1 引言

自恋是一个历久弥新的主题, 因其丰富的内涵及其与日常生活的联系, 一直备受学界和大众关注(Campbell & Crist, 2020; Sedikides, 2021; 余震坤 等, 2019)。随着自恋领域研究的扩展和深入, 不但研究者们已经逐步区分出了自大型自恋(grandiose narcissism)与脆弱型自恋(vulnerable narcissism) (如Miller et al., 2011)、能动型自恋(agentic narcissism)与共生型自恋(communal narcissism) (Gebauer et al., 2012)、钦佩型自恋(admirative narcissism)与竞争型自恋(rivalrous narcissism) (Back et al., 2013)等自恋的表现型; 还有许多研究者将目光转向了自恋在群体水平上的表达, 也就是集体自恋(collective narcissism), 并开始致力于探究集体自恋及其在群际水平上的影响, 尤其是它对群际冲突的影响或催化促进作用(如Cichocka, 2016; Golec de Zavala et al., 2009)。目前, 集体自恋在国外主要受到人格心理学、社会心理学、政治心理学等领域学者的积极关注(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019), 国内仅有少数学者开展过相关研究(如Cai & Gries, 2013; Wang et al., 2021)。鉴于集体自恋的理论意义以及它在理解当今世界重要社会问题上具有的现实意义(Cichocka & Cislak, 2020; Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2021), 而国内学界暂无专文探讨此概念, 故本文将先对集体自恋及现有研究作一介绍和梳理, 进而再对该领域研究不足之处展开反思, 并对未来研究予以展望, 以期推动集体自恋的本土乃至跨文化研究。

需要说明的是, 该领域的开创者们(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009)在集体自恋的概念界定和量表编制上都充分参考了个体自恋的内涵和量表, 而且研究者们在研究假设和方法上也可能较多地借鉴了个体自恋领域的成果(Cichocka & Cislak, 2020; Golec de Zavala, 2011), 那么可以预见, 集体自恋与个体自恋在概念和研究上都可能有些类似之处。尽管如此, 集体自恋是一个相对独立于个体自恋的构念(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019), 它主要预测群际态度和行为(而个体自恋往往无法预测这些群际态度和行为), 并且它还具有许多独有的特征或效应(Golec de Zavala, 2018, 2019)。当前, 集体自恋已经形成了自己专属的研究领地。鉴于此, 下文对集体自恋概念及研究的介绍将不涉足个体自恋领域; 但考虑到两个领域的潜在联系, 在随后的现有研究不足及展望部分, 本文将部分地结合个体自恋领域的最新进展(如Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Miller et al., 2021)来对集体自恋领域的研究展开反思和讨论。

2 集体自恋的概念及渊源

2.1 集体自恋的内涵界定

集体自恋目前被定义为一种对于“自身所属群体是卓越的并值得优待, 却未充分被他者承认1(1 承认(recognition)是西方观念史上的一个重要术语, 在不同思想家眼中含有或积极或消极的意义(Honneth, 2018/2020)。根据著名学者福山的看法, 对身份获得承认的需要是一个统合了当今世界舞台上众多现象的主要概念(Fukuyama, 2018)。)”的信念(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019), 或者一种展现了自大(grandiose)、夸大(inflated)的内群体形象的态度取向, 而这种形象又依赖于外界对内群体价值的承认(Cichocka & Cislak, 2020)。简单地说, 集体自恋就是依赖于“他者之钦佩和承认”的集体自尊(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009, p.1085), 或者依赖于外部承认的内群体伟大性(greatness)信念(Cichocka, 2016; Golec de Zavala, 2018)。那么在这些研究者眼里, 集体自恋的内涵主要涉及两方面, 其一是夸大的内群体形象, 其二是这种夸大的形象需要获得外部承认——也就是说, 单单夸大的内群体形象不足以构成集体自恋, 集体自恋者还渴望或要求他者对内群体的夸大形象予以承认或认可。

集体自恋一开始是作为一种内群体认同(ingroup identification)被引入实证研究的, 但这种内群体认同还牵涉一种对“内群体伟大无比”这一不现实信念的情感投入(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009)。根据该领域开创者们(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009, 2019)的观点, 处于集体自恋概念核心的是一种对于内群体卓越性(exceptionality)未充分受到外部承认的不满, 而且各种理由都可以被用来声称这种卓越性或非凡性, 诸如超拔的道德观念、博大精深的文化、强大的经济或军事实力、对民主价值的捍卫, 甚至是不寻常的苦难与牺牲, 或者内群体所展现的能力、品质等。集体自恋的理由到底为何, 取决于内群体在自身区别于外群体的一些积极方面上的现行规范叙事(normative narrative)。并且, 无论理由为何, 集体自恋信念都反映着对于内群体从其他群体当中脱颖而出的渴望, 以及对于该目标实现所受到的潜在威胁的担心。

需要注意的是, 集体自恋中的“集体”可以指代个体所属的不同类别的集体或者说群体(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009)。这意味着, 人们可以对自己所属的各种社会群体感到自恋。目前, 集体自恋相关研究所涉及的社会群体至少已经有国家、种族(如Golec de Zavala et al., 2009), 政党(如Bocian et al., 2021), 宗教派别(如Marchlewska et al., 2019), 异性恋群体(如Marchlewska, Górska et al., 2021), 大学校友(如Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, & Bilewicz, 2013), 工作团队(如Cichocka et al., 2021), 体育团队(如Larkin & Fink, 2019)等。总体而言, 其中受到关注且研究最多的群体是国家(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019)2(2 简洁起见, 我们将仿照国外学者的做法, 在行文中用集体自恋来指称各种群体的集体自恋, 因为一般根据上下文就可推断出集体自恋所涉的群体为何。在可能引起歧义的地方, 我们将保留全称, 如国家集体自恋。)。

2.2 集体自恋的概念溯源

集体自恋这一概念至少可以追溯至上世纪五六十年代, 当时法兰克福学派的代表人物T. W. Adorno (1903~1969)和E. Fromm (1900~1980)就分别提出并分析过此概念, 而且他们都把集体自恋视为旨在补偿个人不足的一种对于内群体的理想化(Cichocka & Cislak, 2020; 郭永玉, 2022)。例如, 前者于1951年已经基于S. Freud的精神动力学理论表达过类似观点, 尽管当时他还未使用集体自恋一词, 仅指出自恋在群体认同中可能发挥的重要作用(Adorno, 1951); 而在稍晚的《伪文化理论》(Adorno, 1959/1993)一文中, 他已经明确提出集体自恋:“集体自恋相当于:通过使自己在事实上或在想象中成为某个更高和更具统摄性的整体的成员, 人们补偿了自己在社会上的无力感(这种无力感直抵个体的本能驱力丛), 同时也补偿了自己的内疚感(它源于个体没能按照理想自我形象成为自己所应成为的样子并做自己所应做的事情); 对于这个整体, 人们把自己所缺乏的品质都归给它, 并从中得到回报——像是感同身受式地共享着这些品质。” (pp.32-33)在他看来, 集体自恋可以被视为自我的一种防御机制, 弱小自我“如果没有寻求认同于集体的力量和光荣作为补偿, 就会遭受难以忍受的自恋损伤” (Adorno, 2005, p.111)。

相比于Adorno, Fromm更全面地分析了集体自恋, 即他笔下的“群体自恋” (group narcissism)或“社会自恋” (social narcissism)。在其著作《人心:人的善恶天性》中, Fromm (1964)专门用一个章节探讨了“个体自恋和社会自恋”, 他认为, 群体自恋与个体自恋一样可按良性与恶性形式划为两类:良性自恋(benign narcissism)会把自恋对象聚焦于需要去完成的成就上, 由于成就的实现有赖于联系并结合现实, 自恋倾向可被约束在一定限度内, 同时又能推动成员去为实现成就而努力; 恶性自恋(malignant narcissism)则把自恋对象聚焦于原本拥有的事物上, 如群体特质或过去成就等, 由于缺少来自现实的约束作用, 自恋倾向及由之产生的危险就可能增加。因而, 当群体自恋不超过一定限度时, 它不必然是消极的。进一步, Fromm还归纳了群体自恋的病理特征, 主要包括:缺乏客观和理性判断; 需要从内群体自恋形象中获得满足; 具有高度的威胁敏感性; 渴望认同于强大领袖。在Fromm (1973)看来, 个人在生活中越是缺少真实满足, 其群体自恋程度可能就越深, 因群体自恋能补偿自我的可怜状况。他还认为, 群体自恋是人类攻击行为最重要的原因之一。

3 集体自恋的现有研究积累

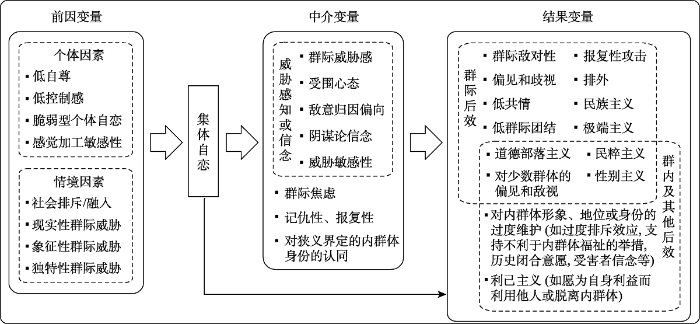

自从开创集体自恋实证研究领域的文章(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009)在顶尖期刊《人格与社会心理学杂志》发表以来, 研究者们对集体自恋展开了广泛探索。大体而言, 前期研究主要聚焦于集体自恋对一系列群际心理与行为结果的预测效应, 以确立集体自恋的独立地位; 近几年的研究则在继续验证集体自恋对众多社会现象的解释力的同时, 也开始尝试探明集体自恋的成因或前因变量, 以期将来构建出成熟的理论模型。结合该领域的较新文献(Cichocka & Cislak, 2020; Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2021; Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020), 现有研究成果大体可以由图1所概括。

图1

3.1 集体自恋的后效

3.1.1 群际威胁感知

群际威胁包括现实性群际威胁和象征性群际威胁, 而且人们对群际威胁的感知并不一定准确(Stephan et al., 2016; see also Guerra et al., 2020)。一般来说, 集体自恋者较容易高估来自外群体的威胁, 不论这种威胁是过去的、现在的、真实的还是想象出来的(Cichocka et al., 2016; Golec de Zavala et al., 2009, 2016; see also Bertin et al., 2022)。例如有研究(Golec de Zavala & Cichocka, 2012)发现, 集体自恋能预测受围心态(siege mentality), 即认为世界上其余群体对内群体有着高度的负面意图, 这可以作为夸大的群际威胁的一项指标。类似地, 集体自恋也能预测敌意归因偏向(hostile attribution bias), 这种偏向表现为把外群体感知为对内群体怀有敌意(Dyduch-Hazar, Mrozinski, & Golec de Zavala, 2019)。

另有研究(Cichocka et al., 2016)以2010年的“斯摩棱斯克空难”为背景、以波兰人为样本直接考察了集体自恋与威胁感知及阴谋论信念的关系。这场空难造成了包括波兰总统及其夫人在内的88名波兰政府代表团成员丧生。由于这场悲剧发生在俄罗斯, 当时有阴谋论声称该空难是俄罗斯在背后谋划。调查结果发现, 集体自恋既能预测个人对自身和国家所受威胁的更高感知, 又能进一步预测对上述阴谋论的相信程度。根据这些研究者的看法, 阴谋论信念也可作为夸大的群际威胁的一项指标, 表现了对外群体的高度怀疑。不过需要注意的是, 集体自恋者并非倾向于相信所有阴谋论; 如果阴谋论所声称的并不是外群体在密谋对付内群体, 而是内群体部分成员(如本国政府)在做不利于其他成员(如本国民众)的事情, 集体自恋就可能无法预测阴谋论信念(Cichocka et al., 2016)。

还有研究(Golec de Zavala et al., 2016)考察了集体自恋者对于内群体形象所受到的威胁的高度敏感性。结果发现, 即便不是确切受到外群体侮辱的情况(即那些存在争议的、他人并不这样感知的或并非对方有意的情况), 集体自恋者仍然更倾向于将其感知为内群体受到了侮辱。例如, 在其中一项以土耳其人为样本的调查中, 在阅读了当时一则关于土耳其的欧盟入盟申请被搁置的新闻后, 集体自恋水平较高者相比较低者更为感到羞辱和可耻。那么, 这种结果即体现出了集体自恋者对群际威胁的高度敏感性。

3.1.2 群际态度与行为

根据一项元分析(N = 14592), 集体自恋与对外群体的敌对性(outgroup hostility)的相关系数为0.19 (Golec de Zavala et al., 2019)。既然集体自恋者的群际威胁感知更高, 不难理解他们为何容易对外群体表现出更消极的态度和行为。例如, 集体自恋能够通过群际焦虑而预测对外群体的较低共情以及较低群际团结度(Górska et al., 2020)。又如美国人的集体自恋能预测他们对2003年伊拉克军事干预的支持度, 而且起到中介作用的是对本国受到敌对威胁的感知(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009)。并且一项以中美关系为背景的调查(Cai & Gries, 2013)发现, 无论在美国还是中国, 集体自恋都能预测对对方国民的偏见、对对方政府的负面态度以及对采取强硬政策对付对方国家的支持度。类似地, 一项以波兰人为样本的调查(Golec de Zavala & Cichocka, 2012)发现, 国家集体自恋可以预测反犹偏见——表现为与犹太人之间的社会距离更远, 对他们的负面情绪和行为意向水平更高; 而且这种关系是由威胁感知所中介。

进一步研究发现, 上述关系可能受到群际威胁情境的调节。如在一系列实验(Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, & Iskra-Golec, 2013)中, 研究者以不同群际环境(如国家之间、学校之间)为背景, 考察了内群体形象威胁对集体自恋与群际敌对反应两者关系的调节作用。结果一致发现, 在内群体受批评的条件下, 集体自恋能预测更高水平的敌对反应; 在内群体受赞扬的条件下, 集体自恋对敌对反应的预测作用不显著。这似乎表明, 集体自恋者的敌对反应一般都是报复性的, 仅指向给内群体带来威胁的外群体。实际上, 上述研究也验证了这种看法。如在阅读了一名英国留学生对美国的批评后, 美国集体自恋者只对这名留学生的同胞表现出了敌意, 而没对作为对照组的德国人表现出敌意(Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, & Iskra- Golec, 2013)。另有研究表明, 对于在历史上伤害过内群体的外群体, 集体自恋者也同样记仇、不易宽恕(Hamer et al., 2018)。还有研究发现, 集体自恋者的报复反应除了直接形式的, 还有间接形式的, 比如对外群体的不幸遭遇表现出幸灾乐祸(schadenfreude) (Golec de Zavala et al., 2016)。不过值得留意的是, 集体自恋者的负面群际反应可能不全是报复性。例如有研究(Antonetti & Maklan, 2018)发现, 集体自恋者倾向感到自己与外群体成员的相似度较低, 并对企业失责行为的外群体受害者表达出较低同情心。

众多政治心理学研究还发现, 诸如意识形态、公民投票等政治心理与行为也经常反映出集体自恋者的排外(xenophobia)倾向(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019)。例如, 集体自恋可以预测美国选民在2016年总统大选时对特朗普的支持(Federico & Golec de Zavala, 2018; Marchlewska et al., 2018), 英国民众对脱欧的支持(Golec de Zavala et al., 2017), 还有波兰、匈牙利民众对民粹主义政府及其政策的支持(Cislak et al., 2018; Forgas & Lantos, 2019; Marchlewska et al., 2018)。促成这些结果的重要因素是集体自恋者所感知到的来自外群体的威胁, 比如英国脱欧支持者倾向于认为英国受到了移民和外国人的威胁, 这种威胁感知在集体自恋与脱欧意愿之间起中介作用(Golec de Zavala et al., 2017)。另外, 集体自恋能够预测民族主义(Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2021)。在族群冲突背景下, 集体自恋还能预测对政治极端主义和恐怖主义暴力的支持, 而且这种关系在激进社会环境(如暴力被合理化的环境)中尤其突出(Jasko et al., 2020)。

3.1.3 群内态度与行为及其他后效

从上文可知, 集体自恋者在群际态度和行为方面的表现比较负面。那么在群内态度和行为方面, 集体自恋者的表现又如何呢?实际上, 内群体的部分成员也可能被集体自恋者视为对内群体形象、地位或身份构成威胁, 因而也可能被敌视。例如几项以波兰人为样本的研究发现, 不论是通过著作揭示了波兰历史污点的波兰裔美国历史学者, 还是通过电影呈现了本国不光彩历史的本国制片人及主演, 抑或是嘲笑了政府宣传标语的本国名人, 国家集体自恋者都更倾向于对这些内群体成员做出直接和间接的敌对反应, 而且起中介作用的是感知到的侮辱或冒犯(Cichocka et al., 2015; Golec de Zavala et al., 2016)。不仅如此, 最近有研究发现波兰人的国家集体自恋也能预测对同性恋者的憎恶和恐惧, 其中发挥链式中介作用的一环是把同性恋者感知为本国受到的威胁(Mole et al., 2021); 而且波兰人的国家集体自恋和宗教集体自恋各自能预测对女性的歧视(Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021)。研究者对此的解释是, 在波兰的国家集体自恋者眼中, 波兰的卓越性部分源于对传统天主教的忠诚, 纯正波兰人意味着男性、天主教和异性恋; 这样, 同性恋者和非传统女性就构成了对这种狭义界定的国家身份的威胁, 因而容易受歧视。这种现象即属于所谓的“内群体的过度排斥效应” (ingroup over- exclusion effect), 说明了部分内群体成员可能因他们未能积极反映内群体形象或身份而受到其他成员排斥(Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020)。

由这些研究可见, 集体自恋者相当在意内群体的形象、地位或身份不受威胁。那么, 这是否意味着集体自恋者相比非集体自恋者更加关切内群体的福祉呢?研究者们最近在这方面也进行了一些探索。有研究(Cislak et al., 2018)通过三项调查发现, 不论是对煤炭产业提供财政补贴(研究1), 还是批准对受保护森林的砍伐(研究2和3), 波兰的国家集体自恋皆能预测对这些有害环境的政策的支持; 其中研究2和3还发现, 起中介作用的是对本国决策独立性的支持——对此的解释是, 这项政策当时受到了科学家异议, 并被欧盟法院尝试叫停, 但集体自恋者倾向于维护本国在决策上的独立性并拥护该政策, 而不惜它可能对本国生态环境造成破坏。另有研究(Cislak et al., 2021)显示, 集体自恋者更不倾向于支持实实在在的环保政策, 但更倾向于支持在环保方面的国家表面形象工程。

最近有调查发现, 在新冠疫情面前, 集体自恋不仅较难正向预测个体与同胞的团结度, 在控制了内群体满意度后甚至能负向预测与同胞的团结度(Federico et al., 2021); 另外它能正向预测个人囤货行为(Nowak et al., 2020)。还有调查(Marchlewska, Cichocka et al., 2021)发现, 集体自恋能预测社会犬儒主义(social cynicism), 即对人性的消极看法, 由此还能预测对民主制度的较低支持。甚至有调查(Marchlewska et al., 2020)显示, 若出国能在财富上对自己更有利, 国家集体自恋水平较高者相比较低者具有更高的出国移民意愿。而且在组织环境下, 集体自恋者被发现更倾向于工具性地利用本组织成员而为自己谋利(Cichocka et al., 2021), 表现出了利己主义。那么这些研究基本上说明了集体自恋者对内群体福祉的关切水平未必更高; 对集体自恋者而言, 内群体怎样被人感知以及个人的利益似乎比内群体成员的真正福祉更重要(Cichocka & Cislak, 2020)。当然, 这并不意味着集体自恋者不在意内群体利益, 尤其是面对群际利益矛盾之时。例如集体自恋者在牵涉群际利益矛盾的道德判断中容易表现出“道德部落主义” (moral tribalism), 他们更倾向于把偏向内群体利益的行为判断为道德的(Bocian et al., 2021)。

除了前述种种后效以外, 集体自恋被发现还能预测其他一些后效, 主要还是与内群体形象或地位的维护有关。例如在面对内群体形象受到的威胁时, 集体自恋者很可能采取否认或回避等策略来保护内群体形象。具体来说, 有研究者(Imhoff, 2010)以德国人为调查对象, 考察了集体自恋与历史闭合意愿(desire for historical closure)的关系。所谓历史闭合意愿, 就是个体想要让内群体脱离过去历史影响的程度, 在这项调查中被操作化定义为德国人渴望摆脱二战时期大屠杀记忆的程度。结果发现, 集体自恋程度越高, 历史闭合意愿也越高, 这进而可以降低集体愧疚感以及对受害者进行补偿的意愿。另有一项以波兰人为样本的研究(Marchlewska et al., 2020)发现, 当面对呈现了本国不光彩历史的电影时, 集体自恋者表现出了更高水平的内群体形象防御, 如否认影片中历史情节的真实性, 并认为这些电影是在恶意抹黑波兰。还有研究(Skarżyńska & Przybyła, 2015)显示, 集体自恋者更倾向于相信本国的受害者身份(victimhood), 因为遭受苦难可能让内群体占领道德高地并增强自身价值感(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019)。

3.2 集体自恋的前因

集体自恋一般被视为一种具有相对稳定性的信念(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019), 它不但可能受到个体因素的影响, 还可能在一定程度上受到情境因素的影响。因此, 近年来已有一些研究对集体自恋的前因展开了探索, 不过这方面的成果还远不及集体自恋后效方面的成果丰富。

3.2.1 个体因素

在控制感方面, 一个包括多项调查和实验的研究(Cichocka et al., 2018)直接探讨了个人控制与集体自恋及内群体认同之间的关系, 结果表明, 缺乏个人控制确实会增加集体自恋, 但这种效应需要排除内群体认同的干扰后才浮现或更显著。具体来说, 该研究首先在一项横断调查中发现, 个人控制与集体自恋呈负相关, 并且这种相关在将内群体认同作为协变量加以控制后更显著。接着一项实验发现, 降低个人控制的操纵能提升集体自恋, 但这种现象只在内群体认同得到控制后才存在。在最后一项纵向调查中, 结果还发现, 时间点1的个人控制, 可以负向预测时间点2 (即6周后)的集体自恋, 但时间点1的集体自恋与时间点2的个人控制无关。因此, 这几项研究基本上表明了个人控制的缺乏可能是集体自恋的重要促成因素之一。另一项具有全国代表性的调查也支持了个人控制与集体自恋的这种关系(Marchlewska et al., 2020)。

在自尊方面, 尽管过去研究(如Golec de Zavala et al., 2009, 2016)未能揭示它与集体自恋的关系, 最近有研究(Golec de Zavala et al., 2020)通过更深入的横断、纵向调查和实验则一致发现, 较低的自尊确实能导致更高水平的集体自恋, 但该关系同样需要排除其他变量(即内群体满意度)的干扰后才容易观察到。值得注意的是, 该研究还比较了个人控制与自尊对集体自恋的影响, 结果发现, 当把个人控制作为协变量加以控制后, 自尊仍能负向预测集体自恋, 进而预测外群体贬损; 而把自尊作为协变量加以控制后, 个人控制则无法负向预测集体自恋, 进而也无法预测外群体贬损。这暗示, 个人控制对集体自恋的影响可能是通过自尊而产生的, 自尊相比个人控制可能是集体自恋更为近端的影响因素。另外, 有研究(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019)通过元分析发现, 集体自恋与脆弱型个体自恋的正相关水平更高且更稳健, 而与自大型个体自恋的正相关则偏小且结果存在不一致性; 还有纵向研究发现脆弱型个体自恋可以预测数周后的集体自恋(Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020)。又鉴于自尊与脆弱型个体自恋呈负相关而与自大型个体自恋呈正相关(Miller et al., 2017), 研究者(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019)推测低自尊与集体自恋可能是通过脆弱型个体自恋而联系起来的。

3.2.2 情境因素

既然集体自恋可能受到控制感与个体自尊等个体因素的影响, 那么能影响这些个体因素的情境因素很可能也能影响集体自恋。沿着这一思路, 研究者们(Golec de Zavala et al., 2020)通过实验考察了社会融入(social inclusion)和社会排斥(social exclusion)这组情境因素对集体自恋的影响, 结果发现, 社会排斥组参与者的状态自尊水平显著低于社会融入组参与者的状态自尊水平, 但两组的集体自恋差异并不显著; 但是当把内群体满意度作为协变量控制后, 两组的集体自恋水平出现了显著差异, 社会排斥组参与者呈现出了更高水平的集体自恋。也就是说, 社会排斥能通过降低个体自尊而提升集体自恋, 但这种效应需要控制了内群体满意度后才容易观察到。

另有研究(Marchlewsk et al., 2018)考察了个体所感知到的内群体劣势处境对集体自恋及民粹主义支持度的影响, 结果不但发现群体相对剥夺能正向预测集体自恋, 还发现突显内群体劣势的操纵能导致更高水平的集体自恋。例如在其中一项以英国民众为参与者的实验中, 当阅读了有关“英国因长期受到欧盟的强势影响而权力受损”的评论后, 个体报告了更高水平的集体自恋和脱欧倾向。有研究(Guerra et al., 2020)进而考察了群际威胁对集体自恋的影响, 结果发现, 在受到群际威胁时, 不论是象征性群际威胁(如内群体的价值观、自尊或信念系统受到威胁), 还是现实性群际威胁(如物质上或身体上受到威胁), 抑或是内群体区别于外群体的独特性受到威胁(distinctiveness threat), 个体的集体自恋水平都会提升。最近还有一项研究通过调查发现, 无论是对于优势地位群体, 还是劣势地位群体, 社会身份威胁都能预测个体对其所属群体的集体自恋(Bagci et al., 2021)。

3.3 集体自恋的其他相关研究

除了上述关于集体自恋后效与前因的研究, 其他受到关注比较多的是已在前文涉及的集体自恋与其他变量(如内群体认同、内群体满意度等)之间的遮掩效应(suppression effect) (如Bertin et al., 2022; Cichocka et al., 2016; Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, & Bilewicz, 2013; Marchlewska et al., 2020)。鉴于可能遮掩集体自恋效应的变量有很多, 研究者们(Cichocka, 2016; Golec de Zavala, 2011)提出了一个用于容纳这些变量的更上位概念, 即非自恋型的内群体积极性(non-narcissistic ingroup positivity)。相比于集体自恋, 非自恋型内群体积极性描述了一种更客观而非夸大的、更安全而非防御性的对于内群体的感知, 它对内群体的积极评估独立于他者对内群体的承认, 并能预测对外群体更积极的态度与行为。

在实证研究中, 由于集体自恋与非自恋型内群体积极性之间一般存在正相关, 而且两者在许多后效上有着相反的预测, 可以预见的是, 两者能在一定程度上互相遮掩对方的效应。例如有不少研究(如Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, & Bilewicz, 2013; Golec de Zavala et al., 2016)发现, 当集体自恋与非自恋型内群体积极性的正相关被控制后, 集体自恋能预测对外群体的更多贬损; 同时, 非自恋型内群体积极性则能预测更少的外群体贬损, 并能预测对外群体更积极和宽容的态度和行为——这种正效经常被集体自恋的效应所遮掩。又如, 有研究(Dyduch-Hazar, Mrozinski et al., 2019)让参与者观看了一部包含本国不光彩历史的电影预告片, 然后让参与者对影片艺术价值进行评价。结果发现, 只有当集体自恋与内群体满意度的相关被控制掉后, 集体自恋才能预测对影片艺术价值的负面评分, 而内群体满意度才能预测对影片艺术价值的正面评分。类似地, 还有研究(Golec de Zavala, 2019)通过比较简单相关与偏相关结果后发现, 集体自恋与内群体满意度的正相关能减弱集体自恋与负面情绪、自我批评的正相关, 以及集体自恋与社会联结、感恩的负相关。

4 现有研究不足及展望

4.1 集体自恋内涵与结构的厘清

如前文已经指出的, 集体自恋起初是作为一个把自恋对象从个体水平延伸至群体水平的概念而被引入实证研究的, 其定义及量表编制很大程度上借鉴了个体自恋(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; see also Lyons et al., 2010)。因此, 集体自恋在内涵和结构上皆可能面临与个体自恋相似的争议和挑战, 并需要进一步厘清和研究。首先需要厘清的是集体自恋的内涵是否一定包含脆弱性(fragility)。前文提到, 该领域的开创者们(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009)把集体自恋理解为依赖于“他者之钦佩和承认”的集体自尊, 或者说“夸大的而又不稳定的集体自尊”。实际上, 这种理解与个体自恋领域的“面具模型” (mask model; Kuchynka & Bosson, 2018)和“自我调节过程模型” (self- regulatory process model; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001)相一致, 假定了自恋者内心的脆弱性, 正是因为内心脆弱, 自恋者才需要外部肯定或承认。虽然上述脆弱性在Golec de Zavala等人(2009)的研究(N = 262)中得到验证, 即内隐联想测验发现集体自恋者确实在内隐水平上表现出较低的内群体评价, 但最近一项样本量更大(N = 481)、旨在重复Golec de Zavala等人(2009)研究的预注册研究(Fatfouta et al., 2021)却未能得到此结果, 而发现集体自恋与内隐集体自尊的相关约为0。可见, 对于集体自恋是否包含脆弱性这一问题, 当前研究还未形成定论, 并且有必要进一步探索, 因为脆弱性在集体自恋相关研究的理论解释和预测上都发挥关键作用(Golec de Zavala, 2011, 2018)。其实, 脆弱性在个体自恋领域也仍是一个研究问题(Kuchynka & Bosson, 2018), 有些研究者(如Miller et al., 2021)认为脆弱性是个体自恋的必要属性, 而另一些研究者(如Mota et al., 2020)则持有不同观点。不难发现, 也有少数学者(如Bizumic & Duckitt, 2009; Cai & Gries, 2013; Lyons et al., 2010; Putnam et al., 2018)对集体自恋或群体自恋提出过不同理解, 他们的定义都未包含脆弱性, 不过他们都未论及脆弱性这一重要理论问题。鉴于此, 本文在此提出, 集体自恋不一定包含有脆弱性, 也就是说, 既可能存在包含脆弱性的集体自恋, 也可能存在不包含脆弱性的集体自恋。而且未来研究可以参考个体自恋领域的做法(如Krizan & Herlache, 2018), 尝试适当缩小概念内涵而拓展其外延, 从而涵盖并探索更完整而丰富的集体自恋现象。更具体地说, 在个体自恋领域, 有学者(Krizan & Herlache, 2018)在充分整合了人格、社会心理、临床领域的个体自恋相关研究和理论后, 提出了一个备受关注的“自恋光谱模型” (narcissism spectrum model) (Donnellan et al., 2021), 该模型通过缩小个体自恋的内涵、将其重新定义为“享有特权的自我重要性” (entitled self-importance), 使得其外延能容纳个体自恋的多种表现型——既有包含脆弱性的自恋, 又有不包含脆弱性的自恋(如自大型自恋), 而且它们都可以按照自大性(grandiosity)、自我重要性(self-importance)、脆弱性(vulnerability)这三个基本维度所构成的坐标来描述或定位。那么借鉴这一思路, 未来研究可以考虑把集体自恋的内涵理解为“享有特权的内群体重要性”, 这样其外延就可以容纳包含脆弱性和不包含脆弱性的集体自恋。

其次, 鉴于集体自恋内涵可能较为复杂, 有必要厘清它是一个单维结构还是一个多维结构, 以及如果它是一个多维结构, 它有哪些维度。Golec de Zavala等人(2009)最初在编制集体自恋量表时, 得到了一个包含9个项目的、具有单维结构的量表。由于该领域目前仅有这一个经过反复验证、信效度良好的量表, 后续绝大多数研究都使用该量表并将其作为单维结构来考察。然而, 考虑到个体自恋牵涉多个维度(Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Miller et al., 2017), 又考虑到集体自恋可能包含、也可能不包含脆弱性, 有理由推测集体自恋可能并非一个单维结构。其实, 最近有研究提出了集体自恋的多维模型, 并编制了一个包含特权/剥削性(entitlement/exploitativeness)、支配/傲慢(dominance/arrogance)、冷漠(apathy)、钦佩(admiration)四个子维度的量表(Montoya et al., 2020)。不过该研究仅聚焦于不包含脆弱性的集体自恋, 并且只是一个初步尝试, 说明了有必要进行多维度的探索; 至于集体自恋的维度到底有哪些, 很可能需要更多研究才能得到较精准的解答, 而且不同表现型的集体自恋可能具有不同子维度, 这也需要进一步探索。本文认为, 这方面也可以从个体自恋领域获得启发, 因为过往研究对个体自恋的表现型及子维度都提出过众多划分标准(如:余震坤 等, 2019; Krizan & Herlache, 2018), 而且目前已有系统的归纳(如Rogoza et al., 2018; Sedikides, 2021)。也许特别值得注意的是, 有研究者(Crowe et al., 2019)尝试把个体自恋视为一个具有层级结构(hierarchical structure)的构念, 整合了自恋领域过去与现在的重要进展(Miller et al., 2021)——即把自恋从单维构念拓展为两维构念, 进而又拓展为三维构念。具体而言, 个体自恋的层级结构为:顶层是自恋的单因素结构, 第二层是自大型自恋与脆弱型自恋的两因素结构, 第三层是能动型外向性(agentic extraversion)、对抗性(antagonism)与自恋型神经质(narcissistic neuroticism)的三因素结构, 这三个因素与自恋光谱模型(Krizan & Herlache, 2018)的三个维度相对应, 各自牵涉一些更具体的特质, 这些特质可以直接通过五因素自恋量表(Five Factor Narcissism Inventory, FFNI)而测得, 而更上层的因素可以通过对FFNI进行因素分析(如Miller et al., 2016; see also Crowe et al., 2019)或者通过专门测量这些上层因素的量表(如Rosenthal et al., 2020)而得到。这些研究者(Miller et al., 2021)指出, 这种多层次多维度的方法具有明显优势, 例如能澄清个体自恋与外显自尊的混杂关系(Crowe et al., 2019)。本文认为, 这种思路可能也适用于分析集体自恋的结构, 因为Golec de Zavala等人(2009)对集体自恋的理解和操作化定义很大程度上借鉴了个体自恋, 并融合了自大型与脆弱型自恋的特征(Rogoza et al., 2018)。因此, 集体自恋可能至少也含有自大型与脆弱型这两个基本维度。实际上, 有一项未发表的学位论文研究(Montoya, 2020)开发了自恋型群体取向量表(Narcissistic Group Orientation Scale, NGOS), 并为上述两维结构的假设提供了支持, 不过可惜的是该研究并未将NGOS与Golec de Zavala等人(2009)的量表一起考察, 因此它们之间的关系还不明确。

再次, 假设集体自恋是一个多维构念, 那么有必要厘清Golec de Zavala等人(2009)所研究或测量的构念与最基本的两种表现型的关系, 也即它更接近于脆弱型集体自恋(vulnerable collective narcissism), 还是自大型集体自恋(grandiose collective narcissism); 因为虽然他们所界定的集体自恋包含了脆弱性, 但这未必说明脆弱性是其研究或测量的构念的首要特征。当然, 根据Golec de Zavala本人的看法, 脆弱性是其团队所研究的集体自恋的固有特征, 而且是集体自恋区别于诸如民族主义等其他相近构念的关键特征(Golec de Zavala, 2011), 他们还曾将脆弱的集体自恋与自大的民族主义作为对照展开研究(Golec de Zavala, 2018)。然而, 该团队的早期核心成员Cichocka (2016)则认为当前的集体自恋内涵和测量更偏向于自大型, 为此还提出过一种以内群体消极形象与受害感(feelings of victimization)为特征的脆弱型集体自恋的设想。实际上从最初的量表编制来看, 该领域的量表(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; Lyons et al., 2010)确实都主要参考了用于测量自大型自恋的自恋人格调查表(NPI), 不过Golec de Zavala等人(2009)的量表还增加了一些反映脆弱性的项目, 涉及对批评的敏感以及对缺乏承认的感知。可见, 学者们在当前所研究的集体自恋与两种表现型的关系上还有一定分歧, 需要进一步研究来解决, 否则就如一些学者(Rogoza et al., 2018, p.43)指出的那样, 目前很难在自恋人格的多维结构或自恋光谱模型(Krizan & Herlache, 2018)中解释清楚Golec de Zavala等人(2009)所研究的集体自恋的位置。尽管如此, 作为一种推测, 本文认为Golec de Zavala等人(2009)可能倾向于研究并测量符合面具模型的、同时包含自大性与脆弱性的集体自恋, 类似于个体自恋层级结构中处于顶层的单因素构念, 它既因为牵涉对内群体卓越形象的信念而区别于脆弱型集体自恋, 又因为牵涉脆弱性而不同于单纯的自大型集体自恋, 以致它无法被简单地归入集体自恋的某一维度。最后, 无论当前研究的集体自恋是自大型还是脆弱型, 抑或是两者的混合体, 未来研究都可以专门开发不同量表来探索其他集体自恋表现型(如Montoya, 2020), 以加深对集体自恋的认识。

4.2 集体自恋的后效及补偿性

在集体自恋的后效方面, 目前绝大多数研究都聚焦于揭示集体自恋的消极效应(Cichocka & Cislak, 2020; Golec de Zavala & Keenan, 2021; Golec de Zaval & Lantos, 2020), 极少有研究直接考察并发现集体自恋的积极效应(如Żemojtel- Piotrowska, Piotrowski, Sawicki, & Jonason, 2021)。究其原因, 本文认为大体可以举出两点:第一, 在理论上, 集体自恋在最初被引入研究(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009)时就旨在用于解释内群体对外群体的敌意或攻击性, 而且它的内涵就涉及对外群体的不满之情(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019), 所以它至今仍被视为与“对外群体的恨” (out-group hate)稳健相关的“对内群体的爱” (in-group love) (Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020), 并作为一个与“安全型内群体积极性构念”形成对照的“防御型内群体积极性构念”而被研究(Cichocka, 2016)。可以说, 现有理论(Golec de Zavala, 2011; Golec de Zavala et al., 2019; Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020)基本上都把集体自恋在群际或群内态度和行为上的后效预设为消极的, 关注焦点和研究假设也多围绕于消极后效。第二, 在研究方法上, 如前文提到的, 研究者们常常会通过遮掩效应分析等方式来控制诸如内群体认同、内群体满意度等属于非自恋型内群体积极性的变量, 从而得到集体自恋与“对外群体的恨”等消极效应的更强相关, 并且他们通常倾向于把这些消极效应看作集体自恋的典型后效(如Cichocka, 2016; Golec de Zavala, Cichocka, & Bilewicz, 2013)。也就是说, 许多研究所揭示的并非现实中的集体自恋的后效, 而是剥离了积极性之后的集体自恋或者说更极端和消极的集体自恋的后效(Cichocka et al., 2018)。本文认为, 这种做法尽管有助于揭示集体自恋的消极后效并验证Golec de Zavala (2011)最初的理论构想, 但也容易把集体自恋限定在其恶性形式上, 即超出了一定限度的集体自恋, 而正常的集体自恋也可能有其积极一面。例如根据前文Fromm (1964)的经典理论观点, 尽管集体自恋是人类攻击行为最重要的原因之一, 但它在一定限度内也可能有其良性形式, 类似个体自恋也可能有适应性的一面(余震坤 等, 2019; Miller & Campbell, 2008)。又如从现实经验(如Fukuyama, 2018)而言, 人们对“内群体获得承认”的追求也有可能推动成员间的凝聚或团结, 共同为集体成就而奋斗, 或为处于弱势地位的内群体争取更多权利。也许可以说, “为承认而斗争”未必一概都是消极的(Honneth, 1992/ 1996), 尤其是当人们为“平等的承认”而斗争时, 尽管对平等承认的渴求也可能易于滑向要求承认内群体的优越性(Fukuyama, 2018)。因此, 未来研究可以尝试把集体自恋重新构想为一个具有消极、积极两面性的概念(Fromm, 1964), 从更完整的理论视角来探究集体自恋及其后效, 特别是增加对集体自恋积极后效的考察; 同时未来研究应注意恰当使用遮掩效应分析等方法, 充分说明这类方法所得结果可能只是理论上极端形式的集体自恋的后效, 而非现实中典型的集体自恋的后效。本文认为, 这样的研究既有助于更辩证地看待集体自恋, 还有助于揭示集体自恋何时及为何会带来消极或积极后效, 并得到适用性更广的结论。

针对集体自恋的积极后效, 除了可以关注内群体及其中的其他成员是否可能从集体自恋者那里获益, 尤其值得关注的是集体自恋者自身能否从集体自恋中获益(如Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020)。无论是根据经典理论(Adorno, 1959/1993; Fromm, 1964), 还是该领域领衔学者(Cichocka, 2016; Golec de Zavala, 2018)的观点, 集体自恋皆具有补偿性, 可以满足个体的心理需求。然而, 涉及集体自恋积极补偿性的研究还是十分稀少和初步性的。就本文作者所知, 目前仅有两项横断研究涉及集体自恋与个人幸福感的关系, 其中一项研究(Golec de Zavala, 2019)发现集体自恋同时与个人生活满意度、积极情绪及消极情绪呈显著正相关, 而且当控制了内群体满意度之后, 集体自恋与生活满意度、积极情绪的相关不再显著, 而与消极情绪的相关更显著; 另一项研究(Bagci et al., 2021)也得到了相近结果。不过应注意的是, 这些横断研究无法说明变量间的因果关系, 也有可能是个人幸福程度影响了集体自恋。另外还有一项研究(Golec de Zavala et al., 2020)则通过纵向设计(子研究6)分析了集体自恋与个体自尊的关系, 发现先前时间点的集体自恋与后继时间点的个体自尊之间存在显著的负相关关系, 然而在控制了内群体满意度之后却出现了一些混杂而难以解释的结果, 也即时间点2的集体自恋能显著正向预测时间点3的个体自尊, 而时间点1和时间点3的集体自恋则无法显著预测后继时间点的个体自尊。由此可见, 当前还没有一项研究为集体自恋的积极补偿作用提供有力支持, 并且有必要进一步考察此问题, 否则很难解释集体自恋为何在世界上仍如此流行。这里, 本文认为可以借鉴系统合理化(system justification)领域的理论和研究。系统合理化是一种长期而言对个体有害而短期却可能有益的虚假意识(false consciousness) (Jost, 2019)或者说一种对焦虑、内疚、不适等痛苦具有暂时缓和功能(palliative function)的意识形态(Jost & Hunyady, 2003)。鉴于集体自恋与系统合理化对个体可能有着相似作用, 未来研究可以参考系统合理化领域用于检验暂时缓和功能的研究范式(如Harding & Sibley, 2013), 采取更多纵向或实验设计来展开深入的考察。

此外, 考虑到当前多数研究只关注了国家集体自恋(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019), 未来研究值得考察不同类别社会群体乃至不同内涵的集体自恋或者说群体自恋后效, 比较它们之间的异同, 乃至与非自恋型内群体积极性后效的异同, 从而丰富该领域的成果。举例而言, 从社会群体着手, 未来研究既可以考察属于性别、社会阶层、政治立场、文化背景等特定类别的社会群体的群体自恋后效(Golec de Zavala et al., 2009), 还可以深入比较优势地位群体与劣势地位群体的群体自恋后效(如Bagci et al., 2021; Górska et al., 2022), 或者比较不同类别的社会群体的群体自恋后效, 例如有研究(Golec de Zavala & Bierwiaczonek, 2021)比较了性别、国家、宗教这三类集体自恋在预测性别主义上的异同。另外从不同内涵的集体自恋出发, 未来研究不仅可以考察自大型集体自恋与脆弱型集体自恋在后效上的异同(如Montoya, 2020), 还可以考察能动型集体自恋与共生型集体自恋在后效上的异同(如Nowak et al., 2020; Żemojtel- Piotrowska, Piotrowski, Sedikides et al., 2021)。

4.3 集体自恋的成因及干预

针对集体自恋的成因或影响因素, 正如前文所呈现的那样, 当前只有少数研究(如Cichocka et al., 2018; Golec de Zavala et al., 2020; Guerra et al., 2020)开展了探索, 揭示出集体自恋可能源于自尊或个人控制的受挫, 并且群际威胁可以强化集体自恋。显然, 目前这方面研究是远远不够的, 未来不仅有必要进行重复性研究以增加这些结论的可靠性, 还有必要展开更全面和深入的探索。例如, Cichocka (2016)曾提出内群体积极性的动机模型, 认为集体自恋可能源于满足个体的多种需求——既包括旨在规避威胁和不安全的存在性需求(existential needs), 也包括旨在降低不确定性和模糊性的认知性需求(epistemic needs)以及旨在协调好社会关系的关系性需求(relational needs)。同时Cichocka (2016)还指出, 未来研究需要充分把社会认同论(social identity theory)及自我归类论(self-categorization theory)所强调的认知和情绪因素跟上述动机模型内的因素相整合, 从而更好地解释集体自恋的形成机制。这里, 本文认为可以同时借鉴系统合理化以及族群中心主义(ethnocentrism)3(3 族群中心主义(ethnocentrism), 有时也被译为“民族中心主义”、“种族中心主义”或“我群中心主义”, 它被定义为一种强烈的本族重要感和本族中心感(Bizumic & Duckitt, 2009)。)的相关理论和研究(如Bizumic & Duckitt, 2009, 2012; Jost, 2019), 因为系统合理化在某种意义上也是一种对内群体(即个体所属的社会系统)的理想化, 而且该领域目前已经在整合动机与认知的解释路径(杨沈龙 等, 2018; Jost, 2019); 而族群中心主义则可被视为更广义的集体自恋的一个重要成分——类似于自我中心是自恋的一个重要成分(Krizan & Herlache, 2018)——而且其理论充分吸收了社会认同论、自我归类论等观点(Bizumic & Duckitt, 2012)。更具体地说, 根据族群中心主义的理论, 人们在群体中时就可能自然地赋予内群体更多重要性, 而且这种偏向可能进一步被社会环境中的群体信念、规范和意识形态或者群际威胁所强化(Bizumic & Duckitt, 2012)。例如Golec de Zavala (2018)推测, 那种旨在强调社会分歧并理想化特定群体的政治修辞(political rhetoric)可能会增加群体成员的集体自恋。还有研究(Zaromb et al., 2018)发现, 不仅人们基本上都倾向于高估本国在世界历史上的贡献或重要性, 而且不同国家民众的这种集体自恋水平存在差异, 背后机制可能涉及我方偏见(myside bias)、启发式加工、文化环境因素等等。当然, 这些因素都还只是研究者们的理论猜想, 有待进一步研究来检验。

由于集体自恋往往与消极结果相关, 很值得探索的是如何通过干预来减弱非适应性的集体自恋及其消极影响(Golec de Zavala & Lantos, 2020)。目前这方面研究还非常少, 主要也只是研究者们(如Golec de Zavala, 2018; Golec de Zavala et al., 2019; Hase et al., 2021)的理论猜想。不过他们提到两项还未发表的研究得到了可喜结果:一方面, 不仅感恩(gratitude)这种特质能弱化集体自恋与偏见的相关, 而且10分钟的正念感恩冥想可以减弱集体自恋者的敌对倾向; 另一方面, 通过实验诱发“感动” (kama muta)4(4 Kama muta, 源自梵文, 字面意思是“被爱所感动”, 它被构想为一种独特的积极情绪, 当共融性的分享关系(communal sharing relationship)突然得到强化时, 人们体验到它(Fiske et al., 2019)。)这种具有自我超越性的情绪体验, 也能有效减弱集体自恋与群际敌对的相关(Golec de Zavala et al., 2019)。因此, 未来研究可以进一步考察这些及其他类似情感或状态, 比如慈悲(如Stellar et al., 2015)、敬畏(如Dale et al., 2020)、谦卑(如Lavelock et al., 2014)等的干预作用; 同时, 还可以从集体自恋的成因着手, 探索更根本而长效的干预方案。例如, Golec de Zavala (2018)指出自我肯定(self-affirmation)训练可能是一种可行方案, 因有研究(Thomaes et al., 2009)表明, 作为一种巩固自尊的干预方法, 自我肯定训练能降低青少年个体自恋与人际攻击的联系。

4.4 集体自恋的跨文化研究

尽管该领域学者很早就提出跨文化研究的重要性, 如Golec de Zavala等人(2009)曾提议未来研究需要考察可能影响集体自恋发展的社会文化因素, 但目前这方面研究大多都基于本土样本(如Bertin & Delouvée, 2021; Wang et al., 2021; Yustisia et al., 2020)或不同地区样本(如Cai & Gries, 2013; Guerra et al., 2020)来验证集体自恋现象的跨文化或跨地区一致性, 只有少量研究考察了集体自恋现象的跨文化差异性。例如, Golec de Zavala (2018)通过一项元分析发现, 集体自恋与自大型个体自恋的关系受到文化背景影响, 也即两者相关只出现在美国和英国样本中, 而未出现在波兰、俄罗斯或中国样本中。Golec de Zavala推测个体主义与集体主义文化可能是其中的影响因素。又如, 一项基于6185名大学生样本的跨文化调查(Zaromb et al., 2018)表明, 与共享着个体主义价值观的国家或地区相比, 那些共享着与集体主义和高权力距离相关的价值观的国家或地区表现出更强的集体自恋。另有研究(van Prooijen & Song, 2021)发现, 垂直集体主义(vertical collectivism)和权力距离能解释更高水平的集体自恋和阴谋论信念。此外还有研究(Yustisia et al., 2020)表明, 个体水平上的松-紧文化(cultural tightness and looseness)与集体自恋具有一定程度的相关性。可见, 社会文化因素确实可能影响集体自恋的发展, 并且未来研究有必要就此展开进一步探索。

值得一提的是, 最近有研究者(Żemojtel- Piotrowska, Piotrowski, Sedikides et al., 2021)根据个体自恋的“能动-共生模型” (agency-communion model)指出Golec de Zavala等人(2009)的集体自恋量表所测量的主要是能动型集体自恋, 故专门编制了共生型集体自恋量表(Communal Collective Narcissism Inventory, CCNI)。这里的能动与共生, 前者涉及自我保护/扩张、与他人分离、寻求掌控和独立存在等, 后者涉及开放交往、与他人联结、寻求合作和融入整体等(Bakan, 1966, p.15; 也见:潘哲 等, 2017)。根据这些研究者(Żemojtel-Piotrowska, Piotrowski, Sedikides et al., 2021)的看法, 能动型与共生型集体自恋均属自大型集体自恋, 即两者核心都是自大、特权和权力, 只不过后者把内群体在共生方面的卓越性作为内群体独特地位及特权的理由。那么, 鉴于集体主义文化背景下的个体在共生方面的自我增强动机可能更突显(Gebauer et al., 2012), 未来国内研究者可以尝试修订或改编相关量表, 并考察我国民众在这些不同类型集体自恋上的不同表现及影响。尽管现有研究发现国人的集体主义价值观在整体上有所衰落, 而个体主义价值观日益盛行(蔡华俭 等, 2020), 本文相信, 正是当前这种多元文化共存的环境, 更适合检验和比较丰富多样的集体自恋现象。

参考文献

半个多世纪来中国人的心理与行为变化--心理学视野下的研究

Freudian theory and the pattern of fascist propaganda

In G. Róheim (Ed.), Psychoanalysis and the social sciences (pp. 118-137). New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Identity bias in negative word of mouth following irresponsible corporate behavior: A research model and moderating effects

DOI:10.1007/s10551-016-3095-9 URL [本文引用: 1]

Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism

DOI:10.1037/a0034431 URL [本文引用: 1]

Social identity threat across group status: Links to psychological well-being and intergroup bias through collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction

Sensory-processing sensitivity, dispositional mindfulness and negative psychological symptoms

DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.006 URL [本文引用: 1]

Affected more than infected: The relationship between national narcissism and Zika conspiracy beliefs is mediated by exclusive victimhood about the Zika outbreak

Investigating the identification-prejudice link through the lens of national narcissism: The role of defensive group beliefs

Narcissism and ethnocentrism: A review

What is and is not ethnocentrism? A conceptual analysis and political implications

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00907.x URL [本文引用: 3]

Moral tribalism: Moral judgments of actions supporting ingroup interests depend on collective narcissism

National narcissism: Internal dimensions and international correlates

DOI:10.1002/pchj.26 URL [本文引用: 4]

The new science of narcissism: Understanding one of the greatest psychological challenges of our time - and what you can do about it

Understanding defensive and secure in-group positivity: The role of collective narcissism

DOI:10.1080/10463283.2016.1252530 URL [本文引用: 14]

Nationalism as collective narcissism

DOI:10.1016/j.cobeha.2019.12.013 URL [本文引用: 8]

Can ingroup love harm the ingroup? Collective narcissism and objectification of ingroup members

Personal control decreases narcissistic but increases non- narcissistic in-group positivity

Grandiose delusions:Collective narcissism, secure in-group identification and belief in conspiracies

In M. Bilewicz, A. Cichocka, & W. Soral (Eds.), The psychology of conspiracy (pp. 42-69). New York, NY: Routledge.

“They will not control us”: In-group positivity and belief in intergroup conspiracies

Words, not deeds: National narcissism, national identification and support for greenwashing versus genuine proenvironmental campaigns

Cutting the forest down to save your face: Narcissistic national identification predicts support for anti-conservation policies

DOI:10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.08.009 URL [本文引用: 2]

A model of the ingroup as a social resource

Drawing on theories of social comparison, realistic group conflict, and social identity, we present an integrative model designed to describe the psychological utility of social groups. We review diverse motivations that group membership may satisfy (e.g., the need for acceptance or ideological consensus) and attempt to link these particular needs to a global concern for self-worth. We then examine several factors hypothesized to influence an ingroup's utility in the eyes of its members. Attempting to unite our understanding of (a) why groups are needed and (b) what kinds of groups are useful in meeting those needs, a proposed model of the ingroup as a social resource (MISR) suggests that the dimensions of perceived value, entitativity, and identification interact to determine the overall psychological utility of an ingroup. We discuss empirical and theoretical support for this model, as well as its implications for intra- and intergroup attitudes.

Exploring the structure of narcissism: Toward an integrated solution

DOI:10.1111/jopy.12464 URL [本文引用: 3]

Awe and stereotypes: Examining awe as an intervention against stereotypical media portrayals of African Americans

DOI:10.1080/10510974.2020.1754264 URL [本文引用: 1]

Narcissism in contemporary personality psychology

In O. John, & R. W. Robins (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (4th ed., pp.625-641). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Collective narcissism and in-group satisfaction predict opposite attitudes towards refugees via attribution of hostility

Collective narcissism and in-group satisfaction predict different reactions to the past transgressions of the in-group

Collective narcissism and explicit and implicit collective self-esteem revisited: A preregistered replication and extension

Collective narcissism and the 2016 US presidential vote

DOI:10.1093/poq/nfx048 URL [本文引用: 1]

Collective narcissism, in-group satisfaction, and solidarity in the face of COVID-19

DOI:10.1177/1948550620963655 URL [本文引用: 1]

The sudden devotion emotion: Kama muta and the cultural practices whose function is to evoke it

DOI:10.1177/1754073917723167

[本文引用: 1]

When communal sharing relationships (CSRs) suddenly intensify, people experience an emotion that English speakers may label, depending on context, "moved," "touched," "heart-warming," "nostalgia," "patriotism," or "rapture" (although sometimes people use each of these terms for other emotions). We call the emotion kama muta (Sanskrit, "moved by love"). Kama muta evokes adaptive motives to devote and commit to the CSRs that are fundamental to social life. It occurs in diverse contexts and appears to be pervasive across cultures and throughout history, while people experience it with reference to its cultural and contextual meanings. Cultures have evolved diverse practices, institutions, roles, narratives, arts, and artifacts whose core function is to evoke kama muta. Kama muta mediates much of human sociality.

Understanding populism:Collective narcissism and the collapse of democracy in Hungary

In J. P. Forgas, K. Fiedler, & W. D. Crano (Eds.), Applications of social psychology (pp. 267- 291). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

The power of we: Evidence for group-based control

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.014 URL [本文引用: 1]

Communal narcissism

DOI:10.1037/a0029629

PMID:22889074

[本文引用: 2]

An agency-communion model of narcissism distinguishes between agentic narcissists (individuals satisfying self-motives of grandiosity, esteem, entitlement, and power in agentic domains) and communal narcissists (individuals satisfying the same self-motives in communal domains). Five studies supported the model. In Study 1, participants listed their grandiose self-thoughts. Two distinct types emerged: agentic ("I am the most intelligent person") and communal ("I am the most helpful person"). In Study 2, we relied on the listed communal grandiose self-thoughts to construct the Communal Narcissism Inventory. It was psychometrically sound, stable over time, and largely independent of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory-the standard measure of agentic narcissism. In Studies 3 and 4, agentic and communal narcissists shared the same self-motives, while crucially differing in their means for need satisfaction: Agentic narcissists capitalized on agentic means, communal narcissists on communal means. Study 5 revisited the puzzle of low self-other agreement regarding communal traits and behaviors. Attesting to the broader significance of our model, this low self-other agreement was partly due to communal narcissists: They saw themselves as high, but were seen by others as low, in communion.(c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved.

Collective narcissism and intergroup hostility: The dark side of “in-group love.”

DOI:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00351.x URL [本文引用: 6]

Collective narcissism:Antecedents and consequences of exaggeration of the in-group image

In A. Hermann, A. Brunell, & J. Foster (Eds.), The handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 79-88). Springer.

Collective narcissism and in-group satisfaction are associated with different emotional profiles and psychological wellbeing

Male, national, and religious collective narcissism predict sexism

DOI:10.1007/s11199-020-01193-3 URL [本文引用: 2]

Collective narcissism and anti-semitism in Poland

The paradox of in-group love: Differentiating collective narcissism advances understanding of the relationship between in-group and out-group attitudes

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00779.x URL [本文引用: 4]

Collective narcissism and its social consequences

DOI:10.1037/a0016904 URL [本文引用: 28]

Collective narcissism moderates the effect of in-group image threat on intergroup hostility

DOI:10.1037/a0032215 URL [本文引用: 1]

Collective narcissism: Political consequences of investing self-worth in the ingroup's image

Low self-esteem predicts out-group derogation via collective narcissism, but this relationship is obscured by in-group satisfaction

DOI:10.1037/pspp0000260 URL [本文引用: 4]

The relationship between the Brexit vote and individual predictors of prejudice: Collective narcissism, right wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation

Collective narcissism as a framework for understanding populism

DOI:10.1002/jts5.69 URL [本文引用: 4]

Collective narcissism and its social consequences: The bad and the ugly

Collective narcissism predicts hypersensitivity to in-group insult and direct and indirect retaliatory intergroup hostility

DOI:10.1002/per.2067 URL [本文引用: 6]

Too great to act in solidarity: The negative relationship between collective narcissism and solidarity- based collective action

DOI:10.1002/ejsp.2638 URL [本文引用: 1]

Refugees unwelcome: Narcissistic and secure national commitment differentially predict collective action against immigrants and refugees

DOI:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.11.009 URL [本文引用: 1]

An intergroup approach to collective narcissism: Intergroup threats and hostility in four European Union countries

Between universalistic and defensive forms of group attachment. The indirect effects of national identification on intergroup forgiveness

DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2018.03.052 URL [本文引用: 1]

The palliative function of system justification: Concurrent benefits versus longer- term costs to wellbeing

DOI:10.1007/s11205-012-0101-1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Distress and retaliatory aggression in response to witnessing intergroup exclusion are greater on higher levels of collective narcissism

Social context moderates the effects of quest for significance on violent extremism

DOI:10.1037/pspi0000198 URL [本文引用: 1]

A quarter century of system justification theory: Questions, answers, criticisms, and societal applications

DOI:10.1111/bjso.12297 URL [本文引用: 3]

The psychology of system justification and the palliative function of ideology

DOI:10.1080/10463280240000046 URL [本文引用: 1]

The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality

DOI:10.1177/1088868316685018 URL [本文引用: 8]

The psychodynamic mask model of narcissism:Where is it now?

In A. D. Herman, A. B. Brunel, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), Handbook of trait narcissism. Key advances, research methods, and controversies (pp. 89-95). Springer.

Toward a better understanding of fan aggression and dysfunction: The moderating role of collective narcissism

DOI:10.1123/jsm.2018-0012

[本文引用: 1]

Team identification is among the most widely studied concepts in sport fan behavior; however, with few exceptions, scholars have focused on the healthy and stable attachments fans form with their favorite team(s). In this study, we argue that this is not always the case. Drawing on literature from social psychology on a construct referred to as collective narcissism, we illustrate how sport fans' identification with their favorite team(s) may take a collectively narcissistic form that results in markedly different outcomes compared with the generally positive team identification that has been so vigorously studied in the literature. Specifically, we explore the moderating role of collective narcissism on the relationship between team identification and both dysfunctional fandom and aggression. In doing so, we illustrate the importance of measuring collective narcissism alongside team identification in future studies to provide a more complete understanding of fan dysfunction.

The quiet virtue speaks: An intervention to promote humility

DOI:10.1177/009164711404200111 URL [本文引用: 1]

Ingroup identification and group-level narcissism as predictors of U.S. citizens' attitudes and behavior toward Arab immigrants

DOI:10.1177/0146167210380604 URL [本文引用: 3]

Who respects the will of the people? Support for democracy is linked to high secure national identity but low national narcissism

Superficial in-group love? Collective narcissism predicts in-group image defense, outgroup prejudice and lower in-group loyalty

DOI:10.1111/bjso.12367 URL [本文引用: 4]

In search of an imaginary enemy: Catholic collective narcissism and the endorsement of gender conspiracy beliefs

DOI:10.1080/00224545.2019.1586637 URL [本文引用: 1]

Populism as identity politics: Perceived in-group disadvantage, collective narcissism, and support for populism

DOI:10.1177/1948550617732393 URL [本文引用: 2]

Threatened masculinity: Gender-related collective narcissism predicts prejudice toward gay and lesbian people among heterosexual men in Poland

Narcissism today: What we know and what we need to learn

DOI:10.1177/09637214211044109 URL [本文引用: 4]

Comparing clinical and social-personality conceptualizations of narcissism

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00492.x URL [本文引用: 1]

Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: A nomological network analysis

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x URL [本文引用: 1]

Controversies in narcissism

DOI:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045244 URL [本文引用: 2]

Thinking structurally about narcissism: An examination of the Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory and its components

DOI:10.1521/pedi_2015_29_177 URL [本文引用: 1]

Homophobia and national collective narcissism in populist Poland

DOI:10.1017/S0003975621000072 URL [本文引用: 1]

A multidimensional model of collective narcissism

DOI:10.1002/jts5.71 URL

Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model

DOI:10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Unmasking narcissus: A competitive test of existing hypotheses on (agentic, antagonistic, neurotic, and communal) narcissism and (explicit and implicit) self-esteem across 18 samples

DOI:10.1080/15298868.2019.1620012 URL [本文引用: 1]

Adaptive and maladaptive behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of Dark Triad traits, collective narcissism, and health beliefs

Collective narcissism: Americans exaggerate the role of their home state in appraising U.S. history

DOI:10.1177/0956797618772504

PMID:29911934

[本文引用: 1]

Collective narcissism-a phenomenon in which individuals show excessively high regard for their own group-is ubiquitous in studies of small groups. We examined how Americans from the 50 U.S. states ( N = 2,898) remembered U.S. history by asking them, "In terms of percentage, what do you think was your home state's contribution to the history of the United States?" The mean state estimates ranged from 9% (Iowa) to 41% (Virginia), with the total contribution for all states equaling 907%, indicating strong collective narcissism. In comparison, ratings provided by nonresidents for states were much lower (but still high). Surprisingly, asking people questions about U.S. history before they made their judgment did not lower estimates. We argue that this ethnocentric bias is due to ego protection, selective memory retrieval processes involving the availability heuristic, and poor statistical reasoning. This study shows that biases that influence individual remembering also influence collective remembering.

Measurement of narcissism: From classical applications to modern approaches

The Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale: A measure to distinguish narcissistic grandiosity from high self-esteem

DOI:10.1177/1073191119858410

PMID:31267782

[本文引用: 1]

Measures of self-esteem frequently conflate two independent constructs: high self-esteem (a normative positive sense of self) and narcissistic grandiosity (a nonnormative sense of superiority). Confusion stems from the inability of self-report self-esteem scales to adequately distinguish between high self-esteem and narcissistic grandiosity. The Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale (NGS) was developed to clarify this distinction by providing a measure of narcissistic grandiosity. In this research, we refined the NGS and demonstrated that NGS scores exhibit good convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity relative to scores on theoretically relevant measures. NGS scores, when used as simultaneous predictors with scores on a self-esteem measure, related more strongly to phenomena linked to narcissistic grandiosity (e.g., competitiveness, overestimating one's attractiveness, lack of shame), whereas self-esteem scores related more strongly to phenomena crucial to individuals' well-being (e.g., higher levels of optimism and satisfaction with life, and lower levels of depression, worthlessness, and hostility). The NGS provides researchers with a measure to help clarify the distinctions between narcissistic grandiosity and high self-esteem, as well as other facets of narcissism, both in theory and as predictors of important real-life characteristics.

In search of narcissus

DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2020.10.010 URL [本文引用: 3]

Przekonanie o narodowej martyrologii. Efekt kolektywnego narcyzmu, indywidualnej samooceny czy sytuacji grupy? [Belief in national victimhood. An effect of collective narcissism, individual self-esteem or in-group situation?]

Affective and physiological responses to the suffering of others: Compassion and vagal activity

DOI:10.1037/pspi0000010 URL [本文引用: 1]

Intergroup threat theory

In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (2nd ed., pp. 255-278). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Reducing narcissistic aggression by buttressing self-esteem: An experimental field study

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02478.x

PMID:19906123

[本文引用: 1]

Narcissistic individuals are prone to become aggressive when their egos are threatened. We report a randomized field experiment that tested whether a social-psychological intervention designed to lessen the impact of ego threat reduces narcissistic aggression. A sample of 405 young adolescents (mean age = 13.9 years) were randomly assigned to complete either a short self-affirmation writing assignment (which allowed them to reflect on their personally important values) or a control writing assignment. We expected that the self-affirmation would temporarily attenuate the ego-protective motivations that normally drive narcissists' aggression. As expected, the self-affirmation writing assignment reduced narcissistic aggression for a period of a school week, that is, for a period up to 400 times the duration of the intervention itself. These results provide the first empirical demonstration that buttressing self-esteem (as opposed to boosting self-esteem) can be effective at reducing aggression in at-risk youth.

The cultural dimension of intergroup conspiracy theories

DOI:10.1111/bjop.12471 URL [本文引用: 2]

COVID-19-related conspiracy theories in China: The role of secure versus defensive in-group positivity and responsibility attributions

The role of religious fundamentalism and tightness-looseness in promoting collective narcissism and extreme group behavior

DOI:10.1037/rel0000269 URL [本文引用: 2]

We made history: Citizens of 35 countries overestimate their Nation's role in world history

DOI:10.1037/h0101827 URL [本文引用: 3]

We will rescue Italy, but we dislike the European Union: Collective narcissism and the COVID-19 threat

Communal collective narcissism

DOI:10.1111/jopy.12636 URL [本文引用: 3]