)应用Weiner (2001)的社会行为归因模型, 对驾驶员攻击行为背后的认知和情绪机制进行了系统性的整合研究, 首次通过结构方程模型, 将Weiner的社会行为归因模型推广到交通心理学的研究领域, 其研究结果表明, 归因内外性、可控性和有意性能够预测责任推断, 具体来说, 内部可控有意性归因越强(例如, 被试认为情境中的抢道危险事件源于驾驶员个人因素, 在其可控范围内有意为之), 对违规驾驶员的责任推断也越强。责任推断是归因倾向影响情绪和行为倾向的中介因素, 责任推断越强, 被试产生的愤怒情绪和攻击性意图越强; 责任推断越弱, 产生的同情和亲社会意图越强, 即责任推断能够正向预测愤怒和攻击意图, 负向预测同情和亲社会意图。

归因理论从社会认知的视角解释了归因、责任推断、愤怒情绪与攻击性驾驶行为的因果关系, 其解释的一般模式是, 首先将卷入攻击性驾驶事件的双方区分为“受害者”和“肇事者”, 然后强调“受害者”是如何在认知层面对“肇事者”的行为和意图进行解释的, 但是却忽略了这样一个事实:道路攻击性驾驶事件往往是“一个巴掌拍不响”, 缺乏对“肇事者”潜在意图的关注, 也无法解释简单的道路冲突事件是如何一步步升级为严重的攻击性冲突。归因理论另一个不足是, 驾驶员并不总是将意图转变为行为。例如, Wickens等(2011)的研究发现, 愤怒情绪能够解释攻击意图36%的变异, 但是只能解释攻击行为9%的变异。也就是说, 驾驶员不会总是将意图转变为行为, 驾驶愤怒、驾驶攻击性意图和驾驶攻击性行为之间, 还隐藏着其他变量的作用。

3.4 一般攻击性模型

以上理论模型均强调某种因素对攻击性驾驶行为的决定性作用, Anderson和Bushman (2002)对以往的理论进行了综合, 提出了一般攻击模型理论(the general aggression model, GAM)。该理论认为个人的社会行为反应受到个人因素(人格和生理素质)和情境因素(攻击性线索、挑衅、挫折等攻击诱发因素)的交互影响。这两大因素被称为输入变量, 决定了个体当前内部的认知(敌意、图式)、情绪和唤醒状态, 这三种状态相互作用, 彼此激活, 共同引导评估和决策过程。评估过程可以分为即刻评估和重新评估, 即刻评估是一种快速的、自动化地评价, 引导冲动行为; 重新评估过程受意识控制, 深思熟虑之后引导行为。深思熟虑对于个体找到满意方案固然重要, 但是, 理性行为方案需要在问题空间中详细地搜索行为反应, 更加耗费认知资源, 因此并不令人满意。这并不意味着理性思考后, 个体就会选择非攻击性反应, 攻击性反应也可能是深思熟虑后的结果。Anderson和Bushman的模型具有循环性, 模型中任何社会行为的结果都被视为后续社会互动行为的输入变量。“肇事者” (原始攻击者)的攻击性行为会激发“受害者”的敌对反应, 敌对反应又进一步激发“肇事者”的攻击性行为, 从而使冲突升级。

如果要用一般攻击模型解释攻击性驾驶行为, 必须补充两个要点:引入诱发驾驶员敌意认知的特定道路事件(例如, 受阻情境); 提供驾驶员攻击性行为的操作性定义、分类和不同功能(例如, 工具性攻击和敌意性攻击)。而这两点问题, 恰恰可以结合“挫折-攻击”理论加以解决。

4 综合模型

Soole等(2011)将Shinar的“挫折-攻击”模型与一般攻击性模型相结合, 形成综合模型。首先, 保留了这两个模型共有的个人因素和情境因素作为核心变量, 并借鉴了“挫折-攻击”模型的观点, 认为驾驶员行驶受阻是攻击性行为产生的必要条件, 攻击性行为是驾驶员解决行驶受阻的一种行为方案或表达不满的发泄方式。因此, 增加了公路初始事件作为综合模型的起点变量(例如, 一位驾驶员被低速行驶的车阻碍道路), 并指出受阻条件不是攻击性行为产生的充分条件:挫折并不一定会导致攻击性行为, 有些特殊的情境和人格因素会对攻击性行为表达产生抑制作用, 有些驾驶员可以以适应性方式, 通过疏导挫折或消极情绪, 而做出非攻击性行为反应。因此, 驾驶员对公路初始事件的知觉和评估受到个人因素(例如年龄、性别、长期目标、特质敌意、信念、态度)和内部状态(例如情绪、唤醒水平), 以及情境因素(例如交通拥堵水平、警察是否在场以及匿名程度等)的综合影响, 共同决定了驾驶员的行为选择范围以及决策过程。受此影响, 驾驶员可能采取非攻击性的反应, 也可能在非驾驶情境中采取替代性攻击反应(例如, 在其他地方将愤怒和挫折转移发泄)。沿袭Shinar的理论, 攻击性反应本质上具有工具性(行为意图在于移除障碍, 例如开闪光灯、不停地变道), 或者服务于非工具性功能(报复性行为)。

攻击性行为是否升级, 取决于其他道路使用者的反应。如果其他道路使用者以有效消除障碍的方式作出回应(例如让出道路), 攻击性驾驶行为的循环就会终止。然而, 如果其他道路使用者以不服从的方式或者以攻击性的方式对感知到的“肇事者” (最先挑起攻击性事件的驾驶员)做出反应, 可能会导致冲突升级(“肇事者”尾随慢车), 这又成为新的道路诱发事件(Shaw, 2016)。

综合模型能很好地解释如下四个问题:(1)情境因素和个人因素是如何对攻击性驾驶行为产生交互作用的?(2)何种公路事件类型具有激惹性, 以及普遍性程度如何?(3)信念类型和认知评估过程如何对驾驶员的攻击性行为产生影响?(4)当驾驶员对公路激惹事件作出回应, 他们的意图和目标是什么, 他们是为了攻击吗?

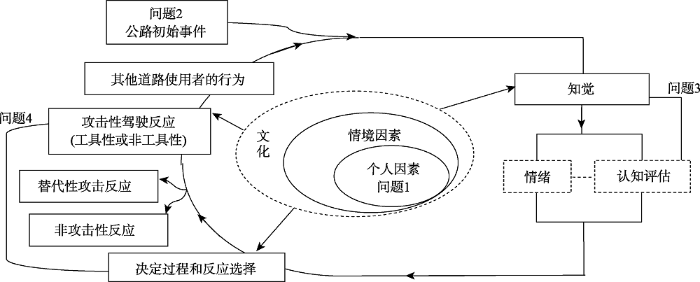

以上四个问题, 对应着综合模型的四部分结构:情境和个人因素的交互作用、诱发事件、认知评估以及行为反应意图。见图1 (虚线部分为作者新增变量)。

图1

图1

综合模型图(改编自Soole等, 2011)

4.1 情境和个人因素的交互作用

如前所述, 在综合模型提出之前, “挫折-攻击”理论、社会失调理论均探讨过情境因素和个人因素对攻击性驾驶行为的影响。一般攻击模型将这两个因素看做互相结合的输入变量, 强调二者的交互作用, 综合模型承袭了这一观点。

驾驶员遇到的道路情境往往是相似的, 但引发的驾驶行为却各不相同, 这与其个人因素(如性别、年龄、人格特质和道德品质等)密切相关。面对相同的情境, 个人因素对心理过程和行为反应起到调节作用, 影响着个人对情境的选择或者规避, 以及对当前情境的态度和感受, 并且这种影响具有跨时间和跨情境的一致性。换句话说, 驾驶情境中始终融入着驾驶员的个人色彩, 并预先“包含着个体的攻击性准备状态” (Anderson & Bushman, 2002)。

在性别方面, 男性极端暴力性质的攻击性驾驶行为比女性更多, 而非暴力性的攻击性驾驶行为没有显著的性别差异。在年龄方面, 年轻驾驶员更有可能采取攻击性驾驶行为 (Ben-Ari, Kaplan, Lotan, & Prato, 2016; Ge, Qu, Zhang, Zhao, & Zhang, 2015)。特别是那些年轻的、缺少责任心、对驾驶缺乏热情的驾驶员, 更容易对道路安全造成威胁, 因为他们更容易产生无聊感(Heslop, 2014)。

在众多人格特质中, 特质愤怒和特质攻击是被研究最广泛的两种特质(Bogdan, Măirean, & Havârneanu, 2016; Precht, Keinath, & Krems, 2017; Wang et al., 2018)。高特质愤怒的驾驶员, 更倾向于将其他驾驶员的“挑衅”行为理解为具有攻击意图, 由此增强其自身的愤怒和攻击性意图(Blankenship, Nesbit, & Murray, 2013)。高驾驶攻击性的驾驶员, 在兴奋寻求、风险卷入意图方面的得分也较高, 在安全态度方面的得分较低, 并会发生更多的交通违章事件(Rowden et al., 2016; Sani, Tabibi, Fadardi, & Stavrinos, 2017)。男性特质和驾驶员特质焦虑与驾驶员报复行为有显著正相关(Wickens, Wiesenthal, & Roseborough, 2015)。个人的宽恕品质与攻击性驾驶行为负相关(Bumgarner, Webb, & Dula, 2016; Kovácsová, Roáková, & Lajunen, 2014; Kovácsová, Lajunen, & Roáková, 2016)。

新近的研究表明, 道德推脱水平较高的驾驶员, 攻击性驾驶员水平也较高, 道德推脱是广泛存在于个体头脑中的一种特定道德认知倾向, 该认知倾向可以使得个体的内部道德标准失效, 并心安理得地做出不道德行为, 例如, 通过责任转移、责任分散、扭曲结果三个推脱机制, 掩盖或扭曲不道德行为的消极影响, 如将自己不道德的驾驶行为的责任归因于他人 (责任转移), 将个人过错的责任分散到驾驶外部情境中, 推脱自己的道德责任(Cleary, Lennon, & Swann, 2016; Wang, Yang, Yang, Wang, & Lei, 2017; Swann, Lennon, & Cleary, 2017)。Bailey, Lennon和Watson (2016)采用Forsyth (1980)编制的道德观点问卷, 根据理想主义和相对主义两个维度将驾驶员分成情境道德者(高理想主义/高相对主义)、绝对道德者(高理想主义/低相对主义)、主观利己者(低理想主义/高相对主义)和例外者(低理想主义/低相对主义)四类, 研究发现两类高理想主义者中(不愿给他人带来消极影响), 情境道德者产生驾驶愤怒情绪最高, 其次是绝对道德者, 但是这两类人展现出的攻击性驾驶行为倾向却最少。相反, 主观利己者感受到的驾驶愤怒最少, 但是展现的攻击性驾驶行为倾向却最多。高理想主义者们更愤怒, 是因为具有伤害性质或损害他人利益的行为不符合他们的道德立场, 同时, 这些驾驶员又强调他人的安全高于个人利益, 即使感受到了高水平的愤怒, 也会抑制自己的攻击性行为冲动。而针对中国驾驶员的研究发现, 持例外者道德立场的驾驶员攻击性水平最高, 研究者以文化差异解释这一现象, 相较于西方社会, 中国农业社会的历史延续更长, 血缘亲属纽带极为稳定和强大, 以道德规则代替法制规则, 成为一种强大的文化结构和心理力量, 这可能进一步加强了例外者通过暴力手段而不是法律手段维护社会公平的信念(Du, Shen, Chang, & Ma, 2018)。这充分说明, 驾驶愤怒不一定会导致攻击性驾驶行为, 而是受到文化情境与个人道德立场的交互影响。

4.2 诱发事件

在综合模型的四部分结构中, 深入分析诱发事件的性质, 是正确理解后续认知评估和情绪激活过程的基础。研究发现最让驾驶员感到恼火的情境包括被后车紧跟, 被抢道, 被逼停以及在超车道被一个开慢车的驾驶员挡道(Britt & Garrity, 2006; Wickens, Wiesenthal, Hall, & Roseborough, 2013)。Wickens等(2011)通过日记回溯法得到相似的结果, 愤怒诱发情境包括被抢道, 侧面碰撞, 被紧跟, 被龟速行驶的车辆挡道, 闯红灯或忽视让行标志, 阻挡并道或变道等, 其中被试报告最频繁的消极驾驶事件为被抢道或者险些被侧碰。为什么以上这些消极驾驶事件让驾驶员感到恼火, 这些事件被驾驶员视为挑衅的根本原因是什么?一种可能的假设是, 消极驾驶行为(例如, 抢道)侵犯了他人的安全制动距离, 造成了危险情境, 这种威胁引发恐惧(高度生理唤醒), 并转变为愤怒(Soole et al., 2011)。但是, Shaw (2016)通过日记回溯法和问卷调查法, 作出了另一种解释, 研究结果表明:驾驶员认为消极驾驶事件具有挑衅性质, 是因为此类事件往往是粗鲁和不礼貌的, 完全出于自私的意图, 不顾及其他驾驶员的需要, 对自己的行为给他人造成的负面影响欠缺考虑, 而不仅仅是有危险的。与危险行为相比, 缺乏“驾驶礼仪”更让人生气。

4.3 认知循环过程对攻击性驾驶行为的影响

4.3.1 驾驶文化对消极信念影响的认知循环过程

在综合模型提出之前, 归因理论已经明确指出, 敌意性归因、责备性归因以及内部可控有意性归因是促发攻击性驾驶行为的直接认知因素(Britt & Garrity, 2006; Hennessy, Jakubowski, & Leo, 2016; Wickens et al., 2011)。但是, 在模糊性的公路情境(驾驶员被超车后, 稍微提速行驶)中, 是什么因素促使了某些特定驾驶员(例如高特质攻击性)更容易产生敌意性归因倾向, 归因理论并没有做出详细解释。在社会认知过程中, 社会知觉是由图式引导的, 图式包括信念、态度、期望和感知到的标准及观念等, 这些因素与攻击性驾驶行为有一定相关性(Efrat & Shoham, 2013; Rowe et al., 2016), 然而, 很少有人研究攻击性驾驶员的信念和态度是如何对归因、社会知觉及社会情绪产生影响的(Efrat & Shoham, 2013)。

Yagil (2001)认为, 驾驶员与其他驾驶员互动过程中, 会逐渐形成一种“其他驾驶员”的群体印象, 这一群体印象包含了代表特定群体的特质和行为模板, 进而影响对这些群体行为的解释, 情境想象测验证明了这一点, 当驾驶员对其他驾驶员持有较多的消极看法时, 便会产生消极的归因倾向, 进而催生攻击性行为。Yagil进一步认为, 驾驶员的信念会受到驾驶文化的影响。Lonero (2007)将驾驶文化定义述为“驾驶员在社会中, 通过观察其他人所学到的普遍做法, 期望和非正式规则”。与这一观点一致, Yagil认为当驾驶文化趋向于具有攻击性, 驾驶员可能会更倾向于对其他驾驶员的行为做出消极的、充满敌意的归因。Lonero认为, 驾驶文化在不同地区, 国家之间都有所差异。Sinclair (2013)探索并比较了南非与瑞典的年轻驾驶员的态度和信念。Sinclair指出, 南非是一个高腐败程度、高犯罪率和高人际暴力的国家, 同时也是有着较高道路死亡率和高水平攻击性行为的国家。相比之下, 瑞典是世界上道路死亡人数最低的国家之一, 被公认为是和谐社会, 公民们信赖政府。Sinclair认为, 每个国家的社会文化和社会态度会在其驾驶员身上体现出来。正如预期的那样, 研究结果表明, 每个国家都有明显不同的驾驶文化:南非驾驶员对其他驾驶员持有更多的消极看法, 只有24%的南非驾驶员认为其他驾驶员服从并遵守道路规则, 并把他们形容为攻击性的、急躁的和不专心的。相比之下, 77%的瑞典驾驶员认为其他驾驶员服从并遵守道路规则, 并将驾驶员描述为宽容的、安全的和专注的。有趣的是, 南非样本中有99%的驾驶员将自己评为“极好的”或“优秀的”, 而瑞典只有65%。中国文化背景中的驾驶员常常采用缓和思维策略来平息情绪, 而不是通过攻击性驾驶行为来给自己制造更多的麻烦(Yan et al., 2016)。

Shaw (2016)根据Yagil和Sinclair的研究结果, 对综合模型中的认知过程进行了深度剖析, 强调了态度和信念对行为的重要性, 提出了认知循环过程中的“自我实现预言”效应:驾驶员在道路中遇到诱发事件时, 他们已有的人际信念会影响他们对目标驾驶员行为的评估, 增加其对其他驾驶员不良行为的认知倾向, 消极信念成为一种自我实现的预言, 导致其对其他驾驶员的鲁莽行为做出攻击性回应, 如果遭到报复, 或敌对驾驶员继续以不文明驾驶行为回应, 那么攻击性驾驶行为便逐步升级。

由此可见, 无论在何种驾驶情境中, 驾驶员的信念不可避免地会受到其自身文化潜移默化的影响, 不良驾驶文化将对驾驶员消极信念的形成起到助推作用, 在消极驾驶信念的影响下, 驾驶员人际信任遭到瓦解, 并迁移到后续公路初始事件的社会知觉过程, 形成敌意认知偏向, 产生消极情绪体验和攻击性反应倾向, 这种“自我实现预言”, 将最终固化驾驶员对其他道路使用者的负面印象, 持续恶性循环。因此, 在综合循环模型中, 应加入文化变量(见图1虚线部分), 同时, 由于交通文化是所有驾驶员的技能、态度和行为, 车辆和基础设施有影响的因素总和, 所以在图中, 文化因素包容了驾驶情境和个人因素, 并影响驾驶员对道路诱发事件的知觉、道路其他使用者行为的意图等, 并通过认知评估和情绪体验影响驾驶员行为的分配、控制和可能的行为反应。对这一问题的探讨, 能帮助我们从深层意义上解释攻击性驾驶行为产生的文化根源。

4.3.2 驾驶员人际信念的维度

Shaw通过访谈法和问卷调查法, 经探索性因素分析, 总结了对攻击性驾驶行为影响最大的五类驾驶员人际信念, 其中有四类信念为消极信念, 对攻击性驾驶起激发作用, 包括:不良驾驶礼仪的消极反应倾向(negative reactions to poor etiquette)、不良驾驶行为标准(poor driving standards)、惩罚不良驾驶行为信念(thoughts about reprimanding poor driving)、对其他驾驶员的消极刻板印象(negative stereotypes about other drivers); 还有一类称为带头榜样信念(leading by example), 是一种积极信念, 对攻击性驾驶起抑制作用。

不良驾驶礼仪消极反应倾向, 是指驾驶员认为其他驾驶员应该表现出适当的驾驶礼仪(文明的、礼貌的驾驶行为, 包括对其他道路使用者的尊重和体谅, 对不良驾驶行为的宽容), 对于不良礼仪有厌恶和愤怒反应倾向(Lennon & King, 2015)。

不良驾驶行为, 是指不遵守道路规则, 自大粗鲁及粗心驾驶等行为, 不良驾驶行为标准是指, 驾驶员对驾驶环境中遇到的其他道路使用者不良驾驶行为的预期或假定, 如果驾驶员把不良驾驶行为看做是社会通用的一般驾驶标准, 那么便会产生认知偏差和注意定势, 个人倾向于在驾驶环境中寻找、注意负面信息, 证实他们所相信的负面标准和期望(Nickerson, 1998)。

惩罚不良驾驶行为信念, 是指驾驶员认为其他驾驶员的不良驾驶行为应该受到谴责, 因此他们有时会做出相应的攻击性驾驶行为反应, 并认为这样做是“给他们一个教训”。

对其他驾驶员的消极刻板印象, 是指驾驶员对道路事件的评估受到对某些特定车辆类型以及特定驾驶员消极刻板印象的影响, 如开越野车的驾驶员总是被认为是粗鲁的, 他们总是凭借自己的高大车身来恐吓其他车辆, 女性驾驶员和新手驾驶员都是技术欠佳, 缺少道路礼仪, 因此这类车辆更容易引起驾驶员的愤怒和攻击性回应。

带头榜样信念是指驾驶员总是认为自己的驾驶行为是遵守规则的、为他人考虑的、文明且有礼貌的。Shaw研究表明, 具有带头榜样信念的人对于道路诱发事件有较少的愤怒发泄情绪。

前四种消极的信念具有的共同特征是:都表现了驾驶员对适当驾驶礼仪的期望和信念。例如, 抢道被认为是违反了驾驶礼仪, 因为驾驶员出于自私的意图来让自己的车前进, 而延缓了其他驾驶员的通行。同样的, 龟速前进也被认为是违反了驾驶礼仪, 他们并没有考虑到自己的行为可能会对其他驾驶员造成的影响。

4.3.3 攻击性图式的自动化行为激活效应假设

一直以来, 归因理论强调归因方式对责任推断、愤怒情绪和驾驶攻击行为具有递进式激活作用, 内部稳定性归因被研究者认为是一种最具有敌意性的归因模式, 例如, Lennon, Watson, Arlidge和Fraine (2011)认为, 当驾驶员将消极的道路事件(例如被抢道)归因于违规驾驶员的不良性格和糟糕技术, 便会认为肇事驾驶员应对挑衅事件负责, 对其进行攻击是合理的。Shaw的研究表明, 进行内部稳定归因的驾驶员, 的确报告了更强烈消极情绪, 但是, 与归因理论的假设相反, 他们报告了非攻击性反应意图, 更倾向于用自我发泄的方式排解挫折感和愤怒感。

Shaw和Du同时发现, 那些报告了攻击性反应意图的驾驶员, 却没有明显的归因倾向和消极情绪体验。这一结果完全出乎研究者的预期, 无法用归因理论进行解释, Shaw认为, 这可能是因为自我中心主义的个体在威胁性情境中, 会通过攻击性行为来进行自我防御。自我中心主义的极端发展形式是自恋特质, 即自我膨胀和夸大自我(Dewall & Bushman, 2011; Konrath, Bushman, & Campbell, 2006; Hennessy, 2016)。自恋特质个体对环境中的威胁线索更加敏感, 更加倾向于对环境进行威胁性评估(Bushman, Steffgen, Kerwin, Whitlock, & Weisenberger, 2018; Demir, Demir, & Özkan, 2016; Przepiorka, Blachnio, & Wiesenthal, 2014)。

根据这些实证研究结果, 有充分的理由可以考察这样一种假设:自恋特质的驾驶员, 在驾驶经验积累过程中, 固化了攻击性图式, 形成高度自动化的攻击性行为反应模式, 从而绕过消极情绪激活, 而直接诱发攻击反应。这也说明, 人格特质和道路情境可能会对攻击性行为产生自动化激活效应, 这种假设可以作为对综合模型进一步扩展的切入点。如果可以通过实证研究加以证实, 那将意味着, 综合模型一直强调的攻击性驾驶行为判断标准之三—消极情绪伴随假设将被证伪。而在综合模型原有的循环图中, 情绪与认知评估被视作同步激活过程, 因此被置于同一模块内, 基于以上最新的实证研究证据, 有理由将情绪与认知评估分别置于不同的模块并行连接(见图1虚线部分), 留待研究者探讨空间, 以验证是否存在攻击性图式的自动化行为激活效应。

4.4 行为反应意图

综合模型以周期循环模式来解释攻击性驾驶行为, 行为反应意图是联结认知、情绪评估和道路事件的重要一环。Shaw的研究表明, 大部分驾驶员都会对挑衅事件作出反应, 而不是无视它们。驾驶员对诱发事件可采取两类反应:攻击性驾驶行为或非攻击性驾驶行为。Shinar (1998)将攻击性驾驶行为又分为工具性攻击行为和非工具性攻击行为(敌意性攻击行为)。

工具性驾驶攻击是为了帮助受阻的驾驶员向前行驶, 规避道路障碍, 例如, Emo, Matthews和Funke (2016)的研究表明, 有些驾驶员为了尽快脱离拥堵环境, 会在有超车机会时采取极具风险性的侵犯性驾驶策略, 对立策略俨然成为这类驾驶员应对拥堵的行为习惯, 而非简单的情绪发泄。当被其他驾驶员侵犯时, 驾驶员会采取大声鸣笛、粗鲁的手势、紧紧尾随前车等攻击性反应, 是为给对方驾驶员传递信息:你的驾驶行为不符合驾驶礼仪, 是令人厌恶的。即这样做是给对方驾驶员一个教训, 促使他们修正或改善驾驶能力(Shaw, Lennon, & Watson, 2014)。

工具性攻击是驾驶员为了达到自己的某种目的一种有计划伤害行为, 然而为了超车而紧跟前车的驾驶员是否有伤害性意图并伴随消极情绪, 这个问题是值得商榷的。例如, 驾驶员可能仅仅是为了节约时间这个单纯目的而缩短跟车距离, 即使这么做会让前车驾驶员感到不舒服, 但是后车驾驶员并没有伤害他人的动机, 也没有愤怒或挫折感受。那么这种工具性行为还是否可以界定为攻击性行为呢?这种质疑再次对综合模型的驾驶攻击性行为界定标准提出挑战。对此问题, 我们也许可以提出这种假设:驾驶员的意图和情绪会随事件发展而改变, 例如一开始, 驾驶员紧跟前车, 可能仅仅只是为了逼迫前车让路, 但是如果前车驾驶员继续阻碍其前行, 那么攻击性意图和消极情绪便会由此产生。接下来的问题便是, 哪些因素会影响驾驶员伤害意图和消极情绪的产生?只有通过实证研究系统地解决这些问题以后, 才能对综合模型进行检验和修改。

敌意性驾驶攻击具有非工具性, 是指驾驶员感到对方的不良驾驶行为威胁到了自己, 便采取同样的攻击性方式回应, 如碰撞、粗鲁手势等, 意图伤害对方驾驶员, 使对方感到沮丧, 害怕和不便, 却并没有真正解决问题。Shaw的研究表明, 对抗或敌意意图较多的驾驶员, 报告的消极情绪更少。这一结果和社会排斥研究非常类似, 被他人排斥的个体会在缺乏消极情绪的前提下, 而迅速激发攻击回应(Twenge, Baumeister, Tice, & Stucke, 2001)。同样, 当驾驶员对自己的驾驶技能非常自信, 认为自己优于对方驾驶员, 会更在意他人的批评, 更倾向于将诱发事件评估为一种自我威胁事件, 绕过情绪反应而直接诱发攻击行为反应, 维护自我形象。这说明, 驾驶员攻击性图式对攻击性行为的激发过程中, 有意识的认知加工参与较少。

非攻击性驾驶行为, 只是为了发泄挫败感和不满情绪, 而并没有对目标驾驶员造成伤害。Shaw的研究表明, 内部稳定性归因方式与消极情绪显著正相关, 但是这种有意识的认知加工倾向于激活非攻击性的反应方式来发泄情绪。有趣的是, 发泄的意图与带头榜样信念负相关, 即那些具有带头榜样信念的驾驶员对于道路挑衅事件很少进行发泄。

5 展望

5.1 攻击性驾驶行为研究手段客观性难题的解决途径

目前大多数攻击性驾驶行为研究, 都只能采用问卷调查法或情境想象实验, 严重依赖于被试的情景记忆能力和社会赞许性倾向, 无法保证研究的效度。这主要是由于攻击性驾驶行为本身是一种在特殊驾驶情境中产生的反社会行为, 很难在实验室中进行模拟或复现。

单靠问卷调查法和情境想象实验, 远不能解决综合模型新提出的理论问题, 需要对驾驶员的认知评估过程和情绪反应进行实时或事件相关性测量。为解决这一难题, 可以考虑三种途径。一种方法是进行驾驶模拟器实验, 通过设计道路拥堵或被虚拟车辆侵犯的仿真情境, 来诱发驾驶员的愤怒情绪, 此时便可结合生理多导仪或脑电测量技术, 考察认知评估对唤醒情绪的神经机制。同时, 也可由驾驶模拟器获取驾驶绩效指标(车速、方向盘转角、车道位置变异性), 来获取驾驶员的外显攻击性反应。这种方法还可以与人格测量相结合, 在实验前后, 对被试的人格特质和态度信念进行筛选和分组, 从而考察综合模型关于人格特质和道路情境交互作用的理论假设。

但是, 驾驶模拟器研究毕竟是在虚拟环境中进行的, 生态效度有待商榷, 另一种可行办法是搜集自然场景下的驾驶行为数据。例如, 通过车载摄像机拍摄驾驶员在自然驾驶场景下的愤怒状态和平静状态视频, 并对其违规、攻击、操作失误及对方车辆反应等行为进行编码和分析对比, 从而对综合模型的道路冲突升级过程和认知循环过程进行证明。Precht等人(2017)使用这种方法进行了初步尝试, 虽然获取到真实驾驶场景中驾驶员的“本色”表现, 但是由于攻击性驾驶行为的发生具有很大的偶发性, 往往需要拍摄海量视频, 才能最终搜集到几分钟的可用材料, 大大限制了被试数量。同时, 由于愤怒诱发事件各不相同, 混淆进各种无关变量, 增加生态效度的同时, 降低了实验的内部效度。

因此, 未来研究者需要考虑第三种途径, 是将内隐联想测验、人格测验、情绪的生理测量与驾驶模拟器或自然场景实验相结合。由于攻击性驾驶行为属于一种反社会行为, 在实验环境中, 极有可能被被试的社会赞许性意图所掩盖, 而内隐联想测验不但能避免自我报告中被试自我掩饰的影响, 还可以灵活运用不同的客体概念和属性概念, 揭示攻击性的无意识层面、内隐态度和图式。同时, 内隐联想测验与人格测验和虚拟仿真/现场实验的结合(例如, 以内隐联想测验测量得到的驾驶员内隐攻击性意图为自变量, 以人格特质或道德信念为调节变量, 以生理指标和驾驶员攻击性表现为因变量, 建立数据拟合模型), 将大幅增加测量手段的客观性, 更好地对攻击性驾驶行为的理论假设进行验证。

5.2 综合模型的理论深化和拓展

如果攻击性驾驶行为研究手段即时性、客观性和有效性的难题得以解决或部分解决, 将激发对驾驶员攻击性本质的新探索。与以往模型相比, 综合模型更加系统化。在其提出之前, 社会失调理论强调影响攻击性驾驶行为的人格因素, “挫折-攻击”理论强调情境因素, 归因理论强调社会认知因素。综合模型借鉴了一般攻击性模型的系统化思想, 将以往理论中的关键变量进行系统综合, 结合驾驶情境, 提出个人因素与情境因素对心理过程具有交互作用, 阐明了认知评估、情绪唤醒和行为反应的影响机制。其最大的创新之处在于其循环论思想, 认为攻击性驾驶行为始于一个最初的公路事件, “受害者”经过一系列认知活动, 最终做出报复行为, 并直接决定了“肇事者”后续的反应, 导致冲突升级, 并带来新的道路事件, 重复循环。因此, 该模型能很好解释在道路冲突中, 驾驶员的攻击性持续升级的原因, 以及为什么在道路攻击性驾驶行为事件中, “肇事者”和“受害者”的角色模糊不清, 这有助于更好地确定攻击性驾驶行为对交通事故和道路安全的影响, 对攻击性驾驶行为的对策研究具有重要应用价值。但是, 限于研究方法的问题, 综合模型自身还有一些问题亟待解答。例如, 攻击性驾驶行为的界定标准如何确定?驾驶情境和哪些个人因素会产生交互作用?文化如何对驾驶员信念、认知评估、情绪体验及行为反应产生影响?是否存在攻击性图式的自动化行为激活效应?在整个道路冲突事件中, 驾驶员的攻击意图如何变化?只有通过更加客观化的手段, 才能深入探明驾驶员攻击性的内在机制。

同时, 综合模型的人格及自我调控视角还有待扩展。首先, 与大多数攻击性驾驶行为的理论模型相似, 该模型过多地强调消极的人格特质因素(如特质愤怒和特质攻击)和敌意信念对攻击性驾驶行为的影响, 但如果要建立有效的攻击性行为综合预测模型, 应同时确定能够抑制驾驶员攻击性行为的影响因素有哪些。目前这类研究非常稀少。未来研究者可以将目光着眼于积极的人格特质和积极信念研究, 例如, 可以进一步开展关于个人的理想主义信念、公平公正信念、道德认同感对攻击性驾驶行为和愤怒反思抑制作用的影响研究。研究者还可以考虑驾驶员对未来行为后果斟酌的倾向性、安全态度倾向性、亲社会倾向的影响作用, 这些积极的人格特质和信念是预防和干预攻击性驾驶行为的重要变量, 势必将成为未来攻击性驾驶行为研究的热点问题。

第二, 以自我调控的视角来审视综合模型, 是攻击性驾驶行为研究的新方向。综合模型的核心思想是, 驾驶员受攻击诱发情境和自身不良人格特质的交互影响, 并在认知系统中自动化地激发攻击图式, 由此确定攻击性意图, 做出攻击行为反应, 这又激发了他人的攻击行为反馈, 形成恶性循环, 进一步增强了消极信念。但是, 这种决定论思想忽视了驾驶员的自我调控机制, 没有看到现实生活中个体意志的主观能动性。驾驶行为和人类大多数行为一样, 是一种目标导向行为, 个体的主观努力控制过程决定着驾驶策略的选择和执行(Craciun, Shin, & Zhang, 2017)。未来研究者应着眼于这样的理论假设:如果个体的最高驾驶行为目的是确保行车安全, 那么即使身处攻击情境, 也会努力抑制愤怒, 独善其身; 相反, 如果个体的最高驾驶行为目的是确保行车效率或彰显驾驶技能, 更可能因一时冲动, 而采取攻击性驾驶行为。

5.3 综合模型的应用前景

如果能够进一步深化和拓展综合模型的, 探明驾驶员攻击性的内在心理机制和影响因素, 将为寻求对驾驶员暴力行为的预防和干预提供科学依据。首先, 可以对驾驶员进行再教育, 提高其道路人际沟通技能。在面对面的交流中, 当接收到对方的歉意, 愤怒通常会冷却下来。但是在驾驶情境下, 车辆封闭性和匿名性直接导致驾驶员在判断其他道路使用者的行为意图时, 产生“归因偏差” (Haglund & Åberg, 2000), 进而产生消极的互动体、态度和情绪。这主要是因为在驾驶环境中, 试图表达愤怒和接受反馈或道歉的途径有限:有些抑制他人愤怒的社会提示, 如语音和面部表情, 除非过分夸大, 否则在封闭性的高速驾驶情境中, 不可能及时传递给其他驾驶员。这就需要驾驶员掌握良好的车辆信号(车语)使用技能, 将意图及时通知给其他道路使用者。探索道路人际互动对道路敌意的消除作用, 将是未来攻击性驾驶行为研究的有趣方向。现有研究表明, 车语可以改变驾驶员互动的主观评价以及对其他驾驶员的态度和情绪反应(Ba, Zhang, Reimer, Yang, & Salvendy, 2015; Ji et al., 2015)。因此, 未来研究者可以探索不同驾驶经验和性别的驾驶员, 在道路互动过程中的信息沟通技能, 并由此开发车辆之间即时性信息通讯系统, 将具有广阔的应用前景。

第二, 可调控也意味着可改善, 对自我调控机制的深入研究将成为攻击性驾驶行为干预方案的重要理论基础。例如, 研究者可以尝试探索自尊、自责、预期后悔、责任推脱等因素对攻击性驾驶行为是否具有中介作用, 教育工作者、执法人员和心理咨询师也可以借助于加强个体的自我调控机制, 来提高攻击性驾驶行为的干预效果。

总之, 综合模型为我们全面系统地了解驾驶员攻击性驾驶行为的心理机制及影响因素, 提供了一个综合框架, 这有助于制定新手驾驶员、特别是青少年驾驶员培训计划, 帮助驾驶员更有效地改正他们的消极信念及处理愤怒情绪, 为预防和干预攻击性驾驶行为提供针对性的指导策略。

参考文献

《道路交通运输安全发展报告( 2017)》

2015年中国道路交通安全蓝皮书

《2015年中国道路交通安*蓝皮书》共四篇七章。*一篇为发展历程篇,回顾了新中国成立以来,特别是近十年来我国道路交通安*发展历程,分析了目前我国道路交通安*面临的形势、挑战与机遇;第二篇为现状热点篇,总结了2014年我国道路交通安*形势,剖析了2014~2015年道路交通安*方面的热点问题;第三篇为措施研究篇,列举了2014年我国改善道路交通安*的主要举措,介绍了道路交通安*研究的进展,并介绍了瑞典道路交通安*“零伤亡愿景”;第四篇为新技术研究篇,介绍了当前较为先进的道路交通安*新技术。另外,《2015年中国道路交通安*蓝皮书》还编录了2014年道路交通安*十大新闻、2014年一次死亡10人以上的重大道路交通事故、网络舆情精选、国际道路交通安*数据。

Aggressive driving: Research update.

Human aggression

The effect of communicational signals on drivers' subjective appraisal and visual attention during interactive driving scenarios

DOI:10.1080/0144929X.2015.1056547

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Communicational signals (e.g. lights and horns) are imperative for on-road interaction between drivers. The aim of the present study was to explore how these signals affect drivers' subjective appraisal and visual attention, and how drivers decode the signals from other vehicles within a variety of interactive contexts. Twenty-five male participants (20 valid samples, ranging from 21 to 29 years of age) were recruited to watch film clips of pre-designed interactive scenarios involving common vehicle signals in a full-view simulator (i.e. including road view and mirror views). Participants' attitudes towards the interacting vehicle's behaviours, emotional responses, fixation metrics, and decoded meanings were recorded and analysed. The majority of tested signals, with the exception of the horn used in the behind vehicles, significantly improved drivers' attitudes and pleasure. All signals significantly increased emotional arousal, as well as the total fixation time and mean fixation duration on the interacting vehicle. When the interacting vehicle was visible in mirrors, the signal usage significantly increased the fixation frequency towards it. Meanwhile, a significant decrease in total fixation time and mean fixation duration on the road was reported. The results also demonstrated that the decoded signal contained several meanings simultaneously depending on both the signal type and its interactive context. This study quantified the communication process via vehicular signals under typical situations involving other vehicles, and also suggested new ideas on how to establish more advanced communication between drivers.

Getting mad may not mean getting even: The influence of drivers’ ethical ideologies on driving anger and related behaviour

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2015.11.004

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The current study explored the influence of moral values (measured by ethical ideology) on self-reported driving anger and aggressive driving responses. A convenience sample of drivers aged 17 73years (n=280) in Queensland, Australia, completed a self-report survey. Measures included sensation seeking, trait aggression, driving anger, endorsement of aggressive driving responses and ethical ideology (Ethical Position Questionnaire, EPQ). Scores on the two underlying dimensions of the EPQ idealism (highI/lowI) and relativism (highR/lowR) were used to categorise drivers into four ideological groups: Situationists (highI/highR); Absolutists (highI/lowR); Subjectivists (lowI/highR); and Exceptionists (lowI/lowR). Mean aggressive driving scores suggested that exceptionists were significantly more likely to endorse aggressive responses. After accounting for demographic variables, sensation seeking and driving anger, ethical ideological category added significantly, though modestly to the prediction of aggressive driving responses. Patterns in results suggest that those drivers in ideological groups characterised by greater concern to avoid affecting others negatively (i.e. highI, Situationists, Absolutists) may be less likely to endorse aggressive driving responses, even when angry. In contrast, Subjectivists (lowI, HighR), reported the lowest levels of driving anger yet were significantly more likely to endorse aggressive responses. This provides further insight into why high levels of driving anger may not always translate into more aggressive driving.

The combined contribution of personality, family traits, and reckless driving intentions to young men’s risky driving: What role does anger play?

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2015.10.025

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The study investigated the relation between the risky driving behavior of young male drivers and their personality traits, familial attitudes and conduct in respect to road safety, intentions to drive recklessly, and driving anger. In-vehicle data recorders were used to measure the actual driving of 163 young male drivers, who also completed self-report instruments tapping traits and perceptions. Personality traits were assessed near in time to receipt of the driving license, and actual risky driving and driving-related variables were measured 9 12months after licensure to examine relatively stable driving behavior and attitudes. Findings indicate that (a) young male drivers personality traits and tendencies play a major role in predicting risky behavior; (b) intentions to drive recklessly are translated into actual behavior; and (c) the parental role is extremely relevant and counteracts risky tendencies. Moreover, the results suggest that although trait anger and driving anger both contribute to risky driving, they represent different aspects of anger. Thus, for safety interventions to be effective, they must not only teach drivers how to cope with anger-provoking driving situations, but also address underlying personality traits and environmental factors.

Driving anger and metacognition: The role of thought confidence on anger and aggressive driving intentions

DOI:10.1002/ab.21484

URL

PMID:23592602

[本文引用: 1]

The present studies examined the self-validating role of anger within provoking driving situations, using a scenario method. Specifically, we predicted that one reason for why individuals higher (rather than lower) in trait driving anger are more likely to aggress when provoked is because these individuals are more confident in their thoughts resulting from the provocation. Higher thought confidence, in turn, may influence the amount of anger experienced and the extent to which the anger translates into aggressive behavior. Study 1 found that participants higher in driving anger were more confident in their thoughts in a provoking situation and their thought confidence mediated the effect of trait driving anger on anger in response to the provocation. Using a manipulation of consistency, Study 2 found that thought confidence mediated the influence of anger on aggressive driving intentions, but only for individuals higher in driving anger. The current research adds to the growing work examining a new mechanism by which emotion (e.g., anger) can affect behavior. Aggr. Behav. 39:323 334, 2013. 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

A meta-analysis of the association between anger and aggressive driving

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2016.05.009

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The aim of this paper was to evaluate the relationship between anger (trait and driving anger) and aggressive driving. In order to test these relationships, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on anger and aggressive driving. We identified 51 eligible studies that we included in this meta-analysis. Based on previous literature, we hypothesised that: (1) there is a positive relationship between anger and aggressive driving; (2) the relationship between anger and aggressive driving behaviour differs based on whether anger is trait-based or traffic context-specific; (3) this relationship also varies depending on the type of aggressive driving; and (4) the relationship between specific anger type and aggressive driving vary according to gender, age, region where the studies were conducted and driving experience. The quantitative analysis was conducted using meta-analytic techniques. Results confirmed the fact that there is a positive relationship between anger and aggressive driving behaviour, the relationship being stronger for trait anger. Moreover, the relationship between anger and aggressive driving depends on different forms of aggressive driving, gender, age, driving experience, and the region where studies were conducted. The theoretical and practical implications of these results are discussed.

Attributions and personality as predictors of the road rage response

DOI:10.1348/014466605X41355

URL

PMID:16573877

[本文引用: 2]

Abstract This study examined the ability of attributions and personality traits to predict the emotional and behavioural components of the road rage response. Participants recalled a recent time when they experienced three different anger-provoking events when driving. They then rated their behaviours and emotions during the event, and their attributions for why the event occurred. Participants also completed a battery of personality questionnaires designed to predict their responses to the situations. Attributing causality for the anger-arousing event to a stable factor in the offending driver was uniquely related to aggressive behaviour and anger in all three situations. Hostile and blame attributions predicted aggressive behaviour and anger in different situations. In addition to dispositional measures of aggressiveness and anger predicting aggressive behaviour and anger in each of the anger-provoking situations, other personality variables were also related to aspects of the road rage response (e.g. conscientiousness, agreeableness, narcissism, and extraversion). Attributions and personality traits accounted for unique variance in the outcomes, and there were only sporadic effects of attributions partially mediating the relationships between personality variables and responses to the anger-provoking situations. Therefore, it is unlikely that the relationships between personality traits and responses to anger-provoking situations are completely mediated by attributional processing.

Forgiveness and adverse driving outcomes within the past five years: Driving anger, driving anger expression, and aggressive driving behaviors as mediators

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2016.07.017

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Purpose:In the United States, motor-vehicle crashes are the leading cause of death for individuals 18鈥24years of age. Multiple factors place young drivers at an increased risk including risky and aggressive driving behaviors. Aggressive driving has been shown to account for more than half of the driving fatalities in the United States. Driving anger is predictive of aggressive driving and adverse driving outcomes. Research outside the context of driving has demonstrated associations between multiple dimensions of forgiveness and anger, aggressive behaviors, and health outcomes. A very small body of research suggests a modest relationship between forgiveness and both driving anger and aggressive driving. The current study expands on previous research to examine the impact of multiple dimensions of forgiveness on adverse driving outcomes.Methods:Undergraduate students (N=446) completed, self-report measures of forgiveness, driving anger, driving anger expression, aggressive driving behaviors, and aversive driving outcomes.Results:Bivariate correlations indicated a significant negative relationship between each dimension of forgiveness and driving anger, driving anger expression, and aggressive driving. Forgiveness (of others and of uncontrollable situations) was found to have a significant indirect only effect on traffic violations through the mediators of driving anger and aggressive driving.Discussion: Current findings support and expand on previous research examining the association of forgiveness with adverse driving outcomes. Forgiveness of othersandforgiveness of uncontrollable situations, but not forgiveness of self, were shown to indirectly impact traffic violations/warnings, but not crashes, within the past five years through reduced driving-related anger, anger expression, and/or aggression. Implications, limitations, and future research are discussed.

“Don’t you know I own the road?” The link between narcissism and aggressive driving

Characteristics of perpetrators of serious violence on the roads

DOI:10.1080/13218711003739102

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This study examined data from convicted offenders in the Australian state of Victoria to examine whether the perpetrators of interpersonal violence differ between road and non-road contexts. A case ontrol methodology was used to compare data from 31 episodes of road violence with 31 episodes of violence against strangers that resulted in similar charges but which occurred in non-road contexts. Information regarding perpetrators was obtained from prosecution legal files. Psychiatric contact information was obtained from the Victorian public mental health database on both cases and controls. Although a sizeable proportion of incidents of road violence was perpetrated by persons who had not previously been criminally violent, this proportion was not significantly different from that found in the controls. The study provides support for causal models of road violence that emphasize individual traits rather than environmental factors and thus has implications for preventative strategies.

Should we be aiming to engage drivers more with others on-road? Driving moral disengagement and self-reported driving aggression

Safe driving communication: A regulatory focus perspective

DOI:10.1002/cb.1654

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract This research article examines the effects of self-regulation on adolescents' aggressive driving tendencies and their attitudes toward safe driving communication. Two experimental studies demonstrate that an individual's regulatory orientation is a good predictor of aggressive driving tendencies and that self-regulation plays a moderating role on the effects of safe driving messages on recipients' attitudes. Specifically, the findings reveal that promotion-oriented (vs. prevention-oriented) individuals are more likely to demonstrate aggressive driving tendencies. In addition, promotion-oriented individuals show more favorable attitudes toward gain-framed safe driving messages than loss-framed messages. Prevention-oriented individuals show the opposite pattern. Implications for theory and practice are discussed.

The exceptionists of Chinese roads: The effect of road situations and ethical positions on driver aggression.

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2018.07.008 URL [本文引用: 1]

A contextual model of driving anger: A meta-analysis

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2016.09.020

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Driver anger is an important individual difference variable that has been investigated extensively for understanding driving outcomes. The Driving Anger Expression Inventory (DAX i.e., physical, verbal, use of vehicle as an aggression tool, and adaptive/constructive practices) and the Driver Behavior Questionnaire (DBQ i.e., errors, lapses, and violations) are common outcome measures for investigating how people express their anger while driving. The current study aims to conduct a meta-analytic review of other individual differences (e.g., Big Five, narcissism, impulsiveness) and several outcome variables (i.e., DAX, DBQ) associated with driving anger, measured using the driving anger scale (DAS). It synthesized information from 48 studies using the meta-analytic approach in the scope of the Contextual Mediated Model (Lajunen, 1997; S mer, 2003). The results suggested that impulsiveness, normlessness, and narcissism have stronger associations with driving anger than the Big Five personality factors. In addition, driving anger had significant associations with both the types of anger expression (i.e., physical aggression, verbal aggression) and aberrant driver behavior factors (i.e., violations, errors). Specifically, the DAS had stronger associations with the driving anger expression (DAX) factors than with the aberrant driving behavior (DBQ) factors. Moreover, the relationship between the DAS and the violations factor of the DBQ was stronger than the relationship between the DAS and the other DBQ factors. The implications of the findings for both research and practice are discussed.

Social acceptance and rejection: The sweet and the bitter

DOI:10.1177/0963721411417545

[本文引用: 1]

ABSTRACT People have a fundamental need for positive and lasting relationships. In this article, we provide an overview of social psychological research on the topic of social acceptance and rejection. After defining these terms, we describe the need to belong and how it enabled early humans to fulfill their survival and reproductive goals. Next, we review research on the effects of social rejection on emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and biological responses. We also describe research on the neural correlates of social rejection. We offer a theoretical account to explain when and why social rejection produces desirable and undesirable outcomes. We then review evidence regarding how people cope with the pain of social rejection. We conclude by identifying factors associated with heightened and diminished responses to social rejection.

The theory of planned behavior, materialism, and aggressive driving

DOI:10.1016/j.aap.2013.06.023

URL

PMID:23911617

[本文引用: 1]

Aggressive driving is a growing problem worldwide. Previous research has provided us with some insights into the characteristics of drivers prone to aggressiveness on the road and into the external conditions triggering such behavior. Little is known, however, about the personality traits of aggressive drivers. The present study proposes planned behavior and materialism as predictors of aggressive driving behavior. Data was gathered using a questionnaire-based survey of 220 individuals from twelve large industrial organizations in Israel. Our hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling. Our results indicate that while planned behavior is a good predictor of the intention to behave aggressively, it has no impact on the tendency to behave aggressively. Materialism, however, was found to be a significant indicator of aggressive driving behavior. Our study is based on a self-reported survey, therefore might suffer from several issues concerning the willingness to answer truthfully. Furthermore, the sampling group might be seen as somewhat biased due to the relatively high income/education levels of the respondents. While both issues, aggressive driving and the theory of planned behavior, have been studied previously, the linkage between the two as well as the ability of materialism to predict aggressive behavior received little attention previously. The present study encompasses these constructs providing new insights into the linkage between them.

The slow and the furious: Anger, stress and risky passing in simulated traffic congestion

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2016.05.002

URL

[本文引用: 1]

112 college students participated in a study of simulated driving to investigate how trait driver aggression, state anger and coping predict risk-taking behaviors such as tailgating and frequency of passing. The simulation scenario, driving in slow traffic, elicited both anger and stress. However, consistent with the transactional model of driver stress, anger and distress were associated with different patterns of coping. Both anger and aggression were associated with dispositional confrontive coping. Drivers were afforded opportunities to pass other traffic, in risky circumstances. Dispositional coping factors, especially confrontive coping, predicted risk-taking behaviors, such as frequent passing and tailgating prior to the pass. However, trait aggression and anger did not predict risky behaviors. Confrontive drivers may have developed habitual behavioral styles that are expressed irrespective of current mood and coping strategy. The findings suggest that stress or anger management may be only a partial solution to dangerous driving in congested conditions. Further investigation of how drivers acquire confrontive behavioral styles is needed. The data also support multivariate approaches to selecting safe drivers in commercial and industrial contexts.

The use of a driving simulator to determine how time pressures impact driver aggressiveness

DOI:10.1016/j.aap.2017.08.017

URL

PMID:28865928

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Speeding greatly attributes to traffic safety with approximately a third of fatal crashes in the United States being speeding-related. Previous research has identified being late as a primary cause of speeding. In this driving simulator study, a virtual drive was constructed to evaluate how time pressures, or hurried driving, affected driver speed choice and driver behavior. In particular, acceleration profiles, gap acceptance, willingness to pass, and dilemma zone behavior were used, in addition to speed, as measures to evaluate whether being late increased risky and aggressive driving behaviors. Thirty-six drivers were recruited with an equal male/female split and a broad distribution of ages. Financial incentives and completion time goals calibrated from a control group were used to generate a Hurried and Very Hurried experimental group. As compared to the control group, Very Hurried drivers selected higher speeds, accelerated faster after red lights, accepted smaller gaps on left turns, were more likely to pass a slow vehicle, and were more likely to run a yellow light in a dilemma zone situation. These trends were statistically significant and were also evident with the Hurried group but a larger sample would be needed to show statistical significance. The findings from this study provide evidence that hurried drivers select higher speeds and exhibit riskier driving behaviors. These conclusive results have possible implications in areas such as transportation funding and commercial motor vehicle safety. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

A taxonomy of ethical ideologies

The effectiveness of a brief psychological intervention on court-referred and self-referred aggressive drivers

DOI:10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00100-0

URL

PMID:12457634

[本文引用: 1]

This study tested the efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral psychological intervention (CBT) targeting aggressive driving behaviors within both a court-referred ( N=20) and a self-referred community ( N=8) sample as compared to a symptom monitoring (SM) only control condition. Treatment outcome was assessed through the use of daily driving diaries, standard psychological tests, and a global rating of change scale. The CBT treatment condition improved more than the SM condition as assessed through the daily driving diaries. Although the court-referred and self-referred samples showed equivalent improvement on the driving diaries, the self-referred group improved more on measures of general anger. Standardized measures of driving anger, state anxiety and measures of general anger indicated significant change in the expected direction. Aggressive drivers who met criteria for Intermittent Explosive Disorder (IED) showed a trend to improve less than non-IED aggressive drivers. Treatment gains were maintained at the 2-month follow-up point.

Psychometric adaptation of the driving anger expression inventory in a Chinese sample

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2015.07.008

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The purpose of this study was to assess the psychometric properties and the factorial structure of the Driving Anger Expression Inventory (DAX) in a Chinese sample. We also explored the relationships among driving anger expression, general anger expression, and driving outcomes. Three hundred and fifty-eight drivers completed the Chinese version of the DAX, the Anger Expression Scale (AX), the Dula Dangerous Driving Index (DDDI) and a questionnaire about several types of traffic violations. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Chinese DAX yielded a four-factor solution with 20 items. This solution showed the best goodness of fit of the data and acceptable reliability. The validity of the revised DAX was also verified. The aggressive expression forms were positively correlated with dangerous driving behaviors. Using the vehicle to express anger was associated with fines. The aggressive forms were also positively correlated with general anger expression-out and negatively correlated with general anger control. The adaptive expression of anger was positively correlated with anger control but negatively correlated with dangerous driving behaviors, penalty points and fines. Furthermore, young drivers (<30years old) reported more personal and physical aggressive expressions of anger than other drivers. Gender differences were only found in some age groups. Thus, the revised DAX was confirmed to be a reliable and valuable instrument to measure forms of driving anger expression in traffic environments in China.

Speed choice in relation to speed limit and influences from other drivers

DOI:10.1016/S1369-8478(00)00014-0

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Speeding is a general problem in traffic and exploring factors underlying the choice of speed is an important task. In the present paper, based on data from Swedish drivers on 90 km/h roads, drivers’ attitudes towards speeding and influences from other road users on the drivers’ speed choice were investigated. Unobtrusively recorded vehicle speeds were compared with drivers’ responses to questions concerning their speed choice ( N=533). The present investigation replicates a previous study on 50 km/h roads, where a model including measures of attitudes and perceptions about others’ behaviour could explain about 15% of observed behaviour. In the present study, where a majority of the drivers observed exceeded the speed limit, a similar model could explain 41% of the variance in observed speed. Theoretical and practical implications of the results are discussed.

Are narcissists really angrier drivers? An examination of state driving anger among narcissistic subtypes

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2016.06.025

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The present study examined the potential relationships between the 7-factor (Raskin & Terry, 1988) and 3-factor (Ackerman et al., 2011) models of narcissism and state driving anger. A total of 205 (113 women and 92 men) participants were recruited from a student population through in class announcements, on-campus posters, and word of mouth. All participants drove their regular commute and completed a state measure of anger immediately upon arrival at school while in their vehicle. As expected, regression analyses showed that, after controlling for trait driving anger, state anger was predicted by Entitlement and Superiority in the 7-factor model as well as Entitlement/Exploitativeness and Leadership/Authority in the 3-factor model. In contrast narcissistic factors that emphasize Vanity, Exhibitionism, and Grandiosity did not predict state driving anger. This suggests that anger while driving may be more a function of threats to perceived power, control, and position rather than to image and attention seeking among those higher in narcissism. These outcomes support the notion of a multidimensional approach to understanding narcissism in predicting driving anger and potentially other negative driving outcomes.

The impact of Primacy/Recency Effects and Hazard Monitoring on attributions of other drivers

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2016.03.001

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The present study examined the impact of Primacy/Recency Effects and Hazard Monitoring on driver attributions. Participants viewed a simulated near collision from the perspective of a trailing motorist. The amount of error free driving prior to the near collision varied between two groups, where the near incident occurred either early or later in their viewing experience. They were then given the opportunity to provide judgments of the offending driver based on how safe, dangerous, risky, and skilled the driver was in general, and to evaluate their overall performance. Results showed a Primacy Effect dominance in that judgments of the driver were most negative in the early group, but this was moderated by high Hazard Monitoring for ratings of “dangerous” and “safe”. This suggests that judgments of other drivers are likely to be quick and based on early information, but are impacted by personal factors such as a tendency to monitor for hazards.

The relationship between traffic congestion, driver stress and direct versus indirect coping behaviours

DOI:10.1080/001401397188198

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Drivers experiencing rush hour congestion were interviewed using cellular telephones to study stress and coping responses. Measures were taken of each driver''s predisposition to stress (trait stress) as well as their reactions to the experience of either low or high traffic congestion (state stress). Two interviews were conducted during the trip when drivers experienced both low and high congestion conditions. Although state stress was greatest for all drivers experiencing the high congestion condition, a trait X situation interaction was obtained, indicating that stress levels were highest for high trait stress drivers experiencing the congested roadway. In terms of trait coping behaviours, participants indicated a preference for direct over indirect behaviours. A greater variety of direct and indirect behaviours were reported in high congestion. Reports of aggressive behaviours showed the greatest increase from low to high congestion. Comments on the use of cellular telephones in methodology are offered.

Driver boredom: Its individual difference predictors and behavioural effects

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2013.12.004

URL

Driver boredom has received little research attention in efforts to develop understanding of driver behaviour and further road safety. This study aimed to develop understanding of relationships between individual differences and driver boredom as well as between driver boredom and driver behaviour. A self-report questionnaire was developed and used to gather data pertaining to individual differences, driver boredom, and driver behaviour. The sample comprised 1550 male and female drivers aged between 17 and 65+ years. The results of this study show that people who are younger, less conscientious, and less enthusiastic about driving are more likely to pose a high threat to road safety because they are more likely to suffer driver boredom. Those more enthusiastic about driving seem less likely to suffer driver boredom due to their being more engaged in the driving task. Further research should be conducted to test whether engagement in the driving task and levels of perceived stimulation therein explain relations between driver enthusiasm and driver boredom. If this is the case, intervention programmes could be developed and tested in order to encourage engagement in the driving task and so limit driver boredom.

Attenuating the link between threatened egotism and aggression

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01818.x

URL

PMID:17176433

[本文引用: 1]

ABSTRACT Research has found that narcissists behave aggressively when they receive a blow to their ego. The current studies examined whether narcissistic aggression could be reduced by inducing a unit relation between the target of aggression and the aggressor. Experimental participants were told that they shared either a birthday (Study 1) or a fingerprint type (Study 2) with a partner. Control participants were not given any information indicating similarity to their partner. Before aggression was measured, the partners criticized essays written by the participants. Aggression was measured by allowing participants to give their partner loud blasts of noise through a pair of headphones. In the control groups, narcissists were especially aggressive toward their partner. However, narcissistic aggression was completely attenuated, even under ego threat, when participants believed they shared a key similarity with their partner.

Aggression on the road: Relationships between dysfunctional impulsivity, forgiveness, negative emotions, and aggressive driving

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2016.02.010

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This paper presents an investigation into the relationships between two individual characteristics (dysfunctional impulsivity and forgiveness), negative emotions, and self-reported aggressive behaviors. Based on the general aggression model, it was hypothesized that negative emotions mediate the relationship between dysfunctional impulsivity and aggressive driving. In addition, potentially risk-reducing personality traits such as forgiveness may buffer against the effect of negative emotions on aggressive driving. Five hundred and seventy-eight drivers were asked to imagine two potentially aggression-eliciting driving scenarios and to indicate (a) the extent of hypothetically experienced negative emotions and (b) the likelihood of engaging in mild and extremely aggressive driving behaviors in the described situations. Participants also completed measures of impulsivity and trait forgiveness. The results indicated that self-reported mild and extremely aggressive forms of driving behavior were positively correlated with dysfunctional impulsivity and negatively with forgiveness. Negative affect, composed of four negative emotions (anger, hostility, nervousness, and upset), was associated with aggressive driving. An analysis of mediation revealed that negative affect partially mediated the relationship between dysfunctional impulsivity and self-reported mild aggressive acts (e.g., making a hand gesture). However, the direct effect between dysfunctional impulsivity and extremely aggressive behaviors (e.g., ramming a vehicle) in the situation of intense provocation remained statistically unchanged while accounting for negative affect. It was also found that forgiveness mitigated the influence of negative affect on aggressive behaviors, especially on extremely aggressive driving behaviors.

Forgivingness, anger, and hostility in aggressive driving

DOI:10.1016/j.aap.2013.10.017

URL

PMID:24211562

[本文引用: 1]

This study was aimed at investigating the relationship between trait forgivingness, general anger, hostility, driving anger, and self-reported aggressive driving committed by the driver him/herself (“self” scale) and perceiving him/herself as an object of other drivers’ aggressive acts (“other” scale). The Slovak version of questionnaires was administrated to a sample of 612 Slovak and Czech drivers. First, the factor structure of the Driver Anger Indicators Scale (DAIS) was investigated. Factor analyses of the self and other parts of the DAIS resulted in two factors, which were named as aggressive warnings and hostile aggression and revenge. Next, the results showed that from all dependent variables (scales of the DAIS), self-reported aggressive warnings (self) on the road were predicted best by chosen person-related factors. The path model for aggressive warnings (self) suggested that trait forgivingness and general anger were fully mediated by driving anger whereas hostility proved to be a unique predictor of aggressive behavior in traffic. Driving anger was found to be the best predictor of perceptions that other drivers behave aggressively.

Predictors of women's aggressive driving behavior

Does traffic congestion increase driver aggression?

DOI:10.1016/S1369-8478(00)00003-6

URL

[本文引用: 1]

In his recent article about aggressive driving, David Shinar proposed that the classical frustration-aggression hypothesis (Dollard, J., Doob, L., Miller, N., Mowrer, O. & Sears, R. (1939). Frustration and aggression . New Haven, CN: Yale University Press) provides a useful tool for understanding driver aggression (Shinar, D. (1998). Aggressive driving: the contribution of the drivers and situation. Transportation Research Part F, 1 , 137鈥160). According to Shinar's (1998) application of the frustration ggression hypothesis, driver aggression is caused by frustration because of traffic congestion and delays. In the present study, the relationships between exposure to congestion (rush-hour driving) and aggressive violations (DBQ) were investigated in Great Britain, Finland and the Netherlands. Partial correlations showed that the frequency of rush-hour driving did not correlate statistically significantly with driver aggression. Correlations between driving during rush-hour and aggression did not differ in magnitude from those between driving on country roads and aggressive violations. In addition, correlations between exposure to congestion and aggressive violations in countries with large number of vehicles per road kilometre (UK, Netherlands) were not higher than those in a sparsely populated country (Finland). These results from three countries suggest that congestion does not increase driver aggression as directly as suggested by Shinar (1998).

The public place of central libraries: Findings from Toronto and Vancouver

DOI:10.1086/lq.72.3.40039762

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The last decade has seen a relative boom in the construction of central public libraries across North America. The social roles these public institutions play for society is a pressing issue in light of decreasing public funding, advancing information technologies, and an economy increasingly information-driven and decentralized. This article examines the public''s use of two of Canada''s largest central libraries, the Toronto Reference Library and the Vancouver Public Library Central Branch. The data gathered support the notion that these libraries fulfill many of the normative ideals of a successful public place and serve as important resources in the increasingly information-driven, knowledge-based economy. We conclude that private market interests encroaching upon this institution, and not advances in information technologies, represent a threat to its multifaceted role as a successful public place.

Sharing social space with strangers: Setting, signalling and policing informal rules of driving etiquette. Proceedings of the 2015 Australasian Road Safety Conference

Recent research suggests that aggressive driving may be influenced by driver perceptions of their interactions with other drivers in terms of ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ behaviour. Drivers appear to take a moral standpoint on ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ driving behaviour. However, ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ in the context of road use is not defined solely by legislation, but includes informal rules that are sometimes termed ‘driving etiquette’. Driving etiquette has implications for road safety and public safety since breaches of both formal and informal rules may result in moral judgement of others and subsequent behaviours designed to punish the ‘offender’ or ‘teach them a lesson’. This paper outlines qualitative research that was undertaken with drivers to explore their understanding of driving etiquette and how they reacted to other drivers’ observance or violation of their understanding. The aim was to develop an explanatory framework within which the relationships between driving etiquette and aggressive driving could be understood, specifically moral judgement of other drivers and punishment of their transgression of driving etiquette. Thematic analysis of focus groups (n=10) generated three main themes: (1) courtesy and reciprocity, and the notion of two-way responsibility, with examples of how expectations of courteous behaviour vary according to the traffic interaction; (2) acknowledgement and shared social experience: ‘giving the wave’; and (3) responses to breaches of the expectations/informal rules. The themes are discussed in terms of their roles in an explanatory framework of the informal rules of etiquette and how interactions between drivers can reinforce or weaken a driver’s understanding of driver etiquette and potentially lead to driving aggression.

‘You’re a bad driver but I just made a mistake’: Attribution differences between the ‘victims’ and ‘perpetrators’ of scenario-based aggressive driving incidents

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2011.01.001

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Driver aggression is an increasing concern for motorists, with some research suggesting that drivers who behave aggressively perceive their actions as justified by the poor driving of others. Thus attributions may play an important role in understanding driver aggression. A convenience sample of 193 drivers (aged 17–36) randomly assigned to two separate roles (‘perpetrators’ and ‘victims’) responded to eight scenarios of driver aggression. Drivers also completed the Aggression Questionnaire and Driving Anger Scale. Consistent with the actor–observer bias, ‘victims’ (or recipients) in this study were significantly more likely than ‘perpetrators’ (or instigators) to endorse inadequacies in the instigator’s driving skills as the cause of driver aggression. Instigators were significantly more likely attribute the depicted behaviours to external but temporary causes (lapses in judgement or errors) rather than stable causes. This suggests that instigators recognised drivers as responsible for driving aggressively but downplayed this somewhat in comparison to ‘victims’/recipients. Recipients and instigators agreed that the behaviours were examples of aggressive driving but instigators appeared to focus on the degree of intentionality of the driver in making their assessments while recipients appeared to focus on the safety implications. Contrary to expectations, instigators gave mean ratings of the emotional impact of driving aggression on recipients that were higher in all cases than the mean ratings given by the recipients. Drivers appear to perceive aggressive behaviours as modifiable, with the implication that interventions could appeal to drivers’ sense of self-efficacy to suggest strategies for overcoming plausible and modifiable attributions (e.g. lapses in judgement; errors) underpinning behaviours perceived as aggressive.

Finding the next cultural paradigm for road safety

Road rage and collision involvement

DOI:10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.4.384

URL

PMID:17511573

[本文引用: 1]

OBJECTIVES: To assess the contribution of road rage victimization and perpetration to collision involvement. METHODS: The relationship between self-reported collision involvement and road rage victimization and perpetration was examined, based on telephone interviews with a representative sample of 4897 Ontario adult drivers interviewed between 2002 and 2004. RESULTS: Perpetrators and victims of both any road rage and serious road rage had a significantly higher risk of collision involvement than did those without road rage experience. CONCLUSIONS: This study provides epidemiological evidence that both victims and perpetrators of road rage experience increased collision risk. More detailed studies of the contribution of road rage to traffic crashes are needed.

Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises

DOI:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Confirmation bias, as the term is typically used in the psychological literature, connotes the seeking or interpreting of evidence in ways that are partial to existing beliefs, expectations, or a hypothesis in hand. The author reviews evidence of such a bias in a variety of guises and gives examples of its operation in several practical contexts. Possible explanations are considered, and the question of its utility or disutility is discussed.

Effects of driving anger on driver behavior - Results from naturalistic driving data

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2016.10.019

URL

[本文引用: 2]

There is a positive relationship between driving anger and near-crash or crash risk. However, it remains unclear if anger in fact contributes to traffic accidents and whether this happens due to cognitive overload or aggressive driving behaviors. This study investigated how anger affects driving behavior based on naturalistic driving data from the second Strategic Highway Research Program (SHRP 2). Ten-minute trip segments were analyzed in which drivers exhibited anger with regard to driving errors, violations, and aggressive expressions. This data was compared to a matched baseline consisting of the same drivers not exhibiting anger. Results showed that anger resulted in more frequent aggressive driving behaviors but did not increase driving error frequency. Anger consequently creates danger due to deliberate behaviors rather than because of cognitive overload. In congruence with this finding, only anger triggered by threats, provocations, and frustrations increased the frequency of deliberate infringements. In contrast, anger due to having conflicts with someone on the phone or with a passenger was not linked to any type of aberrant driving behavior. Finally, severe displays of anger were accompanied by more violations as compared to slight or marked anger.

The determinants of driving aggression among Polish drivers

Motorcycle riders’ self-reported aggression when riding compared with car driving

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2015.11.006

URL

Aggressive driving has been shown to be related to increased crash risk for car driving. However, less is known about aggressive behaviour and motorcycle riding and whether there are differences in on-road aggression as a function of vehicle type. If such differences exist, these could relate to differences in perceptions of relative vulnerability associated with characteristics of the type of vehicle such as level of protection and performance. Specifically, the relative lack of protection offered by motorcycles may cause riders to feel more vulnerable and therefore to be less aggressive when they are riding compared to when they are driving. This study examined differences in self-reported aggression as a function of two vehicle types: passenger cars and motorcycles. Respondents (n=247) were all motorcyclists who also drove a car. Results were that scores for the compositedrivingaggression scale were significantly higher than on the compositeridingaggression scale. Regression analyses identified different patterns of predictors for driving aggression from those for riding aggression. Safety attitudes followed by thrill seeking tendencies were the strongest predictors fordrivingaggression, with more positive safety attitudes being protective whilst greater thrill seeking was associated with greater self-reported aggressive driving behaviour. Forridingaggression, thrill seeking was the strongest predictor (positive relationship), followed by self-rated skill, such that higher self rated skill was protective against riding aggression. Participants who scored at the 85th percentile or above for the aggressivedrivingand aggressiveridingindices had significantly higher scores on thrill seeking, greater intentions to engage in future risk taking, and lower safety attitude scores than other participants. In addition participants with the highest aggressivedrivingscores also had higher levels of self-reported past traffic offences than other participants. Collectively, these findings suggest that people are less likely to act aggressively when riding a motorcycle than when driving a car, and that those who are the most aggressive drivers are different from those who are the most aggressive riders. However, aggressive riders and drivers appear to present a risk to themselves and others on road. Importantly, the underlying influences for aggressive riding or driving that were identified in this study may be amenable to education and training interventions.

Identifying beliefs underlying pre-drivers' intentions to take risks: An application of the theory of planned behaviour

DOI:10.1016/j.aap.2015.12.024

URL

PMID:26803598

[本文引用: 1]

Novice motorists are at high crash risk during the first few months of driving. Risky behaviours such as speeding and driving while distracted are well-documented contributors to crash risk during this period. To reduce this public health burden, effective road safety interventions need to target the pre-driving period. We use the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) to identify the pre-driver beliefs underlying intentions to drive over the speed limit (N=77), and while over the legal alcohol limit (N=72), talking on a hand-held mobile phone (N=77) and feeling very tired (N=68). The TPB explained between 41% and 69% of the variance in intentions to perform these behaviours. Attitudes were strong predictors of intentions for all behaviours. Subjective norms and perceived behavioural control were significant, though weaker, independent predictors of speeding and mobile phone use. Behavioural beliefs underlying these attitudes could be separated into those reflecting perceived disadvantages (e.g., speeding increases my risk of crash) and advantages (e.g., speeding gives me a thrill). Interventions that can make these beliefs safer in pre-drivers may reduce crash risk once independent driving has begun.

Aggression, emotional self-regulation, attentional bias, and cognitive inhibition predict risky driving behavior

DOI:10.1016/j.aap.2017.10.006

URL

PMID:29049929

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract The present study explored whether aggression, emotional regulation, cognitive inhibition, and attentional bias towards emotional stimuli were related to risky driving behavior (driving errors, and driving violations). A total of 117 applicants for taxi driver positions (89% male, M age=36.59years, SD=9.39, age range 24-62years) participated in the study. Measures included the Ahwaz Aggression Inventory, the Difficulties in emotion regulation Questionnaire, the emotional Stroop task, the Go/No-go task, and the Driving Behavior Questionnaire. Correlation and regression analyses showed that aggression and emotional regulation predicted risky driving behavior. Difficulties in emotion regulation, the obstinacy and revengeful component of aggression, attentional bias toward emotional stimuli, and cognitive inhibition predicted driving errors. Aggression was the only significant predictive factor for driving violations. In conclusion, aggression and difficulties in regulating emotions may exacerbate risky driving behaviors. Deficits in cognitive inhibition and attentional bias toward negative emotional stimuli can increase driving errors. Predisposition to aggression has strong effect on making one vulnerable to violation of traffic rules and crashes. Copyright 2017. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Driving citations and aggressive behavior

DOI:10.1080/15389588.2012.654412

URL

PMID:22607257

[本文引用: 3]

Background: Anger and driving have been examined in a number of studies of aggressive drivers and in drivers with road rage using various psychological and environmental study variables. However, we are not aware of any study that has examined the number of driving citations (an indication of problematic driving) and various forms of anger not related to driving.

It's the thought that counts: Developing a model of driver aggression by exploring the underlying cognitive processes

(While driver aggression is associated with crash involvement, understanding of the underlying causes of, and motivations for it is limited. To address this, the research investigated the psychological processes involved in driver aggression, focusing on how beliefs and attitudes influence the behaviour. In doing so, the research also informed the development of a model of driver aggression based on the General Aggression Model. The results suggested that driver aggression is fuelled by a desire to modify the driving behaviour of other motorists, and that it may reflect a self-fulfilling prophecy stemming from negative views regarding standards of driving behaviour.

Can’t we all just get along? A qualitative investigation of the cognitive processes motivating driver aggression

DOI:10.1021/jp207968b

URL

[本文引用: 4]

Although driver aggression has been identified as contributing to crashes, current understanding of the fundamental causes of the behaviour is poor. Two key reasons for this are evident. Firstly, existing research has been largely atheoretical, with no unifying conceptual framework guiding investigation. Secondly, emphasis on observable behaviours has resulted in limited knowledge of the underlying thought processes that motivate behaviour. Since driving is fundamentally a social situation, requiring drivers to interpret on-road events, insight regarding these perception and appraisal processes is paramount in advancing understanding of the underlying causes. Thus, the current study aimed to explore the cognitive appraisal processes involved in driver aggression, using a conceptual model founded on the General Aggression Model (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). The present results reflect the first of several studies testing this model. Participants completed 3 structured driving diaries to explore perceptions and cognitions. Thematic analysis of diaries identified several cognitive themes. The first, ‘driving etiquette’ concerned an implied code of awareness and consideration for other motorists, breaches of which were strongly associated with reports of anger and frustration. Such breaches were considered intentional; attributed to dispositional traits of another driver, and precipitated the second theme, ‘justified retaliation’. This theme showed that drivers view their aggressive behaviour as warranted, to convey criticism towards another motorist’s etiquette violation. However, the third theme, ‘superiority’ suggested that those refraining from an aggressive response were motivated by a desire to perceive themselves as ‘better’ than the offending motorists. Collectively, the themes indicate deep-seated and complex thought patterns underlying driver aggression, and suggest the behaviour will be challenging to modify. Implications of these themes in relation to the proposed model will be discussed, and continued research will explore these cognitive processes further, to examine their interaction with person-related factors.

Aggressive driving: The contribution of the drivers and the situation

DOI:10.1016/S1369-8478(99)00002-9

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Aggressive driving is defined in terms of the frustration-aggression model. In that context aggressive driving is a syndrome of frustration-driven behaviors, enabled by the driver's environment. These behaviors can either take the form of instrumental aggression--that allows the frustrated driver to move ahead at the cost of infringing on other road users' rights (e.g., by weaving and running red lights)--or hostile aggression which is directed at the object of frustration (e.g., cursing other drivers). While these behaviors may be reflective of individual differences in aggression, it is argued that the exclusive focus on the characteristics of the aggressive drivers and how to control them is short-sighted. Instead, this paper proposes a multi-factor approach to the problem. Five studies conducted so far tend to support this approach, by showing that specific aggressive behaviors--such as honking and running red lights--are associated with cultural norms, actual and perceived delays in travel, and congestion. Ergonomics-oriented approaches that involve environmental modifications are proposed.

Aggressive driving: An observational study of driver, vehicle, and situational variables

DOI:10.1016/S0001-4575(03)00037-X

URL

PMID:15003588

[本文引用: 3]

Over 2000 aggressive driving behaviors were observed over a total of 7202h at six different sites. The behaviors selected for observation were those that are commonly included in ‘aggressive driving’ lists, and they consisted of honking, cutting across one or more lanes in front of other vehicles, and passing on the shoulders. In addition, an exposure sample of 7200 drivers were also observed at the same times and places. Relative risks (RRs) and odds ratios (ODs) were calculated to show the relative likelihood that different drivers under different conditions will commit aggressive behaviors. The rate of aggressive actions observed in this study decreased from the most frequent behavior of cutting across a single lane, through honking, and to the least frequent behaviors of cutting across multiple lanes and passing on the shoulders. Relative to their proportion in the driving population, men were more likely than women to commit aggressive actions, and the differences increased as the severity of the action increased. Drivers who were 45 years old or older were less likely to drive aggressively than younger ones. The presence of passengers was associated with a slight but consistent reduction in aggressive driving of all types; especially honking at other drivers. There was a strong linear association between congestion and the frequency of aggressive behaviors, but it was due to the number of drivers on the road. However, when the value of time was high (as in rush hours), the likelihood of aggressive driving—after adjusting for the number of drivers on the road—was higher than when the value of time was low (during the non-rush weekday or weekend hours). The results have implications for driver behavior modifications and for environmental design.

Attitudes, norms and driving behaviour: A comparison of young drivers in South Africa and Sweden

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2013.07.001

URL

[本文引用: 3]

Culture is increasingly recognised among traffic psychologists to be a factor influencing driving behaviour. This study examines whether a cultural background characterised by rapid social change and high levels of violence and aggression, as in the South African context, has any discernible influences on driving standards or the behaviour of individual drivers. The experiences and attitudes of young drivers in South Africa are compared with a group of young drivers from Sweden, a country whose society has exhibited high levels of stability and where road user behaviour is renowned for its restraint and compliance with regulations.The two cohorts provide information about their exposure to traffic injuries, their attitudes to other drivers and to a range of traffic offences, and to the types of behaviour they personally engage in. Among the South African respondents the notion of a declining standard of driving emerges very clearly, and specific new norms of driving are identified. Such norms are explained to be a consequence of new social values or challenges inherent within contemporary South African society. (C) 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Towards a comprehensive model of driver aggression: A review of the literature and directions for the future.

Development and preliminary validation of a scale of driving moral disengagement as a tool in the exploration of driving aggression

DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2017.01.011

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Aggressive driving has been found to result in road collisions which are a major cause of injury, fatality and financial cost in motorised countries. Qualitative and survey based studies suggest that drivers use justifications or explanations of their aggressive driving that bear strong resemblance to Bandura’s mechanisms of moral disengagement. The aim of the current study was to explore the applicability of moral disengagement to the driving context using a purpose-adapted scale, the Driving Moral Disengagement Scale. A convenience sample of general drivers (N=294) responded to an on-line survey comprised of measures of trait anger, driving anger (DAX revised), moral disengagement and driving moral disengagement. Factor analysis allowed for reduction of the new scale from 23 items to 13 items, and this shortened Driving Moral Disengagement Scale (DMDS) had good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha=.83). Scree plot criteria indicated a one factor solution accounting for 34.34% of the variance. Bivariate correlations on the shortened DMDS revealed significant and positive relationships with measures of driving aggression, moral disengagement, trait anger and driving anger,r=.28–.55. Moreover the strength of the association between driving aggression and moral disengagement was greater than that with driving anger. Hierarchical regression revealed driving moral disengagement as the strongest significant predictor of driving aggression, accounting for 18% of the unique variation in the DV, and suggesting this may be a more useful predictor than driving anger. In addition, significant differences between participants’ mean scores for moral disengagement in everyday situations and their driving moral disengagement scores support the interpretation that drivers may behave differently from their ‘usual’ selves when driving, and that the driving context may encourage both greater moral disengagement and greater tendency towards aggressive responses. Chi square analysis indicated that those who scored high on driving moral disengagement were significantly more likely to report aggressive responses to driving situations than those with low driving moral disengagement scores (with a large effect size,φ=.42). This suggests that the DMDS may be useful for future driving aggression research. Implications for intervention are that aiming to alert drivers to their usual self-censure mechanisms or to prevent the tendency to moral disengagement while driving may be effective in reducing driving aggression and the risky or dangerous responses associated with it on road.

The accident-prone automobile driver; A study of the psychiatric and social background

DOI:10.1176/ajp.106.5.321

URL

PMID:18143862

[本文引用: 1]

[Abstract unavailable]

If you can't join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1058

URL

PMID:11761307

[本文引用: 1]