1 引言

人们在日常生活中会经历各种压力事件或困境, 此时会向身边的亲密伴侣寻求亲近和帮助, 如果伴侣在身边并且给予积极的回应, 压力或困境的感受便会得到缓解, 获得安全感。这一生活中常见的场景便是成人依恋系统运作模式的简要描绘。短时来看, 安全感的获得能带来诸多的积极效应, 例如可以提升对自我和他人的积极评价(Baccus, Baldwin, & Packer, 2004), 有助于心理健康和亲社会行为(Carnelley & Rowe, 2007; Rowe & Carnelley, 2003)、创造性的问题解决及情绪调节等(Mikulincer et al., 2003; Mikulincer, Shaver, & Rom, 2011)。长期来看, 成功地依赖寻求亲近来获得安全感可以影响个体的身心健康和关系结果(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016)。已有依恋领域的研究主要集中于考察依恋作为认知脚本如何影响身心健康(Beyderman & Young, 2016; Wei, Liao, Ku, & Shaffer, 2011)、关系结果(Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Cusimano & Riggs, 2013)或认知加工过程(Dykas & Cassidy, 2011), 而较少有对依恋安全感获得方式的探讨。然而探究这一问题, 不仅可以明确依恋系统的工作方式, 也能为依恋安全的干预带来启发。

1.1 依恋控制系统模型与依恋安全感的获得

依恋的控制系统模型(control-systems model of attachment)由Mikulincer和Shaver (2003) 提出, 是用来概括成人依恋系统工作方式的重要理论模型。该模型在解释依恋系统激活、依恋安全感的获得以及依恋个体差异的影响中发挥了重要作用。模型指出, 依恋系统的工作可以划分为三个相对独立的成分。

第一个成分涉及到对于内外部威胁信号的监控和评估, 决定了依恋系统是否处于激活状态。当个体感知到潜在的或者真实的威胁之后, 会自动激活依恋系统, 并加强对于依恋相关认知的通达性, 促进对于伴侣的亲近寻求行为。这一部分较少受到依恋个体差异的影响(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003); 第二个成分涉及到对依恋对象可得与反应性的监控和评估。对于依恋对象是否可得和反应的回答将会直接决定个体安全感的获得。可得与反应信息主要来源于真实出现的依恋对象的情况以及环境因素所激活的安全的依恋表征(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003); 第三个成分涉及到对是否亲近寻求是处理依恋不安全感有效手段的监控和评估。依恋对象不可得或低反应将会导致依恋不安全感, 并继续伴随着威胁所导致的困境感受; 还会导致个体采取次级依恋控制策略来进行应对, 包含去激活策略(deactivation)和过度激活策略(hyperactivation)。依恋焦虑个体会更加倾向采取过度激活的策略, 他们会放大威胁的严重性、对于依恋对象是否可得和反应高度警觉。依恋回避个体更倾向于采取去激活的策略, 他们会表现出压抑消极的情绪或认知, 远离威胁的信号和情境。这一过程体现了依恋个体差异的影响(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003)。

从依恋控制系统模型可知, 并非所有安全依恋的个体在任何情境中都能获得依恋安全感, 也并非所有不安全依恋的个体在任何情境中都无法获得依恋安全感。依恋控制系统同时强调个体特质(依恋风格或依恋取向)以及特定情境的作用(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016)。在特定情境下, 个体是如何获得依恋安全感的呢?依恋控制系统强调, 通过接近内在安全的依恋表征可以通达伴侣反应性的信息, 进而获得依恋安全感。依恋理论认为这一安全依恋表征的核心是安全基地脚本(secure base script), 即关于支持寻求、支持可得和困境缓解的一系列程序性知识(Waters & Waters, 2006)。通过安全基地脚本可以通达伴侣可得与反应性的信息, 进而获得依恋安全感(Waters & Waters, 2006)。安全依恋的个体拥有更易接近、更加丰富和更为连贯的安全基地脚本, 并且更擅长使用亲近寻求的方式来处理威胁情境(Mikulincer, Shaver, Sapir-Lavid, & Avihou-Kanza, 2009)。

除对于安全基地脚本的通达外, 依恋相关的情节加工也有助于个体获得依恋安全感。不同于脚本表征的抽象概括, 情节表征是对于特定时间特定地点对依恋自传体事件的表征, 它强调特定情境下依恋系统的作用。相关的理论及研究证据间接支持了情节记忆在依恋系统中的作用。成人依恋理论较为一致地认为, 依恋的内部工作模式包含情节记忆的成分(Bowlby, 1973; Collins & Allard, 2004; Collins & Read, 1994; Dykas & Cassidy, 2011; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016)。Mikulincer和Shaver (2003)在依恋控制系统模型中就提到, 依恋系统的激活可以强化记忆网络中依恋相关情节的通达性。Alea和Bluck (2007)发现回忆与伴侣相处的自传体事件可以有效增加个体感知到的关系亲密感。关于依恋启动的研究通过让被试回忆和视觉化一段感觉安全的亲密关系, 可以提升依恋安全感(Mikulincer et al., 2005; Rowe et al., 2012)。这些研究结果表明, 依恋相关的情节表征同样也可能让个体通达伴侣反应性信息并有助于安全感的获得。

然而, 情节表征不仅包含情节记忆一种形式, 也包含情节模拟(Szpunar, Spreng, & Schacter, 2014)。那么是否依恋相关的情节模拟也可以在依恋系统中发挥重要作用, 帮助个体获得依恋安全感呢?虽然依恋理论有相关的论述, 但仍无实证研究探讨此问题。

1.2 情节模拟及其在依恋系统中的作用

以往认知心理学的研究中, 关于个体如何回忆过去或记忆的研究蓬勃发展, 取得了令人瞩目的成就。而相比较而言, 对于人类前瞻(prospection)或想象未来能力的研究则在近年来才开始得以关注(Seligman, Railton, Baumeister, & Sripada, 2013; Wilson & Gilbert, 2005)。前瞻性信息加工指的是对未来可能发生事件的表征和加工过程(Schacter, Addis, & Buckner, 2008; Seligman et al., 2013)。Szpunar等人(2014)概括了4种主要形式的前瞻性加工, 即对未来情景的模拟(simulation)、预期(prediction)、意图(intention)和计划(planning)。本研究所关注的情节模拟便是前瞻性加工中的一种。

情节模拟(episodic simulation)指的是对特定未来自传体事件心理表征的建构过程(Szpunar et al., 2014), 它在我们日常生活中随时发生(Barsics, van der Linden, & D'Argembeau, 2016; D'Argembeau, Renaud, & van Der Linden, 2011)。这一认知加工过程包含几个特点:首先, 情节模拟依赖于情节记忆系统, 过去经验的情节信息是情节模拟素材的来源; 其次, 情节模拟包含自我的参与, 对未来情景的模拟是以自传体的形式进行; 第三, 类似于回忆过去事件的重新经历感(re-experience), 情节模拟具有指向未来的预先体验感(pre-experience); 第四, 情节模拟具有高度适应性, 允许个体以多种不同的方式建构模拟未来可能发生的事件而不用采用真实的行为(Schacter, 2012)。情节模拟有助于我们的跨期决策、情绪调节、前瞻记忆以及空间导航等等(Schacter, Benoit, & Szpunar, 2017)。

依恋理论指出, 依恋的内部工作模式也包含预期等指向未来的信息加工的成分(Collins & Read, 1994; Collins & Allard, 2004)。内部工作模式存储着多种“如果…那么…”的模式, 这种模式使得个体可以在心理上进行“小规模的实验”来模拟未来的依恋相关事件(Bowlby, 1969)。也就是说, 依恋的内部工作模式允许个体进行与依恋对象交往的情节模拟(Bretherton & Munholland, 2008; Gallese, 2005)。Bowlby (1969,1980)也认为这种模拟和依恋对象交往的过程组成了依恋的内部工作模式。此外, 当个体与依恋对象交往时, 内部工作模式可以允许个体编码对依恋对象的期望, 允许个体在心理上模拟和预期多种依恋行为的可能结果, 决定个体在多种社会情境下怎样去感知和反应。依恋系统可以允许个体以具身模拟(embodied simulation)的方式理解他人的行为(Bretherton & Munholland, 2008)。从这些依恋理论的不同论述中可以看到, 依恋的内部工作模式或依恋系统的作用一定程度上依赖于情节模拟过程。

本研究认为, 依恋相关的情节模拟同样可以通达伴侣可得与反应性信息, 帮助个体获得安全感。依恋的控制系统的论述指出, 依恋系统是对于威胁和痛苦应对的一种机制。这一应对机制包含两种不同的应对成分:情绪聚焦的应对(emotion-focused coping)和问题聚焦的应对(problem-focused coping)。情绪聚焦的应对过程指的是确认和表达感受并且寻求情绪的支持。而问题聚焦的应对指的是寻求工具性的支持和问题解决以缓和困境感受(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003)。关于情节模拟的理论和研究表明, 情绪聚焦的应对和问题聚焦的应对过程都可以从情节模拟中获益(Jing, Madore, & Schacter, 2016, 2017; Taylor & Schneider, 1989)。例如, 模拟消极事件可能出现的好的结果可以增加个体对消极事件的积极再评价并提升主观幸福感(Jing et al., 2017)。

综上所述, 已有研究主要关注依恋脚本这一通达伴侣可得与反应的方式, 却忽略了情节加工在依恋系统中的作用。本研究认为, 建构依恋相关的情节模拟也可以通达伴侣可得与反应性的信息, 帮助个体获得依恋安全感。为了验证这一假设, 本研究提供给被试困境问题情境, 要求被试进行伴侣支持下的困境问题解决的情节模拟。因伴侣的可得与反应指的是伴侣的帮助、支持或积极回应, 研究中将以预期伴侣反应性来概括预期的伴侣的可得与反应的程度。研究主要考察是否依恋相关的情节模拟可以增加预期的伴侣反应性并提升状态性的依恋安全感。此外, 关于情节模拟的理论指出, 情节模拟可以促进行为及行为计划的产生, 增加个体表现出相应行为的意愿(Rivkin & Taylor, 1999)。已有研究也发现情节模拟可以增加个体对消极事件积极评价(Jing et al., 2017), 以及模拟帮助他人可以增加帮助意愿(Gaesser & Schacter, 2014)。因此本研究也探索性地考察是否依恋相关的情节模拟可以降低对于情境困境程度的评价并增加个体亲近寻求的意愿。结合以上分析, 本研究假设, 情节模拟可以增加预期的伴侣反应性和状态性的依恋安全感, 并降低困境感受的评价, 增加亲近寻求意愿。

2 方法

2.1 被试

在研究开始前, 采用G*Power 3.1进行统计检验力分析来决定所需样本大小, 表明共需至少34名有效被试以足够用来获得中等效应量的前后测与组别的交互作用(power = 0.80, α = 0.05, two-tailed, within-between interaction, effect size f = 0.25)。随后招募处于恋爱关系中且恋爱时长超过6个月的年轻人共计46名(选择恋爱时长超过6个月以确保被试处于相对稳定的恋爱关系中, 且有较多和伴侣相处的经验), 其中实验组被试23名(其中男生8名, 恋爱时长范围为6~70月, 平均的恋爱时长为29.3 ± 19.97月, 异地恋被试9名, 被试年龄范围为19~ 27岁, 平均年龄为22.57 ± 1.95岁), 控制组被试23名(其中男生10名, 恋爱时长范围为6~98月, 平均的恋爱时长为30.87 ± 31.05月, 异地恋被试6名, 被试年龄范围为19~29岁, 平均年龄为24.09 ± 2.54岁)。

2.2 实验材料

困境问题情境。通过预实验评定恋爱中常见的困境问题情境, 为情节模拟任务及控制组任务提供情境材料。选取相关研究中收集的恋爱中常见的困境事件共25个, 这些事件涵盖恋爱关系中常见的事件类型, 包含有伴侣缺失、自私、忽视、背叛、分离、冲突、欺骗、关系破裂、误解、批评和客观压力等(王岩, 2017)。

随后招募正处于恋爱关系中且恋爱时长超过6个月(平均的恋爱时长为33.36 ± 18.92月)的在校大学生11名(其中男生3名, 被试的平均年龄为23 ± 2.91岁)进行材料评定。评定内容包含:熟悉性(即“类似的场景在你生活中出现过, 听说过, 或者你对它们的了解程度”), 发生频率(即“生活中经历此情境或类似情境的频率”), 困境程度(指的是“当你处于此描述的情境中时, 你感到焦虑、伤心或者痛苦的程度”), 可控程度(指的是“描述中的情境对你来说可以控制或可以改变的程度, 即当你处于此情境时你知道怎么做让事情变得更好的难易程度”)。评定均为1~7的7点评分。

选取其中熟悉性、困境感受大于4, 即对处于恋爱关系的大学生来说感到熟悉、评定为困境的情境; 可控程度大于4, 即可控程度较高, 不可控事件表明结果是确定且不可改变的, 无法进行问题解决相关的模拟(如亲友死亡); 发生频率为2~6之间, 2以上即表明事件是有可能发生在恋爱大学生情侣间的事件, 发生频率为6以下目的是避免任务的完成完全基于通常行为反应模式来完成任务。在被试评定完后, 结合情境类型是否重复, 最后选取6个符合要求的情境作为后续研究的材料。

情节模拟任务。该任务参考先前的研究中关于情节模拟对帮助他人意图影响的研究改编而来(Gaesser & Schacter, 2014)。针对预实验所获得的困境情境内容改编成问题解决情节模拟任务。在该任务中, 首先给被试呈现问题情境的初始状态和相应的问题解决的结果状态, 要求被试针对每个情境进行依恋相关的情节模拟, 即想象怎么向伴侣寻求帮助以及怎么在伴侣的帮助之下解决问题, 如何从开始的困境状态到达目标状态的。需要被试列出具体所采取的步骤。总共有7个试次, 包含1个练习试次和6个正式的试次。

情境结果撰写任务。控制组进行情境结果撰写任务, 任务的情境同情节模拟组的情境, 要求被试根据情境尽可能多地写出该情境发生在一对情侣之间的所有可能结果, 要求写出的情境结果不一定发生在自己和恋人间, 发生在任何情侣间的可能结果都可以写。总共有7个试次, 包含1个练习试次和6个正式的试次。

预期伴侣反应性及依恋安全感评定。在第一次任务开始前及第二次实验任务完成后进行情境评定。评定内容包含4个方面:即假定自己处于当前问题情境之中, 要求被试评定:(1)感到困境的程度, (2)向恋人寻求帮助和支持的意愿, (3)在此情境下恋人会给予自己帮助、支持或回应的程度(预期伴侣反应性), (4)状态性的依恋安全(包含3个题项)。其中, 状态性的依恋安全问题来源于Gillath, Hart, Noftle和Stockdale (2009)编制的状态性依恋问卷, 该问卷包含3个维度, 即依恋安全、依恋焦虑和依恋回避。选取原问卷编制文献中每个维度下因子载荷最高的题项用于本研究的情境评定问题, 具体问题包含:“我感到被人爱”(依恋安全); “我此刻有一种无条件被爱的强烈需要”(依恋焦虑); “如果此刻有人试图接近我, 我会尽力与他/她保持距离”(依恋回避)。所有评定的题项均设置为1~9的9点评分。上述6个测量项目在6个情节模拟试次上的一致性分别为前测:0.74, 0.75, 0.68, 0.79, 0.86, 0.93; 后测:0.71, 0.64, 0.80, 0.78, 0.88, 0.94。

亲密关系经历量表。亲密关系经历量表用来测量个体的依恋取向, 即个体较为稳定的依恋特质的个体差异, 在本研究中作为控制变量。该量表最初由Brennan, Clark和Shaver (1998) 开发, 本研究中使用了由李同归和加藤和生(2006)修订的中文版本。该问卷由36个项目组成, 包含两个维度, 每个维度18个项目:依恋回避维度用来评估个体对于伴侣亲密的不舒适程度, 题项如“当恋人跟我过分亲密的时候, 我会感到内心紧张”; 依恋焦虑维度用来评估害怕被伴侣抛弃的感受, 题项如“我担心我会被抛弃”。所有项目为从1(完全不同意)到7(完全同意)的7点计分。该问卷在中国群体中有较好的信效度。在本研究中的内部一致性(Cronbach's α)为, 依恋焦虑0.81, 依恋回避0.82。

2.3 实验设计与流程

研究采用实验组控制组前后测设计。其中, 实验组进行情节模拟任务, 控制组进行结果撰写任务。前后测包含的主要指标有预期伴侣反应性和状态性依恋安全, 同时加入对问题情境困境感受的评定及寻求伴侣支持意愿的评定。该研究的自变量为:测量时间(被试内变量; 前测vs.后测), 组别(被试间变量; 实验组:情节模拟组vs.控制组:结果撰写组); 因变量为:预期伴侣反应性、状态性依恋安全、情境困境感受及寻求伴侣支持意愿; 控制变量为:依恋取向(特质性依恋的个体差异)。

实验分两次进行, 间隔时间为3天以上, 所有被试首先完成基本信息问卷、依恋个体差异问卷, 并对预实验获取的6个情境进行评定。要求被试假定自己当前分别正处于6段描述的情境中, 然后来评定感到困境的程度、向恋人寻求帮助和支持的意愿、觉得在此情境下恋人会给予自己帮助或支持的程度以及状态性的依恋安全。3天后, 所有被试被随机分配到实验组和控制组中, 实验组要求被试针对给定的情境进行情节模拟, 模拟的内容为在此情境下他们怎么向伴侣寻求帮助以及怎么样在伴侣的支持和帮助下解决问题的, 要求被试在3分钟的时间内尽可能多和详细地写出模拟出的步骤来, 每个情境模拟完后进行同第一次实验时的评定; 控制组的实验流程类似, 针对每个情境, 要求被试在3分钟的时间内尽可能多地列出这个情境发生后的所有可能的结果, 每个试次完成后也进行相同的4个方面共6个项目的评定。

3 结果

3.1 实验组控制组前测比较

为了考察实验分组的有效性, 首先比较了实验组和控制组对6个情境评定的前测成绩(表1), 研究结果显示, 在情境的困境感受、向恋人寻求帮助和支持的意愿、预期的伴侣会给予自己帮助、支持或回应的程度以及状态性的依恋安全感6个评定项目的前测成绩上, 实验组和控制组之间无显著的差异(ps > 0.05), 表明实验分组有效。

表1 实验组控制组前测成绩的差异

| 变量 | 实验组(n = 23) | 控制组(n = 23) | t | p | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 困境感受 | 6.09 ± 1.20 | 5.40 ± 1.60 | 1.65 | 0.11 | 0.50 |

| 寻求支持意愿 | 6.51 ± 1.21 | 5.93 ± 1.40 | 1.48 | 0.15 | 0.45 |

| 预期伴侣反应性 | 6.41 ± 1.03 | 6.25 ± 1.16 | 0.51 | 0.61 | 0.15 |

| 状态依恋安全 | 5.41 ± 1.33 | 5.28 ± 1.47 | 0.31 | 0.76 | 0.09 |

| 状态依恋焦虑 | 5.74 ± 1.80 | 5.14 ± 1.72 | 1.16 | 0.25 | 0.35 |

| 状态依恋回避 | 5.64 ± 1.84 | 5.20 ± 2.28 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 0.22 |

3.2 实验组控制组前后测比较

实验组控制组各评定内容的描述性统计结果如表2所示。

表2 实验组控制组前后测成绩的描述性统计

| 变量 | 实验组(n = 23) | 控制组(n = 23) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 前测 | 后测 | 前测 | 后测 | |

| 困境感受 | 6.09 ± 1.20 | 5.90 ± 1.23 | 5.40 ± 1.60 | 5.23 ± 1.53 |

| 寻求支持意愿 | 6.51 ± 1.21 | 6.93 ± 0.97 | 5.93 ± 1.40 | 6.12 ± 1.36 |

| 预期伴侣反应性 | 6.41 ± 1.03 | 7.20 ± 1.08 | 6.25 ± 1.16 | 6.32 ± 1.35 |

| 状态依恋安全 | 5.41 ± 1.33 | 6.44 ± 1.00 | 5.28 ± 1.47 | 5.12 ± 1.20 |

| 状态依恋焦虑 | 5.74 ± 1.80 | 5.63 ± 1.87 | 5.14 ± 1.72 | 5.33 ± 1.92 |

| 状态依恋回避 | 5.64 ± 1.84 | 4.65 ± 2.26 | 5.20 ± 2.28 | 5.41 ± 2.40 |

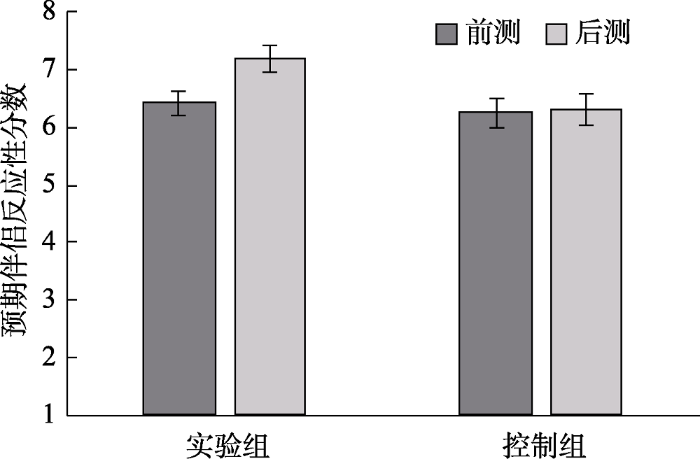

为了比较实验组与控制组是否有差异, 分别以六个测量的变量进行多个2(测量时间:前测vs.后测) × 2(组别:实验组vs.控制组)的方差分析。方差分析的结果显示, 在困境感受上, 测量时间主效应不显著, F(1,44) = 0.95, p = 0.34; 组别的主效应不显著, F(1,44) = 3.41, p = 0.07; 交互效应不显著, F(1,44) = 0.003, p = 0.96。在寻求支持的意愿上, 存在显著的测量时间的主效应, F(1,44) = 4.50, p = 0.04, 偏η2 = 0.09, 后测的寻求支持的意愿要显著大于前测的寻求支持意愿; 有显著的组别的主效应, F(1,44) = 4.20, p = 0.05, 偏η2 = 0.09, 实验组低于控制组; 无显著的交互效应, F(1,44) = 3.41, p = 0.07; 在预期的伴侣反应性上, 无显著的组别主效应, F(1,44) = 2.71, p = 0.11; 存在显著的测量时间主效应, F(1,44) = 12.03, p < 0.001, 偏η2 = 0.22, 及显著的测量时间和组别的交互效应, F(1,44) = 8.33, p = 0.006, 偏η2 = 0.16 (如图1)。简单效应分析的结果表明, 实验组后测的预期伴侣反应性要显著高于前测, t(22) = 4.57, p < 0.001, d = 0.77, 而在控制组条件下, 前后测的伴侣反应性之间无显著的差异; 此外, 在前测的评定上实验组控制组没有差异, 而后测评定上实验组预期的伴侣反应性比控制组高, t(44) = 2.46, p = 0.02, d = 0.85。

图1

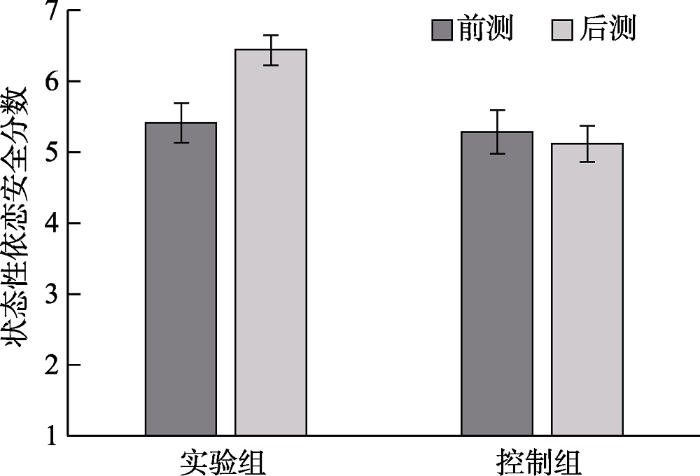

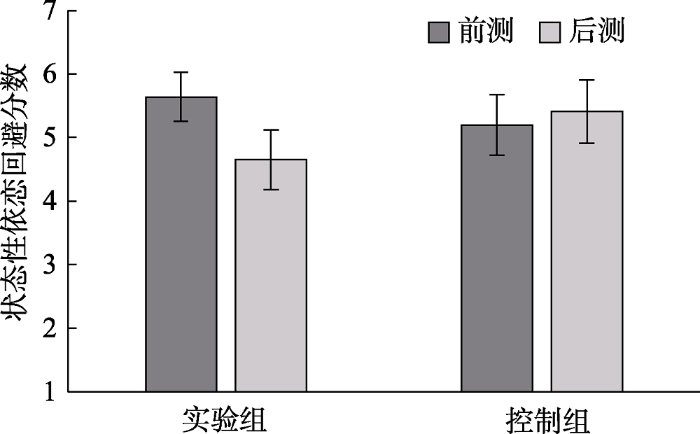

在状态性依恋安全上, 组别主效应显著, F(1,44) = 4.37, p = 0.04, 偏η2 = 0.09; 测量时间主效应显著, F(1.44) = 10.21, p = 0.003, 偏η2 = 0.19; 测量时间和组别的交互效应显著, F(1.44) = 19.62, p < 0.001, 偏η2 = 0.31 (如图2)。简单效应分析的结果表明, 实验组后测的状态性依恋安全要显著高于前测, t(22) = 4.61, p < 0.001, d = 0.90, 而在控制组条件下, 前后测的状态性依恋安全之间无显著差异; 此外, 前测的评定实验组控制组无显著差异, 而后测评定上实验组的状态性依恋安全要显著高于控制组, t(44) = 4.06, p < 0.001, d = 1.22。在状态性依恋焦虑维度上, 测量时间主效应不显著, F(1,44) = 0.05, p = 0.82; 组别的主效应不显著, F(1,44) = 0.80, p = 0.38; 交互效应不显著, F(1,44) = 0.62, p = 0.44。在依恋回避维度上, 测量时间的主效应不显著, F(1,44) = 2.01, p = 0.16; 组别的主效应不显著, F(1,44) = 0.07, p = 0.80; 存在显著的测量时间和组别的交互效应, F(1.44) = 4.79, p = 0.03, 偏η2 = 0.10 (如图3)。简单效应分析发现, 实验组条件下, 后测的状态性依恋回避要显著低于前测, t(22) = 2.91, p = 0.008, d = 0.86, 而在控制组条件下,前后测的状态性依恋回避之间无显著差异; 此外, 前测的评定实验组控制组无显著差异, 而后测评定上实验组的状态性依恋回避要低于控制组, 但差异并不显著。

图2

图3

随后, 我们控制了个体的依恋个体差异, 即将个体的依恋回避和依恋焦虑作为协变量再次进行方差分析, 结果表明, 除状态性依恋回避的交互效应变为边缘显著外(p = 0.066), 其他结果均同未控制条件的分析结果一致。因存在多个因变量, 采用Bonferrini方法进行多重比较校正, 将显著性水平设置为0.05/6 = 0.0083, 除在状态性依恋回避维度的结果变得不显著(p = 0.03), 在预期伴侣反应性及状态性依恋安全变量的显著性结果不变。

3.3 实验组控制组前后测差值的相关

研究分析了预期伴侣反应性前后测差值与状态依恋安全前后测差值的相关, 结果表明, 预期伴侣反应性的增加与状态性依恋安全的增加量之间呈显著的正相关关系(p = 0.03), 与状态性依恋焦虑(p = 0.06)和状态性依恋回避的降低之间边缘显著负相关(p = 0.08) (表3)。表明了伴侣反应性的通达与依恋安全感获得间的关联。同时, 在情境困境感受的变化上, 也发现了困境感受差异和支持寻求意愿的变化、状态依恋焦虑的变化显著正相关(ps < 0.001)。

表3 结果变量前后测差值的相关(N = 46)

| 变量 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 困境感受差异 | |||||

| 2. 寻求意愿差异 | 0.55*** | ||||

| 3. 预期伴侣反应性差异 | -0.14 | 0.05 | |||

| 4. 状态安全差异 | -0.04 | 0.21 | 0.32* | ||

| 5. 状态焦虑差异 | 0.48*** | 0.19 | -0.28 | -0.20 | |

| 6. 状态回避差异 | 0.10 | -0.10 | -0.26 | -0.06 | 0.17 |

注:*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

4 讨论

研究采用实验法, 考察情节模拟是否可以帮助个体获得依恋安全感。结果表明, 当个体处于困境情境时, 依恋相关的情节模拟能够显著增加预期的伴侣反应性, 并且带来状态性依恋安全感的提升。研究结果支持了情节模拟在依恋系统中的作用, 即依恋相关的情节模拟可以通达伴侣反应和可得的信息, 帮助个体获得依恋安全感。

4.1 情节模拟对预期伴侣反应性的影响

在本研究中我们可以看到, 依恋相关的情节模拟可以帮助个体通达伴侣反应性的信息。具体而言, 相比控制组, 情节模拟组被试预期伴侣有更高的反应性, 即依恋相关的情节模拟可以增加预期的伴侣反应性。这与已有研究中认为的, 情节模拟可以使得个体认为事件更有可能会发生或更加真实的观点一致(Taylor & Schneider, 1989)。Szpunar和Schacter (2013) 也指出, 模拟一个假定的事件可以提供更多关于事件可能发生时候的信息, 使得事件的场景更为真实和具体, 因此可以提高主观上对事件发生可能性的判断。例如, 在“你第一次约自己的好朋友们和男朋友一起吃饭, 想让男朋友在大家面前留个好印象, 但是男朋友一直在玩手机”这一困境中, 被试会产生如“我坐在他的旁边, 然后偷偷碰了一下他, 有点生气地让他不要再玩手机了。他接收到了我的请求, 有点不好意思, 慢慢地放下了手机, 开始吃饭聊天了。后来男朋友由于一个他们共同感兴趣的话题和他们聊了起来, 并解释刚刚在看手机是因为工作上的一点紧急情况, 请求大家的理解……”的情节模拟的内容, 这一模拟会使得个体判断在真实的困境中, 伴侣会采取预期的“放下手机”、“寻找共同感兴趣的话题”、“解释”和“请求原谅”等支持行为, 进而增加预期伴侣反应性的判断。因此, 积极建构困境情境下伴侣给予自己帮助支持的情节模拟, 可以增加在此事件伴侣真实给予自己帮助和支持的信心, 即让个体相信在真实发生类似的情境之下, 伴侣会表现出与模拟一致的高反应性的行为。

4.2 情节模拟对依恋安全感的影响

从依恋安全感的获得角度来看, 本研究发现依恋相关的情节模拟可以提升安全感。依恋控制系统模型强调的是依赖于伴侣在困境中的问题应对机制, 是一个目标导向的问题解决过程。在该系统中, 获得依恋安全感是主要的目标(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016)。依恋控制系统指出, 当个体面对威胁时, 会采取情绪聚焦的应对, 即识别和寻找情绪支持; 也会采取问题聚焦的应对, 即寻找工具性的支持并解决问题(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016)。依恋理论认为这两种应对机制以安全基地脚本的形式表征在内部工作模式之中, 在困境中对个体行为策略的选择与问题应对方式产生直接影响(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003)。但依恋控制系统却忽略了情节模拟的作用。情节模拟具有积极的建构特性, 有助于各种目标导向行为(Schacter, 2012), 当个体面临威胁时, 会积极进行情节模拟去建构问题解决。无论是情绪聚焦的应对, 还是问题聚焦的应对, 都可以从情节模拟中获益。

研究发现采用情节模拟的方式可以激发个体的动机去朝向问题解决的积极结果(Taylor, Pham, Rivkin, & Armor, 1998); 对未来的情节模拟提供了预期潜在障碍的机会并且可以让个体使用已有信息去为行为做出计划(Rivkin & Taylor, 1999)。Brown, Macleod, Tata和Goddard (2002)发现, 当个体对将来可能引发焦虑的事件进行积极结果的情节模拟时, 可以消除对未来事件的担忧。因此, 当个体积极建构寻求帮助的策略(如前文示例中的“碰一下伴侣”、“表达出生气”及“要求伴侣改变”等)和对应伴侣的行为计划(如前文示例中“放下手机”、“寻找共同感兴趣的话题”、“解释”和“请求原谅”)时, 会增加个体采取相应的行为的可能性, 增加问题应对的信心, 增强预期伴侣反应性, 进而获得安全感。有研究发现模拟解决目的-手段问题以及模拟消极事件的积极结果可以增加个体对消极事件的积极再评价并提升主观幸福感(Jing et al., 2016, 2017)。本研究和这些研究结果一致并且将其扩展到关系相关的情节模拟, 结果表明情节模拟有利于个体在困境中依赖伴侣进行积极应对, 有助于安全感获得这一目标导向的行为。

4.3 情节模拟对情境中困境感受及寻求支持意愿的影响

然而, 本研究并未发现这种模拟可以降低对事件困境感受的评价以及增加向伴侣寻求支持的意愿。这与已有关于情节模拟可以增加个体对消极事件积极再评价的研究(Jing et al., 2017), 以及模拟帮助他人可以增加帮助意愿的研究(Gaesser & Schacter, 2014)并不一致。对于困境感受的评价, 可能与事件情境的内容有关, 事件都是关系中的高困境感受的事件, 这种恋爱相关的高困境感受可能较难短时间改变。而对于向伴侣寻求支持的意愿而言, 从被试填写的情节模拟的文本来看, 在模拟过程中产生的向伴侣寻求支持的步骤较少, 更多的是伴侣给予自己帮助或支持相关的步骤, 因此没有体现出模拟的效应。

4.4 情节模拟在依恋控制系统模型中的作用

依据依恋控制系统模型所论述, 当个体感觉到威胁时会向内在依恋对象寻求亲近, 如果依恋对象可得或具有高的反应性, 那么个体将会获得安全感(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003)。研究中发现伴侣反应性提升与依恋安全感提升间的显著相关, 支持了依恋控制系统模型中认为的伴侣可得与反应的通达可以帮助个体获得依恋安全感的观点, 也表明了情节模拟确实可以在依恋系统中发挥重要作用。本研究的研究结果扩展了依恋控制系统模型的内容, 为控制系统模型增加了情节模拟这一新的依恋安全感的获得路径。

传统的依恋理论认为, 伴侣可得与反应性信息来源于个体安全基地脚本的通达, 安全依恋的个体拥有连贯的安全基地脚本, 并且更擅长使用安全基地脚本来应对困境, 因此他们更容易在困境问题中采用亲近寻求的方式来解决问题并获得依恋安全感(Mikulincer et al., 2009)。然而, 这一对依恋控制系统模型的观点和认识忽略了依恋控制系统模型的情境依赖性以及依恋安全的可变性。依恋控制系统模型既对个体人格或特质因素敏感, 也对特定情境具有敏感性, 这意味着特定情境下依恋安全感的获得不能完全归因于个体的依恋风格或依恋取向, 即便是依恋不安全的个体也可能在特定的情境中获得依恋安全感, 采取相对积极的问题应对方式(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016)。由于安全基地脚本具有相对稳定的特点(Waters & Waters, 2006), 将依恋安全感的获得完全归因为是安全基地脚本的通达难以解释依恋控制系统的情境依赖性。

本研究结果在控制了个体的特质依恋之后, 仍能观察到情节模拟的效应, 表明了情节模拟具有其独特作用。其实, 依恋理论也指出, 依恋内部工作模式允许个体去预测未来和伴侣的可能交往情况并调整亲近寻求的尝试。情节模拟强调在特定情境下的积极建构与问题解决, 这与依恋内部工作模式的定义更为相符。Bowlby最初强调依恋内部工作模式的“工作”二字, 便是指的内部工作模式可以允许个体去形成关于未来情境的“具身模拟”并积极寻求问题解决过程(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016)。由此可见, 关于情节模拟的研究实质上可以用来解释依恋控制系统的情境依赖性, 能够进一步明确依恋控制系统模型的作用机制。

综上, 本研究对依恋控制系统模型提出一条安全感获得的补充路径, 即除脚本加工外, 建构依恋相关的情节模拟可以通达伴侣可得与反应性的信息, 进而帮助个体获得依恋安全感。研究结果为日常生活带来启示:在遇到困境时, 多进行伴侣支持的情节模拟, 即想象如何向伴侣寻求帮助, 以及如何在伴侣的支持和帮助下解决当下的困境, 将有助于个体应对困境, 提升安全感。未来研究可以从情节模拟的角度来进行依恋安全的干预。情节模拟的建构特性意味着即使依恋不安全的个体, 或者不具备相似经验的个体也可以采用该方式在特定的困境中获得安全感。此外, 还可以通过干预情节模拟的方式来增强安全感的提升效果。已有研究发现, 越详细的情节模拟越有效(Jing et al., 2016, 2017), 因此可以通过增加情节模拟的细节丰富性来增强情节模拟的效果。

4.5 不足与展望

本研究的不足及未来研究的方向具体包含以下几个方面:

首先, 在测量方式上, 为了更加敏感地探测个体在每个特定情境下依恋安全感的波动, 本研究采用单个项目, 而不是采用整个问卷来测量个体的依恋安全感, 这一测验方式可能在测量学上较为简单, 不如多项目问卷更能包含依恋安全感的含义。但本研究增加了多个试次的测量, 并选取每个维度下载荷最高的题项, 可以在一定程度上保证单个题项的信效度。未来研究可适当增加测量项目数量来进行检验; 此外, 本研究因变量的测量主要采用了自我报告的测量方式, 未来研究可以结合一些生理指标, 如皮质醇水平, 或真实的伴侣互动情境去考察情节模拟在依恋系统中的作用。

其次, 本研究基于依恋控制系统模型, 从情节模拟通达伴侣反应性的角度, 提供了一种对个体如何获得依恋安全感的新的解释。对于这一获得依恋安全感的方式的机制是怎样的, 还需要进一步研究来探讨。例如, 是否是由于这一情节模拟可以增加伴侣之间的沟通和反思, 造成了更好的问题解决, 进而增加依恋安全感, 亦或是情节模拟增加了个体认为事件真实发生的可能性, 增强了个体问题应对的信心等。

再次, 虽然当前研究在控制了依恋个体差异后, 仍能观察到情节模拟的作用。但不可否认的是, 依恋个体差异可能会影响到情节模拟过程。研究指出, 情节模拟的建构会依赖于个体的图式(Berntsen & Bohn, 2010), 依恋作为一种关系的图式, 可能会影响到个体如何构建关系相关的情节模拟。相关的研究发现, 依恋会影响到情节模拟的细节丰富性(Cao, Madore, Wang, & Schacter, 2018)。依恋个体差异还与未来定向的加工, 例如情绪预期(affective forecasting) (Tomlinson, Carmichael, Reis, & Aron, 2010)、预期未来的关系满意度(Whitaker, Beach, Etherton, Wakefield, & Anderson, 1999)以及在假定的依恋关系中是否能进行有利于关系的选择(Vicary & Fraley, 2007)等存在显著相关。然而, 尚未有研究针对依恋系统的工作方式探讨依恋个体差异对情节模拟的影响, 也尚未探讨情节模拟的差异是否会导致安全感上也存在差异。未来研究可以对此进行更加深入的探讨。

最后, 依恋的个体差异可能会影响从情节模拟中获得安全感的难易程度。安全依恋的个体更易通达伴侣支持相关的情节记忆(Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016), 而建构性情节模拟假说认为, 个体的情节记忆是其进行情节模拟的素材(Schacter & Addis, 2007)。那么, 这意味着在自然条件下, 安全依恋的个体更易于去提取伴侣支持相关的情节记忆来进行情节模拟, 并从而获得依恋安全感。但本研究中的情节模拟并非自发状态, 而是在强制要求条件下进行的。因此, 未来研究可以进一步关注在自然条件下依恋个体差异在情节模拟影响安全感获得中的作用。

5 结论

本研究发现, 依恋相关的情节模拟可以增加个体在困境中预期的伴侣反应性和状态性的依恋安全感。研究结果支持了情节模拟在依恋系统中的作用, 表明除安全基地脚本的作用外, 依恋相关的情节模拟也可以通达伴侣反应和可得信息, 帮助个体获得依恋安全感。

参考文献

I'll keep you in mind: The intimacy function of autobiographical memory

Increasing implicit self-esteem through classical conditioning

DOI:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00708.x

URL

PMID:15200636

[本文引用: 1]

Implicit self-esteem is the automatic, nonconscious aspect of self-esteem. This study demonstrated that implicit self-esteem can be increased using a computer game that repeatedly pairs self-relevant information with smiling faces. These findings, which are consistent with principles of classical conditioning, establish the associative and interpersonal nature of implicit self-esteem and demonstrate the potential benefit of applying basic learning principles in this domain.

Frequency, characteristics, and perceived functions of emotional future thinking in daily life

Remembering and forecasting: The relation between autobiographical memory and episodic future thinking

Rumination and overgeneral autobiographical memory as mediators of the relationship between attachment and depression

Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview

Internal working models in attachment relationships: Elaborating a central construct in attachment theory

Worry and the simulation of future outcomes

Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples

Remembering the past and imagining the future: Attachment effects on production of episodic details in close relationships

Repeated priming of attachment security influences later views of self and relationships

Cognitive representations of attachment: The content and function of working models

DOI:10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.603

URL

PMID:19424447

[本文引用: 2]

Historical developments regarding the attitude concept are reviewed, and set the stage for consideration of a theoretical perspective that views attitude, not as a hypothetical construct, but as evaluative knowledge. A model of attitudes as object-evaluation associations of varying strength is summarized, along with research supporting the model's contention that at least some attitudes are represented in memory and activated automatically upon the individual's encountering the attitude object. The implications of the theoretical perspective for a number of recent discussions related to the attitude concept are elaborated. Among these issues are the notion of attitudes as

Cognitive representations of attachment: The structure and function of working models

Perceptions of interparental conflict, romantic attachment, and psychological distress in college students

Frequency, characteristics and functions of future-oriented thoughts in daily life

DOI:10.1002/acp.v25.1 URL [本文引用: 1]

Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: Theory and evidence

DOI:10.1037/a0021367

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Researchers have used J. Bowlby's (1969/1982, 1973, 1980, 1988) attachment theory frequently as a basis for examining whether experiences in close personal relationships relate to the processing of social information across childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. We present an integrative life-span encompassing theoretical model to explain the patterns of results that have emerged from these studies. The central proposition is that individuals who possess secure experience-based internal working models of attachment will process in a relatively open manner a broad range of positive and negative attachment-relevant social information. Moreover, secure individuals will draw on their positive attachment-related knowledge to process this information in a positively biased schematic way. In contrast, individuals who possess insecure internal working models of attachment will process attachment-relevant social information in one of two ways, depending on whether the information could cause the individual psychological pain. If processing the information is likely to lead to psychological pain, insecure individuals will defensively exclude this information from further processing. If, however, the information is unlikely to lead to psychological pain, then insecure individuals will process this information in a negatively biased schematic fashion that is congruent with their negative attachment-related experiences. In a comprehensive literature review, we describe studies that illustrate these patterns of attachment-related information processing from childhood to adulthood. This review focuses on studies that have examined specific components (e.g., attention and memory) and broader aspects (e.g., attributions) of social information processing. We also provide general conclusions and suggestions for future research.

Episodic simulation and episodic memory can increase intentions to help others

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1402461111

URL

[本文引用: 3]

Empathy plays an important role in human social interaction. A multifaceted construct, empathy includes a prosocial motivation or intention to help others in need. Although humans are often willing to help others in need, at times (e.g., during intergroup conflict), empathic responses are diminished or absent. Research examining the cognitive mechanisms underlying prosocial tendencies has focused on the facilitating roles of perspective taking and emotion sharing but has not previously elucidated the contributions of episodic simulation and memory to facilitating prosocial intentions. Here, we investigated whether humans' ability to construct episodes by vividly imagining (episodic simulation) or remembering (episodic memory) specific events also supports a willingness to help others. Three experiments provide evidence that, when participants were presented with a situation depicting another person's plight, the act of imagining an event of helping the person or remembering a related past event of helping others increased prosocial intentions to help the present person in need, compared with various control conditions. We also report evidence suggesting that the vividness of constructed episodes-r ather than simply heightened emotional reactions or degree of perspective taking-supports this effect. Our results shed light on a role that episodic simulation and memory can play in fostering empathy and begin to offer insight into the underlying mechanisms.

Embodied simulation: From neurons to phenomenal experience

DOI:10.1007/s11097-005-4737-z

URL

[本文引用: 1]

The same neural structures involved in the unconscious modeling of our acting body in space also contribute to our awareness of the lived body and of the objects that the world contains. Neuroscientific research also shows that there are neural mechanisms mediating between the multi-level personal experience we entertain of our lived body, and the implicit certainties we simultaneously hold about others. Such personal and body-related experiential knowledge enables us to understand the actions performed by others, and to directly decode the emotions and sensations they experience. A common functional mechanism is at the basis of both body awareness and basic forms of social understanding: embodied simulation. It will be shown that the present proposal is consistent with some of the perspectives offered by phenomenology.]]>

Development and validation of a state adult attachment measure (SAAM)

DOI:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.12.009

URL

[本文引用: 1]

AbstractFor over two decades, individual differences in adult attachment style have been conceptualized and measured in terms of anxiety, avoidance, and security. During this time, the prevailing assumption has been that an adult’s attachment style is a relatively stable disposition, rooted in internal working models of self and relationship partners. These models are based on previous experiences in close relationships. Recent research, however, suggests that levels of attachment anxiety, avoidance, and security are also affected by situational factors. To capture temporary fluctuations in the sense of attachment security and insecurity we developed a state adult attachment measure (SAAM). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses yielded three reliable subscales measuring state levels of attachment-related anxiety, avoidance, and security. Additional studies demonstrated both convergent and discriminant validity of the new measure, and its sensitivity to a variety of experimental manipulations. Our discussion focuses on potential uses for the SAAM for both researchers and clinicians.]]>

Worrying about the future : An episodic specificity induction impacts problem solving, reappraisal, and well-being

Preparing for what might happen: An episodic specificity induction impacts the generation of alternative future events

DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2017.08.010

URL

PMID:28886407

[本文引用: 6]

A critical adaptive feature of future thinking involves the ability to generate alternative versions of possible future events. However, little is known about the nature of the processes that support this ability. Here we examined whether an episodic specificity induction - brief training in recollecting details of a recent experience that selectively impacts tasks that draw on episodic retrieval - (1) boosts alternative event generation and (2) changes one's initial perceptions of negative future events. In Experiment 1, an episodic specificity induction significantly increased the number of alternative positive outcomes that participants generated to a series of standardized negative events, compared with a control induction not focused on episodic specificity. We also observed larger decreases in the perceived plausibility and negativity of the original events in the specificity condition, where participants generated more alternative outcomes, relative to the control condition. In Experiment 2, we replicated and extended these findings using a series of personalized negative events. Our findings support the idea that episodic memory processes are involved in generating alternative outcomes to anticipated future events, and that boosting the number of alternative outcomes is related to subsequent changes in the perceived plausibility and valence of the original events, which may have implications for psychological well-being.

Measuring adult attachment: Chinese Adaptation of the ECR Scale

成人依恋的测量:亲密关系经历量表(ECR)中文版

Attachment theory and concern for others' welfare: Evidence that activation of the sense of secure base promotes endorsement of self-transcendence values

The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes

A model of attachment-system functioning and dynamics in adulthood

Attachment, caregiving, and altruism: Boosting attachment security increases compassion and helping

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.817

URL

PMID:16351370

[本文引用: 1]

Recent studies based on J. Bowlby's (1969/1982) attachment theory reveal that both dispositional and experimentally enhanced attachment security facilitate cognitive openness and empathy, strengthen self-transcendent values, and foster tolerance of out-group members. Moreover, dispositional attachment security is associated with volunteering to help others in everyday life and to unselfish motives for volunteering. The present article reports 5 experiments, replicated in 2 countries (Israel and the United States), testing the hypothesis that increases in security (accomplished through both implicit and explicit priming techniques) foster compassion and altruistic behavior. The hypothesized effects were consistently obtained, and various alternative explanations were explored and ruled out. Dispositional attachment-related anxiety and avoidance adversely influenced compassion, personal distress, and altruistic behavior in theoretically predictable ways. As expected, attachment security provides a foundation for care-oriented feelings and caregiving behaviors, whereas various forms of insecurity suppress or interfere with compassionate caregiving.

The effects of implicit and explicit security priming on creative problem solving

DOI:10.1080/02699931.2010.540110

URL

PMID:21432691

[本文引用: 1]

Attachment theory is a theory of affect regulation as it occurs in the context of close relationships. Early research focused on regulation of emotions through maintenance of proximity to supportive others (attachment figures) in times of need. Recently, emphasis has shifted to the regulation of emotion, and the benefits of such regulation for exploration and learning, via the activation of mental representations of attachment figures (security priming). We conducted two studies on the effects of implicit and explicit security priming on creative problem solving. In Study 1, implicit security priming (subliminal presentation of attachment figures' names) led to more creative problem solving (compared with control conditions) regardless of dispositional attachment anxiety and avoidance. In Study 2, the effects of explicit security priming (recalling experiences of being well cared for) were moderated by anxiety and avoidance. We discuss the link between attachment and exploration and the different effects of implicit and explicit security priming.

What's inside the minds of securely and insecurely attached people? The secure-base script and its associations with attachment-style dimensions

DOI:10.1037/a0015649

URL

PMID:19785482

[本文引用: 2]

In 8 studies the authors explored the procedural knowledge (secure-base script; H. S. Waters & E. Waters, 2006) associated with secure attachment (i.e., low scores on attachment anxiety and avoidance). The studies assessed the accessibility, richness, and automaticity of the secure-base script and the extent to which it guided the processing of attachment-relevant information. Secure attachment (lower scores on anxiety and avoidance) was associated with greater secure-base

The effects of mental simulation on coping with controllable stressful events

The effect of attachment orientation priming on pain sensitivity in pain-free individuals

Attachment style differences in the processing of attachment-relevant information: Primed-style effects on recall, interpersonal expectations, and affect

Adaptive constructive processes and the future of memory

DOI:10.1037/a0029869

URL

PMID:23163437

[本文引用: 2]

Memory serves critical functions in everyday life but is also prone to error. This article examines adaptive constructive processes, which play a functional role in memory and cognition but can also produce distortions, errors, and illusions. The article describes several types of memory errors that are produced by adaptive constructive processes and focuses in particular on the process of imagining or simulating events that might occur in one's personal future. Simulating future events relies on many of the same cognitive and neural processes as remembering past events, which may help to explain why imagination and memory can be easily confused. The article considers both pitfalls and adaptive aspects of future event simulation in the context of research on planning, prediction, problem solving, mind-wandering, prospective and retrospective memory, coping and positivity bias, and the interconnected set of brain regions known as the default network.

The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: Remembering the past and imagining the future

DOI:10.1098/rstb.2007.2087

URL

PMID:17395575

[本文引用: 1]

Episodic memory is widely conceived as a fundamentally constructive, rather than reproductive, process that is prone to various kinds of errors and illusions. With a view towards examining the functions served by a constructive episodic memory system, we consider recent neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies indicating that some types of memory distortions reflect the operation of adaptive processes. An important function of a constructive episodic memory is to allow individuals to simulate or imagine future episodes, happenings and scenarios. Since the future is not an exact repetition of the past, simulation of future episodes requires a system that can draw on the past in a manner that flexibly extracts and recombines elements of previous experiences. Consistent with this constructive episodic simulation hypothesis, we consider cognitive, neuropsychological and neuroimaging evidence showing that there is considerable overlap in the psychological and neural processes involved in remembering the past and imagining the future.

Episodic simulation of future events: Concepts, data, and applications

Episodic future thinking: Mechanisms and functions

DOI:10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.06.002

URL

PMID:29130061

[本文引用: 1]

Episodic future thinking refers to the capacity to imagine or simulate experiences that might occur in one's personal future. Cognitive, neuropsychological, and neuroimaging research concerning episodic future thinking has accelerated during recent years. This article discusses research that has delineated cognitive and neural mechanisms that support episodic future thinking as well as the functions that episodic future thinking serves. Studies focused on mechanisms have identified a core brain network that underlies episodic future thinking and have begun to tease apart the relative contributions of particular regions in this network, and the specific cognitive processes that they support. Studies concerned with functions have identified several domains in which episodic future thinking produces performance benefits, including decision making, emotion regulation, prospective memory, and spatial navigation.

Navigating into the future or driven by the past

DOI:10.1177/1745691612474317

URL

PMID:26172493

[本文引用: 2]

Prospection (Gilbert & Wilson, 2007), the representation of possible futures, is a ubiquitous feature of the human mind. Much psychological theory and practice, in contrast, has understood human action as determined by the past and viewed any such teleology (selection of action in light of goals) as a violation of natural law because the future cannot act on the present. Prospection involves no backward causation; rather, it is guidance not by the future itself but by present, evaluative representations of possible future states. These representations can be understood minimally as

Get real: Effects of repeated simulation and emotion on the perceived plausibility of future experiences

A taxonomy of prospection: Introducing an organizational framework for future-oriented cognition

Harnessing the imagination: Mental simulation, self-regulation, and coping

DOI:10.1037//0003-066x.53.4.429

URL

PMID:9572006

[本文引用: 1]

Mental simulation provides a window on the future by enabling people to envision possibilities and develop plans for bringing those possibilities about. In moving oneself from a current situation toward an envisioned future one, the anticipation and management of emotions and the initiation and maintenance of problem-solving activities are fundamental tasks. In the program of research described in this article, mental simulation of the process for reaching a goal or of the dynamics of an unfolding stressful event produced progress in achieving those goals or resolving those events. Envisioning successful completion of a goal or resolution of a stressor--recommendations derived from the self-help literature--did not. Discussion centers on the characteristics of effective and ineffective mental simulations and their relation to self-regulatory processes.

Coping and the simulation of events

Affective forecasting and individual differences: Accuracy for relational events and anxious attachment

DOI:10.1037/a0018701

URL

PMID:20515233

[本文引用: 1]

We examined whether accuracy of affective forecasting for significant life events was moderated by a theoretically relevant individual difference (anxious attachment), with different expected relations to predicted and actual happiness. In 3 studies (2 cross-sectional, 1 longitudinal), participants predicted what their happiness would be after entering or ending a romantic relationship. Consistent with previous research, people were generally inaccurate forecasters. However, inaccuracy for entering a relationship was significantly moderated by anxious attachment. Predictions were largely unrelated to anxious attachment, but actual happiness was negatively related to attachment anxiety. Moderation for breaking up showed a similar but less consistent pattern. These results suggest a failure to account for one's degree of anxious attachment when making affective forecasts and show how affective forecasting accuracy in important life domains may be moderated by a focally relevant individual difference, with systematically different associations between predicted and actual happiness.

Choose your own adventure: Attachment dynamics in a simulated relationship

DOI:10.1177/0146167207303013

URL

PMID:17933741

[本文引用: 1]

According to attachment theory, insecure individuals respond to events in their romantic relationships in ways that sometimes can be destructive. The objective of this research was to examine how these responses may accumulate over repeated interactions to influence the quality of the relationship. Across three studies, participants were presented with a

Attachment effects on memory of painful information over time: From the perspective of narrative anylasis

(Unpublished doctorial dissertation).

依恋系统对心痛事件记忆的影响及时程作用:内容分析的视角

(博士学位论文).

The attachment working models concept: Among other things, we build script-like representations of secure base experiences

DOI:10.1080/14616730600856016

URL

PMID:16938702

[本文引用: 3]

Mental representations are of central importance in attachment theory. Most often conceptualized in terms of working models, ideas about mental representation have helped guide both attachment theory and research. At the same time, the working models concept has been criticized as overly extensible, explaining too much and therefore too little. Once unavoidable, such openness is increasingly unnecessary and a threat to the coherence of attachment theory. Cognitive and developmental understanding of mental representation has advanced markedly since Bowlby's day, allowing us to become increasingly specific about how attachment-related representations evolve, interact, and influence affect, cognition, and behavior. This makes it possible to be increasingly specific about mental representations of attachment and secure base experience. Focusing on script-like representations of secure base experience is a useful first step in this direction. Here we define the concept of a secure base script, outline a method for assessing a person's knowledge/access to a secure base script, and review evidence that script-like representations are an important component of the working models concept.

Attachment, self‐compassion, empathy, and subjective well‐being among college students and community adults

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00677.x

URL

PMID:21223269

[本文引用: 1]

Research on subjective well-being suggests that it is only partly a function of environmental circumstances. There may be a personality characteristic or a resilient disposition toward experiencing high levels of well-being even in unfavorable circumstances. Adult attachment may contribute to this resilient disposition. This study examined whether the association between attachment anxiety and subjective well-being was mediated by Neff's (2003a, 2003b) concept of self-compassion. It also examined empathy toward others as a mediator in the association between attachment avoidance and subjective well-being. In Study 1, 195 college students completed self-report surveys. In Study 2, 136 community adults provided a cross-validation of the results. As expected, across these 2 samples, findings suggested that self-compassion mediated the association between attachment anxiety and subjective well-being, and emotional empathy toward others mediated the association between attachment avoidance and subjective well-being.

Attachment and expectations about future relationships: Moderation by accessibility

Affective forecasting: Knowing what to want