1 Introduction

In daily life, people need to make decisions. These decision-making behaviors can occur not only in a specific time node, but also in different time nodes; the latter is intertemporal choice, which refers to the process in which individual make choices through psychological trade-offs between costs and benefits that occur at different time nodes (Frederick et al., 2002). Adam Smith once pointed out that intertemporal choice not only affected an individual health, wealth, and well-being, but also determined the degree of economic prosperity of a country; whether it was an individual choice of his or her health, education, marriage, and other major life, or the government’s decision-making on major national economy and livelihood issues, such as social economy, politics, culture, environment, and so on, had a strong intertemporal nature. The pursuit of short-term value or long-term value was obviously related to the growth, development, and even fate of individual and countries. The core content of intertemporal choice is delay discounting; that is, when individual choose the psychological trade-off between costs and benefits that occur in different time nodes, they always tend to give less weight to the costs and benefits of future time nodes (Green & Myerson, 2004). At present, researchers have carried out a series of studies on delay discounting in the fields of climate and environment, economic policy, retirement savings, investment, health, and education (Chen et al., 2005; Frederick et al., 2002; Laibson, 2001; Li et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2014), which helps people to make more rational judgments and decisions.

The ancient Greek philosopher Pythagoras pointed out that “anger begins with folly, and ends in repentance”, indicating that early thinkers recognized the impact of anger on human decision-making behavior. The study on the influence of anger on decision-making in contemporary psychology is mainly based on two perspectives; one is the influence of anger induced by the characteristics of decision-making events on decision-making behavior, and the other is not directly related to the decision-making event. This is also the research perspective of this study. Existing researchers have conducted a lot of studies on how anger affects human decision-making behavior, involving risk decision-making (Druckman & McDermott, 2008; Lench et al., 2011; Lerner & Keltner, 2000), moral decision-making (Small & Lerner, 2008), theory of mind (perspective taking) (Todd et al., 2015; Wiltermuth & Tiedens, 2011), gift giving (de Hooge, 2017), and helping behavior (Yang et al., 2017). As an important research direction in the field of decision-making, few studies have investigated the effect of anger on delay discounting. Therefore, the present study attempts to investigate the impact of incidental anger on delay discounting and its underlying mechanism.

1.1 Negative emotions and delay discounting

Previous studies on emotion influence delay discounting were mainly based on the theory of emotional dimension, focusing on emotion valence (positive / negative) dimension, to investigate the effect of emotion on delay discounting, but the conclusions were not consistent (Liu & Suo, 2018). Some studies have found that negative emotions can increase the discounting rate of long-term value in intertemporal choice tasks. For example, Wang and Liu (2009) found that the delay discounting rate in the negative emotion-induced group was significantly higher than in the non-emotion-induced control group, indicating that negative emotion reduced the participants’ estimation of long-term value, and showed a short-sighted tendency to value. Recently, the results of Guan et al. (2015) also reached the same conclusion that, compared with positive and neutral emotion conditions, individuals were more likely to choose the immediate reward with less value and gave up the delayed reward with higher value under the negative emotion condition. However, some studies have found that negative emotion can reduce the discounting rate of long-term value. For example, Li and Xie (2012) found that under the condition of high conflict decision-making, individual had a stronger tendency to delay value selection in negative emotional states than in positive and neutral emotional states. In addition, Luo et al. (2014) obtained similar results. What these conclusions had in common was that they all used the techniques of inducing general negative emotional states, without considering the specific forms of these negative emotions (such as anger and fear). Therefore, the difference between different conclusions may be that these studies induced different forms of negative emotion, while different forms of negative emotion may have different effects on delay discounting.

A few studies have examined the influence of different forms of negative emotions on delay discounting. Lerner et al. (2013) used emotional video materials to induce sadness and disgust. The results found that compared with the neutral emotional state, the participants in the sad state were more inclined to choose immediate rewards with less value, while there was no difference between the neutral emotional and disgust state. Researchers also used emotional video materials (She et al., 2016) and autobiographical memory task (She et al., 2017) to induce fear. The results found that fear significantly reduced the patience of individual to wait, which was manifested as a higher delay discounting rate. Zhao et al. (2017) used the trait-state anger questionnaire to investigate the influence of trait and state anger on intertemporal choice. The results showed that with low traits of anger, individual preferred the smaller immediate reward when they were in the state of low anger than when they were in a temporary state of high anger; when they were in the temporary state of high anger, compared to low-trait angry individual, high-trait angry individual preferred smaller immediate rewards. Recently, Fang et al. (2019) used pictures of emotional faces to induce disgust and fear. The results found that, compared with neutral faces, the appearance of disgusting faces made individual tend to choose smaller immediate rewards. The above research uses different negative emotion inducing materials to investigate the influence of different forms of negative emotion on delay discounting.

1.2 Anger, Appraisal-Tendency Framework and delay discounting

Anger merits such attention in decision-making for several reasons: first, anger is one of the most frequently experienced emotions in daily life. Previous studies have mostly explored the causes of anger (Fischhoff et al., 2005), ignoring the effect of anger on subsequent decision-making; second, anger has an unusually strong ability to capture attention (Solomon, 1990; Tavris, 1989), and people often use it as a decision-making clue (Clark et al., 1996; Knutson, 1996; Tiedens, 2001); third, anger has a powerful influence. Once occurring, it not only affects current decisions, but also affects judgments in situations that are not related to anger (Lerner et al., 2003; Lerner & Tiedens, 2006). Delay discounting is a common decision-making phenomenon in daily life. Existing studies only exploratively examine the influence of trait and state anger on delay discounting (Zhao et al., 2017), but there is a lack of in-depth exploration of its mechanism.

The Appraisal-Tendency Framework (ATF) suggested that emotions were related to specific appraisal tendencies. These appraisal tendencies reflected the core meaning of the events that elicited each emotion, which determined the influence of special emotion on individual decision-making (Lerner & Keltner, 2001; Smith & Ellsworth, 1985; Winterich et al., 2010). The Appraisal-Tendency Framework mainly drew on the theory of Smith and Ellsworth (1985), which distinguished six cognitive appraisal dimensions of emotion: pleasantness (the degree to which the event triggers pleasure or unpleasure), certainty (the predictability and intelligibility of the event), control (the degree to which the event can be controlled by the individual / situation), attentional activity (the degree to which the event attracts / prevents personal attention), anticipated effort (the degree to which personal effort is required / not required), and other’s responsibility (relative to the self, the degree to which others are responsible for the event)1 (1Smith and Ellsworth (1985) used a within-subjects design, requiring the subjects to recall 15 different emotional experiences, and then appraise the appraisal dimensions based on the emotional appraisal theory. For example, certainty refers to the degree of understanding, certainty, and future predictability of events that occur in the current environment when the individual experiences a specific emotion; control refers to whether the individual, when experiencing a specific emotion, believes that the events in the current environment are controlled by self, others, and the environment. These appraisal dimensions can be measured through questionnaires. The results of the study found that happiness is related to high pleasure, low responsibility, high certainty, high attentional activity, low anticipated effort, and high control; anger is related to low pleasure, high others’ responsibility, and high certainty, high attentional activity, high anticipated effort, and high control; fear is related to low pleasure, high others’ responsibility, low certainty, high attentional activity, high anticipated effort, and low control. Discriminant analysis further found that the corresponding cognitive appraisal model based on the six cognitive appraisal dimensions derived from the subjects’ responses can correctly predict 15 emotions with a 40% probability. This shows that there is a close relationship between the appraisal dimension of the event and the emotional state.). Different appraisal dimensions had different effects on a specific emotion. Among them, the appraisal dimension that played a leading role in emotion was called core appraisal theme; it can stimulate individual to form an implicit cognitive appraisal tendency to future events, so the influence of emotion on decision-making was realized through appraisal tendency. Only when the core appraisal themes matched the characteristics of the decision task to be carried out (matching principle), emotions can have an impact on subsequent decisions (Han et al., 2007). Previous researchers have investigated the influence of anger on decision-making behaviors based on the Appraisal-Tendency Framework. Research has found that anger can make individuals less helpful behaviors (Yang et al., 2017), more likely to consider others’ views as attractive, more willing to appraise others' views (Wiltermuth & Tiedens, 2011), show more severe judgments (Small & Lerner, 2008), and reduce gift giving (de Hooge, 2017).

Extending to the field of intertemporal choice, no one has investigated the influence of anger on delay discounting based on the Appraisal-Tendency Framework. Smith and Ellsworth (1985) found that anger was related to low pleasure, high others’ responsibility, high certainty, high attentional activity, high anticipated effort, and high control. It can be seen that anger, as a basic emotion, was related to high certainty and high control. At the same time, certainty and control were related to the cognitive factors in intertemporal choice (the unknown risk of long-term options and low control). For example, studies have found that in intertemporal choice, the longer waiting time for rewards means the greater risk of not getting it, and delayed rewards is considered risky and unsafe (Benzion et al., 1989; Luhmann et al., 2008; She et al., 2010); studies have also shown that control plays an important role in intertemporal choice; compared with the individuals with high control, the individuals with low control are more inclined to choose immediate rewards in intertemporal choice (Berns et al., 2007; Casey et al., 2011; Figner et al., 2010; Hare et al., 2009; Suo et al., 2018). Therefore, this study speculates that the appraisal dimensions of certainty and control can explain the influence of anger on delay discounting.

1.3 Overview of Experiments

Based on the perspective of the emotional dimension, anger should be similar to other negative emotions and have the same effect on delay discounting; however, Appraisal-Tendency Framework believed that the influence of emotions on decision-making will be limited by the matching principle, and only when the core appraisal dimension matches the salient attributes of the decision-making task to be carried out, emotion can have an impact on decision-making. Among the six appraisal dimensions, certainty and control may affect the delay discounting (Benzion et al., 1989; Berns et al., 2007; Casey et al., 2011; Figner et al., 2010; Hare et al., 2009; Luhmann et al., 2008; She et al., 2010; Suo et al., 2018). Therefore, based on the Appraisal-Tendency Framework, different forms of negative emotions should have different effects on delay discounting through certainty-control. Based on the research of Smith and Ellsworth (1985), this study selected two negative emotions, anger (high certainty-control) and fear (low certainty- control), and one positive emotion, pleasure (high certainty- control), for the following study. Experiment 1 used the autobiographical memory task to induce anger and fear, and then measured the participants’ responses in the intertemporal choice task. Experiment 1 hypothesized that compared to neutral emotional states, anger prompts individuals to choose delayed rewards with greater value, while fear prompts individuals to choose immediate rewards with less value . Experiment 2 used the experimental-causal-chain design to investigate whether the certainty-control dimension is the underlying mechanism of the effect of anger on delay discounting. Firstly, we explored, compared with neutral emotion, whether anger can improve the individual certainty-control and fear can reduce the certainty-control (Experiment 2a), and then examined, compared with low certainty-control, whether high certainty- control can reduce the delay discounting rate (Experiment 2b). Experiment 3 independently manipulated the certainty-control and valence of emotion, and used a measurement-of-mediation design to examine whether anger affects the delay discounting through certainty-control on the basis of excluding valence.

2 Experiment 1: The effect of anger on delay discounting

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

Based on the one-way between-subjects design of Experiment 1 and the calculation by G*Power 3.1.9.4, when the significance level a = 0.05 and the effect size is moderate (f = 0.25), the total sample size of 80% statistical power level was at least 159. 184 college students were recruited through advertisements, and were randomly divided into anger group, fear group, and control group. In addition, because this study focused on the effect of specific emotions on delay discounting, if participants chose “not at all” on the target emotion dimension in the emotional manipulation check (see materials and procedures for details), they were considered to be induced failures and this data should be excluded. After excluding the invalid data, leaving a final sample of 173 (89 females). The participants were aged from 18 to 25 (M = 21.86, SD = 2.82), including 55 in anger group, 59 in fear group, and 59 in control group. All participants had no history of nervous system or mental illness, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, voluntarily participated in the experiment, and signed an informed consent form. At the end of the experiment, the participants were given corresponding rewards.

2.1.2 Experimental design

One-way between-subjects design was used in this experiment, the independent variable was the emotion type (anger / fear / neutral emotion), and the dependent variable was the delay discounting rate k in the intertemporal choice task.

2.1.3 Materials and procedures

First, all participants completed the emotion induction task. Use the autobiographical memory task of Lerner et al. (Lerner & Keltner 2001; Small & Lerner, 2008) as an emotional induction method. Participants in the experimental group (anger and fear group) were asked to complete two tasks: task 1 “Please recall and list three things that make you feel very angry/scared, such as being betrayed by a friend (anger group) / watching a horror movie (fear group)”, task 2 “Choose one of the things that made you most angry / scared from the above experience and write down about it in details. Let others understand why you feel anger / fear, while others can also feel anger / fear by reading the experience”. The control group was also asked to complete two tasks: task 1 “Please list three things you normally do at night, such as washing face”, task 2 “Describe in as much detail as possible how you typically spend evenings. Describe the events in chronological order so that others can use your description to reconstruct how you spent your evening”. Prior research has shown that this type of autobiographical memory task was a valid means of inducing specific incidental emotions (Bodenhausen et al., 1994; Gino et al., 2012; Lerner & Keltner, 2001; Tiedens & Linton, 2001; Whitson et al., 2015).

Secondly, the participants completed the intertemporal choice task adapted from Kirby and Maraković (1996) Monetary Choice Questionnaire (MCQ). The original scale included 27 items, which were divided into three groups: large reward (L) (75 yuan ~ 85 Yuan), medium reward (M) (50 yuan ~ 60 Yuan), and small reward (S) (25 yuan ~ 35 Yuan). Each group had 9 items. In particular, although the amount of delayed reward varied in different groups, they all corresponded to 9 identical delay discounting rates (k); there was one item in S, M and L groups, and the delay discounting rate (k) were the same. For the convenience of measurement, on the basis of the calculation logic of the delay discounting rate (k) in the original scale, only two groups of large reward (L) and small reward (S) were selected, with a total of 18 questions.

Finally, the emotional manipulation check was performed to ensure the success of emotional induction. Referring to previous studies, we developed our own questionnaire (Ding et al., 2014; Todd et al., 2015), and participants were asked to choose the number that best expressed their feelings at the time after the two emotional words (anger, fear) on a 7-point scale from 1(not at all) to 7(very strong). The larger the number, the stronger the emotion.

At the end of the experiment, the participants filled in the basic information and got the corresponding reward.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Manipulation check

The results of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that the main effect of emotion type on the scale of anger was significant, F (2, 170) = 167.21, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.66. After multiple comparisons, the anger group reported significantly higher anger ratings (M = 5.29, SD = 1.21) than the fear group (M = 2.53, SD = 1.33) and the control group (M = 1.46, SD = 0.86). The main effect of emotion type on the scale of fear was significant, F(2, 170) = 78.41, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.48. After multiple comparisons, the fear group reported significantly higher fear ratings (M = 4.69, SD = 1.32) than the anger group (M = 2.58, SD = 1.64) and the control group (M = 1.53, SD = 1.22), ps < 0.001. This showed that emotional manipulation check was effective.

2.2.2 Delay Discounting Rate

The delay discounting rate represented the degree at which an individual discounts the delayed result. It was usually expressed by the value of k. The higher value of k means that as the delayed time increases, the subjective value discount of the delayed reward in the mind of the individual becomes higher. That is, the individual is more likely to choose a smaller immediate reward. Based on Kirby et al. (1996), the present study calculated the delay discounting rate k. First, we used the formula k = ((LDR/SIR) - 1) / Delay (Commons et al., 1987) to calculate the undifferentiated k value between the smaller and higher rewards in each question, where LDR is the higher delayed reward and SIR is the smaller immediate reward; for example, for the question “Would you rather have $55 immediately or $75 after 61 days?”, the k value of (75/55) - 1/61 = 0.006; subsequently, the participants were arranged in an ascending order of k value according to the smaller reward (S) and the higher reward (L), and the k value in the smaller reward group (S) and the higher reward group (L) were calculated respectively; finally, the geometric mean of the two k values in the smaller reward (S) and the higher reward (L) were used as the estimate of the delay discounting rate k. Because the original k value has a skewed distribution, the natural logarithm conversion of k should be recorded as k0. The K-S normal distribution test of k0 showed that K-S Z= 1.20, p = 0.114, which showed that k0 conformed to the normal distribution, and further parameter tests can be performed on it.

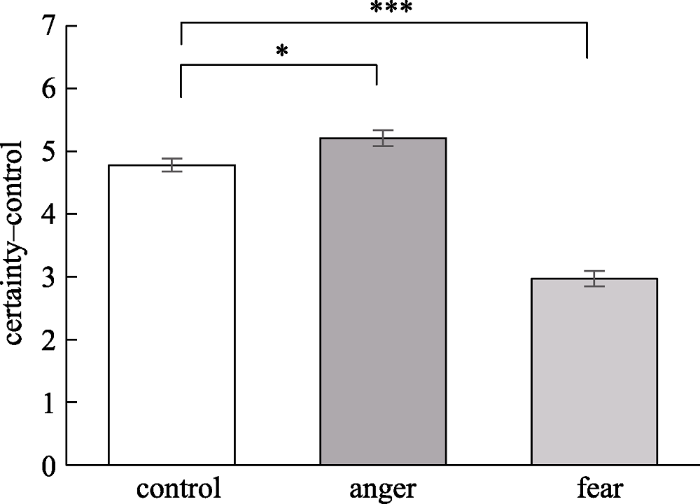

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the natural logarithm k0 of the delay discounting rate showed that the main effect of emotion type was significant, F(2, 170) = 179.30, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.68. After multiple comparisons, k0 of the fear group (M = -3.22, SD = 0.69) was significantly higher than that of the control group (M = -4.49, SD = 0.56), while k0 of the anger group (M = -5.63, SD = 0.78) was significantly lower than that of the control group (M = -4.49, SD = 0.55), ps < 0.001 (see Figure 1). This suggested that the anger participants were more likely to delay getting the higher reward than the fear and the control groups.

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The logarithm k0 of the delay discounting rate under different emotion conditions

Note. The smaller the mean, the more likely it was to delay gratification; error bars depicted standard errors; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. The same as below.

2.3 Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 supported the hypothesis that anger reduced the delay discounting. Participants in the anger group were more likely to choose a higher delayed reward than the fear and the control groups. In the last two experiments, we will explore the underlying mechanisms.

According to Appraisal-Tendency Framework, anger was associated with high certainty and control, while fear is associated with low certainty and control (Smith & Ellsworth, 1985). Therefore, in Experiment 2, we used an experimental-causal- chain (Spencer et al., 2005) to examine the role of certainty and control appraisal tendencies in the effect of anger on delay discounting. In Experiment 2a, we tested whether anger could enhance the certainty and control, and in Experiment 2b, whether the certainty and control could enhance the delay gratification.

3 Experiment 2a: The effect of anger on the certainty-control

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Participants

Based on the one-way between-subjects design of Experiment 2a the calculation by G*Power 3.1.9.4, when the significance level a = 0.05 and the effect size is moderate (f = 0.25), the total sample size of 80% statistical power level was at least 159. 184 college students were recruited through advertisement. They were randomly divided into anger group, fear group, and control group. After excluding the participants who failed to complete all tasks, leaving a final sample of 165 (96 females). The participants were aged from 18 and 26 (M = 22.12, SD = 2.59), including 55 in anger group, 55 in fear group, and 55 in control group. All participants had no history of nervous system or mental illness, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, voluntarily participated in the experiment, and signed an informed consent form. At the end of the experiment, the participants were given corresponding rewards.

3.1.2 Experimental design

One-way between-subjects design was used in this experiment, the independent variable was the emotion type (anger / fear / neutral emotion), and the dependent variable was certainty-control.

3.1.3 Materials and procedures

First, all participants completed the same autobiographical memory task as in Experiment 1.

Second, participants completed the appraisal for a certainty- control. In reference to Lerner and Keltner (2001), participants were asked to indicate how certain (1 = completely uncertain, 7 = completely certain) and controllable (1 = completely uncontrollable, 7 = completely controllable) they were about the situation described (Lerner & Keltner, 2001; Smith & Ellsworth, 1985).

Finally, participants completed the same manipulation check in Experiment 1.

At the end of the experiment, the participants filled in the basic information and got the corresponding reward.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Manipulation check

The results of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that the main effect of emotion type on the scale of anger was significant, F(2, 162) = 50.73, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.39. After multiple comparisons, the anger group reported significantly higher anger ratings (M = 5.04, SD = 1.67) than the fear group (M = 3.18, SD = 1.53) and the control group (M = 2.07, SD = 1.48). The main effect of emotion type on the scale of fear was significant, F(2, 162) = 51.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.39. After multiple comparisons, the fear group reported significantly higher fear ratings (M = 5.02, SD = 1.38) than the anger group (M = 3.65, SD = 1.66) and the control group (M = 2.09, SD = 1.48), ps < 0.001. This showed that emotional manipulation check was effective.

3.2.2 Certainty-control appraisal

The results showed that there was a significant positive correlation between the certainty and control (r = 0.56, p < 0.001). Therefore, an average of the two was used as an indicator for appraising the certainty-control (Lerner & Keltner, 2001).

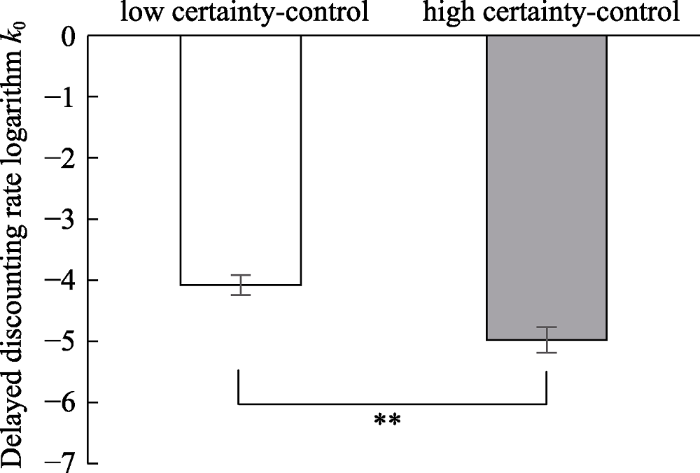

The main effect of emotion type was significant in the analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the certainty-control, F (2, 162) = 102.99, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.56. The results showed that the certainty-control (M = 5.21, SD = 0.93) of the anger group was significantly higher than that of the control group (M = 4.78, SD = 0.74), while the fear group (M = 2.97, SD = 0.92) was significantly lower than the control group (M = 4.78, SD = 0.74), ps < 0.05 (see Figure 2). This suggested that participants in the anger group experienced greater certainty and control over their own experiences.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Certainty-control under different emotional conditions.

4 Experiment 2b: The effect of certainty-control on delay discounting

4.1 Methods

4.1.1 Participants

Based on the one-way between-subjects design of Experiment 2b the calculation by G*Power 3.1.9.4, when the significance level a = 0.05 and the effect size is moderate (f = 0.25), the total sample size of 80% statistical power level was at least 128. 142 college students were recruited through advertisements, and were randomly divided into the high and low certainty-control group. After excluding the participants who failed to be emotionally induced (based on the same criteria as Experiment 1), we obtained a final sample of 132 (94 females). The participants were aged from 18 and 25 (M = 21.99, SD = 2.90), including 68 in the high certainty-control group and 64 in the low certainty-control group. All participants had no history of nervous system or mental illness, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, voluntarily participated in the experiment, and signed an informed consent form. At the end of the experiment, the participants were given corresponding rewards.

4.1.2 Experimental design

One-way between-subjects design was used in this experiment, the independent variable was the certainty-control (high /low), and the dependent variable was the delay discounting rate k in the intertemporal choice task.

4.1.3 Materials and procedures

First, all participants completed the certainty-control induction task. The autobiographical memory task of Lerner and Keltner (2001) was used as an induction method for the certainty-control. Participants were asked to complete two tasks: task 1“Please recall and list three things you feel [not] certain and [not] control as many as you can, such as brushing your teeth every day (high certainty-control) / there will be an earthquake tomorrow (low certainty-control), because we want to know under what circumstances you feel [not] certain and [not] control about what has happened and what will happen next”; task 2 “Choose one thing from the above that you feel most [not] certain and [not] control, and describe it in detail in words. Let others understand why you feel [not] certain and [not] control, and that others can also feel [not] certain and [not] control by reading about the experience.”

Secondly, the participants completed the intertemporal choice task, which was the same as Experiment 1.

Finally, participants completed the same certainty-control task as in Experiment 2a.

At the end of the experiment, the participants filled in the basic information and got the corresponding reward.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Certainty-Control manipulation check

The results showed that there was a significant positive correlation between the certainty and control (r = 0.73, p < 0.001). Therefore, an average of the two was used as an indicator for appraising certainty-control (Lerner & Keltner, 2001).

The independent-sample t test showed that the score of the high certainty-control group (M = 5.53, SD = 1.03) was significantly higher than that of the low certainty-control group (M = 2.98, SD = 1.00), t(130) = 14.40, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.78. This indicated that certainty-control manipulation was effective.

4.2.2 Delay Discounting Rate

Based on Kirby et al. (1996), the present study calculated the delay discounting rate k. Because the original k value has a skewed distribution, the natural logarithm conversion of k should be recorded as k0. The K-S normal distribution test of k0 showed that K-S Z= 1.30, p = 0.068, which showed that k0 conformed to the normal distribution, and further parameter tests can be performed on it.

The independent-sample t test on the natural logarithm k0 of delay discounting rate found that the delay discounting rate k0 of the high certainty-control group (M = -4.98, SD = 1.72) was significantly lower than that of the low certainty-control group (M = -4.08, SD = 1.28), t (130) = -3.37, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.59 (see Figure 3). This suggested that the high certainty-control group were more likely to choose to delay getting a higher amount of money than the low certainty-control group.

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The logarithm k0 of the delay discounting rate under high/low certainty-control.

4.3 Discussion

The results of Experiments 2a and 2b showed that the delay gratification effect of anger can be explained by the appraisal dimensions of certainty-control. Anger was accompanied by strong certainty-control feelings (Experiment 2a), and when the individuals choose between immediate gratification and delay gratification, certainty-control increased their tendency to delay gratification (Experiment 2b).

If certainty and control enhanced the tendency of delay of gratification in intertemporal decision-making tasks, the positive emotions related to certainty and control should have the same effect. To test this hypothesis, we added a positive emotion condition with high certainty and control -- the pleasure group in Experiment 3. We predicted that, compared with low certainty-control (fear) emotions, high certainty-control (anger and pleasure) emotions were independent of emotional valence and the individuals tended to choose larger delayed rewards in intertemporal decision-making. To further explore the role of certainty and control, we used the Baron & Kenny (1986) model to predict the mediating role of certainty-control in the intertemporal decision-making.

5 Experiment 3: The effect of anger on delay discounting: the mediating role of certainty-control

5.1 Method

5.1.1 Participants

Based on the one-way between-subjects design of Experiment 3 and the calculation by G*Power 3.1.9.4, when the significance level a = 0.05 and the effect size is moderate (f = 0.25), the total sample size of 80% statistical power level was at least 180. 201 college students were recruited through advertisements. They were randomly divided into anger group, fear group, pleasure group, and control group. After excluding the participants who failed to be emotionally induced (based on the same criteria as Experiment 1), we obtained a final sample of 193 (159 females). The participants were aged from 18 and 26 (M = 22.59, SD = 2.34), including 47 in anger group, 49 in fear group, 46 in pleasure group, and 51 in control group. All participants had no history of nervous system or mental illness, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision, voluntarily participated in the experiment, and signed an informed consent form. At the end of the experiment, the participants were given corresponding rewards.

5.1.2 Experimental design

One-way between-subjects design was used in this experiment, the independent variable was the emotion type (anger / fear / pleasure / neutral emotion), the mediating variable was certainty-control, and the dependent variable was the delay discounting rate k in the intertemporal choice task.

5.1.3 Materials and procedures

First, all participants completed the same autobiographical memory task as in Experiment 1. The pleasure condition was added. The pleasure group was asked to complete two tasks: task 1 “Recall and list as many as possible three things that made you feel very happy, such as eating your favorite food and traveling on a long trip.” and task 2 “Please choose one thing from the experience that pleases you the most and describe it in details. Let others understand why you feel happy, and at the same time others can feel happy by reading this experience.”

Second, participants completed the certainty-control task in Experiment 2a.

Then, the participants completed the intertemporal choice task, which was the same as Experiment 1.

Finally, the emotional manipulation check was performed. First, participants were asked to choose the number that best expressed their feelings based on three emotional words (anger, fear, pleasure), ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very strong); then, they were asked to rate how happy they felt, ranging from 1 (not happy at all) to 7 (very happy).

At the end of the experiment, the participants filled in the basic information and got the corresponding reward.

5.2 Results

5.2.1 Manipulation check

The results of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed that the main effect of emotion type on the scale of anger was significant, F (3,189) = 105.55, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.63. After multiple comparisons, the anger group reported significantly higher anger ratings (M = 5.02, SD = 1.22) than the fear group (M = 2.81, SD = 1.36), the pleasure group (M = 1.39, SD = 0.58), and the control group (M = 1.78, SD = 1.01), ps < 0.001. The main effect of emotion type on the scale of fear was significant, F (3,189) = 138.98, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.69. After multiple comparisons, the fear group reported significantly higher fear ratings (M = 5.06, SD = 1.09) than the anger group (M = 2.36, SD = 1.33), the pleasure group (M = 1.43, SD = 0.69), and the control group (M = 1.55, SD = 0.78), ps < 0.001. The main effect of emotion type on the scale of pleasure was significant F (3,189) = 148.35, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.70. After multiple comparisons, the pleasure group reported significantly higher pleasure ratings (M = 5.67, SD = 1.12) than the anger group (M = 1.77, SD = 0.94), the fear group (M = 1.78, SD = 0.85), and the control group (M = 4.06, SD = 1.32), ps < 0.001. This showed that emotional manipulation check was effective.

5.2.2 Certainty-control appraisal

The results showed that there was a significant positive correlation between certainty and control (r = 0.68, p < 0.001). Therefore, an average of the two was used as an indicator for appraising certainty-control (Lerner & Keltner, 2001).The main effect of emotion type was significant F (3,189) = 50.47, p < 0.001, ηp2= 0.45. The multiple comparisons results showed that the anger group (M = 5.11, SD = 1.04) and the pleasure group (M = 4.96, SD = 0.87) reported significantly higher certainty-control (ps < 0.01) than the control group (M = 4.47, SD = 0.90). However, the fear group (M = 3.10, SD = 0.77) reported significantly lower certainty-control (ps < 0.01) than the control group. There was no significant difference between the anger group and the pleasure group (p = 0.422), which suggested that emotional valence did not affect the appraisal of certainty-control.

5.2.3 Delay discount rate

Based on Kirby et al. (1996), the present study calculated the delay discounting rate k. Because the original k value has a skewed distribution, the natural logarithm conversion of k should be recorded as k0. The K-S normal distribution test of k0 showed that K-S Z= 1.10, p = 0.175, which showed that k0 conformed to the normal distribution, and further parameter tests can be performed on it.

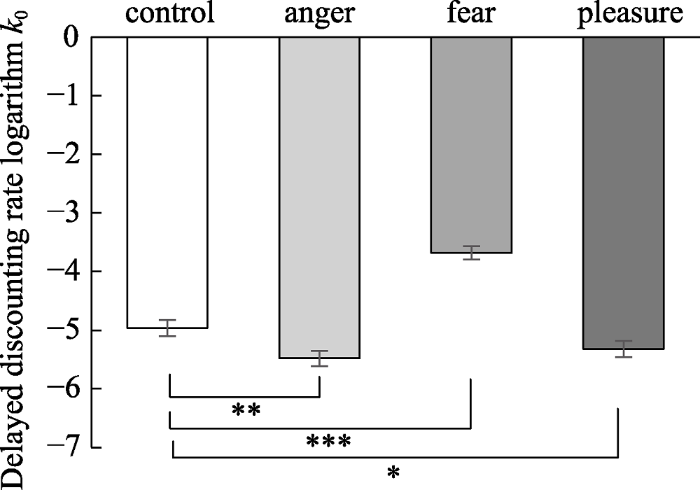

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the natural logarithm k0 of the delay discounting rate showed that the main effect of emotion type was significant, F (3,189) = 39.87, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.39. After multiple comparisons, k0 of the anger group(M = -5.48, SD = 0.89) and the pleasure group (M = -5.32, SD = 0.94) was significantly lower than that of the control group (M = -4.96, SD = 0.99), ps < 0.05, while k0 of the fear group(M = -3.68, SD = 0.78) was significantly higher than that of the control group (M = -4.96, SD = 0.99), p < 0.001 (see Figure 4). This suggested that the emotional valence did not affect the individual delay discounting.

Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The logarithm k0 of the delay discounting rate under different emotion conditions.

5.2.4 The mediating effect of certainty-control on specific emotion and delay discounting

In order to further clarify the psychological mechanism of delay discounting influenced by special emotions, Mplus 7.11 was used to examine the mediating effect of certainty-control on delay discounting by using a deviation-corrected Bootstrapping test (5000 samples). In the model of mediating effect analysis, different emotion types (anger, fear, pleasure, and neutral emotion) were coded as dummy variables, and the mediating variables certainty-control and dependent variable delay discounting rate were continuous variables. The results of the analysis of the mediating effect were as follows:

As shown in Table 1, when the control group was used as a reference, the mediating effect of the anger group through certainty-control on the delay discounting was -0.184, and the 95% confidence interval was [-0.295, -0.074], excluding “0” indicating that the mediating effect was significant; the direct effect of anger on delay discounting was -0.013, and the 95% confidence interval was [-0.098, 0.073], including “0” indicating that the direct effect is no longer significant. The mediating effect of the fear group through certainty-control on the delay discounting was 0.396, and the 95% confidence interval was [0.294, 0.498], excluding “0”, which indicated that the mediating effect was significant; the direct effect of fear on delay discounting was 0.093, and the 95% confidence interval was [-0.016, 0.203], including “0” indicating that the direct effect was no longer significant; the mediating effect of the pleasure group through certainty-control on the delay discounting was -0.141, and the 95% confidence interval was [-0.242, -0.039], excluding “0”, which indicated that the mediating effect was significant; the direct effect of pleasure on delay discounting was 0.003, and the 95% confidence interval was [-0.106, 0.113], including “0” indicating that the direct effect was no longer significant. The results showed that anger made people more likely to delay gratification, and that anger made people more likely to delay gratification by increasing their certainty-control feelings.

Table 1 An analysis of the mediating effect of certainty-control on delay discounting

| Mediation path | Estimated value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| low | High | ||

| Using the control group as reference: | |||

| Anger → certainty-control → delay discounting | -0.184a | -0.295 | -0.074 |

| Anger → delay discounting | -0.013 | -0.098 | 0.073 |

| Fear → certainty-control → delay discounting | 0.396a | 0.294 | 0.498 |

| Fear → delay discounting | 0.093 | -0.016 | 0.203 |

| Pleasure → certainty-control → delay discounting | -0.141a | -0.242 | -0.039 |

| Pleasure → delay discounting | 0.003 | -0.106 | 0.113 |

Note. a indicates that the mediator effect is significant.

5.3 Discussion

The results of Experiment 3 showed that the certainty- control played a mediating role in the process of anger influencing the delay discounting, and the underlying mechanism of anger influencing the delay discounting was realized by enhancing the certainty-control. The study further showed that the experience of emotions associated with certainty and control (i.e., anger and pleasure) during intertemporal choice, regardless of valence, enhanced the individual tendency to delay gratification.

6 General discussion

In this study, the autobiographical memory task was used as an emotion-inducing task, and the influence of anger on the delay discounting and its underlying mechanism were investigated. Through three experiments, we found that when making intertemporal choice, the anger that we incidentally experience will reduce the delay discounting rate. Compared with those who experience fear and neutral emotions, those who experience anger were more likely to choose a higher delayed reward. Importantly, the last two experiments of this study provided direct evidence that the high certainty and control associated with anger may be the underlying mechanism to reduce the delay discounting effect. Specifically, anger enhanced the individual certainty and control (Experiment 2a and Experiment 3). At the same time, high certainty and control causes individuals to be more inclined to delay gratification when making intertemporal choice (Experiment 2b and Experiment 3). In addition, Experiment 3 shows that, regardless of the valence, experiencing emotions associated with certainty and control (i.e. anger and pleasure) when making intertemporal choice will enhance the tendency to delay gratification.

This study found that anger affected the delay discounting through certainty and control. Zhao et al. (2017) explored the influence of trait and state anger on delay discounting. The results showed that for individuals with low trait anger, they tended to prefer larger delayed rewards in a state of high anger than in a state of low anger. Anger was considered to have a close relation with certainty and control, and high anger prompted individuals to make more risk-seeking behaviors (Lerner & Keltner, 2001; Smith & Ellsworth, 1985). Therefore, it was consistent with the idea of this study to choose a large amount of delayed reward in intertemporal choice. In contrast, they further found that when the individuals were in a temporary state of high anger emotions, compared with low trait anger individuals, high trait anger individuals tended to prefer smaller immediate rewards. Previous studies have found that negative emotions with high arousal may change the risk tendency associated with emotional traits (Leith & Baumeister, 1996). Therefore, when temporarily in a state of high anger, the intertemporal preferences of high trait anger individuals may change compared to low trait anger individuals. In addition to this, the study found that participants who experienced fear were more likely to choose a smaller immediate reward than those experiencing neutral emotions. This was consistent with the research results of She et al. (She et al., 2016; She et al., 2017). They used emotional video materials (She et al., 2016) and autobiographical memory tasks (She et al., 2017) to induce the state of fear, and found that fear significantly reduced the individual patience to wait, which was manifested as a higher delay discounting rate. In contrast, Fang et al. (2019) used pictures of emotional face to induce disgust and fear, and found that, compared with neutral faces, viewing fear faces did not affect individual intertemporal choice preferences. This suggested that compared to the emotional video materials and autobiographical memory tasks, the fear elicited by emotional faces is relatively short in duration and low in intensity, and may have a less impact on subsequent intertemporal choice (Fang et al., 2019). Therefore, the inconsistency of the results may be related to the experimental materials, which need to be verified under the same experimental conditions in the future.

The Appraisal-Tendency Framework (Lerner & Keltner, 2001; Winterich et al., 2010) suggested that the differences between different forms of emotions can be appraised in six dimensions: pleasure, certainty, control, attentional activity, anticipated effort, and others’ responsibility. The appraisal dimension has different effects on specific emotion. The influence of emotions on decision-making will be limited by the matching principle. Only when the core appraisal themes match the salient attributes of the decision-making tasks to be carried out, emotions have an impact on subsequent decision-making. Based on the study of Smith and Ellsworth (1985), anger has core appraisal themes such as negative valence, high certainty, high control, and high others’ responsibility. In other words, when the core appraisal dimension of anger matched the salient attributes of the decision-making task to be carried out, anger can have an impact on the decision-making. Studies have found that the high certainty and control of anger made individual more optimistic about risk appraisal, and they preferred risk seeking when making risk decisions (Druckman & McDermott, 2008; Lench et al., 2011); the high other’s responsibility in anger promoted individual to show more severe moral judgment (Small & Lerner, 2008) and reduced public support for welfare policies (Small & Lerner, 2008); the high other’s responsibility and control of anger caused individual to reduce helping behaviors (Yang et al., 2017); the high other’s responsibility and negative valence in anger led to the reduction of gift-giving (de Hooge, 2017). Appraisal-Tendency Framework has improved our understanding of the influence of anger on decision-making, and the current study supported this hypothesis that the high certainty and control of anger reduced the individual delay discounting rate. This study further speculated that different forms of negative emotions had different effects on individual intertemporal choice preferences because of their differences in the appraisal dimensions of certainty and control.

In addition to using Appraisal-Tendency Framework to explain how emotions affect delay discounting, some researchers also used the Affect-as-Information Theory, the Motivational Dimensional Model of Affect, the Construal Level Theory, and the Perceived-Time-Based Model to explain this process. Specifically, the Affect-as-Information Theory believed that emotions were informative, and emotions of different valence had different emotional information, which can affect the individual information processing strategy (Clore et al., 2001; Schwarz & Clore, 1983). However, when the Affect-as-Information Theory explained the influence of emotion on information processing, it only considered the emotional valence and ignored the influence of other dimensions on the delay discounting. The Motivational Dimensional Model of Affect predicted individual behavior from the emotional motivation dimension. It believed that the direction of motivation was divided into two categories: approach and avoidance (Gable & Harmon-Jones, 2008). Anger was a feeling of approach motivation, and anger would arise when an action toward an ideal goal was blocked (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009), while fear was a feeling of avoidance motivation that predisposed people to avoid stressful objects or situations (Gable & Harmon-Jones, 2010). The Motivational Dimensional Model of Affect helped us understand the influence of emotion on delay discounting from an evolutionary perspective. The Construal Level Theory believed that any object or event in the environment can be characterized at different construction levels (Liberman et al., 2002), which can be divided into high construction level and low construction level. Under high level construction, people tended to characterize long-term events; while under low level construction, people specifically characterized recent events. Wang and Liu (2009) believed that pleasure elicited high level construction of future money characterization, making them pay more attention to the value attribute of the result rather than time distance, and thus decreasing the rate of delay discounting; on the contrary, sadness induced low level construction of future money characterization, and made them pay more attention to the time distance of the results rather than the value attributes, so the delay discounting rate increased. In addition, Zauberman et al. (2009) proposed the Perceived-Time-Based Model to explain the cognitive mechanism of intertemporal choice. They found that the discounting rate in intertemporal choice decreases as the objective delayed time increases, and the reason may be that the individual perception of future time is biased (Zauberman et al., 2009). This study found that anger affects the individual choice preference through certainty and control. The appraisal dimension of certainty and control affects the level of construction of the participants’ future monetary characterization, and then affects the value attribute/the time distance of the result or the subjective perception of the future time, which needs further research.

Because this study recognized the limitations of a single method, it used experimental-causal-chains design (Spencer et al., 2005) and a measurement-of-mediation design (Baron & Kenny, 1986). It was found that the certainty and control of anger were the underlying mechanism of the delay discounting effect in intertemporal choice. The diversity of methods in this study proved the stability of our results. This study also had some limitations, each of which provided a possible direction for future research. First, our experiment completely relied on the autobiographical memory task to induce anger. Although this task is one of the most common and effective methods to induce specific emotions, future research can use different emotion induction methods such as watching a video clip that induces anger and experiencing a live angry event to determine the generality of the results of this study. Secondly, the intertemporal choice task of this study was adapted from the money selection scale of Kirby et al. (1996), which contains only a few intertemporal decision-making items. Future research can adopt various forms of intertemporal decision-making tasks such as titration tasks and subjective reporting tasks to improve the generality of research results. At the same time, intertemporal choice may occur in different situations, such as food choices, saving lives, cell phone purchases, public transportation, environmental pollution, and other situations (Read et al., 2017). Future research can investigate whether anger can be observed in different intertemporal situations to reduce the individual delay discounting rate.

The current study provided many other directions for future research on anger and delay discounting. First, this research focused on the impact of incidental anger caused by unrelated previous experiences. Future research should explore whether the integration of anger (caused by the goal of the decision-making task) will reduce the delay discounting rate, or whether the expected anger (caused by the anticipated future anger events) will reduce the individual delay discounting rate. Second, this study found that the anger and pleasure associated with certainty and control reduced the delay discounting rate. Future research should explore whether other emotions known to trigger appraisal tendencies toward certainty and control have the same effect. Future research should also explore whether different emotions in other appraisal dimensions (e.g., motivation dimensions) affect the delay gratification in intertemporal choice. Third, this study examined the influence of anger on intertemporal choice tasks in the context of earnings. Intertemporal choice involves two types of situations: gains and losses. A large number of studies in the field of intertemporal choice have shown that the internal cognition and neural mechanisms of loss-based intertemporal choice and profit-based intertemporal choice are not equivalent, and the research results obtained in the income context cannot be generalized to the loss context (Gehring & Willoughby, 2002; Mitchell & Wilson, 2010; Xu et al., 2009). Therefore, it was necessary to study the influence of anger on intertemporal choice in two different situations of gain and loss. Fourth, all participants in this study are young people (19 to 26 years old). Future research should examine children, adolescents, and the elderly to investigate whether the influence of anger on delay discounting differs across age groups. Studies have shown that from early adolescence to old age, the experience and expression of individual anger gradually decrease, and the ability of emotion regulation gradually increases (Brown, 2016). Therefore, in the decision-making process, compared with the elderly, young people may be more susceptible to anger.

7 Conclusion

The results of this study provide the first causal evidence; that is, when trying to understand the psychological trade-offs between costs and benefits that occur at different time nodes and making choices, the certainty and control appraisal tendencies related to anger will reduce the delay discounting rate. Whether it was an individual choice of major life such as health, education, and marriage, or a decision-making on major social, economic, political, cultural, environmental, and other livelihood issues, it had a strong intertemporal nature. Based on the Appraisal-Tendency Framework, we can study the influence of emotions on these intertemporal events more precisely. This study had important theoretical significance for understanding the emotional mechanism of intertemporal choice.

Reference

The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations

Discount rates inferred from decisions: An experimental study

Intertemporal choice-toward an integrative framework

DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.011

URL

PMID:17980645

[Cited within: 2]

Intertemporal choices are decisions with consequences that play out over time. These choices range from the prosaic--how much food to eat at a meal--to life-changing decisions about education, marriage, fertility, health behaviors and savings. Intertemporal preferences also affect policy debates about long-run challenges, such as global warming. Historically, it was assumed that delayed rewards were discounted at a constant rate over time. Recent theoretical and empirical advances from economic, psychological and neuroscience perspectives, however, have revealed a more complex account of how individuals make intertemporal decisions. We review and integrate these advances. We emphasize three different, occasionally competing, mechanisms that are implemented in the brain: representation, anticipation and self-control.

Negative affect and social judgment: The differential impact of anger and sadness

The influence of stressor exposure and psychosocial resources on the age-anger relationship: A longitudinal analysis

DOI:10.1177/0898264315624900

URL

PMID:26823387

[Cited within: 1]

OBJECTIVES: This study examined the processes linking age, stressor exposure, psychosocial coping resources, and two dimensions of anger proneness (i.e., experienced anger and expressed anger). METHOD: Longitudinal change regression analysis of data from a two-wave community panel study including a sample of people aged 18 to 93 ( N = 1,473) is performed. RESULTS: Age is significantly associated with declines in both experienced anger and expressed anger over the 3-year study period. These associations are substantially mediated by the lower levels of chronic stressors and discrimination-related stressors experienced among older adults. In contrast, self-esteem amplifies the association between age and expressed anger. DISCUSSION: These findings clarify the circumstances in which age matters most for changes over time in the experience and expression of anger. They highlight how certain forms of stressor exposure and psychosocial resources are linked with anger proneness and in ways that vary by age.

Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications

DOI:10.1037/a0013965

URL

PMID:19254075

[Cited within: 1]

The authors review a range of evidence concerning the motivational underpinnings of anger as an affect, with particular reference to the relationship between anger and anxiety or fear. The evidence supports the view that anger relates to an appetitive or approach motivational system, whereas anxiety relates to an aversive or avoidance motivational system. This evidence appears to have 2 implications. One implication concerns the nature of anterior cortical asymmetry effects. The evidence suggests that such asymmetry reflects direction of motivational engagement (approach vs. withdrawal) rather than affective valence. The other implication concerns the idea that affects form a purely positive dimension and a purely negative dimension, which reflect the operation of appetitive and aversive motivational systems, respectively. The evidence reviewed does not support that view. The evidence is, however, consistent with a discrete-emotions view (which does not rely on dimensionality) and with an alternative dimensional approach.

Behavioral and neural correlates of delay of gratification 40 years later

Cultural differences in consumer impatience

Combining emotion appraisal dimensions and individual differences to understand emotion effects on gift giving

The effect of emotions associated with certainty (happiness, anger) and uncertainty (sadness) on trust

Emotion and the framing of risky choice

The differential effects of disgust and fear on intertemporal choice: An ERP study

Lateral prefrontal cortex and self-control in intertemporal choice

DOI:10.1038/nn.2516

URL

PMID:20348919

[Cited within: 2]

Disruption of function of left, but not right, lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) with low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) increased choices of immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards. rTMS did not change choices involving only delayed rewards or valuation judgments of immediate and delayed rewards, providing causal evidence for a neural lateral-prefrontal cortex-based self-control mechanism in intertemporal choice.

Evolving judgments of terror risks: Foresight, hindsight, and emotion

URL PMID:15998184 [Cited within: 1]

Time discounting and time preference: A critical review

Approach-motivated positive affect reduces breadth of attention

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02112.x

URL

PMID:18466409

[Cited within: 1]

Research has found that positive affect broadens attention. However, these studies have manipulated positive affect that is low in approach motivation. Positive affect that is high in approach motivation should reduce the breadth of attention, as organisms shut out irrelevant stimuli as they approach desired objects. Four studies examined the attentional consequences of approach-motivated positive-affect states. Results were consistent with predictions. Participants showed less global attentional focus after viewing high-approach-motivating positive stimuli than after viewing low-approach-motivating positive stimuli (Study 1) or neutral stimuli (Study 2). Study 3 found that greater trait approach motivation resulted in less global attentional focus after participants viewed approach-motivating positive stimuli. Study 4 manipulated affect and approach motivation independently. Greater approach-motivated positive affect caused lower global focus. High-approach-motivated positive affect reduces global attentional focus, whereas low-approach-motivated positive affect increases global attentional focus. Incorporating the intensity of approach motivation into models of positive affect broadens understanding of the consequences of positive affect.

The motivational dimensional model of affect: Implications for breadth of attention, memory, and cognitive categorisation

The medial frontal cortex and the rapid processing of monetary gains and losses

Anxiety, advice, and the ability to discern: Feeling anxious motivates individual to seek and use advice

URL PMID:22121890 [Cited within: 1]

A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards

URL PMID:15367080 [Cited within: 1]

Myopic decisions under negative emotions correlate with altered time perception

DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00468

URL

PMID:25941508

[Cited within: 1]

Previous studies have obtained inconsistent findings about emotional influence on inter-temporal choice (IC). In the present study, we first examined the effect of temporary emotional priming induced by affective pictures in a trial-to-trial paradigm on IC. The results showed that negative priming resulted in much higher percentages of trials during which smaller-but-sooner reward (SS%) were chosen compared with positive and neutral priming. Next, we attempted to explore the possible mechanisms underlying such emotional effects. When participants performed a time reproduction task, mean reaction times in negative priming condition were significantly shorter than those in the other two emotional contexts, which indicated that negative emotional priming led to overestimation of time. Moreover, such overestimation was negatively correlated with performance in the IC task. In contrast, temporary changes of emotional contexts did not alter performances in a Go/NoGo task (including commission errors and omission errors). In sum, our present findings suggested that myopic decisions under negative emotions were associated with altered time perception but not response inhibition.

Feelings and consumer decision-making: The appraisal-tendency framework

Self-control in decision-making involves modulation of the vmPFC valuation system

DOI:10.1126/science.1168450

URL

PMID:19407204

[Cited within: 2]

Every day, individuals make dozens of choices between an alternative with higher overall value and a more tempting but ultimately inferior option. Optimal decision-making requires self-control. We propose two hypotheses about the neurobiology of self-control: (i) Goal-directed decisions have their basis in a common value signal encoded in ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), and (ii) exercising self-control involves the modulation of this value signal by dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). We used functional magnetic resonance imaging to monitor brain activity while dieters engaged in real decisions about food consumption. Activity in vmPFC was correlated with goal values regardless of the amount of self-control. It incorporated both taste and health in self-controllers but only taste in non-self-controllers. Activity in DLPFC increased when subjects exercised self-control and correlated with activity in vmPFC.

Delay-discounting probabilistic rewards: Rates decrease as amounts increase

DOI:10.3758/BF03210748

URL

PMID:24214810

[Cited within: 5]

The independence of delay-discounting rate and monetary reward size was tested by offering subjects (N = 621) a series of choices between immediate rewards and larger, delayed rewards. In contrast to previous studies, in which hypothetical rewards have typically been employed, subjects in the present study were entered into a lottery in which they had a chance of actually receiving one of their choices. The delayed rewards were grouped into small ($30-$35), medium ($55-$65), and large amounts ($70-$85). Using a novel parameter estimation procedure, we estimated discounting rates for all three reward sizes for each subject on the basis of his/her pattern of choices. The data indicated that the discounting rate is a decreasing function of the size of the delayed reward (p < .0001), whether hyperbolic or exponential discounting functions are assumed. In addition, a reliable gender difference was found (p = .005), with males discounting at higher rates than females, on average.

Facial expressions of emotion influence interpersonal trait inferences

A cue-theory of consumption

Why do bad moods increase self-defeating behavior? Emotion, risk taking, and self-regulation

URL PMID:8979390 [Cited within: 1]

Discrete emotions predict changes in cognition, judgment, experience, behavior, and physiology: A meta-analysis of experimental emotion elicitations

DOI:10.1037/a0024244

URL

PMID:21766999

[Cited within: 2]

Our purpose in the present meta-analysis was to examine the extent to which discrete emotions elicit changes in cognition, judgment, experience, behavior, and physiology; whether these changes are correlated as would be expected if emotions organize responses across these systems; and which factors moderate the magnitude of these effects. Studies (687; 4,946 effects, 49,473 participants) were included that elicited the discrete emotions of happiness, sadness, anger, and anxiety as independent variables with adults. Consistent with discrete emotion theory, there were (a) moderate differences among discrete emotions; (b) differences among discrete negative emotions; and (c) correlated changes in behavior, experience, and physiology (cognition and judgment were mostly not correlated with other changes). Valence, valence-arousal, and approach-avoidance models of emotion were not as clearly supported. There was evidence that these factors are likely important components of emotion but that they could not fully account for the pattern of results. Most emotion elicitations were effective, although the efficacy varied with the emotions being compared. Picture presentations were overall the most effective elicitor of discrete emotions. Stronger effects of emotion elicitations were associated with happiness versus negative emotions, self-reported experience, a greater proportion of women (for elicitations of happiness and sadness), omission of a cover story, and participants alone versus in groups. Conclusions are limited by the inclusion of only some discrete emotions, exclusion of studies that did not elicit discrete emotions, few available effect sizes for some contrasts and moderators, and the methodological rigor of included studies.

Effects of fear and anger on perceived risks of terrorism: A national field experiment

DOI:10.1111/1467-9280.01433

URL

PMID:12661676

[Cited within: 1]

The aftermath of September 11th highlights the need to understand how emotion affects citizens' responses to risk. It also provides an opportunity to test current theories of such effects. On the basis of appraisal-tendency theory, we predicted opposite effects for anger and fear on risk judgments and policy preferences. In a nationally representative sample of Americans (N = 973, ages 13-88) fear increased risk estimates and plans for precautionary measures; anger did the opposite. These patterns emerged with both experimentally induced emotions and naturally occurring ones. Males had less pessimistic risk estimates than did females, emotion differences explaining 60 to 80% of the gender difference. Emotions also predicted diverging public policy preferences. Discussion focuses on theoretical, methodological, and policy implications.

Beyond valence: Toward a model of emotion specific influences on judgement and choice

Fear, anger, and risk

DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.81.1.146

URL

PMID:11474720

[Cited within: 10]

Drawing on an appraisal-tendency framework (J. S. Lerner & D. Keltner, 2000), the authors predicted and found that fear and anger have opposite effects on risk perception. Whereas fearful people expressed pessimistic risk estimates and risk-averse choices, angry people expressed optimistic risk estimates and risk-seeking choices. These opposing patterns emerged for naturally occurring and experimentally induced fear and anger. Moreover, estimates of angry people more closely resembled those of happy people than those of fearful people. Consistent with predictions, appraisal tendencies accounted for these effects: Appraisals of certainty and control moderated and (in the case of control) mediated the emotion effects. As a complement to studies that link affective valence to judgment outcomes, the present studies highlight multiple benefits of studying specific emotions.

The financial costs of sadness

DOI:10.1177/0956797612450302

URL

PMID:23150274

[Cited within: 1]

We hypothesized a phenomenon that we term myopic misery. According to our hypothesis, sadness increases impatience and creates a myopic focus on obtaining money immediately instead of later. This focus, in turn, increases intertemporal discount rates and thereby produces substantial financial costs. In three experiments, we randomly assigned participants to sad- and neutral-state conditions, and then offered intertemporal choices. Disgust served as a comparison condition in Experiments 1 and 2. Sadness significantly increased impatience: Relative to median neutral-state participants, median sad-state participants accepted 13% to 34% less money immediately to avoid waiting 3 months for payment. In Experiment 2, impatient thoughts mediated the effects. Experiment 3 revealed that sadness made people more present biased (i.e., wanting something immediately), but not globally more impatient. Disgusted participants were not more impatient than neutral participants, and that lack of difference implies that the same financial effects do not arise from all negative emotions. These results show that myopic misery is a robust and potentially harmful phenomenon.

Portrait of the angry decision maker: How appraisal tendencies shape anger's influence on cognition

How has the Wenchuan Earthquake influenced people's intertemporal choices?

The influence mechanism of incidental emotions on choice deferral

The effect of temporal distance on level of mental construal

The cognitive and neural mechanism of the delay discounting: From the trait and state perspectives

The Influence of emotion on delayed discounting: Status quo, mechanism and prospect

Neural dissociation of delay and uncertainty in intertemporal choice

URL PMID:19118180 [Cited within: 2]

The behavioral and neural effect of emotional primes on intertemporal decisions

DOI:10.1093/scan/nss132

URL

PMID:23160811

[Cited within: 1]

Research on intertemporal behavior has emphasized trait-like variance. However, recent studies have begun to explore situational factors that affect intertemporal preference. In this study, we examined the associations between emotional primes and both behavior and brain function during intertemporal decision making. Twenty-two participants completed a dual task in which they were required to make intertemporal choices while holding an expressive face in memory. From trial-to-trial, the facial expression varied between three alternatives: (i) fearful, (ii) happy and (iii) neutral. Brain activity was recorded using functional magnetic resonance imaging for 16 participants. Behavioral data indicated that fearful (relative to happy) faces were associated with greater preference for larger but later rewards. During observation of fearful faces, greater signal change was observed in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. During subsequent decision making, the fear prime was associated with greater signal increase in structures including the posterior sector of the anterior cingulate cortex. Individual differences in this activity correlated with the magnitude of the priming effect on behavior. These findings suggest that incidental emotions affect intertemporal choice. Increased farsightedness after the fear prime may be explained by an 'inhibition spillover' effect.

The subjective value of delayed and probabilistic outcomes: Outcome size matters for gains but not for losses

DOI:10.1016/j.beproc.2009.09.003

URL

PMID:19766702

[Cited within: 1]

The subjective value of a reward (gain) is related to factors such as its size, the delay to its receipt and the probability of its receipt. We examined whether the subjective value of losses was similarly affected by these factors in 128 adults. Participants chose between immediate/certain gains or losses and larger delayed/probabilistic gains or losses. Rewards of $100 were devalued as a function of their delay (

The value of nothing: Asymmetric attention to opportunity costs drives intertemporal decision-making

Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states

General probability-time tradeoff and intertemporal risk-value model

DOI:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01344.x

URL

PMID:20136745

[Cited within: 2]

This article proposes an intertemporal risk-value (IRV) model that integrates probability-time tradeoff, time-value tradeoff, and risk-value tradeoff into one unified framework. We obtain a general probability-time tradeoff, which yields a formal representation form to reflect the psychological distance of a decisionmaker in evaluating a temporal lottery. This intuition of probability-time tradeoff is supported by robust empirical findings as well as by psychological theory. Through an explicit formalization of probability-time tradeoff, an IRV model taking into account three fundamental dimensions, namely, value, probability, and time, is established. The object of evaluation in our framework is a complex lottery. We also give some insights into the structure of the IRV model using a wildcatter problem.

The effect of fear on intertemporal choice: An experiment based on recalling emotion

Does fear increase impatience in inter — temporal choice? Evidence from an experiment

Emotional policy: Personal sadness and anger shape judgments about a welfare case

Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion

URL PMID:3886875 [Cited within: 9]

Establishing a causal chain: Why experiments are often more effective than mediational analyses in examining psychological processes

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.845

URL

PMID:16393019

[Cited within: 2]

The authors propose that experiments that utilize mediational analyses as suggested by R. M. Baron and D. A. Kenny (1986) are overused and sometimes improperly held up as necessary for a good social psychological paper. The authors argue that when it is easy to manipulate and measure a proposed psychological process that a series of experiments that demonstrates the proposed causal chain is superior. They further argue that when it is easy to manipulate a proposed psychological process but difficult to measure it that designs that examine underlying process by utilizing moderation can be effective. It is only when measurement of a proposed psychological process is easy and manipulation of it is difficult that designs that rely on mediational analyses should be preferred, and even in these situations careful consideration should be given to the limiting factors of such designs.

The effect of ego depletion on different self-control-trait individual in intertemporal choices

Anger and advancement versus sadness and subjugation: The effect of negative emotion expressions on social status conferral

URL PMID:11195894 [Cited within: 1]

Judgment under emotional certainty and uncertainty: The effects of specific emotions on information processing

DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.81.6.973

URL

PMID:11761319

[Cited within: 1]

The authors argued that emotions characterized by certainty appraisals promote heuristic processing, whereas emotions characterized by uncertainty appraisals result in systematic processing. The 1st experiment demonstrated that the certainty associated with an emotion affects the certainty experienced in subsequent situations. The next 3 experiments investigated effects on processing of emotions associated with certainty and uncertainty. Compared with emotions associated with uncertainty, emotions associated with certainty resulted in greater reliance on the expertise of a source of a persuasive message in Experiment 2, more stereotyping in Experiment 3, and less attention to argument quality in Experiment 4. In contrast to previous theories linking valence and processing, these findings suggest that the certainty appraisal content of emotions is also important in determining whether people engage in systematic or heuristic processing.

Anxious and egocentric: How specific emotions influence perspective taking

The effect of mood on intertemporal choice

The emotional roots of conspiratorial perceptions, system justification, and belief in the paranormal

Incidental anger and the desire to evaluate

Now that I’m sad, it’s hard to be mad: The role of cognitive appraisals in emotional blunting

DOI:10.1177/0146167210384710

URL

PMID:20876386

[Cited within: 2]