1 引言

意义(Meaning)在人类生活中扮演着核心角色, 人不能忍受没有意义的生活(Wong, 2014)。生命意义体验(Meaning In Life)与生活中一系列积极和健康指标紧密相关, 如快乐、幸福、生活满意度、复原力、困难应对技巧、希望、感恩、身体健康、自尊和授权能力等, 而缺乏意义则与一系列消极和非健康指标, 如抑郁、焦虑、创伤后应激障碍、酒精和毒品滥用、物质主义和无聊等联系在一起(Schulenberg, Baczwaski, & Buchanan, 2014)。生命意义无论对生活幸福还是身体健康都有重要作用(Heintzelman & King, 2014)。

然而对于人们何时寻求意义, 即生命意义寻求的起因是什么, 学者们的观点却并不相同。Frankl (1963)认为, 寻求生命意义对每个人来说都是一个自然的心理过程, 个体对意义的寻求是恒久持续的, 对意义的追求永不满足。然而, Baumeister (1991)则认为生命意义的寻求是由缺失驱动的, 主要发生于基本需要未能满足的个体或需求未能满足的时候。意义一旦得以恢复, 人们便失去了继续寻求的动力。前者被称为“生命肯定观(Life affirming hypothesis)”, 后者被称为“缺失恢复观(Deficit correcting hypothesis)” (Steger, 2013)。到目前为止, 两种观点都获得了一些实证证据的支持, 但也都有一些矛盾证据存在, 研究者还无法得出确定的结论。

本文在介绍已有观点及其证据的基础上, 剖析了现有研究的局限, 并提出了一个假设模型, 以阐释意义寻求产生的前提, 以期为未来的研究提供理论框架。为使以下讨论更为严谨, 首先需要对生命意义以及生命意义寻求的内涵进行界定。

2 生命意义及寻求的界定

生命意义(Meaning In Life)由三种成分(Tripartite)构成的观点在慢慢取得共识(Martela & Steger, 2016; George & Park, 2017)。比如, King, Hicks, Krull和Del Gaiso (2006)等认为“当感觉有超越细节和瞬时的重要性(Significance)、有目标(Purpose)、或者有超越混沌的一致性(Coherence)时, 生活就会产生意义感”。George和Park (2016)等把生命意义定义为“一个人的生活在多大程度上可以理解(Coherence), 被有价值目标指引和驱动(Purpose), 并且对这个世界重要(Mattering)”。Martela和Steger (2016)持有相似的观点, 认为人们在对自己的生活是否有意义做出判断时所依据的内容包括三种成分:一致性(Coherence, 认知成分)、目的(Purpose, 动机成分)和重要性(Significance或Mattering, 情感成分)。在这一理解的基础上, Steger等把生命意义寻求界定为, 人们在确立或增加对其生命的含义、重要性和目的性的理解时所表现出来的愿望和努力的强度和活动性(Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan, Lorentz, 2008a)。在本文中, 我们采纳上述定义, 把凡是追求对自己生命(或生活)的理解、发现和确立生活目的、或者寻求生命重要感的动机和努力都划定在生命意义寻求的范畴内。

3 生命意义寻求起因的两种假说

3.1 缺失恢复观(Deficit correcting hypothesis)

个体在何种条件下会寻求生命的意义?Baumeister (1991)认为, 生命意义寻求主要发生在那些遭遇挫折的个体身上。按照这种观点, 一个人在未能实现生活目标, 或者面对创伤性事件时更愿意寻求意义。因为在这种情况下, 个体需要对生活的重大方面做出调整, 并通过建立新的意义结构重新规划自我的存在。Steger (2013)也认为, 对于意义体验, 每个人可能都存在一个独特的最佳水平, 个体总是为保持这一水平而努力。这种努力类似于有机体的新陈代谢:为保持一种动态平衡, 在缺乏意义时个体会努力寻求, 而当意义超过某一水平时个体就会减弱寻求, 最终使得意义体验大体维持在某一水平附近。

缺失恢复观的主旨在于, 每个人都有一个独特但大致稳定的生命意义体验水平, 寻求的原因或者动力源于意义的损坏或缺损, 意义一旦恢复, 个体的寻求努力便会减弱, 从而使意义体验水平始终维持在某一最佳水平附近。根据这一观点所描述的生命意义存现和寻求的关系如图1中的粗实线所示。这是一条大致的三次曲线, 当意义体验(存现)水平很低时, 意义寻求水平最高, 随着体验水平的提高, 寻求努力会逐步降低。曲线的中部有一个平台期, 此时体验水平继续升高, 而寻求水平大体保持稳定。在这个平台期之后, 随着意义体验水平的继续提高, 意义寻求的努力会逐步减弱, 并且随着意义体验水平的继续增加, 意义寻求水平有迅速减弱的趋势。

图1

图1

生命意义体验与生命意义寻求之间的关系

资料来源:The psychology of meaning, 第11章Wrestling with our better selves: The search for meaning in life (Steger, 2013)。

这一观点得到许多实证研究的支持。Steger, Oishi和Kashdan等(2009)使用自编的生命意义问卷(MLQ-P和MLQ-S)调查了来自全球各地, 年龄从25岁到64岁的6764名成年人。结果发现, 人们的生命意义体验水平(MLQ-P分数)与寻求水平(MLQ-P分数)呈现图1所示的趋势。在三条拟合两个变量关系的曲线中(分别为1次、2次和3次曲线), 反映缺失恢复观的粗实线(3次曲线)对数据拟合得最好。根据这条曲线, 生命意义寻求的最高水平出现在生命意义体验水平最低时。随着体验水平的升高, 寻求水平逐步降低。在曲线的中部, 随着意义体验水平的提高, 出现了一个寻求水平几乎不再变化的平台。过了这个阶段之后, 意义寻求水平随着体验水平的上升而出现急剧的下降。

大量意义建构(Meaning making)研究为缺失恢复观提供了更直接的证据。意义建构理论(Meaning Making Theory, MMT)认为, (a)每个人都有一套所谓的“整体意义” (或“整体信念系统”), 它为人们解释自己的经历和行为动机提供认知框架; (b)当个体遭遇挑战整体意义的事件时, 就会对其进行评价并赋予其意义; (c)事件被赋予的意义与整体意义的不一致导致个体体验到痛苦, 并且不一致的程度决定了痛苦程度; (d)不一致导致的痛苦会激活意义建构过程; (e)通过意义建构, 个体努力减少事件被赋予的意义和整体意义之间的差异, 恢复“世界是有意义的、生命是值得活的感觉”; (f)重构意义是对应激事件的适应。那些突然出现且无法预测的创伤事件破坏了整体信念系统。因此, 创伤性事件所以痛苦的原因, 在于它们破坏了人们关于自己和世界的许多基本假设, 个体在这种痛苦之下便会开启生命意义寻求的过程, 即意义缺失或破坏导致了意义寻求(Park & George, 2013; 赵娜, 马敏, 辛自强, 2017)。

实证研究支持上述假设。Schwartzberg和Janoff-Bulman (1991)调查发现, 90%失去亲人的大学生会问“为什么死的是我的父亲/母亲”。Davis等发现, 人们在经历丧失或创伤性事件之后, 会沉浸于对死亡的思考并反复寻找事件的原因(Davis, Lehman, Wortman, Silver, & Thompson, 1995)。Uren和Wastell (2002)发现, 超过80%失去孩子的母亲会努力试图弄明白孩子的死亡原因。许多逆境应对的研究显示, 人们面对创伤事件时经常问自己的问题就是“为什么是我?” (Thompson, 1991)。在总结了对强奸受害者、乳腺癌患者和HIV病毒感染者进行的一系列研究后, Taylor (1983)指出, 在对威胁性事件的适应过程中, 寻求意义往往是第一个过程。

3.2 生命肯定观(Life affirming hypothesis)

然而, 按照Frankl (1963)的观点, 人是区别于其它动物的灵性(Spirituality)存在, 灵性决定了人的生活是以意义为核心的, 即每个人都存在着理解世界和超越自身的动机。追求意义是人灵性的一种表达, 所以意义寻求应该是一个永无休止的过程(Wong, 2014)。一个人越是体验到意义, 越是具有更强的寻求意义的动机。上述观点被Steger (2013)称为“生命肯定观”。

这一观点同样得到实证证据的支持。Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan和Otake (2008b)发现, 人们在生命意义问卷的意义寻求分量表上的平均得分是24.8分(共5个项目, 在1~7点量表上评分), 也就是说, 大多数个体对诸如“我正在寻找自己生活的意义”这样的描述给予了肯定的评价。换句话说, 人们大多数时候是关心生活的目的, 愿意探索生命意义问题的。这项研究还显示, 虽然高意义体验水平的大多数人缺乏继续寻找意义的动力, 但确实有少部分个体, 虽然意义体验水平已经很高, 但仍然报告拥有寻求意义的强烈动机。更重要的是, 生命意义寻求与一些象征积极品质的人格特征相联系, 表明意义寻求至少是一部分人的持续性动机。比如, Steger等发现, 生命意义寻求与开放性、专注和探寻兴趣(Investigative interests)等特质强相关(Steger et al., 2008b)。Vess, Routledge, Landau和Arndt等(2009)在关于恐惧管理理论的研究中也发现, 具有低结构需要(Personal Need for Structure, PNS)的个体在面对死亡威胁时, 并不像高结构需要个体那样, 为了恢复意义而重新确认其珍视的结构, 而是与之相反, 他们愿意探索新东西、发现新事物。

3.3 对已有证据的分析和评价

纵览已有文献会发现, 现有证据之间充满着混乱和矛盾。例如, Steger等(2008a)以美国被试为样本发现, 意义体验与意义寻求呈现负相关, 意义体验越低, 追求意义的动机越高, 这支持了缺失恢复观。然而, 这一现象并没有在其它文化下得到重复验证。在一个中国本科生样本中, 刘思斯与甘怡群(2010)没有观察到两者之间的相关。另外, 在日本的一个年轻人样本中, 两者之间却是正相关关系(Steger et al., 2008b)。同样, 支持与反对生命肯定观的证据也同时存在。一项探索生命意义体验与寻求随年龄变化趋势的研究发现, 随着年龄的增长, 生命意义体验水平有缓慢上升的趋势, 而生命意义寻求水平则缓慢下降(Steger et al., 2009, Bodner, Bergman, & Cohen-Fridel, 2014)。生命意义体验随年龄增加而增强表面上支持生命肯定观, 随着年龄的增长, 人们体验到的意义越来越多。然而, 意义寻求随年龄增加而下降则又支持缺失恢复观。矛盾现象最主要的证据来自于对意义体验与寻求关系的类型研究。Dezutter等(2014)调查了8492名美国大学生, 依据意义体验与意义寻求之间的关系, 通过聚类分析将被试分为了五种类型:低体验低寻求、低体验高寻求、高体验低寻求、高体验高寻求以及未分化型, 每种类型占总体的比例依次为9%、15%、18%、23%、35%。由此可见, 意义体验与意义寻求的关系非常复杂。意义体验与意义寻求似乎并不存在必然的关系。缺乏意义体验, 有些个体会启动意义寻求动机, 而另外一些个体则不会。拥有高意义体验, 有些个体仍然会选择寻找意义, 而另一些则停止寻找。也就是说, 缺失恢复观与生命肯定观似乎都是片面的。

3.4 混乱证据背后的原因分析

我们认为, 导致研究之间相互矛盾的原因有以下几个方面:

其一, 对意义寻求的测量不够精确。以上所列举的大多数证据, 所选用的测量工具均是Steger编制的的生命意义量表(MLQ) (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006)。该量表包含10个项目, 分为两个分量表:生命意义体验(Presence of meaning)与生命意义寻求(Search for meaning)。该量表信效度良好, 所测构念单纯, 并且同时测量了生命意义感的情感成分和动机成分, 因此被广泛使用(Schulenberg et al., 2014)。不过, 由于其项目过于笼统和抽象, 故而难以反应生命意义寻求的细节(Wong, 2014)。例如, 被试如果不赞同 “我正在寻觅人生的一个目的或使命”这一项目, 可能是他或她因为预期找不到意义而停止了寻求, 也可能是已经获得了意义, 觉得没有继续寻求的必要。由于测量精度较差, 无法有效区分不同的被试类型, 因而也就无法准确预测生命意义体验与寻求之间的关系。另外, 该量表也没有区分意义寻求的内容, 即个体寻求的是什么, 是对生活的理解(Coherence)、目的(Purpose), 还是生活的价值(Significance)。虽然三种成分之间相互影响, 但彼此具有一定的独立性, 不能等同(Park, 2010)。

其二, 静态地看待意义体验与寻求之间的关系。利用量表探查意义体验与寻求之间关系的研究, 都潜在假设两者具有特质属性, 具有跨时间与跨情景的一致性。的确, 一年内的追踪研究发现, 无论是前测的意义体验, 还是意义寻求, 均与后测构念具有中等程度的正相关(Steger & Kashdan, 2007; 张姝玥, 许燕, 2012)。然而, 从生命全程来看, 无论是意义体验, 还是意义寻求, 都在发生变化。Bodner等(2014)发现, 意义寻求在18至24岁到达高峰, 之后呈持续下降趋势; 而意义体验则不同, 18岁之后开始下降, 在24岁左右达到低谷, 继而又开始持续上升。这一研究表明, 无论是意义体验, 还是意义寻求, 一定程度上是动态、波动的。除此之外, 意义寻求动机还会受到情景因素的影响, 压力事件就是其中之一。Park与Baumeister (2017)认为, 生命意义感的重要功能之一, 是为人提供一种世界可以预测、可以控制的感觉。然而, 压力事件通常不可控制, 这对生命意义感形成了威胁。因此, 压力事件会驱动个体寻求意义。他们的研究发现, 指导被试想象未来生活中的压力事件, 会提升个体的意义寻求水平。类似的发现来自Graeupner和Coman (2017)的研究, 当个体觉知到被他人排斥时, 会启动意义寻求, 进而更可能相信迷信和阴谋论。这些证据都表明意义寻求和意义体验都是动态的, 随情景变化的。

第三, 没有在需要和动机关系框架下探索意义体验与意义寻求之间的关系。需要是有机体内部的某种缺乏或不平衡状态, 动机则是激发并维持个体活动朝向某一目标的心理倾向和动力。动机根植于需要, 需要是动机产生的前提。因此, 意义寻求动机由意义需求诱发。我们认为, 意义需求不单单由当下的意义体验水平高低决定, 而是取决于当下生命意义体验的绝对水平与渴求状态之间的差距。缺失恢复观认为, 维持机体身心健康需要一定的意义水平, 当重大创伤出现, 个体觉知到当下的意义水平远低于目标意义水平时, 意义需求就会出现, 从而驱动个体寻求意义, 恢复意义水平。然而, 缺失恢复观没有注意到, 即使个体的生命意义体验维持在较高水平, 如果有更高的意义目标出现, 形成意义需求, 仍然会激发个体寻求意义的动机。特质层面的研究发现, 即使在控制意义体验水平之后, 偏相关结果仍然显示, 好奇心、经验开放性、宜人性、尽责性、认知需求以及趋近动机高的个体, 有着更强的意义寻求倾向(Steger et al, 2008a)。这表明某些特质对意义寻求具有增益性, 无论意义体验水平高低, 都会持续地追求意义。除了特质之外, 某些情景因素也能够显著地驱动意义寻求。King与Hicks (2009)认为, 能够诱发个体敬畏情绪的情景, 就是诱因之一。敬畏的诱发源有很多, 可以是权威的领导者与上帝, 也可以来自壮美的景观 (如龙卷风、大教堂、音乐等), 以及人类的伟大创举(如进化论、精神分析论等科学理论) (董蕊, 彭凯平, 喻丰, 2013)。知觉到的浩大(Perceived vastness)以及顺应的需要(A need for accommodation)被认为是敬畏的两个核心特征(Keltner &, Haidt, 2003)。浩大意味着面前的事物更强大, 更具意义。顺应指的则是调整已有心理图式以适应新经验的过程。我们认为, 这些策略或过程包含着意义寻求, 即寻求新的意义图式的过程。缺失恢复观只看到意义受损会驱动意义寻求, 没有意识到积极、正性、更浩大的诱因也是驱动意义寻求的因素。与缺失恢复观不同的是, 生命肯定观主张, 即使是那些高意义体验的个体, 也有持续寻求意义的动机。意义体验与意义寻求双高个体的存在, 是这一观点的有力佐证。然而, 高体验低寻求个体同样存在, 并且与双高个体相比, 前者的心理健康状况也并未受损(Dezutter et al., 2014)。这表明即使不再寻求意义, 维持一定的意义体验对保持健康已经足够。这一证据揭示了生命肯定观的局限性, 并非所有个体都在不断地寻求意义。

4 意义寻求的前置因素模型

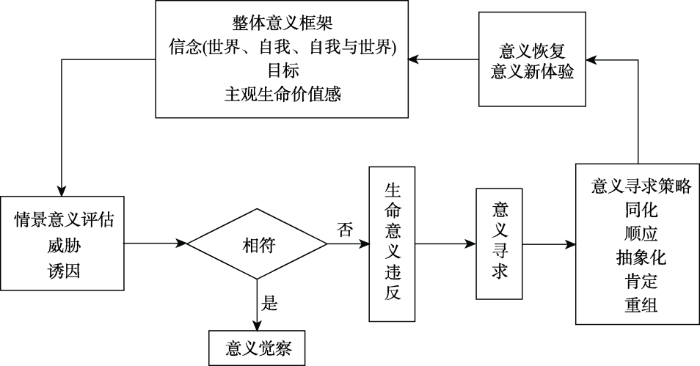

综上所述, 缺失恢复观与生命肯定观都不足以解释现有证据。简言之, 意义寻求并非到达一定水平就衰减, 也并非持续不断, 它的启动或发生需要一定前提条件。查阅国内外文献, 未发现对此进行阐释的理论或模型。基于意义建构模型(George & Park, 2016; 赵娜, 马敏, 辛自强, 2017)、意义维持模型(Proulx, Inzlicht, & Harmon- Jones, 2012; 左世江, 黄旎雯, 王芳, 蔡攀, 2016)以及相关实证研究, 我们提出意义寻求的“前置因素模型”, 以阐释启动意义寻求的条件(见图2)。

图2

新模型是对缺失恢复观与生命肯定观的继承和发展。与缺失恢复观一致的是, 新模型同样认为, 当意义受损后个体会启动寻求以恢复意义。不同的是, 新模型并不认为意义到达一定水平时寻求动机必然下降。与生命肯定观一致的是, 意义寻求可能持续存在, 但这需要一定的条件。具体来说, 当意义体验维持在一个高水平后, 更高水平的诱因存在是启动意义寻求的前提条件。这一诱因可以是个体是否意识到有更值得追求的意义存在, 也可以是某种情景性的因素。

4.1 基本观点

借鉴意义建构模型(The meaning makeing model, Park & George, 2013)的基本思路, 我们同样认为意义寻求源于情景意义评估与整体意义框架不符所诱发的意义违反。整体意义框架由三种元素构成:个体的信念系统(Global beliefs)、生活的首要目标(Global goals)以及主观生命价值感(Subjective sense of significance)。信念系统构成了个体解释生活经验的核心图式, 是个体理解自我、世界、自我与世界关系的基础框架。信念的种类很多, Koltko-Rivera (2004)将其分为人性、意志、认知、行为、人际、真理、世界等七大类共计42个维度。以人性信念为例, 包含了人性善恶、可改变性以及复杂性三个子维度。整体目标指的是所渴求事件、过程或结果的内部表征(Austin & Vancouver, 1996), 个体通常报告的整体目标有五类:关系、宗教、知识、成就与工作(Emmons, 2003)。目标以层级的形式组织, 上位目标更能代表整体目标(Vallacher & Wegner, 1987)。整体意义框架中的第三个成分是主观生命价值感, 是个体对自己生命价值的主观判断。整体意义框架中的三元素是个体与环境多次相互作用的结果, 基于以上元素, 个体形成自身独特且相对稳定的生命意义体验, Hooker, Masters和Park (2018)将其称之为特质生命意义感, 用来区别情景意义评估后生命意义体验的变化。特质生命意义感是相对稳定的。情景意义评估指的是在一定的背景下, 个体如何理解、建构、解释特定事件。对情景事件的意义评估可能与整体意义框架相符, 也可能不符。相符时, 个体会觉察到意义(Meaning detecting) (King & Hicks, 2009)。两者相符上升到意识层面后, 个体会觉察到事情在正确的方向上(The rightness of direction), 有一种“对, 就是这样”的感觉(Mangan, 2001)。意义觉察可以发生在个体忘我地投入某种活动所产生的心流(Flow)体验(Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), 或者当目标由内在动机驱使的时候(Ryan & Deci, 2000)。

当情景意义评估与整体意义框架不符时, 意义违反就出现了。意义违反(Meaning violation)是意义维持模型使用的术语, 指的是当前经历与个体根据自身理解所产生的预期不一致, 进而导致原有的理解被破坏的状态(Proulx & Inzlicht, 2012)。在新模型中, 威胁与诱因两种刺激均可以诱发意义违反。与个体目前稳定的意义体验水平相比, 威胁刺激会导致意义体验下降, 而诱因使得个体意识到更强意义体验的存在, 导致意义体验的不平衡状态, 进而驱动意义寻求动机。意义维持模型认为, 在意义遭到破坏后, 可以通过同化(Assimilation)、顺应(Accommodation)、肯定(Affirmation)、抽象化(Abstraction)和重组(Assembly)来修复。同化是通过对违反意义的事件进行重新解释、修饰, 使其符合现有的意义系统; 顺应则是指调整现有的意义系统, 使得意义违反事件可以被合理解释。肯定策略是一种补偿策略, 指的是在意义违反后, 个体会强化已经持有的意义系统, 更加肯定其正确性。恐惧管理研究发现, 死亡凸显(Mortality salience)会增加个体所持世界观的正确性判断。个体会更加追求公正、惩罚不道德的人(刘亚楠, 许燕, 于生凯, 2010)。抽象化策略指的是在意义违反后, 个体寻找或创造事物之间联系的能力增强。重组策略与顺应策略有相似之处, 指的是对现有意义系统进行大规模的结构调整以解释当前事件。不同的是, 顺应策略是对某个单一的关系表征做出调整, 而重组则涉及多个关系表征。也就是说, 重组策略对现有意义系统的调整更大一些(左世江等, 2016)。通过以上策略, 个体将受损的意义体验恢复到正常水平, 或者获得更高的意义体验。意义恢复后, 整体意义框架没有变化, 而新的意义体验会改变整体意义框架中的子成分。

新模型整合了缺失恢复观与生命肯定观两种观点, 可以推演出一系列假设, 其中多数假设已有实证研究支持, 部分假设尚需未来研究检验。假设一:创伤性事件将显著降低当前意义体验水平, 打破与原有特质意义感之间的平衡, 从而驱动个体寻求意义的动机。如前所述, 这一假设已有大量文献支持。例如, 存在低意义体验、高意义寻求个体(张姝玥, 许燕, 2012)、低意义体验与意义寻求正相关(Steger et al., 2008a)、情境性威胁(如社会排斥)增强意义寻求动机(Graeupner & Coman, 2017)均是有力证据。然而, 并非所有威胁情景均能启动意义寻求动机, Park和Baumeister (2017)发现, 一般压力事件并不能增强意义寻求动机, 何种负性事件足以驱动意义寻求, 是未来研究的重要课题; 假设二:当个体的意义渴求水平很低时, 低意义体验也无法启动意义寻求。意义渴求水平存在个体差异, 低渴求水平与低意义体验无法形成差值, 会导致意义寻求动机无法生成。在Dezutter等(2014)的聚类分析中, 确实存在低意义体验低意义寻求的个体。Schnell (2010)也有类似的观点, 意义寻求主要源起于意义危机, 而非意义缺乏; 假设三:即使个体体验到了高水平生命意义, 只要知觉到诱因存在, 意义寻求动机就会被激发。诱因提供了更高水平的意义, 进而形成了与当下体验的不平衡状态。需要指出的是, 我们认为诱因既可以是内生的, 也可以来自于外部环境。聚类分析发现存在高意义体验高意义寻求个体, 表明某些特质的个体能够自发地寻求更高水平的意义(Dezutter et al., 2014)。高认知需求、开放性、好奇等特质与此相关(Steger et al., 2008b)。外部诱因是否能情景性地提升意义寻求, 目前尚未发现相关研究, 留待未来检验; 假设四:如果没有诱因存在, 高意义体验者寻求意义的动机会降低。聚类分析揭示了高意义体验低意义寻求个体的存在。高认知闭合、教条主义与此相关(Steger et al., 2008b)。

4.2 更多衍生假设与相关实证研究

依据模型的基本观点, 我们推演出了一系列基本假设。近年来, 生命意义感的构成成分逐渐清晰, 使我们可以依据新模型衍生出更多具体假设。学者们普遍认为, 生命意义感由一致性(Coherence)、目的(Purpose)和重要性(Significance)三种成分构成。三种成分协同作用, 相互影响但又彼此不同。一致性、目的和重要性分别是意义感的认知成分、动机成分和情感成分。理解生活(一致性)是设定目标, 发现生活价值的必要条件, 但并非充分条件。同样, 目的与重要性也有所区别。目的与未来定向密切相关, 重要性评价则既可以来自过去经历、现在的感受, 也可以是未来目标。三者彼此具有一定的独立性(Martela & Steger, 2016; George & Park, 2016)。George和Park (2017)开发了三维度生命意义量表对此观点进行了检验, 结果显示, 三维度量表具有良好的结构效度与内部一致性信度, 对其他相关意义变量的预测效度也更加精确。同时, 一些研究也发现, 虽然三种成分相关密切, 但彼此具有独立性。一项纵向研究发现, 精神性可以预测其后的意义体验, 但目的的预测变量却是社会支持而非其它变量。基于以上研究, 我们推测意义寻求也应该包含三种彼此紧密相关又相互独立的元素:一致性寻求(Search for coherence)、目的寻求(Search for purpose)与重要性寻求(Search for significance)。另外, 上述模型假设在意义系统受到威胁或者诱因驱动两种条件下均可产生意义需求。受到威胁时, 意义体验下降, 被诱因驱动后, 意义体验获得情景性提升。根据意义需求产生条件不同(威胁vs诱因), 以及寻求的内容的不同(一致性寻求vs目的寻求vs重要性寻求), 可将寻求的条件分为六类:一致性受到威胁、一致性被诱因驱动、目的受到威胁、目的受到诱因驱动、重要性受到威胁、重要性被诱因驱动。

4.2.1 衍生假设一:一致性受到威胁或受新的意义系统冲击引发意义寻求

一致性, 又称为可理解性(Comprehesion, George & Park, 2016), 不是指理解生活中的具体事件, 而是主我对生活这一客体的解释和理解。当生活中发生的事件与整体意义框架中的信念系统不一致时, 对一致性的需求就产生了。

创伤性事件通常会威胁到个体的信念系统, 最有可能诱发意义寻求。911恐怖袭击两个月后, 有2/3的美国成年人报告自己正在寻求意义(Updegraff, Silver, & Holman, 2008)。Lepore与Kernan (2009)的研究发现, 在确诊乳腺癌1年后, 仅有14%的受访者报告自己从未寻求过意义。另外, 在家庭成员去世后, 有85%的个体会问“为什么是这样”, 或者”为什么这件事发生在我们身上” (Tolstikova, Fleming, & Chartier, 2005)。这些证据都表明重大创伤事件会诱发意义寻求, 这是因为对重大压力事件的情景评估与整体意义框架中的某些信念(如“世界是安全的”、“他人是友善的”)产生了矛盾。

引发一致性寻求的另一因素可能源自于个体已有的意义系统受到另一强势意义系统的诱导与冲击。文化适应现象为此提供了一个样例。文化可以界定为“任何一种可以满足个体或群体的心理需要而在某一群人中共享并延续的知识传统” (Chiu, Kwan, & Liou, 2013)。共享性(Sharedness)与传承性(Continuity)构成文化的两个基本特征。文化不仅表现为国家文化、民族文化, 也可以是商业、组织、阶层、政治、地域乃至学科文化等。文化实质上是一个意义网络(Web of meaning), 包含行为与道德规范、价值标准、信念、脚本、社会活动图式等内容, 能够促进群体适应特定的生态环境(Kitayama, Duffy, & Uchida, 2006)。不同文化包含不同的意义网络, 因此, 个体在暴露于另一文化时, 原有意义网络可能不再有效, 需要适应新的意义系统, 继而诱发意义寻求动机。就我们的知识而言, 目前还没有关于文化适应(Acculturation), 或者居所流动性(Residential mobility)与意义寻求两者关系的研究。Eggleston和Oishi (2013)做出了与本文一致的预测, 认为居所流动性会增加个体寻求意义的动机, 但这一假设还需未来实证研究检验。

4.2.2 衍生假设二:目的缺失或者受诱因驱动会诱发意义寻求

目的是生命意义感的重要组成元素。弗兰克尔在提出意义寻求概念之初, 只是将生命意义感界定为人们对自己生命中的目的、目标的认识和追求。一致性与重要性两种元素, 是近年来研究者对概念内涵扩展的结果。目的作为核心元素, 也能从生命意义感量表内容的演化中体现出来。Crumbaugh与Maholick (1964)基于Frankl生命意义感的内涵编制的第一个测量工具即是生活目的问卷(Purpose in life scale), 其后虽然研究者发展出一系列包含不同成分的测量工具, 然而无一例外都涵盖了对目的性的测量。目的缺乏引起意义寻求得到了不少实证研究支持。Schulenberg等(2014)发现, 知性目标寻求测验(SONG)中的存在性真空(Existential Vacuum)和意义的愿望(Will to Meaning)两个分量表显著正相关。在一项以大学生为被试历时一年三次测量的追踪研究中, 目的缺乏不仅正向预测当前意义寻求水平, 还可以预测4个月及1年后的寻求倾向(Negru-Subtirica, Pop, Luyckx, Dezutter, & Steger, 2016 )。

我们认为, 意义寻求不仅会在目的缺乏时启动, 也常常为个体意识到的更高人生目的所诱发。遗憾的是, 目前几乎没有研究直接检验目的性行为与意义寻求之间的关系。一项对社交焦虑患者的日记追踪研究发现, 个体的目的性活动可以显著改善其情绪症状、增强生命意义感与幸福感水平(Kashdan & McKnight, 2013 )。增加行为的目的性是提升生命意义感的有效方法。这项研究虽然没有考察意义寻求在其中的角色, 但我们推测其扮演着中介作用。依据本文提出的模型, 我们推测一切诱发个体寻求更高生活目的的刺激, 比如创业意向(简丹丹, 段锦云, 朱月龙, 2010)、敬畏情绪(董蕊, 彭凯平, 喻丰, 2013)等, 均可以诱发意义寻求动机。未来研究可以用实验检验这一假设。

4.2.3 衍生假设三:重要性缺失或者重要性诱因诱发意义寻求动机

重要性(Significance)是对生命的价值评价, 是生命意义感中的情感成分。目的与重要性紧密相关但又彼此不同。一方面, 目的是未来的有价值的目标, 因而目的性行为可以增强个体对生活重要性的感知。另一方面, 两者又分属不同的构念。目的只与未来有关, 而对生活重要性的评价可以来自过去经验、当前感受、或者是未来定向。

重要性缺失引发意义寻求得到了大量实证研究的支持。相关研究发现, 意义寻求与存在性真空显著正相关, 与自尊显著负相关(Schulenberg et al., 2014)。实验研究进一步佐证了两者之间的因果关系。例如, 一项研究发现, 社会排斥会极大削弱个体重要性感知, 引发意义寻求(Graeupner & Coman, 2017)。另外, 一项恐惧管理研究发现, 虽然死亡凸显(Mortality salience)下, 个体会通过坚守自己所持的世界观以达成意义维持, 但上述现象只发生于高自尊个体, 低自尊个体不会坚守自己的世界观, 而是增强意义寻求的动机(Juhl & Routledge, 2014)。这表明缺乏生命重要感的个体, 存在性忧虑足以启动意义寻求的进程。

重要性诱因的出现导致意义需求增加也是引发意义寻求的一大因素。就我们的知识而言, 目前还没有相关实证研究。我们只能从已有相关研究中进行推论。例如, 道德升华感(Moral elevation)的研究表明, 当个体目睹他人美德(Moral beauty)后, 会感到自己在情感上得到了升华、希望自己变得更好, 同时伴有胸口温暖、喉咙哽咽、流泪等生理反应(Haidt, 2003)。我们推测, 道德升华感同时启动了个体对更高、更具价值生活的寻求。 也就是说, 意义寻求在其中起到了中介作用。

5 未来研究展望

近20多年来, 生命意义研究逐渐成为西方心理学界热点之一。截止2017年底, 在Pcychoinfo数据库中, 标题包含Meaning in life的文献多达1142篇。然而与之形成对照的是, 学者们对意义寻求的关注似乎少了很多。同样在Pcychoinfo中, 包含Search for meaning 或Quest for meaning标题词的文献只有329篇。虽然从研究广度上看, 学者们已经开始探索何人、在何种条件下、为何以及如何寻求生命意义, 并且取得了一定的成果, 但研究深度仍有待挖掘。鉴于此, 本文提出了意义寻求的前置因素模型, 描述了意义寻求产生的各种条件。毋庸置疑, 这一模型虽然最大程度借鉴了已有实证研究成果, 但仍不免存在主观推测成分, 需大量实证研究检验。除此之外, 此领域仍有以下问题亟需解决:

5.1 迫切需要编制三维度意义寻求量表

近几年来, 三成分说逐渐得到学界认可, 生命意义感三因素量表也已开发出来(George & Park, 2017)。与生命意义感丰富的学术文献相比, 对意义寻求的研究较少, 专门开发的测量工具也不多。目前为止, 只有两个量表中包含了对意义寻求的测量。在知性目标追寻测验(SONG)中, 包含意义愿望(Will to Meaning)分量表, 用来测量对意义的寻求。该分量表包括8个项目, 如:“我希望将来有令人激动的事发生”, “我打算获取一些新的不一样的东西” (Schulenberg et al., 2014)。除此之外, Steger等(2006)编制的生命意义问卷(Meaning in life questionnaire), 也包括意义寻求分量表, 其项目如“我正在寻觅我人生的一个目的或使命”, “我正在寻找自己生活的意义”。两个意义寻求量表(尤其是后者)虽然得到较广泛的应用, 但测量均不够精细, 未能区分寻求内容的差异。事实上, 理解、目的与重要性寻求三者既相重叠, 又相区别(Park, 2010)。理解寻求通常发生在对情境事件的解释与整体意义框架中的信念产生严重冲突时, 或遭遇无法理解、让人迷惑或感觉神秘的现象时; 目的寻求多出现于人生目标缺失, 或面对一个令人激动的新目标时; 重要性寻求主要出现于个体无法发现其人生价值, 或者更有价值和吸引力的事物出现之时。因此, 开发三维度意义寻求量表成为当前意义寻求领域的主要任务。目前, 笔者及同事已经完成量表的初步编制工作, 希望能为该领域的深入研究提供工具。

5.2 理清意义渴求、意义寻求与意义凸显之间的关系

在意义寻求研究文献中, 研究者相继开发出了意义渴求、意义寻求和意义凸显量表, 三个量表测量的构念并不相同。意义渴求(Will for meaning)包含在知性目标追寻测验(SONG)中, 测量的是个体对新的、更令人激动事情的渴望。Schulenberg等发现, SONG的维度1 (“存在的真空”维度)分数与一般痛苦水平、抑郁水平和生命意义追寻水平(MLP-S)呈现显著的正相关, 与生命意义体验水平(MLQ-P)、生活满意度(SWLS)、生活目的量表(PIL)分数呈现显著负相关。但维度2 (“意义渴求”)与生活目的水平(PIL)、生命意义体验水平(MLQ-P)呈显著正相关(但相关值较低) (Schulenberg et al., 2014)。意义寻求(Search for meaning)测量的是个体寻求意义的动机, 包含在生命意义感量表(MLQ)中(Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler, 2006)。如前所述, 在美国被试群体中, 意义寻求动机与生命意义感、生活满意度、主观幸福感、积极情绪显著负相关, 与抑郁、自杀意向、焦虑等正相关(Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan, & Lorentz, 2008a)。意义凸显(Meaning salience)量表由Hooker等编制(Thoughts of Meaning Scale; TOMS), 包含10个项目, 测量一日内思考意义问题的频率。意义凸显与生命意义感、生活目的、心理幸福感、积极情绪、活力呈强的显著正相关(相关系数均在0.54~0.61之间), 与抑郁症状、负性情绪显著负相关(Hooker, Masters, & Park, 2018)。这些文献表明, 意义凸显、意义渴求与意义寻求测量的构念是不同的。依据我们提出的模型, 意义凸显测量的是日常生活中个体觉察到意义的频率, 频率越高, 表明目前生活与整体意义框架越契合, 身心机能也越健康。意义渴求测量的是对意义的需求程度, 由觉知到的情景意义与基线意义水平之间的不平衡导致。意义渴求与意义寻求并不能等同, 渴求虽然是寻求的前提, 但渴求不一定诱发寻求。我们推测, 在一致性和重要性维度上, 渴求会自动化激活一致性寻求, 表现为侵入性思维(Intrusive thoughts)间歇性进入意识领域。而在目的维度上, 渴求激活的是控制性加工, 启动自我调节过程, 个体在评估需要可以达成的概率基础上做出是否寻求的决定。未来研究可以探索上述假设的正确性。

5.3 进一步加强意义寻求前置因素的实验研究

横断调查研究为研究者认识意义寻求的本质提供了丰富的信息。然而, 这样的研究并不能确认因果关系。例如, 一个明确自己正在寻求生活目的的个体, 如果没有进一步透露其它信息, 我们将无从知道其是出于目标受挫, 还是受到了其它更强有力目标的吸引。因此, 为检验本文提出的模型, 需要更多的实验研究。已有实验研究提供了两种研究模式, 一是通过实验室操纵某一变量, 如社会排斥或死亡凸显, 诱发意义危机, 考察意义寻求倾向(Graeupner & Coman, 2017); 二是直接启动生活无意义感, 如通过阅读一篇描述生活无意义可言的文章启动无意义感, 继而测量意义寻求的变化(Taubman-Ben-Ari, 2011)。我们认为, 已有的实验研究为本模型提供了初步支持, 但大部分实验研究考察的均是意义危机诱发的意义寻求, 鲜有报告源于外部诱因的意义寻求的研究。未来研究应着重关注这些变量对意义寻求的影响。

5.4 深化对意义寻求判断影响因素的研究

问卷调查研究与实验室研究虽然同为研究意义寻求的方法, 但本质上, 两种方法测量的因变量并不相同。实验法通过操纵情景因素, 直接测量意义寻求的变化, 其测量内容为意义寻求本身, 而问卷研究中, 所测量的意义寻求并非此刻情景的寻求动机, 而是意义寻求判断, 即通过回答问卷中呈现的问题表现自己的寻求倾向。已有文献中, 对生命意义判断(Meaning in life judgement)的研究较多。生命意义判断是主观的、更依赖直觉(Hicks & King, 2009b)。个体判断生命意义感的主要依据是人际关系和积极情绪, 并且两者可以相互补偿(Hicks & King, 2009a)。就我们所知, 目前未有关注个体做出意义寻求判断的心理过程与影响因素的研究, 未来研究应该致力于揭示其中的机制与相关影响因素。

参考文献

生命意义感量表中文版在大学生群体中的信效度

DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2010.06.021

URL

[本文引用: 1]

目的:引入Steger等编制的生命意义感量表(the Meaning in Life Questionnaire,MLQ),检验其在中国大学生群体中应用的信度和效度.方法:方便选取北京大学学生307名,随机分为两部分,一部分 (n=150)进行探索性因素分析,另一部分(n=157)进行验证性因素分析.用社会期望量表(Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale,MCSD)、未来取向应对量表(Future-oriented Coping Inventory,FCI)、正性负性情绪量表(Positive and Negative Affect Scale,PANAS)、自评抑郁量表(Self-Rating Depression Scale,SDS)、自尊量表(Self-Esteem Scale,SES)、总体幸福感量表(General Well-Being Schedule,GWB)检验MLQ中文版的效标效度.结果:(1)探索性因子分析提取了2个因子,分别是生命意义感(MLQ-P)和寻求意义感 (MLQ-S),累计贡献率为57.22%,项目负荷在0.579~0.829之间.验证性因素分析检验了结构的有效性 (χ2=43.81,GFI=0.94,AGFI=0.90,NFI=0.93,CFI=0.97,IFI=0.97,RMSEA=0.066).(2) 总量表的Cronbach α系数为0.71,2个分量表的α系数分别为0.81和0.72.(3)MLQ-P与SES、GWB、正性情绪、预先应对、预防应对、MCSD呈正相关 (r=0.19~0.59,均P<0.01),而与SDS、负性情绪呈负相关(r=-0.50,-0.18,均P<0.01);MLQ-S与预先应对、预 防应对和正性情绪正相关(r=0.20,0.31,0.15,均P<0.01).结论:生命意义感量表中文版在大学生中的信、效度较好,但仍需扩大样本进 一步深入检验.

恐惧管理研究:新热点、质疑与争论

Terror management theory regards worldview, self-esteem and close relationship as the basic three defensive mechanisms of terror management. The author introduces some researches on these mechanisms first and then reviews several new interpretations on mortality salience effect from perspective of cognitive closure, meaning pursuit, offensive defense, coalitional and control motivation. After that, the author presents his own idea, which differentiates terror management strategy into two categories: approach and avoidance. The approach strategy aims to control the uncertain death and transcendent the inevitable demise, the avoidance strategy indicates that individuals react to the potential reminder of death negatively. Meanwhile, the author points that TMT probably misinterprets the function of the cultural worldview. Additionally, some recommendations on terror management research in china are proposed.

创业意向的构思测量、影响因素及理论模型

创业意向是指将创业者的注意力、精力和行为引向某个特定目标的一种心理状态,它是创业行为的最好预测指标。个人背号、人格特质和外界环境等都会影响创业意向。计划行为理论和创业事件模型是公认的两个创业意向理论框架。目前将创业意向作为因变量是主流研究,而作为自变量和控制变量则是未来研究趋势。

高中生生命意义寻求与生命意义体验的关系

目的:在高中生中探讨生命意义寻求和生命意义体验的关系.方法:采用生命意义问卷,对1659名高中生进 行横断研究,对84名高中生进行三次追踪测查.结果:同时测量的生命意义寻求和体验之间呈正相关,但是在控制干扰变量后,后测体验只受前测体验的影响,与 前测寻求没有关系,后测寻求只受前测寻求的影响,与前测体验也没关系.结论:生命意义寻求和体验具有较高的稳定性,两维度之间不相互影响,而是各自预测本 维度的发展.

生命意义感获取的心理机制及其影响因素

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2017.01003

URL

[本文引用: 2]

生命意义感体验对个体身心健康有重要的影响,其相关研究也已开始受到心理学各个领域的广泛关注。生命意义感获得与维持的理论研究主要是包括意义感层次模型、意义感构建模型及意义感维持与流动模型。大五人格、心理模拟、积极/消极情绪和亲社会行为是影响个体生命意义感体验的主要因素。未来研究要进一步探讨生命意义感产生的影响因素,完善相关的理论模型,并要从时间序列的角度探讨意义感的产生过程,并对生命意义感获得及维持的跨文化差异进行探讨。

意义维持模型:理论发展与研究挑战

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2016.00101

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Meaning Maintenance Model (MMM) is a well-received social psychology theory in recent years, which claims meaning maintenance to be human most fundamental social motivation. Meaning violations evoke an aversive arousal, and relieving this feeling provides power to meaning maintenance which motivates compensation efforts to restore the meaning system. In a sense, MMM integrates theories like cognitive dissonance theory and has high explanation strengths. The process of meaning maintenance, including meaning violation, aversive arousal and compensation behavior, is well corroborated by expanded theoretical discussions and a large body of empirical studies. Nevertheless, there are certain problems of MMM, like vague conceptions, inadequate evidence for aversive arousal as a mediator and an alternative explanation of priming against compensation et al. Future researches should test the process of meaning maintenance. Besides, researches can focus the operation of compensation behavior and a positive process of meaning maintenance.

Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content

DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.120.3.338

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Goals and related constructs are ubiquitous in psychological research and span the history of psychology. Research on goals has accumulated sporadically through research programs in cognition, personality, and motivation. Goals are defined as internal representations of desired states. In this article, the authors review the theoretical development of the structure and properties of goals, goal establishment and striving processes, and goal-content taxonomies. They discuss affect as antecedent, consequence, and content of goals and argue for integrating across psychological content areas to study goal-directed cognition and action more efficiently. They emphasize the structural and dynamic aspects of pursuing multiple goals, parallel processing, and the parsimony provided by the goal construct. Finally, they advocate construct validation of a taxonomy of goals.

Do attachment styles affect the presence and search for meaning in life?

DOI:10.1007/s10902-013-9462-7

URL

[本文引用: 2]

The current work examines the connection between attachment theory and meaning in life (MIL) across adulthood, by inspecting attachment style differences on two dimensions of MIL: presence of meaning (PML) and search for meaning (SML). MIL and attachment measures were collected from 992 participants of three age-groups, young adults (21–30), established adults (31–49), and older adults (50–65). Multivariate analyses demonstrated that older adults scored higher on PML, while younger adults reported more SML. In general, securely attached individuals demonstrated more PML and less SML than participants with insecure attachment styles, and individuals with a fearful attachment style displayed more SML than other attachment styles. Age interacted with attachment, as dismissive young adults displayed less SML, and gender differences were revealed in PML among established adults with regard to the preoccupied and fearful attachment styles. Finally, a three-way interaction of attachment02×02age02×02gender was found for PML, as in the established adults, both preoccupied men and fearful women reported a decline in PML, while older women with secure attachment reported higher levels of PML. While in accordance with the developing literature in the field of positive psychology, the current findings shed light on the manner by which the connections between attachment styles, age and gender are associated with the presence and the search for MIL.

Culturally motivated challenges to innovations in integrative

research: Theory and solutions.Social Issues and Policy Review

An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis

Flow: The psychology of optimal experience

The undoing of traumatic life events

Meaning in life in emerging adulthood: A person-oriented approach

DOI:10.1111/jopy.12033

URL

PMID:23437779

[本文引用: 4]

The present study investigated naturally occurring profiles based on two dimensions of meaning in life: Presence of Meaning and Search for Meaning. Cluster analysis was used to examine meaning-in-life profiles, and subsequent analyses identified different patterns in psychosocial functioning for each profile. A sample of 8,492 American emerging adults (72.5% women) from 30 colleges and universities completed measures on meaning in life, and positive and negative psychosocial functioning. Results provided support for five meaningful yet distinguishable profiles. A strong generalizability of the cluster solution was found across age, and partial generalizability was found across gender and ethnicity. Furthermore, the five profiles showed specific patterns in relation to positive and negative psychosocial functioning. Specifically, respondents with profiles high on Presence of Meaning showed the most adaptive psychosocial functioning, whereas respondents with profiles where meaning was largely absent showed maladaptive psychosocial functioning. The present study provided additional evidence for prior research concerning the complex relationship between Presence of Meaning and Search for Meaning, and their relation with psychosocial functioning. Our results offer a partial clarification of the nature of the Search for Meaning process by distinguishing between adaptive and maladaptive searching for meaning in life.

Is happiness a moving target? The relationship between residential mobility and meaning in life

In J. A. Hicks & C. Routledge (eds.),

DOI:10.1007/978-94-007-6527-6_25

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Despite a long tradition of residential mobility in the United States and a growing trend of international mobility, the impact of frequent moving has only recently become a topic of scientific inquir

Personal goals, life meaning, and virtue: Wellsprings of a positive life

In C. Keyes, & J. Haidt (Eds.),

DOI:10.1037/10594-005

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Nothing is so insufferable to man as to be completely at rest, without passions, without business, without diversion, without effort. Then he feels his nothingness, his forlornness, his insufficiency, his weakness, his emptiness. (Pascal, The Pensees, 1660/1950, p. 57). As far as we know humans are the only meaning-seeking species on the planet. Meaning-making is an activity that is distinctly human, a function of how the human brain is organized. The many ways in which humans conceptualize, create, and search for meaning has become a recent focus of behavioral science research on quality of life and subjective well-being. This chapter will review the recent literature on meaning-making in the context of personal goals and life purpose. My intention will be to document how meaningful living, expressed as the pursuit of personally significant goals, contributes to positive experience and to a positive life. THE CENTRALITY OF GOALS IN HUMAN FUNCTIONING Since the mid-1980s, considerable progress has been made in under-standing how goals contribute to long-term levels of well-being. Goals have been identified as key integrative and analytic units in the study of human Preparation of this chapter was supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. I would like to express my gratitude to Corey Lee Keyes and Jon Haidt for the helpful comments on an earlier draft of this chapter.

Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy

Meaning in life as comprehension, purpose, and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions

DOI:10.1037/gpr0000077

URL

[本文引用: 4]

Abstract To advance meaning in life (MIL) research, it is crucial to integrate it with the broader meaning literature, which includes important additional concepts (e.g., meaning frameworks) and principles (e.g., terror management). A tripartite view, which conceptualizes MIL as consisting of 3 subconstructs—comprehension, purpose, and mattering—may facilitate such integration. Here, we outline how a tripartite view may relate to key concepts from within MIL research (e.g., MIL judgments and feelings) and within the broader meaning research (e.g., meaning frameworks, meaning making). On the basis of this framework, we review the broader meaning literature to derive a theoretical context within which to understand and conduct further research on comprehension, purpose, and mattering. We highlight how future research may examine the interrelationships among the 3 MIL subconstructs, MIL judgments and feelings, and meaning frameworks.

The multidimensional existential meaning scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life

DOI:10.1080/17439760.2016.1209546

URL

[本文引用: 3]

Abstract To address conceptual difficulties and advance research on meaning in life (MIL), it may be useful to adopt a tripartite view of meaning as consisting of comprehension, purpose, and mattering. This paper discusses the development of the Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale (MEMS), which explicitly assesses these three subconstructs. Results from three samples of undergraduates showed the MEMS to have favorable psychometric properties (e.g. good factor structure and reliability) and demonstrated that it can effectively differentiate the three subconstructs of meaning. Regression and relative importance analyses showed that each MEMS subscale carried predictive power for relevant variables and other meaning measures. Additionally, the MEMS subscales demonstrated theoretically consistent, differential associations with other variables (e.g. dogmatism, behavioral activation, and spirituality). Overall, results suggest that the MEMS may offer more conceptual precision than existing measures, and it may open new avenues of research and facilitate a more nuanced understanding of MIL.

The dark side of meaning-making: How social exclusion leads to superstitious thinking

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2016.10.003

URL

[本文引用: 4]

61Social exclusion leads to endorsement of superstitious and conspiratorial beliefs.61Search for meaning mediates between social exclusion and superstitious thinking.61Social inclusion could be used as a means of counteracting conspiratorial beliefs.

The moral emotions

In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldschmith (Eds.),

Life is pretty meaningful

Positive mood and social relatedness as information about meaning in life

DOI:10.1080/17439760903271108

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Meaning in life is widely considered a cornerstone of human functioning, but relatively little is known about the factors that influence judgments of meaning in life. Four studies examined positive affect (PA) and social relatedness as sources of information for meaning in life judgments. Study 1 (N = 150) showed that relatedness need satisfaction (RNS) and PA each shared strong independent links to meaning in life. In Study 2 (N = 63), loneliness moderated the effects of a positive mood induction on meaning in life ratings. In Study 3 (N = 65), priming positive social relationships reduced the contribution of PA to subsequent judgments of meaning in life. In Study 4 (N = 95), relationship primes decreased reliance on PA and increased reliance on RNS compared to dessert primes. Results are discussed in terms of the value of integrating judgment processes in studies of meaning in life.

Meaning in life as a subjective judgment and a lived experience

DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00193.x

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Meaning in life has long been recognized as a central dilemma of human life. In this article, we review some of the challenges of studying meaning in life from the perspective of social psychology. We draw on the diary of Etty Hillesum, a young woman who was killed in Auschwitz, to argue for the relevance of current empirical approaches to meaning in life. We review evidence suggesting that meaning in life is an important variable in the psychology of human functioning while also acknowledging that there is no consensus definition for the construct. Drawing on Hillesum's diary and our research, we argue for the importance of considering meaning in life as the outcome of a subjective judgment process. We then review research showing the strong relationship between positive mood and meaning in life and suggest that such a relationship is born out in the phenomenology of meaning in life.

A meaningful life is a healthy life: A conceptual model linking meaning and meaning salience to health

DOI:10.1037/gpr0000115

URL

[本文引用: 1]

react-text: 140 Introduction: People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) are more likely to smoke cigarettes than are individuals in the general population. The health implications of tobacco use are substantially more dire among PLWHA than among otherwise healthy smokers, including higher rates of various cancers, cardiovascular disease, inflammation, and lung infections. Efficacious behavioral and medication... /react-text react-text: 141 /react-text [Show full abstract]

The effects of trait self-esteem and death cognitions on worldview defense and search for meaning

DOI:10.1080/07481187.2012.718038

URL

PMID:24521047

[本文引用: 1]

Terror management theory asserts that attaining self-esteem by adhering to the standards of meaning-providing worldviews helps manage death concerns. Research has shown that mortality salience (MS) increases worldview defense, however, there are conflicting results concerning how trait self-esteem moderates this effect. Studies 1 and 2 demonstrated that MS increases worldview defense for high, but not low, trait self-esteem individuals. These studies raised the question as to whether those with low trait self-esteem engage in efforts to find meaning in response to MS. Study 3 showed that MS increased the search for meaning for low, but not high, trait self-esteem individuals.

Commitment to a purpose in life: An antidote to the suffering by individuals with social anxiety disorder

DOI:10.1037/a0033278

URL

PMID:4145806

[本文引用: 1]

Recent acceptance-and mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral interventions explicitly target the clarification and commitment to a purpose in life. Yet, scant empirical evidence exists on the value of purpose as a mechanism relevant to psychopathology or well-being. The present research explored daily (within-person) fluctuations in purposeful pursuits and well-being in a community sample of 84 adults with (n = 41) and without (n = 43) the generalized subtype of social anxiety disorder (SAD). After completing an idiographic measure of purpose in life, participants monitored their effort and progress toward this purpose, along with their well-being each day. Across 2 weeks of daily reports, we found that healthy controls reported increased self-esteem, meaning in life, positive emotions, and decreased negative emotions. People with SAD experienced substantial boosts in well-being indicators on days characterized by significant effort or progress toward their life purpose. We found no evidence for the reverse direction (with well-being boosting the amount of effort or progress that people with SAD devote to their purpose), and effects could not be attributed to comorbid mood or anxiety disorders. Results provide evidence for how commitment to a purpose in life enriches the daily existence of people with SAD. The current study supports principles that underlie what many clinicians are already doing with clients for SAD.

Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion

DOI:10.1080/02699930302297

URL

PMID:29715721

[本文引用: 1]

In this paper we present a prototype approach to awe. We suggest that two appraisals are central and are present in all clear cases of awe: perceived vastness, and a need for accommodation, defined as an inability to assimilate an experience into current mental structures. Five additional appraisals account for variation in the hedonic tone of awe experiences: threat, beauty, exceptional ability, virtue, and the supernatural. We derive this perspective from a review of what has been written about awe in religion, philosophy, sociology, and psychology, and then we apply this perspective to an analysis of awe and related states such as admiration, elevation, and the epiphanic experience.

Detecting and constructing meaning in life events

DOI:10.1080/17439760902992316

URL

Three studies examined the meaning ascribed to events varying in intensity and valence and how meaning detection and construction relate to the experience of meaning in life events. In Study 1, participants were more likely to expect meaning to emerge from major life events particularly if they are negative, while trivial events were expected to be meaningful if they were positive. Study 2 showed that constructed meaning was more likely to occur in response to negative events while detected meaning was more likely to be associated with positive events. Study 3 showed that this ‘match’ between valence and meaning strategy predicted enhanced experience of meaning in those events. These studies suggest that the more subtle experience of meaning detection may provide a way to understand the meaning that emerges from positive events and experiences.

Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life

Self as cultural mode of being. In: S. Kitayama, & D. Cohen (eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology

(pp.

The psychology of worldviews

DOI:10.1037/1089-2680.8.1.3

URL

[本文引用: 1]

A worldview (or “world view”) is a set of assumptions about physical and social reality that may have powerful effects on cognition and behavior. Lacking a comprehensive model or formal theory up to now, the construct has been underused. This article advances theory by addressing these gaps. Worldview is defined. Major approaches to worldview are critically reviewed. Lines of evidence are described regarding worldview as a justifiable construct in psychology. Worldviews are distinguished from schemas. A collated model of a worldview's component dimensions is described. An integrated theory of worldview function is outlined, relating worldview to personality traits, motivation, affect, cognition, behavior, and culture. A worldview research agenda is outlined for personality and social psychology (including positive and peace psychology).

Searching for and making meaning after breast cancer: Prevalence, patterns, and negative affect

DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.038

URL

PMID:19157667

[本文引用: 1]

This study describes the prevalence and patterns of searching for meaning in the aftermath of breast cancer and asks how the search relates to made meaning and emotional adjustment. Women ( = 72) reported their level of searching for meaning, made meaning and negative affect at multiple time points in the first 18 months after breast cancer treatment. Over time, four search for meaning patterns emerged: continuous (44%), exiguous (28%), delayed (15%) and resolved (13%). Just over half of the participants reported having made meaning at early and late time points. A higher level of searching for meaning was unrelated to made meaning, but was associated with a higher level of negative affect in longitudinal analyses controlling for baseline levels. Women who engaged in an ongoing, unresolved search for meaning from baseline to follow-up also had a significantly higher level of negative affect at follow-up than women who infrequently or never engaged in a search for meaning over time. These analyses reveal that: a) there is great variability in the prevalence and pattern of searching for meaning in the aftermath of breast cancer, and b) searching for meaning may be both futile and distressing.

Sensation’s ghost: The non-sensory “fringe” of consciousness

The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance

DOI:10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623

URL

[本文引用: 3]

Despite growing interest in meaning in life, many have voiced their concern over the conceptual refinement of the construct itself. Researchers seem to have two main ways to understand what meaning in life means: coherence and purpose, with a third way, significance, gaining increasing attention. Coherence means a sense of comprehensibility and one's life making sense. Purpose means a sense of core goals, aims, and direction in life. Significance is about a sense of life's inherent value and having a life worth living. Although some researchers have already noted this trichotomy, the present article provides the first comprehensible theoretical overview that aims to define and pinpoint the differences and connections between these three facets of meaning. By arguing that the time is ripe to move from indiscriminate understanding of meaning into looking at these three facets separately, the article points toward a new future for research on meaning in life.

The meaningful identity: A longitudinal look at the interplay between identity and meaning in life in adolescence

DOI:10.1037/dev0000176

URL

PMID:27598255

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Identity formation in adolescence is closely linked to searching for and acquiring meaning in one's life. To date little is known about the manner in which these 2 constructs may be related in this developmental stage. In order to shed more light on their longitudinal links, we conducted a 3-wave longitudinal study, investigating how identity processes and meaning in life dimensions are interconnected across time, testing the moderating effects of gender and age. Participants were 1,062 adolescents (59.4% female), who filled in measures of identity and meaning in life at 3 measurement waves during 1 school year. Cross-lagged models highlighted positive reciprocal associations between (a) commitment processes and presence of meaning and (b) exploration processes and search for meaning. These results were not moderated by adolescents' gender or age. Strong identification with present commitments and reduced ruminative exploration helped adolescents in having a clear sense of meaning in their lives. We also highlighted the dual nature of search for meaning. This dimension was sustained by exploration in breadth and ruminative exploration, and it positively predicted all exploration processes. We clarified the potential for a strong sense of meaning to support identity commitments and that the process of seeking life meaning sustains identity exploration across time. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2016 APA, all rights reserved).

Making sense of the meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events

DOI:10.1037/a0018301

URL

PMID:20192563

[本文引用: 2]

Interest in meaning and meaning making in the context of stressful life events continues to grow, but research is hampered by conceptual and methodological limitations. Drawing on current theories, the author first presents an integrated model of meaning making. This model distinguishes between the constructs of global and situational meaning and between "meaning-making efforts" and "meaning made," and it elaborates subconstructs within these constructs. Using this model, the author reviews the empirical research regarding meaning in the context of adjustment to stressful events, outlining what has been established to date and evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of current empirical work. Results suggest that theory on meaning and meaning making has developed apace, but empirical research has failed to keep up with these developments, creating a significant gap between the rich but abstract theories and empirical tests of them. Given current empirical findings, some aspects of the meaning-making model appear to be well supported but others are not, and the quality of meaning-making efforts and meanings made may be at least as important as their quantity. This article concludes with specific suggestions for future research.

Meaning in life and adjustment to daily stressors

DOI:10.1080/17439760.2016.1209542

URL

[本文引用: 2]

People perceive their life as meaningful when they find coherence in the environment. Given that meaning of life is tied to making sense of life events, people who lack meaning would be more threatened by stressful life events than those with a strong sense of meaning in life. Four studies demonstrated links between perceptions of life meaningfulness and perceived levels of stress. In Study 1, participants with lower levels of meaning in life reported greater stress than those who reported higher meaning in life. In Study 2 and Study 3, participants whose meaning in life had been threatened experienced greater stress than those whose meaning in life had been left intact. In Study 4, anticipation of future stress caused participants to rate themselves higher on the quest for meaning in life. These findings suggest that perceiving life as meaningful functions as a buffer against stressors.

Assessing meaning and meaning making in the context of stressful life events: Measurement tools and approaches

DOI:10.1080/17439760.2013.830762

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Theory and research on meaning has proliferated in recent years, focusing on both global meaning and processes of making meaning from difficult life events such as trauma and serious illness. However, the measurement of meaning constructs lags behind theoretical conceptualizations, hindering empirical progress. In this paper, we first delineate a meaning-making framework that integrates current theorizing about meaning and meaning making. From the vantage of this framework, we then describe and evaluate current approaches to assessing meaning-related phenomena, including global meaning and situational meaning constructs. We conclude with suggestions for an integrative approach to assessing meaning-related constructs in future research.

The five “A” s of meaning maintenance: Finding meaning in the theories of sense making

DOI:10.1080/1047840X.2012.702372

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Across eras and literatures, multiple theories have converged on a broad psychological phenomenon: the common compensation behaviors that follow from violations of our committed understandings. The meaning maintenance model (MMM) offers an integrated account of these behaviors, as well as the overlapping perspectives that address specific aspects of this inconsistency compensation process. According to the MMM, all meaning violations may bottleneck at neurocognitive and psychophysiological systems that detect and react to the experience of inconsistency, which in turn motivates compensatory behaviors. From this perspective, compensation behaviors are understood as palliative efforts to relieve the aversive arousal that follows from any experience that is inconsistent with expected relationships hether the meaning violation involves a perceptual anomaly or an awareness of a finite human existence. In what follows, we summarize these efforts, the assimilation, accommodation, affirmation, abstraction and assembly behaviors that variously manifest in every corner of our discipline, and academics, more generally.

Understanding all inconsistency compensation as a palliative response to violated expectations

DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2012.04.002

URL

PMID:22516239

[本文引用: 1]

It has been repeatedly shown that, when people have experiences that are inconsistent with their expectations, they engage in a variety of compensatory efforts. Although there have been many superficially different accounts for these behaviors, a potentially unifying inconsistency compensation perspective is currently coalescing. Following from a common prediction error/conflict monitoring mechanism, any given inconsistency is understood as evoking a common syndrome of aversive arousal. In turn, this aversive arousal is understood to motivate palliative efforts, which manifest as the analogous compensation behaviors reported within different psychological literatures. Based on this perspective, compensation efforts following both ‘high-level’ (e.g., attitudinal dissonance) and ‘low-level’ (e.g., Stroop task color/word mismatches) inconsistencies can now be understood in terms of a common motivational account.

Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation,development, and well-being

.

Existential indifference: Another quality of meaning in life

Measuring search for meaning: A factor-analytic evaluation of the Seeking of Noetic Goals Test (SONG)

DOI:10.1007/s10902-013-9446-7

URL

[本文引用: 5]

This study’s primary purpose was to examine the factor structure of the 20-item Seeking of Noetic Goals (SONG) test via exploratory and confirmatory factor-analytic procedures. An additional objective was to report on the measure’s incremental validity in comparison to the Search scale of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ), an alternative measure of search for meaning. This study utilized data from three samples of American undergraduates ( N 02=02908) from a medium-sized southern university. Factor analysis supported a two-factor model of the SONG, with patterns of correlation further suggesting the measure assesses distinct constructs. Multi-group confirmatory factor analysis indicated similar scale structure and item answering in terms of gender. Overall, the first factor yielded reliable scores that correlated significantly and in the expected direction with measures of well-being and psychological distress. The second factor did not yield reliable scores nor did it correlate significantly with many of the other measures administered. However, both factors were shown to significantly predict scores from measures of depression and general psychological distress after controlling for MLQ Search scale scores. We consider the data with respect to SONG scoring and interpretation, and discuss implications of these data for future research.

Grief and the search for meaning: Exploring the assumptive worlds of bereaved college students

DOI:10.1521/jscp.1991.10.3.270

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Researchers have recently begun to challenge long-standing views of grief and have called for new approaches to help understand the phenomenon. In this vein, the present study examined the impact of bereavement on people's basic assumptions about themselves and their world. Three categories of assumptions were explored: Benevolence of the World, Meaningfulness of the World, and Self-Worth. Twenty-one undergraduates who had recently lost a parent and 21 matched controls were compared on a series of objective measures; in addition, the bereaved sample also participated in lengthy semistructured clinical interviews. Assumptions about meaning emerged as an important variable, both in distinguishing between the bereaved and control samples and also in accounting for differences in the grief responses of the bereaved. Compared with matched controls, the bereaved subjects were significantly less likely to believe in a meaningful world. Further, within the bereaved sample, the greater the subjects' ability to fin...

Wrestling with our better selves: The search for meaning in life

In K. D. Markman, T. Proulx, & M. J. Lindberg (Eds.),

DOI:10.1037/14040-011

URL

[本文引用: 4]

How would you know if you found something if you never have been looking for it? Why would you look for something you already have? Questions such as these capture the two poles that psychological ideas about meaning in life have been drawn to over the past century or so. One idea about meaning in life blends the effort with the outcome, mingling seeking and finding, pursuing and experiencing. The search for meaning and the presence of meaning whirl around each other in the uniquely human navigation of existential tides. The other idea about meaning in life separates the two, as if seeking meaning was like eating and experiencing meaning was like the rest of life. Most of the time, people are satiated, content, full enough of meaning that it is out of their awareness. On the one hand, the process of seeking meaning is the structure of experiencing meaning. On the other hand, we seek only when we hunger and our previous stores of meaning have been depleted. The search for meaning straddles this duality. It is easy to see it as a natural, ongoing mental process. We make meaning all of the time. It is also easy to see it as a process that normally slumbers, waiting for when it is needed. We appreciate homeostasis. This chapter explores the dual nature of the search for meaning in life and examines some of the research that supports this perspective. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2015 APA, all rights reserved)

The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life

DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Counseling psychologists often work with clients to increase their well-being as well as to decrease their distress. One important aspect of well-being, highlighted particularly in humanistic theories of the counseling process, is perceived meaning in life. However, poor measurement has hampered research on meaning in life. In 3 studies, evidence is provided for the internal consistency, temporal stability, factor structure, and validity of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ), a new 10-item measure of the presence of, and the search for, meaning in life. A multitrait-multimethod matrix demonstrates the convergent and discriminant validity of the MLQ subscales across time and informants, in comparison with 2 other meaning scales. The MLQ offers several improvements over current meaning in life measures, including no item overlap with distress measures, a stable factor structure, better discriminant validity, a briefer format, and the ability to measure the search for meaning.

Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year

DOI:10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Meaning in life and life satisfaction are both important variables in well-being research. Whereas an appreciable body of work suggests that life satisfaction is fairly stable over long periods of time, little research has investigated the stability of meaning in life ratings. In addition, it is unknown whether these highly correlated variables change independent of each other over time. Eighty-two participants (mean age02=0219.302years, SD 1.4; 76% female; 84% European-American) completed measures of the presence of meaning in life, the search for meaning in life, and life satisfaction an average of 1302months apart (SD02=022.302months). Moderate stability was found for presence of meaning in life, search for meaning in life, and life satisfaction. Multiple regressions demonstrated specificity in predicting change among these measures. Support for validity and reliability of these variables is discussed.

The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life

DOI:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Counseling psychologists often work with clients to increase their well-being as well as to decrease their distress. One important aspect of well-being, highlighted particularly in humanistic theories of the counseling process, is perceived meaning in life. However, poor measurement has hampered research on meaning in life. In 3 studies, evidence is provided for the internal consistency, temporal stability, factor structure, and validity of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ), a new 10-item measure of the presence of, and the search for, meaning in life. A multitrait-multimethod matrix demonstrates the convergent and discriminant validity of the MLQ subscales across time and informants, in comparison with 2 other meaning scales. The MLQ offers several improvements over current meaning in life measures, including no item overlap with distress measures, a stable factor structure, better discriminant validity, a briefer format, and the ability to measure the search for meaning.

Understanding the search for meaning in life: personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x

URL

PMID:18331281

[本文引用: 5]

ABSTRACT Although several theories assert that understanding the search for meaning in life is important, empirical research on this construct is sparse. Three studies provide the first extensive effort to understand the correlates of the search for meaning in a multistudy research program. Assessed were relations between search for meaning and well-being, cognitive style, and the Big Five, Big Three, Approach/Avoidance, and Interest models of personality, with a particular emphasis on understanding the correlates of search for meaning that are independent of presence of meaning. Conceptual models of the relation between search and presence were tested. Findings suggest that people lacking meaning search for it; the search for meaning did not appear to lead to its presence. Study 3 found that basic motive dispositions moderated relations between search for meaning and its presence. Results highlight the importance of basic personality dispositions in understanding the search for meaning and its correlates.

The meaningful life in Japan and the United States: Levels and correlates of meaning in life

DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2007.09.003

URL

[本文引用: 6]

Culture supplies people with the provisions to derive meaning from life. However, no research has examined cultural variation in the two principal dimensions of meaning in life, presence of meaning and search for meaning. The present investigation adapted theories of self-concept and cognitive styles to develop a dialectical model of meaning in life, which predicted cultural differences in the tendency to experience search for meaning as opposed to, or harmonious with, presence of meaning. Using data from American (02=021183) and Japanese (02=02982) young adults, mean levels and correlates of presence of meaning and search for meaning were examined. As predicted, Americans reported greater presence of meaning; Japanese reported greater search for meaning. In accordance with the model, search for meaning was negatively related to presence of meaning and well-being in the United States (opposed) and positively related to these variables in Japan (harmonious). Thus, the search for meaning appears to be influenced by culture, and search for meaning appears to moderate cultural influences on presence of meaning.

Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood

DOI:10.1080/17439760802303127

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Meaning in life is thought to be important to well-being throughout the human life span. We assessed the structure, levels, and correlates of the presence of meaning in life, and the search for meaning, within four life stage groups: emerging adulthood, young adulthood, middle-age adulthood, and older adulthood. Results from a sample of Internet users (N = 8756) demonstrated the structural invariance of the meaning measure used across life stages. Those at later life stages generally reported a greater presence of meaning in their lives, whereas those at earlier life stages reported higher levels of searching for meaning. Correlations revealed that the presence of meaning has similar relations to well-being across life stages, whereas searching for meaning is more strongly associated with well-being deficits at later life stages.

Is the meaning of life also the meaning of death? A terror management perspective reply

DOI:10.1007/s10902-010-9201-2

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The human quality of self-awareness makes individuals aware of their inventible death. How does this knowledge influence meaning in life and is influenced by it? Four studies examined the association between meaning in life and awareness of death, through a Terror Management Theory perspective. Study 1 assessed the effects of a mortality reminder on self-reports of meaning in life, while exploring the moderating role of self-esteem. The findings indicate a trend in which after a mortality salience induction, high self-esteem individuals tend to view their lives as more meaningful. Studies 2 and 3 examined the effect of thinking about the meaning of life on death-thought accessibility, and found it to be higher in both the mortality and meaning salience conditions, as compared to a control condition. Study 4 sought to discover whether reminders of one’s meaning in life would yield cultural worldview validation, and indeed revealed a more severe perception of social transgressions following both mortality and meaning salience. Findings highlight the understanding that meaning in life is a basic existential concept closely related to awareness of death’s inevitability.

Adjustment to threatening events :A theory of cognitive adaptation

DOI:10.1037/0003-066X.38.11.1161

URL

[本文引用: 1]

ABSTRACT Proposes a theory of cognitive adaptation to threatening events. It is argued that the adjustment process centers around 3 themes: A search for meaning in the experience, an attempt to regain mastery over the event in particular and over life more generally, and an effort to restore self-esteem through self-enhancing evaluations. These themes are discussed with reference to cancer patients' coping efforts. It is maintained that successful adjustment depends, in a large part, on the ability to sustain and modify illusions that buffer not only against present threats but also against possible future setbacks. (84 ref) (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)

Grief, complicated grief, and trauma: The role of the search for meaning, impaired self-reference, and death anxiety

The search for meaning following a stroke

DOI:10.1207/s15324834basp1201_6

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Predictions from cognitive theories of adjustment to victimization were tested in two groups: stroke patients and their caregivers. Consistent with these approaches, a substantial proportion of respondents reported searching for a cause, asking themselves "Why me?" and finding meaning in the event. Multiple regression analysis revealed that, even when the effects of the severity of the stroke were controlled for, finding meaning had the positive effects proposed by a cognitive approach. A concern with the selective incidence of the event was associated with poorer adjustment, but being able to identify a cause was related to more positive outcomes. Those who held themselves responsible for the stroke were more poorly adjusted when the effects of severity of the stroke were controlled for. The results suggest that future researchers make a careful distinction between causal attributions for a negative event, selective incidence attributions ("Why me?"), and responsibility attributions. They appear to have different implications for adjustment following a traumatic event.

Searching for and finding meaning in collective trauma: Results from a national longitudinal study of the 9/11 terrorist attacks

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.709

URL

PMID:18729704

[本文引用: 1]

The ability to make sense of events in one's life has held a central role in theories of adaptation to adversity. However, there are few rigorous studies on the role of meaning in adjustment, and those that have been conducted have focused predominantly on direct personal trauma. The authors examined the predictors and long-term consequences of Americans' searching for and finding meaning in a widespread cultural upheaval-the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001-among a national probability sample of U.S. adults (N = 931). Searching for meaning at 2 months post-9/11 was predicted by demographics and high acute stress response. In contrast, finding meaning was predicted primarily by demographics and specific early coping strategies. Whereas searching for meaning predicted greater posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptoms across the following 2 years, finding meaning predicted lower PTS symptoms, even after controlling for pre-9/11 mental health, exposure to 9/11, and acute stress response. Mediation analyses suggest that finding meaning supported adjustment by reducing fears of future terrorism. Results highlight the role of meaning in adjustment following collective traumas that shatter people's fundamental assumptions about security and invulnerability. 2008 American Psychological Association.

Attachment and meaning-making in perinatal bereavement

DOI:10.1080/074811802753594682

URL

PMID:11980450

[本文引用: 1]

The study examined the psychological impact of perinatal bereavement on 108 women, from a dual attachment and meaning-making perspective, both descriptively and predictively. The study hypothesized that grief acuity is a function of both attachment security (operationalized by A. Antonovsky's 1979 Sense of Coherence [SOC] scale), and the ongoing search for meaning. Controlling for time post-loss, psychological distress and intrusive thoughts; sense of coherence and search for meaning significantly predicted current grief acuity. The findings supported the conceptualization of grief as an interpretive phenomenon, elicited by the loss of a primary attachment figure, thereby shattering core life purposes, and implicating the need to reinstate meaning.

What do people think they’re doing? Action identification and human behavior

The dynamics of death and meaning: the effects of death-relevant cognitions and personal need for structure on perceptions of meaning in life

Viktor frankl’s meaning-seeking model and positive psychology

In A. Batthyany & P. Russo-Netzer (Eds.),

DOI:10.1007/978-1-4939-0308-5_10

URL

[本文引用: 3]

The main purpose of this chapter is to introduce Viktor Frankl logotherapy to the twenty-first century, especially to positive psychologists interested in meaning research and applications. Frankl radically positive message of re-humanizing psychotherapy is much needed in the current technological culture. More specifically, I explain the basic assumptions of logotherapy and translate them into a testable meaning-seeking model to facilitate meaning research and intervention. This model consists of five hypotheses: (1) The Self-Transcendence Hypothesis: The will to meaning is a spiritual and primary motivation for self-transcendence; thus, it predicts that spiritual pathways (e.g., spiritual care, self-transcendence) will enhance meaning in life and well-being, even when other pathways to well-being are not available. (2) The Ultimate Meaning Hypothesis: It predicts that belief in the intrinsic meaning and value of life, regardless of circumstances, is more functional than alternative global beliefs. It also predicts that belief in ultimate meaning facilitates the discovery of meaning of the moment. (3) The Meaning Mindset Hypothesis: A meaning mindset, as compared to the success mindset, leads to greater meaningfulness, compassion, moral excellence, eudaemonic happiness, and resilience. (4) The Freedom of Will Hypothesis: People who believe in the inherent human capacity for freedom and responsibility, regardless of circumstances, will show higher autonomy and authenticity than those without such beliefs. (5) The Value Hypothesis of Discovering Meaning: Meaning is more likely to be discovered through creative, experiential, and attitudinal values that are motivated by self-transcendence rather than by self-interest. Together, they capture the complexity and centrality of meaning seeking in healing and well-being. In sum, Viktor Frankl emphasizes the need for a radical shift from self-focus to meaning-focus as the most promising way to lift up individuals from the dark pit of despair to a higher ground of flourishing. This chapter outlines the differences between logotherapy and positive psychology and suggests future research to bridge these two parallel fields of study for the benefit of psychology and society.