1 引言

作为表达和传递情绪信息的载体, 面孔表情和身体语言在人类的社会交往中起着重要作用。情绪识别问题, 即从面孔或身体姿势中推断出正确的情绪信息, 始终是情绪领域研究的热点。根据情绪维度观, 情绪信息包括效价、强度、唤醒度三个维度(Mehrabian & Russell, 1974)。而情绪识别主要指的是, 对情绪效价(或愉悦程度)的区分。一般而言, 表情的强度越大, 越容易被识别(Ekman, 1993), 因为高强度表情使得脸部肌肉的区分变大(Ekman, 1993)。而且, 高强度刺激位于情绪效价轴(“积极-消极”或“愉悦-不愉悦”)的两端位置(Carroll & Russell, 1996), 更容易被判断出其效价的正性或负性。

然而, 实际生活情景中, 表情的区分并非完全按照以上规律。Aviezer, Trope和Todorov (2012)发表在《Science》上的研究指出, 来源于真实生活的高强度面孔表情, 与基本表情的情绪识别存在不同。他们选取了网球比赛中运动员赢分和输分后的面孔表情或者身体表情, 让被试判断图片的效价(9点评分, 1为非常消极, 5为中性, 9为非常积极)。结果发现, 通过面部表情很难区分赢分与输分图片效价的正负; 相反, 通过身体表情或者完整图片(同时包括面孔和身体的信息)却可以有效地区分。同时, Aviezer等人(2012)还采用其它高强度正性情景(如性高潮)或负性情景(如葬礼、乳头穿刺)中的面孔图片, 也发现了, 从面孔表情上无法区分出效价。当这些面孔图片与运动员赢分和输分后的身体图片同时呈现时, 被试对面孔表情的效价判断倾向于身体表现出的情绪, 也就是, 根据身体情绪判断面孔的情绪。因此作者指出, 在高强度情绪背景下, 身体语言能提供更有效的情绪信息, 辅助面孔情绪的判断。

探讨实验室外的人们真实情绪反应, 具有重要的意义, 不仅因为关注了现实生活中的理论问题, 还揭示了人类情绪的复杂性和多样性。已有的研究, 实验材料多为情绪库中的面孔或身体(Gu, Mai, & Luo, 2013; Wang et al., 2016), 这些图片多为演员表演而成, 而且图片类型主要是一些典型情绪:快乐、愤怒、恐惧、悲伤、厌恶和惊讶。Aviezer等人(2012)的研究表明, 对运动员赢分或输分图片的情绪识别, 与人们所通常认为的“面孔表情可以提供个体的情绪信息”的观点有一定的差别。欣赏体育比赛或观看比赛图片是很多人日常生活的一部分。本文期望对运动员输赢识别中的“面孔表情的低区分性”和“身体表情的高区分性”这一现象提供可能的原因解释。

本文关注的第一个问题, 验证中国运动员的表情是否也存在面孔效价的“非诊断性”和身体效价的区分性。Aviezer等人(2012)研究中, 图片材料主要为西方人的面孔表情和身体姿势。本文(实验1)采用与Aviezer等人(2012)相似的实验程序, 唯一的区别在于实验材料为中国运动员的图片, 选取中国运动员在高水平比赛中(包括网球、乒乓球、羽毛球)赢分或者失分后的图片, 让被试进行效价和强度评分。

本文关注的第二个问题, 进一步探讨运动员输赢识别中的“面孔表情的低区分性”和“身体表情的高区分性”这一现象产生的原因。Aviezer等人(2012)对面孔效价的“非诊断性”解释到, 高强度情绪可能在情绪体验上是相似的, 无论情景是正性的还是负性的。因此, 本研究猜测, 赢分或输分面孔可能含有相同效价的情绪内容, 导致二者效价的区分不明显。相反地, 赢分身体和输分身体可能含有不同效价的情绪内容, 导致二者效价的区分比较容易。因此, 了解图片传递的情绪内容, 或许可以为面孔效价的“非诊断性”和身体效价的高区分性提供解释。已有的研究多从面孔肌肉动作的角度, 来分析面孔图片传递的情绪。Matsumoto和Willingham (2006)曾对2004年雅典奥运会柔道比赛中胜利者和失败者的面孔表情进行了分析, 采用面部表情编码系统(Facial Affect Coding System, FACS) (Ekman & Friesen, 1978)分析肌肉活动。结果发现, 胜利者最显著的情绪为高兴, 失败者的情绪比较复杂和多样化, 传递着悲伤、厌恶和恐惧等情绪。Aviezer等(2015)同样采用面部表情编码系统, 对网球运动员赢分或输分后的面孔表情进行了分析, 结果发现了一个规律:相比输分者, 赢分者呈现出更多的脸部动作, 如张嘴、笑、眼部肌肉收缩等。研究者将这一规律告诉了被试, 让他们再次对赢分和输分的面孔做出效价区分, 结果发现, 被试仍然无法区分开来面孔效价的正负性。那么, 在被试的眼中, 赢分和输分面孔到底传递着什么样的情绪内容?面孔与身体传递的情绪内容是否相同?

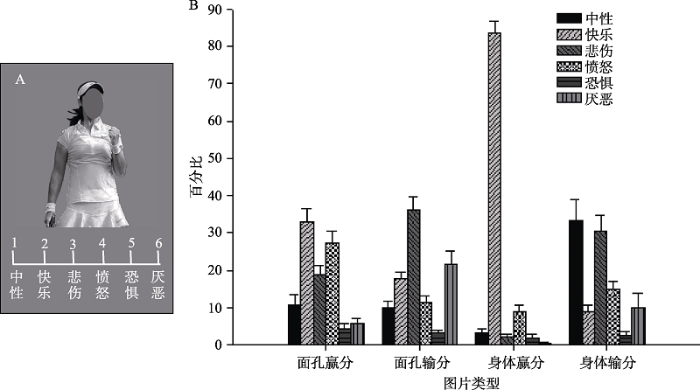

实验2的目的在于, 分析赢分和输分图片传递的情绪内容。研究中, 要求被试对图片的情绪类型进行选择(中性、快乐、悲伤、愤怒、恐惧、厌恶)。选择以上6种类型的情绪, 主要有两个方面的原因。第一, Ekman和Friesen (1969)归纳的6种基本的面部表情(快乐、愤怒、恐惧、悲伤、厌恶和惊讶)是复杂情绪发生、发展的基础(Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987)。第二, Matsumoto和Willingham (2006)采用面孔编码系统分析胜利和失败者的表情时, 微笑、悲伤、厌恶、恐惧、中性是出现频率最多的表情。因此, 综合以上观点, 本研究最终选择了中性、快乐、悲伤、愤怒、恐惧、厌恶共6种情绪, 让被试进行六选一的选择, 判断出图片的主导情绪。通过分析各类情绪所占的百分比, 可以比较面孔和身体表情传递情绪的不同。

本文关注的第三个问题, 探讨赢分和输分后的面孔表情和身体表情识别的神经机制, 为行为学表现寻找脑科学证据。在行为上要求被试分别对远动员赢分和失分后的面孔和身体图片做情绪分类(正性或负性), 通过两类反应所占的比率考查面孔表情和身体姿势对赢分图片与输分图片区分性的影响, 同时采用事件相关电位(Event-Related Potential, ERP)技术比较面孔表情与身体姿势的加工时程。ERP技术的时间分辨率达到1 ms, 而且不同的ERP成分反映的心理意义不同, 是用来研究面孔表情和身体姿势加工机制的重要工具。

相比身体语言神经机制的研究, 面孔表情神经机制的研究开展的比较早(Adolphs, 2002), 许多有价值的关于人类情绪加工的观点来源于对面孔表情的研究(de Gelder, 2006)。例如, 人们能够比较快速地识别面孔情绪, 杏仁核在恐惧面孔出现后的30 ms就产生反应(Luo, Holroyd, Jones, Hendler, & Blair, 2007; Luo, Holroyd, et al., 2010)。事件相关电位(ERP)的相关研究发现, 在刺激呈现后的100 ms左右, 负性面孔(尤其是恐惧面孔)比中性面孔诱发更大的枕叶P1成分(Luo, Feng, He, Wang, & Luo, 2010; Pourtois, Grandjean, Sander, & Vuilleumier, 2004)。研究者认为, P1成分反映了情绪面孔的自动化加工或快速加工。刺激呈现后170 ms左右的N170成分与面孔的结构编码有关, 面孔比非面孔刺激(如:汽车、房子、手)诱发更大的N170波幅(Bentin, Allison, Puce, Perez, & McCarthy, 1996)。近期研究表明N170可能敏感于情绪面孔的探测。例如, 恐惧面孔比中性面孔诱发了更负的N170成分(Blau, Maurer, Tottenham, & McCandliss, 2007; Leppänen, Moulson, Vogel-Farley, & Nelson, 2007; Pegna, Darque, Berrut, & Khateb, 2011; Schyns, Petro, & Smith, 2007)。然而, 也存在不一致的声音, 有研究发现N170与情绪面孔的加工也可能无关(Eimer, Kiss, & Holmes, 2008; Kiss & Eimer, 2008)。在200~300 ms左右位于枕颞区的早期后部负电位(Early Posterior Negativity, EPN), 也受到面孔情绪的影响(侠牧, 李雪榴, 叶春, 李红, 2014)。研究发现, 情绪面孔比中性面孔诱发更负的EPN波幅(Pegna, Landis, & Khateb, 2008; Schupp, Junghöfer, Weike, & Hamm, 2004)。对于300 ms之后的晚期正成分(Late Positive Potential, LPP), 负性表情比正性表情诱发的波幅更大(Hietanen & Astikainen, 2013; Wild-Wall, Dimigen, & Sommer, 2008)。

相比较而言, 身体语言的研究近10年才兴起(de Gelder, 2006)。与面孔一样, 身体动作与手势同样可以表达情绪信息。面孔主要依赖内部特征(嘴、眼睛、眉毛)传递情绪, 而身体可以依赖其外部框架传递情绪, 可以使人在更远的距离上判断其情绪信息(de Gelder & Hortensius, 2014)。身体的情绪信息可以被人类快速识别, 表现在恐惧身体比中性身体诱发更正的P1波幅(张丹丹, 赵婷, 柳昀哲, 陈玉明, 2015)。甚至, 当面孔与身体情绪信息不匹配时, 在P1阶段能被大脑探测到这一不匹配信息(Meeren, van Heijnsbergen, & de Gelder, 2005)。在随后的加工阶段, 未发现N170波幅受到身体表情的影响(Stekelenburg & de Gelder, 2004; 张丹丹等, 2015)。对于晚期LPP成分, 恐惧身体比中性身体诱发了更正的波幅(张丹丹等, 2015)。

在本文实验3中, 我们将采用ERP技术探讨赢分和输分后的面孔表情和身体表情识别的神经机制, 研究赢分和输分后的面孔表情与赢分和输分后的身体表情在各个加工阶段脑内加工进程的异同, 为实验1及实验2所发现的行为学表现寻找脑科学证据。

根据已有文献提供的证据(Matsumoto & Willingham, 2006; Aviezer et al., 2012), 本研究对三部分实验结果提出以下预期:1) 实验1预期观测到与Aviezer等人相似的结果:身体比面孔能够提供更有效的效价区分信息; 2)实验2中, 面孔可能含有多种类型的情绪, 赢分面孔和输分面孔条件下可能含有一些相同效价的情绪内容, 既包括正性类型的情绪内容(如快乐), 也包括一些负性类型的情绪内容(如悲伤、厌恶等), 导致对面孔效价的判断无法做出统一的归类(是正性还是负性); 相反地, 身体传递的效价信息可能更为明确, 赢分身体更多地被知觉为正性类的情绪, 输分身体更多地被知觉为负性类的情绪, 因此对身体效价的区分可能相对容易; 3)实验3中, 如前所述(Zhang et al., 2014; 侠牧等, 2014), P1成分反映了情绪信息的自动加工或快速加工, N170成分反映了对客体的结构编码, EPN反映了对情绪信息的选择性注意, LPP成分反映了情绪的高级认知加工和精细加工。如果与Aviezer等人(2012)的观点吻合, 身体比面孔信息能提供更明确的情绪信息, 则从脑电上观测到, 面孔的赢分与输分之间可能不存在差异, 而身体则存在情绪类型间的差异, 表现在多个ERP成分上, 如P1、N170、EPN、LPP。

2 实验1:运动员赢分与输分条件下面孔表情和身体姿势的效价和强度

2.1 实验目的

通过测量运动员赢分与输分条件下面孔表情和身体姿势的效价和强度, 验证中国运动员的表情是否存在面孔效价的“非诊断性”和身体效价的区分性。

2.2 研究方法

2.2.1 被试

19名在校大学生(女9名, 年龄范围17~22岁, 平均年龄为18.89岁, SD = 1.24岁), 被试均为右利手, 视力或矫正视力正常。所有被试均自愿参加实验, 实验结束后给予被试一定的报酬。

2.2.2 实验设计

刺激类型(面孔、身体)×情绪类型(赢、输)的被试内设计。因变量为图片的效价和肌肉强度评分。

2.2.3 实验材料和程序

运动员的情绪图片共60张(30张赢分和30张输分), 男女各半。图片的选取, 参考了Aviezer等人(2012)的方法:通过百度和谷歌搜索引擎, 关键词为“赢分反应”或“失分反应”, 与“乒乓球”或“羽毛球”或“网球”组合搜索, 共搜索到与主题相关的图片约300张左右。通过一定的筛选标准, 获得本文所使用的实验材料。图片筛选标准如下:图片包含面孔和身体信息; 图片清晰度较高; 比赛赢分或输分后短时间(约1分钟)内的情绪反应, 如果图片为比赛过程中的, 或者赢分或输分后较长时间后的情绪反应(如运动员与他人拥抱、庆祝等)均不入选。判断图片为赢分或输分后短时间内的情绪图片, 主要通过以下信息确认:1)运动员在比赛场地内; 2)手中仍握有乒乓球、羽毛球或网球; 3)查看图片来源网页记者对该图片的说明, 如“王浩赢分后反应”。对筛选的60张图片, 通过Photoshop软件, 将面孔部分从原图中抠出, 形成60张面孔图片; 以及用椭圆形灰色块遮住面部信息, 形成60张身体图片。刺激呈现在21寸的CRT显示器上(60 Hz刷新率)。被试距离屏幕大约100 cm。面孔图片的视角是为3.4°×3.4°, 身体图片的视角为5.7°×5.7°。

实验采用E-Prime软件(Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA)呈现刺激与收集行为反应数据。实验流程图见图1, 每个trial中, 实验刺激和下方的1~9评分量表同时呈现。下方的评分表, 分别为情绪愉悦度效价1~9判定表(1为非常消极, 2为消极, 3为比较消极, 4为轻微消极, 5为中性, 6为轻微积极, 7为比较积极, 8为积极, 9为非常积极)或者是强度效价1~9判定表(1为强度非常低, 5为中间值, 9为强度非常高)。在每个试次中, 要求被试从1~9中选择一个合适的数字对图片判断效价, 按键后, 再对同一图片选择1~9中合适的数字判断强度, 开始下一个试次。实验包括面孔识别和身体识别两部分, 每部分含有60个试次, 每张图片呈现2次, 图片随机呈现。

图1

图1

实验1流程图

注:A: 实验流程示例; B: 实验材料示例, 1为赢分面孔, 2为赢分身体, 3为赢分原始图片, 4为输分面孔, 5为输分身体, 6为输分原始图片

2.3 结果和分析

统计分析采用SPSS 17.0 (IBM, Somers, 美国)。被试对图片的效价和强度评分结果见图2。在效价判断任务中, 对效价评分进行刺激类型(身体vs.面孔)×情绪类型(赢分vs.输分)重复测量方差分析, 结果发现刺激类型的主效应显著, F(1,18) = 71.62, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.799, 身体的效价(平均数±标准误, 5.93 ± 0.17)高于面孔的效价(4.71 ± 0.15)。

情绪类型的主效应显著, F(1,18) = 124.95, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.874, 赢分图片的效价(6.45 ± 0.21)高于输分图片的效价(4.20 ± 0.13)。刺激类型与情绪类型的交互作用显著, F(1,18) = 14.50, p < 0.005, ηp2 = 0.446, 简单效应的分析发现, 无论是面孔, 还是身体, 赢分图片的效价均高于输分图片的效价(面孔:赢分5.57 ± 0.23, 输分 3.86 ± 0.13, p < 0.001; 身体:赢分7.33 ± 0.23, 输分 4.54 ± 0.20, p < 0.001)。本文对面孔条件和身体条件下输分与赢分之间的差异, 进行了配对样本T检验, 结果显示, t (18) = -3.81, p < 0.005, Cohen's d = 0.87。结果表明, 赢分与输分之间的效价差异在身体条件下更大(“赢分”-“输分”, 身体:2.79 ± 0.27, 面孔:1.70 ± 0.22)。说明中国运动员的赢分或输分表情, 既存在面孔效价的“诊断性”, 也存在身体效价的区分性, 但身体姿势对赢分和输分的效价区分性要大于面孔表情。

图2

在强度判断任务中, 对强度评分进行重复测量方差分析, 结果发现刺激类型的主效应不显著, F(1,18) = 0.68, p = 0.42。情绪类型的主效应显著, F(1,18) = 26.83, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.598, 赢分图片的强度(6.45 ± 0.28)高于输分图片的强度(5.27 ± 0.21)。刺激类型与情绪类型的交互作用显著, F(1,18) = 17.35, p < 0.005, ηp2 = 0.491, 简单效应的分析发现, 无论是面孔, 还是身体, 赢分图片的强度均高于输分图片的强度(面孔:赢分6.10 ± 0.27, 输分5.42 ± 0.27, p < 0.01; 身体:赢分6.79 ± 0.36, 输分5.12 ± 0.22, p < 0.001)。本文对面孔条件和身体条件下, 输分与赢分之间的强度差异进行了配对样本t检验, 结果显示, t (18) =-4.17, p < 0.005。结果表明, 赢分与输分之间的强度差异在身体条件下更大(“赢分”-“输分”, 身体:1.67 ± 0.28, 面孔:0.68 ± 0.22)。说明面孔表情和身体姿势对中国运动员赢分或输分的表情强度均具有较好的区分性, 但身体姿势对赢分或输分强度区分性要大于面孔表情。

实验1结果表明, 在效价和强度两个维度上, 均可以将赢分和输分图片区分开来。与Aviezer等人(2012)研究的相同之处有两点:(1)身体图片可以提供有效的情绪信息, 相比输分图片, 赢分图片的效价更加积极, 肌肉强度更大, 验证了中国运动员的表情存在身体效价的区分性; (2)从强度维度上, 赢分面孔比输分面孔的强度更大。不同之处在于, Aviezer等人发现的面孔效价的“非诊断性”并未得到验证。本研究发现, 面孔传递的情绪效价信息并非没有区分性, 输分面孔比赢分面孔的评价更加消极, 表明中国运动员的面孔表情可以传递一定的输或赢的情绪信息。那么, 赢分图片与输分图片到底在传递什么样的情绪, 面孔和身体所传递的情绪是否有所差别, 实验2的行为实验将对该问题进行进一步的探讨。

3 实验2:运动员赢分和输分后面孔表情和身体姿势的情绪类型

3.1 实验目的

通过分析运动员赢分和输分后面孔表情和身体姿势的情绪类型, 探讨面孔表情效价的低区分性和身体表情效价的高区分性的原因。

3.2 研究方法

3.2.1 被试

16名在校大学生(女15名, 年龄范围18~21岁, 平均年龄为19.56岁, SD = 0.81岁), 被试均为右利手, 视力或矫正视力正常。所有被试均自愿参加实验, 试验结束后给予被试一定的报酬。

3.2.2 实验设计

刺激类型(面孔、身体)×情绪类型(赢、输)的被试内设计。因变量为图片的情绪类型的百分比。

3.2.3 实验材料和程序

实验材料与实验1相同。图3为实验2流程图, 每个trial中, 实验刺激和下方的1~6量表同时呈现。下方的量表, 分别为情绪类型和指定的按键(1-中性, 2-快乐, 3-悲伤, 4-愤怒, 5-恐惧, 6-厌恶。要求被试从1~6中选择一个合适的数字判断图片表达的情绪类型, 按键后图片消失, 开始下一个试次。实验共有两个部分, 第一部分实验材料为面孔图片, 第二部分实验材料为身体图片, 每部分含有60个试次, 每张图片呈现1次, 图片随机呈现。

图3

3.3 结果和分析

被试对图片情绪类型的判断结果见表1和图3。为了考察图片表达的情绪是否唯一或者多样化, 采用卡方检验分别对4种条件下(面孔赢分、面孔输分、身体赢分、身体输分)的6种情绪类型的百分比进行了比较。结果发现, 4种实验条件下卡方检验的结果均极其显著, ps < 0.001。结果表明, 被试在不同条件下感知到的情绪内容存在显著差异。面孔赢分条件下, 报告频率较高的(大于15%)的情绪依次为快乐(32.92%)、愤怒(27.29%)、悲伤(18.75%), 面孔输分条件下, 报告频率较高的的情绪依次为悲伤(36.04%)、厌恶(21.67%)、快乐(17.71%)。身体赢分条件下, 报告频率最高的的情绪为快乐(83.54%), 其它情绪类型所占百分比均小于9%。身体输分条件下, 报告频率较高的的情绪依次为中性(33.33%)、悲伤(30.42%)。

4种条件的比较分析发现, 赢分身体传递的情绪较为单一, 更高频率地被知觉为快乐。从行为上看, 胜利者的肢体动作常表现出举起的手臂, 紧握的拳头。其它三种条件下, 感知到情绪内容比较多样化。对于面孔刺激, 赢分和输分图片既感知到正性情绪(如快乐)也包含负性情绪(如愤怒、悲伤、厌恶)。当被试对面孔图片进行积极或消极的效价评价时, 赢分与输分之间的效价差异相对较小, 这为Aviezer等人(2012)研究中面孔对效价的“非诊断性”提供了可能的解释。相反地, 身体传递情绪类型较为单一, 赢分身体更多地被感知为积极情绪, 输分身体更多地被感知为悲伤和中性情绪, 从效价评分上看, 更容易得出赢分与输分效价得分的差异。

表1 不同实验条件下情绪类型判断的百分比 (平均数 ± 标准差)

| 条件 | 中性 | 快乐 | 悲伤 | 愤怒 | 恐惧 | 厌恶 | χ2 (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 面孔赢分 | 10.83 ± 10.24 | 32.92 ± 14.33 | 18.75 ± 10.47 | 27.29 ± 12.09 | 4.38 ± 5.10 | 5.83 ± 5.20 | 41.12 (5) | < 0.001 |

| 面孔输分 | 10.00 ± 7.17 | 17.71 ± 6.64 | 36.04 ± 14.30 | 11.46 ± 6.87 | 3.13 ± 3.81 | 21.67 ± 13.33 | 40.04 (5) | < 0.001 |

| 身体赢分 | 3.33 ± 3.54 | 83.54 ± 11.69 | 2.08 ± 3.51 | 8.75 ± 6.76 | 1.88 ± 4.24 | 0.42 ± 1.10 | 257.70 (4) | < 0.001 |

| 身体输分 | 33.33 ± 21.95 | 8.96 ± 7.04 | 30.42 ± 16.02 | 14.79 ± 9.05 | 2.50 ± 4.49 | 10.00 ± 14.29 | 44.24 (5) | < 0.001 |

通过实验1和实验2可以发现, 相比基本的6种情绪(快乐、悲伤、厌恶、恐惧、惊喜、愤怒), 本研究中的运动员赢分和输分后的表情, 传递的情绪并非单一, 而是更加复杂和多样化。那么, 人类的大脑又是如何来感知“赢”和“输”?对于分辨赢分和输分面孔, 面孔表情的低区分性和身体表情的高区分性, 是否有着类似的神经机制, 实验3将通过ERP技术考察该问题。

4 实验3:运动员赢分与输分后面孔表情和身体姿势情绪加工的神经机制

4.1 被试

16名在校大学生(女11名, 年龄范围18~26岁, 平均年龄为20.56岁, SD = 2.39), 被试均为右利手, 视力或矫正视力正常。实验前均被告知了实验目的, 并签署了知情同意书。实验通过单位伦理委员会批准。

4.2 实验材料及程序

高强度情绪图片共80张(40张赢分和40张输分), 男女各半。为了增加每种实验条件下的叠加试次数和减少每张图片的重复次数, 相比实验1和实验2使用的60张图片, 本部分脑电实验增加了20张图片(10张赢分和10张输分)。图片的获取方法与实验1相同。总的来说, 实验共有160张图片:40张赢分面孔、40张输分面孔、40张赢分身体、40张输分身体。由未参与脑电实验的20名被试对这160张图片进行效价和强度的评分(评分程序与实验1相同), 结果发现, 赢分面孔效价为4.57 ± 0.22, 强度为5.28 ± 0.19; 输分面孔效价为3.44 ± 014, 强度为5.08 ± 0.22; 赢分身体效价为7.17 ± 0.14, 强度为6.33 ± 0.19; 输分身体效价为4.23 ± 0.13, 强度为3.84 ± 0.17。所有材料以相同的对比度和亮度呈现在黑色背景上。刺激呈现21寸的CRT显示器上(100 Hz 刷新率)。被试距离屏幕大约90 cm。每张图片的视角是为5.7°× 5.7°。

实验采用E-Prime软件呈现刺激与收集行为反应数据。实验包括两部分:面孔实验(只有面孔刺激)与身体实验(只有身体刺激)。实验流程见图4。首先在屏幕上正中央呈现一个注视点500 ms, 间隔400 ms到600 ms的空屏后, 呈现目标刺激(面孔图片或身体图片) 800 ms。然后再呈现空屏2000 ms, 被试做完反应后空屏消失。当空屏出现时, 被试需要对目标刺激的情绪效价作出判断, 是积极还是消极; 如果是积极, 左手食指按“F”键, 如果是消极, 右手食指请按“J”键。按键反应在被试间进行了平衡, 另一半被试作出相反按键。在下个trial出现之前, 还有500 ms的间隔空屏。

图4

面孔图片实验或身体图片实验, 每部分均包括6个组块(block), 每个组块40个试次。每个组块中, 含有两种条件:赢分、输分, 概率相同且随机出现。在整个实验中, 每张图片重复呈现3次, 即每种条件下(赢分或输分)120个试次。面孔与身体实验的顺序在被试间平衡。

4.3 数据采集及分析

使用美国NeuroScan脑电设备公司生产的64导脑电记录与分析系统(NeuroScan 4.5)。电极帽按国际10-20系统扩展的64导电极排布, 以左侧乳突作为参考电极。双眼外侧安置电极记录水平眼电(HEOG), 左眼上下安置电极记录垂直眼电(VEOG)。每个电极处的头皮电阻保持在5 kΩ以下。采样频率为1000 Hz/导。完成连续记录EEG后离线(off line)处理数据。水平和垂直眼电利用 Neuroscan 软件(Scan 4.5)内置的回归程序去除。数字滤波为0.1~30 Hz, 并转为全脑平均参考, 以± 50 μV为标准充分排除其他伪迹。

为研究情绪图片刺激(面孔情绪图片或身体情绪图片)诱发的脑电成分, ERP分析锁时于情绪图片刺激呈现(Onset)的时间点, 分析时程为刺激呈现前100 ms到刺激呈现后800 ms, 刺激呈现前100 ms至0 ms为基线。本实验主要分析P1、N170、EPN和LPP成分, 采用平均波幅的方法。电极点PO7和PO8被用来分析P1 (90~110 ms)、N170 (150~170 ms)和EPN成分(230~260 ms); 电极点P3, Pz, P4用来分析LPP成分(300~550 ms)。

4.4 统计分析方法

描述性统计量表示为均值±标准误。在行为数据的结果统计中, 主要分析反应类型(积极或消极)的比率和反应时。每种实验条件下, 反应类型所占比率的计算方式为:反应次数/总次数, 如面孔赢分条件下, 一共120个试次, 80次判断为“积极”, 40次判断为“消极”。那么积极反应的比率为:80/120 = 0.67, 消极反应的比率为40/120 = 0.33。被试未做按键反应的次数不纳入统计分析。统计方法采用三因素重复测量方差分析, 刺激类型(面孔、身体)×情绪类型(赢分、输分) ×反应类型(积极、消极)。在脑电数据的统计分析中, 对P1、N170、EPN和LPP的平均波幅进行三因素重复测量的方差分析, 刺激类型(面孔、身体)×情绪类型(赢分、输分)×电极。方差分析的P值采用Greenhouse Geisser法校正, 多重比较选择Bonferroni方法。脑电地形图由64导数据得出(见图5)。

图5

4.5 结果

4.5.1 行为结果

每种条件下被评价为积极情绪和消极情绪的比率见图4。反应类型的主效应显著[F(1,15) = 7.36, p =0.016, ηp2 = 0.33], 图片被评为消极情绪的比率(0.44 ± 0.02)大于被评为积极情绪的比率(0.53 ± 0.02)。刺激类型和反应类型的交互作用显著[F(1,15) = 53.77, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.78], 当刺激为面孔时, 图片被评为消极情绪的比率(0.61 ± 0.03)大于被评为积极情绪的比率(0.36 ± 0.03, p < 0.001), 相反地, 当刺激为身体时, 图片被评为积极情绪的比率(0.52 ± 0.02)大于被评为消极情绪的比率(0.45 ± 0.01, p < 0.01)。情绪类型和反应类型的交互作用显著[F(1,15) = 472.30, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.97], 当刺激为赢分图片时, 被评为积极情绪的比率(0.72 ± 0.03)大于被评为消极情绪的比率(0.26 ± 0.02, p < 0.001), 当刺激为输分图片时, 图片被评为消极情绪的比率(0.81 ± 0.02)大于被评为积极情绪的比率(0.17 ± 0.02, p < 0.001)。更为重要的是, 刺激类型、情绪类型和反应类型的三重交互作用显著[F(1,15) = 244.59, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.94], 简单效应分析发现, 在面孔赢分条件下, 积极情绪的比率(0.52 ± 0.04)与消极情绪的比率(0.46 ± 0.04, p =0.42)之间差异不显著, 其它三类条件下, 两种反应比率均存在显著差异, ps < 0.001。面孔输分条件下, 消极情绪的比率(0.77 ± 0.02)大于积极情绪的比率(0.20 ± 0.02); 身体赢分条件下, 积极情绪的比率(0.91 ± 0.02)大于消极情绪的比率(0.06 ± 0.01); 相反地, 身体输分条件下, 消极情绪的比率(0.85 ± 0.02)大于积极情绪的比率(0.13 ± 0.02)。刺激类型主效应、情绪类型主效应、刺激类型和情绪类型的交互作用均不显著(ps >0.2)。

在反应时结果上(见图4), 刺激类型、情绪类型与反应类型的主效应均不显著(ps > 0.05)。刺激类型和反应类型的交互作用显著[F(1,15) = 14.81, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.50], 当刺激为面孔图片时, 被评为积极情绪的反应时(621.1 ± 50. 9 ms)与消极情绪的反应时没有显著性差异(608.3 ± 54.6 ms, p = 0.50), 相反地, 当刺激为身体图片时, 被评为积极情绪的反应时(601.2 ± 44.5 ms)快于被评为消极情绪的反应时(666.7 ± 49.2 ms, p < 0.01)。情绪类型和反应类型的交互作用显著(F(1,15) = 23.91, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.61), 当刺激为赢分图片时, 被评为积极情绪的反应时(541.6 ± 35.6 ms)快于被评为消极情绪的比率(705.1 ± 59.4 ms, p < 0.001), 当刺激为输分图片时, 被评为消极情绪的反应时(680.7 ± 55.5 ms)大于被评为积极情绪的比率(569.9 ± 41.7 ms, p < 0.005)。更为重要的是, 三重交互作用显著[F(1,15) = 14.19, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.49], 简单效应分析发现, 当反应类型与图片的情绪类型的效价一致时, 反应时较短。具体表现在, 面孔赢分条件下, 评价为积极情绪的反应时(582.1 ± 43.9 ms)快于消极情绪的反应时(650.6 ± 60.7 ms, p < 0.05); 面孔输分条件下, 评价为消极情绪的反应时(566.0 ± 50.2 ms)快于积极情绪的反应时(660.2 ± 59.5 ms, p < 0.005); 身体赢分条件下, 评价为积极情绪的反应时(501.2 ± 37.0 ms)快于消极情绪的反应时(759.6 ± 63.2 ms, p < 0.001); 身体输分条件下, 评价为消极情绪的反应时(573.8 ± 41. 8 ms)快于积极情绪的反应时(701.1 ± 58.1 ms, p < 0.005)。

为了评估被试辨别图片情绪的能力, 辨别力指数d ° (Macmillan & Creelman, 2004)在本研究中被使用。d°的计算是基于在赢分图片被判断为积极情绪(击中率)与输分图片被判断为积极情绪(虚报率)。单样本t检验结果发现, 面孔条件下, 平均d° (M = 0.65, SD = 0.24)及身体条件下平均d° (M = 1.89, SD = 0.38)与0差异均极其显著[面孔:t (15) = 10.77, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 2.71; 身体:t (15) = 19.91, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 4.97]。结果表明, 被试对图片情绪的辨别能力, 无论面孔还是身体条件下, 均处在概率水平以上。

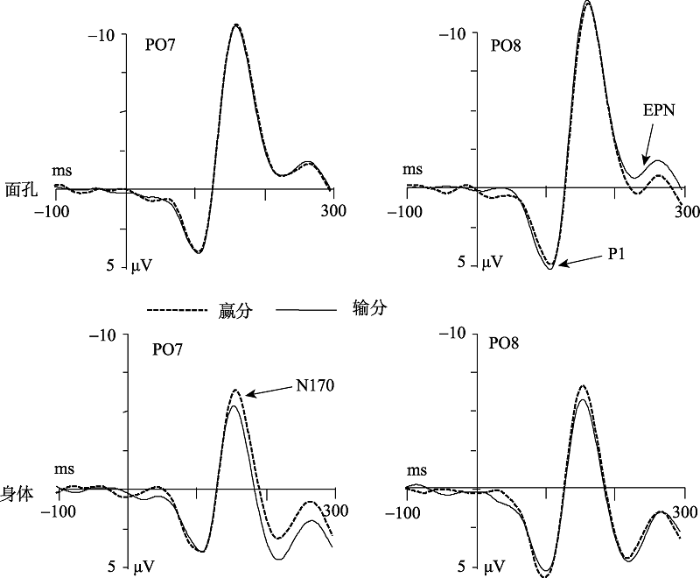

4.5.2 ERP 结果

对身体及面孔刺激诱发脑电成分(P1、N170、EPN和LPP)的平均波幅进行三因素重复测量的方差分析, 刺激类型(面孔vs身体)×情绪类型(赢vs输)×电极, 结果发现:

P1

电极的主效应显著[F(1,15) = 6.84, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.31], 右侧PO8电极点的波幅值(4.77 ± 0.92 μV)大于左侧PO7电极点的波幅值(3.55 ± 0.84 μV)。刺激类型与情绪类型的主效应及变量间的交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。

N170

刺激类型的主效应显著[F(1,15) = 36.12, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.71], 面孔(-10.54 ± 1.42 μV) 比身体(-5.62 ± 1.22 μV)诱发更负的N170波幅。刺激类型与情绪类型的交互作用显著[F(1,15) = 6.66, p = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.31]。简单效应的分析发现(见图6), 赢分身体(-6.09 ± 1.30 μV)比输分身体(-5.15 ± 1.15 μV)

诱发更负的N170波幅(p < 0.005), 而赢分(-10.48 ± 1.40 μV)与输分面孔(-10.59 ± 1.45 μV)之间无显著差异(p = 0.136)。电极的主效应、刺激类型和电极的交互作用、情绪类型和电极的交互作用以及刺激类型、情绪类型和电极的三重交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。

图6

EPN

刺激类型的主效应显著[F(1,15) = 64.81; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.812], 面孔(-0.88 ± 1.30 μV) 比身体(2.69 ± 1.25 μV)诱发更负的EPN波幅。情绪类型与电极的交互作用显著[F(1,15) = 32.45; p < 0.001; ηp2 = 0.68]。简单效应分析发现, 在P07电极点上, 赢分(0.34 ± 1.28 μV)比输分(0.92 ± 1.26 μV)诱发更负的波幅, 而在PO8电极点上, 赢分(1.33 ± 1.44 μV)与输分(1.02 ± 1.41 μV)诱发的波幅没有显著差异。刺激类型与情绪类型的交互作用显著, F(1,15) = 9.49, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.39。简单效应分析发现(见图6), 输分面孔(-1.17 ± 1.28 μV)比赢分面孔(-0.60 ± 1.34 μV)诱发更负的EPN波幅(p < 0.05), 相反, 赢分身体(-2.27 ± 1.23 μV)比输分身体(-3.11 ± 1.28 μV)诱发更负的EPN波幅(p < 0.01)。情绪类型的主效应、电极的主效应、刺激类型和电极的交互作用以及刺激类型、情绪类型和电极的三重交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。

LPP

刺激类型的主效应显著[F(1,15) = 13.38, p < 0.005, ηp2 = 0.47], 身体(5.73 ± 0.67 μV) 比面孔(4.60 ± 0.60 μV)诱发更大的LPP成分。情绪类型的主效应显著 [F(1,15) = 22.97, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.61], 赢分图片(5.41 ± 0.63 μV)比输分图片(4.92 ± 0.61 μV)诱发更大的LPP成分(见图7)。电极的主效应显著[F(2,30) = 4.07, p < 0.05, ηp2= 0.21], 电极点Pz (6.02 ±0.62 μV)比电极点P3 (4.60 ± 0.67 μV, p < 0.01))和P4 (4.88 ± 0.77 μV, p < 0.01)诱发更大的LPP成分。所有二重和三重交互作用均不显著(ps > 0.05)。

图7

4.6 讨论

实验3从行为和脑电上验证了面孔表情和身体姿势情绪识别的不同。从行为结果看, 身体比面孔能够被更明确地区分正负性情绪, 这与Aviezer等人(2012)的观点是相同的, 身体比面孔能提供更有效的情绪信息。同时, 我们发现, 面孔对情绪信息并非完全无诊断性, 对面孔情绪的判断处于概率水平以上, 如输分面孔更多地被评价为消极情绪。但是, 赢分面孔被评价为积极情绪和消极情绪的概率无显著差异。

在ERP结果上, 面孔表情和身体姿势这两类不同的情绪载体诱发的脑电波形存在不同。首先, 与已有的研究一致(Bentin et al., 1996; Righart & de Gelder, 2007), 相比身体图片, 面孔图片诱发了更大的N170波幅, N170成分可能更加敏感于面孔的结构编码加工。其次, 面孔比身体诱发了更负的EPN成分。EPN反映了知觉编码完成后, 视觉皮层对情绪信息给予进一步的选择性注意(Schupp, Flaisch, Stockburger, & Junghöfer, 2006)。本文结果显示, 在N170知觉编码阶段, 大脑完成了对赢分身体和输分身体的区分, 可能在此后EPN阶段, 大脑给予身体图片的加工分配了较面孔加工更少的注意资源, 导致身体图片对应的EPN波幅较小。在较晚期的加工阶段, 身体比面孔诱发了更大的LPP成分。一般来说, LPP成分与刺激的评估与分类有关(Kutas, McCarthy, & Donchin, 1977; Pritchard, 1981), 同时, 与投入的心理资源也存在一定的关系(Kok, 1997)。本文结果显示, 大脑对携带有更明确情绪的身体图片进行了更深入的加工, 进一步评估与效价有关的更细致的信息, 并将不同情绪种类的图片区分开。

除了面孔和身体诱发ERP波形不同之外, 本文更关心的是面孔表情和身体姿势影响赢分情绪和输分情绪加工机制的不同。本文发现, 面孔图片上, 输分面孔比赢分面孔诱发了更负的EPN波幅。对于身体图片, 同样发现了输分和赢分图片的差异, 表现在多个ERP成分上, 如N170、EPN和LPP。ERP结果为行为结果提供了解释, 行为学所发现的身体的正负性情绪能够更明确地被区分开来, 这可能来源于大脑对赢分身体和输分身体多阶段有区别的加工。我们将在总讨论部分对此深入讨论。

5 总讨论

本文研究了面孔和身体在运动员赢分和输分两种情绪条件下的加工。实验1和实验3的行为结果发现, 中国运动员的表情存在面孔表情效价的低区分性和身体表情效价的高区分性, 相比面孔条件, 身体条件下赢分与输分图片之间的效价差异较大, 身体赢分图片被评价为积极情绪, 身体输分图片被评价为消极情绪。实验2的结果发现, 面孔表情比身体姿势传递的情绪更加复杂和多样化。同时, 在脑电上, 身体条件下, 在多个ERP成分上存在赢分与输分图片的差别。

5.1 面孔表情的情绪多样性和身体姿势的情绪单一性

三个实验的行为数据表明, 身体比面孔能够更加明确地被判断出效价的正负性, 可能源于面孔表情传递的情绪多样性和身体姿势传递的情绪较为单一性。实验2结果发现, 运动员的面孔可能传递着更多样化的情绪, 如赢分面孔较高频率被感知的情绪有快乐、愤怒、悲伤, 输分面孔较高频率被感知的情绪有悲伤、厌恶、快乐。相对而言, 身体表达的情绪较为单一, 尤其是赢分身体, 最显著的情绪为高兴, 输分身体偏向悲伤和中性情绪。

相比输分情景下的面孔, 赢分面孔所传递的情绪更加复杂, 甚至存在与图片所处的情景效价相反的情绪, 如实验2中, 赢分面孔下, 消极情绪的概率为55% (悲伤、愤怒、恐惧和厌恶四种比率的总和), 积极情绪的概率为33%。也就是说, 赢分后存在多种类型的情绪反应, 既有正性情绪, 又有负性情绪。本文作者参考了2016年里约奥运会男单羽毛球决赛和女单乒乓球决赛时录像, 发现运动员(谌龙、丁宁)在赛点赢分后的即刻情绪反应, 是与情景比较一致的, 例如会高举双手, 朝天呐喊, 挥舞手臂, 表达一种愉悦的胜利情绪, 然而几秒之后, 运动员则激动流泪, 甚至跪地痛哭。赢分后情绪反应的多样性导致了面孔效价的划分变得困难, 这与实验3中赢分面孔被评价为积极情绪和消极情绪的比率无显著差异是一致的。实验1中, 赢分面孔的效价均值为5.57分, 相比5分为中性情绪, 赢分面孔不具有非常明确的正负性效价信息。然而, Aviezer等人(2012)以及 Wang,Xia和Zhang (2017)研究表明, 当呈现一张完整的赢分图片(包含面孔和身体信息)时, 赢分图片的效价为7分左右, 表明在身体信息辅助的情况下, 赢分面孔更偏向于判断为积极情绪。

在对运动员赢分或输分的情绪判断中, 身体姿势比面孔表情存在一定的优势。研究表明, 人类情绪效价的判断与趋近和回避动机系统有关, 如正性情绪引起趋近反应, 负性情绪引起回避反应, 而趋近和回避行为可以反映在身体姿势中(Xiao, Li, Li, & Wang, 2016)。趋近动机可以从伸展、张开或向前身体动作中推测出来(本研究中的赢分身体), 而回避动机可以从弯曲、闭合、向下或向后的身体动作中推测出来(本研究中的输分身体)。在情绪感知中, 人们会整合来自多通道的情绪信息, 如面孔、身体、声音(Bogart, Tickle-Degnen, & Ambady, 2014)。至于哪个通道的信息在情绪感知上更具有优势, 可能取决于各通道信息的清晰程度。在本研究中, 赢分或输分情绪对于运动员来说, 情绪体验比较强烈, 面孔传递的情绪不够明确, 身体姿势传递的情绪相对清晰, 因此身体姿势在情绪表达上可能发挥着更大的作用。

总的来说, 从情绪识别的角度看, 1)对于评估运动员所处的真实情景, 身体姿势比面孔表情似乎更能提供与其情景一致的信息; 2)相比输分面孔, 赢分面孔传递的情绪更加复杂, 不能明确地推测出运动员输赢情况。

5.2 赢分和输分情绪加工的神经机制

(1) 早期P1阶段, 无法识别运动员的情绪信息

在脑电结果上, 本文从情绪加工的三阶段理论(W. Luo et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2014), 分析和解释赢分情绪和输分情绪的脑内时程变化过程。在情绪的第一加工阶段, P1成分反映了情绪信息的自动加工或快速加工(W. Luo et al., 2010), 在基本表情的研究中, 相比中性刺激, 威胁性面孔或身体会诱发更大的P1波幅(Zhang, Wang, & Luo, 2012; 张丹丹等, 2015)。本文结果显示, 无论是面孔还是身体, 均未发现胜利和失败表情在P1成分上的区别, 其原因可能有二。第一, 可能是由于本文实验材料来源于真实的生活, 传递的情绪内容相比基本表情更加复杂和多样化(实验2), 导致大脑无法对该类刺激快速地自动化加工。第二, 也可能是由于输分表情和赢分表情虽然强度很高, 但是对于生存的威胁性程度较低, 而P1成分对威胁性信息更加敏感, 如恐惧面孔、恐惧身体、负性词语。

(2) 中期阶段, 情绪载体的不同影响赢分和输分的识别

情绪加工的第二个阶段表现在N170和EPN成分(W. Luo et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2014; 张丹丹, 罗文波, 罗跃嘉, 2013)。在身体条件下, 胜利比失败表情诱发了更负的N170成分和EPN成分, 而在面孔条件下, 情绪效应仅反映在EPN成分上, 失败比胜利表情诱发了更负的EPN波幅。N170成分, 反映了面孔或身体的结构编码, 一般而言, 面孔比非面孔刺激(如汽车、手、房子)诱发的N170波幅更大(Bentin et al., 1996; Eimer, 2000)。与此一致, 本文实验3的结果发现, 面孔比身体诱发了更大的N170波幅。更为重要的是, 本文发现N170情绪效应出现在身体图片条件下。已有研究发现, 身体姿势包含的动作因素影响N170波幅(Borhani, Borgomaneri, Làdavas, & Bertini, 2016; Borhani, Làdavas, Maier, Avenanti, & Bertini, 2015), 相比动作量少的图片, 包含较多动作的身体刺激会诱发较大波幅。本文中, 胜利的身体姿势呈现出一种展开的姿态, 如高举的手臂或者紧握的拳头, 传递着胜利的喜悦, 而失败的身体姿势动作幅度较小, 如低垂的手臂。因此, 本文结果可能是由于胜利和失败的身体传递的动作不同导致的。相对比而言, 赢分面孔或输分面孔之间无N170情绪效应, 这可能有两个原因, 第一, 正如引言中提到, 有关N170成分对面孔表情的识别是否敏感存在一定的争议, 部分研究发现N170成分不受到面孔表情的影响(Eimer et al., 2008; Kiss & Eimer, 2008)。本文中面孔表情条件下无N170成分的情绪效应, 也可能是由于N170成分不够敏感于面孔表情的探测。第二, 赢分面孔或输分面孔具有情绪的复杂性和多样性, 没有比较明确的区分性的动作, 无法做出有效的情绪分类, 即使N170成分对面孔表情识别具有一定的区分性, 导致赢分面孔和输分面孔诱发的N170波幅也可能不存在显著差异。

EPN反映了对情绪信息的选择性注意(侠牧等, 2014), 情绪性信息会比中性刺激诱发更负的EPN成分(Kissler & Herbert, 2013; Zhang et al., 2014)。在本文结果中, 情绪效应在面孔与身体条件是相反的:在面孔条件下, 失败表情的EPN更负, 在身体条件下, 胜利表情的EPN更负。学者们认为, EPN的情绪效应, 反映了在知觉编码完成后, 视觉皮层对环境中的情绪信息给予进一步的选择性注意(Schupp et al., 2006; 侠牧等, 2014)。本文结果表明, 输分面孔比赢分面孔更能引起大脑的注意, 而赢分身体比输分身体更能引起大脑的注意。也就是说, 情绪的载体影响了不同情绪的加工。

(3) 晚期阶段, 情绪信息的分类与更深入加工

在情绪加工的晚期, 在LPP成分上存在情绪类型的主效应:无论面孔还是身体刺激, 均发现赢分图片比输分图片诱发了更大的LPP波幅。一般来说, LPP成分反映了刺激的深入加工与分类(Kutas et al., 1977; Pritchard, 1981), 也反映了人们投入心理资源的多少(Kok, 1997)。与本文研究结果一致, Olofsson等人对与有关情绪图片的ERP研究进行了综述(Olofsson, Nordin, Sequeira, & Polich, 2008), 发现积极愉悦的刺激比非愉悦刺激会诱发更大LPP成分。本文结果中, 赢分图片诱发的LPP波幅更大, 一方面表明大脑在晚期加工阶段进一步将赢分与输分图片进行更深入加工和分类, 另一方面表明大脑给予“赢”的情绪更多的注意力, 这可能与人们在日常生活或者体育运动中对 “赢”有更多的期待有关。

5.3 研究不足与展望

本研究也存在某些不足, 需要在未来的研究中加以完善。在实验2, 实验任务设置方面, 要求被试对图片的情绪进行六选一(中性、快乐、悲伤、愤怒、恐惧、厌恶)的判断。但是, 图片传递的情绪有可能含有更多的类型, 例如, 赢分运动员可能产生自豪、兴奋等情绪, 输分运动员可能产生沮丧、懊恼、自责、羞愧、后悔等情绪, 这些情绪可能是一种单一的情绪, 也有可能是一种复合情绪。具体的情绪类型可能受到多种因素的影响, 如运动员的人格特点、所处环境、比赛的重要程度等。在未来的研究中, 可以对运动员本人和观众进行开放式调查, 可能会存在哪些情绪类型, 再进行相关的评价。

总的来说, 本文对远动员赢分和输分后的情绪加工机制进行了探讨, 揭示面孔和身体在传递情绪上存在的不同, 有助于人们深入了解情绪脑的工作机制。同时, 采用生活中的真实情绪刺激, 扩展了人们对情绪识别的认识, 加深了我们对面孔加工复杂性的理解。

6 结论

综上所述, 本文在Aviezer等人的基础上, 采用行为学和ERP技术, 考察了远动员赢分和输分后的情绪类型和加工时程, 回答了论文提出的三个问题。结果表明:

(1)从情绪识别的角度上, 中国运动员的表情存在面孔表情效价的低区分性和身体表情效价的高区分性。对于评估运动员所处的真实情景, 身体姿势比面孔表情似乎更能提供与其情景一致的信息。

(2)“面孔表情效价的低区分性和身体表情效价的高区分性”这一现象的原因, 可能是由于面孔和身体传递情绪内容的复杂程度不同, 面孔含有的情绪更加复杂和多样化, 身体传递的情绪信息更为单一。

(3)在脑内时间进程上, 身体的情绪信息更早地被大脑识别到, 表现在N170成分上。大脑对面孔的情绪识别表现在EPN成分上。在加工的后期, 无论面孔还是身体, 大脑均对赢分表情给予更多的注意。大脑在多个阶段对身体进行情绪评估与分类, 为行为学上身体能够提供更有区分性的效价信息提供了证据。

参考文献

Neural systems for recognizing emotion

DOI:10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00301-X

URL

PMID:12015233

[本文引用: 2]

Abstract Recognition of emotion draws on a distributed set of structures that include the occipitotemporal neocortex, amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex and right frontoparietal cortices. Recognition of fear may draw especially on the amygdala and the detection of disgust may rely on the insula and basal ganglia. Two important mechanisms for recognition of emotions are the construction of a simulation of the observed emotion in the perceiver, and the modulation of sensory cortices via top-down influences.

Thrill of victory or agony of defeat? Perceivers fail to utilize information in facial movements

DOI:10.1037/emo0000073

URL

PMID:26010575

Abstract Although the distinction between positive and negative facial expressions is assumed to be clear and robust, recent research with intense real-life faces has shown that viewers are unable to reliably differentiate the valence of such expressions (Aviezer, Trope, & Todorov, 2012). Yet, the fact that viewers fail to distinguish these expressions does not in itself testify that the faces are physically identical. In Experiment 1, the muscular activity of victorious and defeated faces was analyzed. Higher numbers of individually coded facial actions-particularly smiling and mouth opening-were more common among winners than losers, indicating an objective difference in facial activity. In Experiment 2, we asked whether supplying participants with valid or invalid information about objective facial activity and valence would alter their ratings. Notwithstanding these manipulations, valence ratings were virtually identical in all groups, and participants failed to differentiate between positive and negative faces. While objective differences between intense positive and negative faces are detectable, human viewers do not utilize these differences in determining valence. These results suggest a surprising dissociation between information present in expressions and information used by perceivers. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2015 APA, all rights reserved).

Body cues, not facial expressions, discriminate between intense positive and negative emotions

DOI:10.1126/science.1224313

URL

PMID:23197536

[本文引用: 6]

The distinction between positive and negative emotions is fundamental in emotion models. Intriguingly, neurobiological work suggests shared mechanisms across positive and negative emotions. We tested whether similar overlap occurs in real-life facial expressions. During peak intensities of emotion, positive and negative situations were successfully discriminated from isolated bodies but not faces. Nevertheless, viewers perceived illusory positivity or negativity in the nondiagnostic faces when seen with bodies. To reveal the underlying mechanisms, we created compounds of intense negative faces combined with positive bodies, and vice versa. Perceived affect and mimicry of the faces shifted systematically as a function of their contextual body emotion. These findings challenge standard models of emotion expression and highlight the role of the body in expressing and perceiving emotions.

Electrophysiological studies of face perception in humans

DOI:10.1162/jocn.1996.8.6.551

URL

PMID:2927138

[本文引用: 3]

Event-related potentials () associated with face perception were recorded with scalp electrodes from normal volunteers. Subjects performed a visual target detection task in which they mentally counted the number of occurrences of pictorial stimuli from a designated category such us . In separate experiments, target stimuli were embedded within a series of other stimuli including unfamiliar faces and isolated face components, inverted faces, distorted faces, animal faces, and other nonface stimuli. Unman faces evoked a negative potential at 172 msec (N170), which was absent from the elicited by other animate and inanimate nonface stimuli. N170 was largest over the posterior temporal scalp and was larger over the right than the left hemisphere. N170 was delayed when faces were presented upside-down, but its amplitude did not change. When presented in isolation, eyes elicited an N170 that was significantly larger than that elicited by whole faces, while noses and lips elicited small negative about 50 msec later than N170. Distorted faces, in which the locations of inner face components were altered, elicited an N170 similar in amplitude to that elicited by normal faces. However, faces of , hands, cars, and items of furniture did not evoke N170. N170 may reflect the operation of a neural mechanism tuned to detect (as opposed to identify) faces, similar to the "structural encoder" suggested by Bruce and Young (1986). A similar function has been proposed for the face-selective N200 recorded from the middle fusiform and posterior inferior temporal gyri using subdural electrodes in (Allison, McCarthy, Nobre, Puce, & Belger, 1994c). However, the differential sensitivity of N170 to eyes in isolation suggests that N170 may reflect the activation of an eye-sensitive region of cortex. The voltage distribution of N170 over the scalp is consistent with a neural generator located in the occipitotemporal sulcus lateral to the fusiform/inferior temporal region that generates N200.

The face-specific N170 component is modulated by emotional facial expression

DOI:10.1186/1744-9081-3-7

URL

PMID:1794418

[本文引用: 1]

Background According to the traditional two-stage model of face processing, the face-specific N170 event-related potential (ERP) is linked to structural encoding of face stimuli, whereas later ERP components are thought to reflect processing of facial affect. This view has recently been challenged by reports of N170 modulations by emotional facial expression. This study examines the time-course and topography of the influence of emotional expression on the N170 response to faces. Methods Dense-array ERPs were recorded in response to a set (n = 16) of fear and neutral faces. Stimuli were normalized on dimensions of shape, size and luminance contrast distribution. To minimize task effects related to facial or emotional processing, facial stimuli were irrelevant to a primary task of learning associative pairings between a subsequently presented visual character and a spoken word. Results N170 to faces showed a strong modulation by emotional facial expression. A split half analysis demonstrates that this effect was significant both early and late in the experiment and was therefore not associated with only the initial exposures of these stimuli, demonstrating a form of robustness against habituation. The effect of emotional modulation of the N170 to faces did not show significant interaction with the gender of the face stimulus, or hemisphere of recording sites. Subtracting the fear versus neutral topography provided a topography that itself was highly similar to the face N170. Conclusion The face N170 response can be influenced by emotional expressions contained within facial stimuli. The topography of this effect is consistent with the notion that fear stimuli exaggerates the N170 response itself. This finding stands in contrast to previous models suggesting that N170 processes linked to structural analysis of faces precede analysis of emotional expression, and instead may reflect early top-down modulation from neural systems involved in rapid emotional processing.

Communicating without the face: Holistic perception of emotions of people with facial paralysis

DOI:10.1080/01973533.2014.917973

URL

PMID:26412919

[本文引用: 1]

People with facial paralysis (FP) report social difficulties, but some attempt to compensate by increasing expressivity in their bodies and voices. We examined perceivers' emotion judgments of videos of people with FP to understand how they interpret the combination of an inexpressive face with an expressive body and voice. Results suggest that perceivers form less favorable impressions of people with severe FP, but compensatory expression is effective in improving impressions. Perceivers seemed to form holistic impressions when rating happiness and possibly sadness. Findings have implications for basic emotion research and social functioning interventions for people with FP.

The effect of alexithymia on early visual processing of emotional body postures

DOI:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.12.010

URL

PMID:26762700

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Body postures convey emotion and motion-related information useful in social interactions. Early visual encoding of body postures, reflected by the N190 component, is modulated both by motion (i.e., postures implying motion elicit greater N190 amplitudes than static postures) and by emotion-related content (i.e., fearful postures elicit the largest N190 amplitude). At a later stage, there is a fear-related increase in attention, reflected by an early posterior negativity (EPN) (Borhani et al., 2015). Here, we tested whether difficulties in emotional processing (i.e., alexithymia) affect early and late visual processing of body postures. Low alexithymic participants showed emotional modulation of the N190, with fearful postures specifically enhancing N190 amplitude. In contrast, high alexithymic participants showed no emotional modulation of the N190. Both groups showed preserved encoding of the motion content. At a later stage, a fear-related modulation of the EPN was found for both groups, suggesting that selective attention to salient stimuli is the same in both low and high alexithymia.

Emotional and movement-related body postures modulate visual processing

DOI:10.1093/scan/nsu167

URL

PMID:25556213

[本文引用: 1]

Human body postures convey useful information for understanding others鈥 emotions and intentions. To investigate at which stage of visual processing emotional and movement-related information conveyed by bodies is discriminated, we examined event-related potentials elicited by laterally presented images of bodies with static postures and implied-motion body images with neutral, fearful or happy expressions. At the early stage of visual structural encoding (N190), we found a difference in the sensitivity of the two hemispheres to observed body postures. Specifically, the right hemisphere showed a N190 modulation both for the motion content (i.e. all the observed postures implying body movements elicited greater N190 amplitudes compared with static postures) and for the emotional content (i.e. fearful postures elicited the largest N190 amplitude), while the left hemisphere showed a modulation only for the motion content. In contrast, at a later stage of perceptual representation, reflecting selective attention to salient stimuli, an increased early posterior negativity was observed for fearful stimuli in both hemispheres, suggesting an enhanced processing of motivationally relevant stimuli. The observed modulations, both at the early stage of structural encoding and at the later processing stage, suggest the existence of a specialized perceptual mechanism tuned to emotion- and action-related information conveyed by human body postures.

Do facial expressions signal specific emotions? Judging emotion from the face in context

DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.205

URL

PMID:8636880

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Certain facial expressions have been theorized to be easily recognizable signals of specific emotions. If so, these expressions should override situationally based expectations used by a person in attributing an emotion to another. An alternative account is offered in which the face provides information relevant to emotion but does not signal a specific emotion. Therefore, in specified circumstances, situational rather than facial information was predicted to determine the judged emotion. This prediction was supported in 3 studies--indeed, in each of the 22 cases examined (e.g., a person in a frightening situation but displaying a reported "facial expression of anger" was judged as afraid). Situational information was especially influential when it suggested a nonbasic emotion (e.g., a person in a painful situation but displaying a "facial expression of fear" was judged as in pain).

The many faces of the emotional body. In J. Decety & Y. Christen (Eds.), New frontiers in social neuroscience (Vol

Towards the neurobiology of emotional body language

DOI:10.1038/nrn1872

URL

PMID:16495945

[本文引用: 2]

Abstract People's faces show fear in many different circumstances. However, when people are terrified, as well as showing emotion, they run for cover. When we see a bodily expression of emotion, we immediately know what specific action is associated with a particular emotion, leaving little need for interpretation of the signal, as is the case for facial expressions. Research on emotional body language is rapidly emerging as a new field in cognitive and affective neuroscience. This article reviews how whole-body signals are automatically perceived and understood, and their role in emotional communication and decision-making.

The face-specific N170 component reflects late stages in the structural encoding of faces

DOI:10.1097/00001756-200007140-00050

URL

PMID:10923693

[本文引用: 1]

To investigate which stages in the structural encoding of faces are reflected by the face-specific N170 component, (event-related brain potentials) were recorded in response to different types of face and non-face stimuli. The N170 was strongly attenuated for cheek and back views of faces relative to front and profile views, demonstrating that it is not merely triggered by head detection. Attenuated and delayed N170 components were elicited for faces lacking internal features as well as for faces without external features, suggesting that it is not exclusively sensitive to salient internal features. It is suggested that the N170 is linked to late stages of structural encoding, where representations of global face configurations are generated in order to be utilised by subsequent face recognition processes.

Links between rapid ERP responses to fearful faces and conscious awareness

DOI:10.1348/174866407X245411

URL

PMID:19330049

[本文引用: 2]

Abstract To study links between rapid ERP responses to fearful faces and conscious awareness, a backward-masking paradigm was employed where fearful or neutral target faces were presented for different durations and were followed by a neutral face mask. Participants had to report target face expression on each trial. When masked faces were clearly visible (200 ms duration), an early frontal positivity, a later more broadly distributed positivity, and a temporo-occipital negativity were elicited by fearful relative to neutral faces, confirming findings from previous studies with unmasked faces. These emotion-specific effects were also triggered when masked faces were presented for only 17 ms, but only on trials where fearful faces were successfully detected. When masked faces were shown for 50 ms, a smaller but reliable frontal positivity was also elicited by undetected fearful faces. These results demonstrate that early ERP responses to fearful faces are linked to observers' subjective conscious awareness of such faces, as reflected by their perceptual reports. They suggest that frontal brain regions involved in the construction of conscious representations of facial expression are activated at very short latencies.

The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding

Do bodily expressions compete with facial expressions? Time course of integration of emotional signals from the face and the body

N170 response to facial expressions is modulated by the affective congruency between the emotional expression and preceding affective picture

ERPs reveal subliminal processing of fearful faces

Emotion, etmnooi, or emitoon?--Faster lexical access to emotional than to neutral words during reading

Event-related-potential (ERP) reflections of mental resource̊s: A review and synthesis

Augmenting mental chronometry: The P300 as a measure of stimulus evaluation time

An ERP study of emotional face processing in the adult and infant brain

DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00994.x

URL

PMID:2976653

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract To examine the ontogeny of emotional face processing, event-related potentials (ERPs) were recorded from adults and 7-month-old infants while viewing pictures of fearful, happy, and neutral faces. Face-sensitive ERPs at occipital emporal scalp regions differentiated between fearful and neutral/happy faces in both adults (N170 was larger for fear) and infants (P400 was larger for fear). Behavioral measures showed no overt attentional bias toward fearful faces in adults, but in infants, the duration of the first fixation was longer for fearful than happy faces. Together, these results suggest that the neural systems underlying the differential processing of fearful and happy/neutral faces are functional early in life, and that affective factors may play an important role in modulating infants' face processing.

Neural dynamics for facial threat processing as revealed by gamma band synchronization using MEG

Emotional automaticity is a matter of timing

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.BC-5668-09.2010

URL

PMID:3842481

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract There has been a long controversy concerning whether the amygdala's response to emotional stimuli is automatic or dependent on attentional load. Using magnoencephalography and an advanced beamformer source localization technique, we found that amygdala automaticity was a function of time: while early amygdala responding to emotional stimuli (40-140 ms) was unaffected by attentional load, later amygdala response (280-410 ms), subsequent to frontoparietal cortex activity, was modulated by attentional load.

Three stages of facial expression processing: ERP study with rapid serial visual presentation

DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.018

URL

PMID:19770052

[本文引用: 4]

Electrophysiological correlates of the processing facial expressions were investigated in subjects performing the rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) task. The peak latencies of the event-related potential (ERP) components P1, vertex positive potential (VPP), and N170 were 165, 240, and 240ms, respectively. The early anterior N100 and posterior P1 amplitudes elicited by fearful faces were larger than those elicited by happy or neutral faces, a finding which is consistent with the presence of a egativity bias.The amplitude of the anterior VPP was larger when subjects were processing fearful and happy faces than when they were processing neutral faces; it was similar in response to fearful and happy faces. The late N300 and P300 not only distinguished emotional faces from neutral faces but also differentiated between fearful and happy expressions in lag2. The amplitudes of the N100, VPP, N170, N300, and P300 components and the latency of the P1 component were modulated by attentional resources. Deficient attentional resources resulted in decreased amplitude and increased latency of ERP components. In light of these results, we present a hypothetical model involving three stages of facial expression processing.

The thrill of victory and the agony of defeat: Spontaneous expressions of medal winners of the 2004 Athens Olympic Games

Rapid perceptual integration of facial expression and emotional body language

An approach to environmental psychology. Cambridge, MA:

Towards a cognitive theory of emotions

DOI:10.1080/02699938708408362

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract A theory is proposed that emotions are cognitively based states which co-ordinate quasi-autonomous processes in the nervous system. Emotions provide a biological solution to certain problems of transition between plans, in systems with multiple goals. Their function is to accomplish and maintain these transitions, and to communicate them to ourselves and others. Transitions occur at significant junctures of plans when the evaluation of success in a plan changes. Complex emotions are derived from a small number of basic emotions and arise at junctures of social plans.

Affective picture processing: An integrative review of ERP findings

DOI:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.11.006

URL

PMID:18164800

[本文引用: 1]

The review summarizes and integrates findings from 40 years of event-related potential (ERP) studies using pictures that differ in valence (unpleasant-to-pleasant) and arousal (low-to-high) and that are used to elicit emotional processing. Affective stimulus factors primarily modulate ERP component amplitude, with little change in peak latency observed. Arousal effects are consistently obtained, and generally occur at longer latencies. Valence effects are inconsistently reported at several latency ranges, including very early components. Some affective ERP modulations vary with recording methodology, stimulus factors, as well as task-relevance and emotional state. Affective ERPs have been linked theoretically to attention orientation for unpleasant pictures at earlier components (300 ms). Theoretical issues, stimulus factors, task demands, and individual differences are discussed.

Electrophysiological evidence for early non-conscious processing of fearful facial expressions

DOI:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.08.007

URL

PMID:18804496

[本文引用: 1]

Non-conscious processing of emotionally expressive faces has been found in patients with damage to visual brain areas and has been demonstrated experimentally in healthy controls using visual masking procedures. The time at which this subliminal processing occurs is not known.To address this question, a group of healthy participants performed a fearful face detection task in which backward masked fearful and non-fearful faces were presented at durations ranging from 16 to 266 ms. On the basis of the group's behavioural results, high-density event-related potentials were analysed for subliminal, intermediate and supraliminal presentations. Subliminally presented fearful faces were found to produce a stronger posterior negativity at 170 ms (N170) than non-fearful faces. This increase was also observed for intermediate and supraliminal conditions. A later component, the N2 occurring between 260 and 300 ms, was the earliest component related to stimulus detectability, increasing with target duration and differentiating fearful from non-fearful faces at longer durations of presentation. Source localisation performed on the N170 component showed that fear produced a greater activation of extrastriate visual areas, particularly on the right.Whether they are presented subliminally or supraliminally, fearful faces are processed at an early stage in the stream of visual processing, giving rise to enhanced activation of right extrastriate temporal cortex as early as 170 ms post-stimulus onset.

Early ERP modulation for task-irrelevant subliminal faces

DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00088

URL

PMID:3110345

[本文引用: 1]

A number of investigations have reported that emotional faces can be processed subliminally, and that they give rise to specific patterns of brain activation in the absence of awareness. Recent event-related potential (ERP) studies have suggested that electrophysiological differences occur early in time (<20065ms) in response to backward-masked emotional faces. These findings have been taken as evidence of a rapid non-conscious pathway, which would allow threatening stimuli to be processed rapidly and subsequently allow appropriate avoidance action to be taken. However, for this to be the case, subliminal processing should arise even if the threatening stimulus is not attended. This point has in fact not yet been clearly established. In this ERP study, we investigated whether subliminal processing of fearful faces occurs outside the focus of attention. Fourteen healthy participants performed a line judgment task while fearful and non-fearful (happy or neutral) faces were presented both subliminally and supraliminally. ERPs were compared across the four experimental conditions (i.e., subliminal and supraliminal; fearful and non-fearful). The earliest differences between fearful and non-fearful faces appeared as an enhanced posterior negativity for the former at 17065ms (the N170 component) over right temporo-occipital electrodes. This difference was observed for both subliminal (p<650.05) and supraliminal presentations (p<650.01). Our results confirm that subliminal processing of fearful faces occurs early in the course of visual processing, and more importantly, that this arises even when the subject's attention is engaged in an incidental task.

Electrophysiological correlates of rapid spatial orienting towards fearful faces

DOI:10.1093/cercor/bhh023

URL

PMID:15054077

[本文引用: 1]

We investigated the spatio-temporal dynamic of attentional bias towards fearful faces. Twelve participants performed a covert spatial orienting task while recording visual event-related brain potentials (VEPs). Each trial consisted of a pair of faces (one emotional and one neutral) briefly presented in the upper visual field, followed by a unilateral bar presented at the location of one of the faces. Participants had to judge the orientation of the bar. Comparing VEPs to bars shown at the location of an emotional (valid) versus neutral (invalid) face revealed an early effect of spatial validity: the lateral occipital P1 component (similar to130 ms post-stimulus) was selectively increased when a bar replaced a fearful face compared to when the same bar replaced a neutral face. This effect was not found with upright happy faces or inverted fearful faces. A similar amplification of P1 has previously been observed in electrophysiological studies of spatial attention using non-emotional cues. In a behavioural control experiment, participants were also better at discriminating the orientation of the bar when it replaced a fearful rather than a neutral face. In addition, VEPs time-locked to the face-pair onset revealed a C1 component (similar to90 ms) that was greater for fearful than happy faces. Source localization (LORETA) confirmed an extrastriate origin of the P1 response showing a spatial validity effect, and a striate origin of the C1 response showing an emotional valence effect. These data suggest that activity in primary visual cortex might be enhanced by fear cues as early as 90 ms post-stimulus, and that such effects might result in a subsequent facilitation of sensory processing for a stimulus appearing at the same location. These results provide evidence for neural mechanisms allowing rapid, exogenous spatial orienting of attention towards fear stimuli.

Impaired face and body perception in developmental prosopagnosia

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0707753104

URL

PMID:17942679

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Prosopagnosia is a deficit in face recognition in the presence of relatively normal object recognition. Together with older lesion studies, recent brain-imaging results provide evidence for the closely related representations of faces and objects and, more recently, for brain areas sensitive to faces and bodies. This evidence raises the issue of whether developmental prosopagnosics may also have an impairment in encoding bodies. We investigated the first stages of face, body, and object perception in four developmental prosopagnosics by comparing event-related potentials to canonically and upside-down presented stimuli. Normal configural encoding was absent in three of four developmental prosopagnosics for faces at the P1 and for both faces and bodies at the N170 component. Our results demonstrate that prosopagnosics do not have this normal processing routine readily available for faces or bodies. A profound face recognition deficit characteristic of developmental prosopagnosia may not necessarily originate in a category-specific face recognition deficit in the initial stages of development. It may also have its roots in anomalous processing of the configuration, a visual routine that is important for other stimuli besides faces. Faces and bodies trigger configuration-based visual strategies that are crucial in initial stages of stimulus encoding but also serve to bootstrap the acquisition of more feature-based visual skills that progressively build up in the course of development.

Emotion and attention: Event-related brain potential studies

DOI:10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56002-9

URL

PMID:17015073

[本文引用: 2]

Emotional pictures guide selective visual attention. A series of event-related brain potential (ERP) studies is reviewed demonstrating the consistent and robust modulation of specific ERP components by emotional images. Specifically, pictures depicting natural pleasant and unpleasant scenes are associated with an increased early posterior negativity, late positive potential, and sustained positive slow wave compared with neutral contents. These modulations are considered to index different stages of stimulus processing including perceptual encoding, stimulus representation in working memory, and elaborate stimulus evaluation. Furthermore, the review includes a discussion of studies exploring the interaction of motivated attention with passive and active forms of attentional control. Recent research is reviewed exploring the selective processing of emotional cues as a function of stimulus novelty, emotional prime pictures, learned stimulus significance, and in the context of explicit attention tasks. It is concluded that ERP measures are useful to assess the emotion鈥揳ttention interface at the level of distinct processing stages. Results are discussed within the context of two-stage models of stimulus perception brought out by studies of attention, orienting, and learning.

The selective processing of briefly presented affective pictures: An ERP analysis

DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00174.x

URL

PMID:15102130

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Recent event-related potential (ERP) studies revealed the selective processing of affective pictures. The present study explored whether the same phenomenon can be observed when pictures are presented only briefly. Toward this end, pleasant, neutral, and unpleasant pictures from the International Affective Pictures Series were presented for 120 ms while event related potentials were measured by dense sensor arrays. As observed for longer picture presentations, brief affective pictures were selectively processed. Specifically, pleasant and unpleasant pictures were associated with an early endogenous negative shift over temporo-occipital sensors compared to neutral images. In addition, affective pictures elicited enlarged late positive potentials over centro-parietal sensor sites relative to neutral images. These data suggest that a quick glimpse of emotionally relevant stimuli appears sufficient to tune the brain for selective perceptual processing.

Dynamics of visual information integration in the brain for categorizing facial expressions

DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.048

URL

PMID:17869111

[本文引用: 1]

A key to understanding visual cognition is to determine when, how, and with what information the human brain distinguishes between visual categories. So far, the dynamics of information processing for categorization of visual stimuli has not been elucidated. By using an ecologically important categorization task (seven expressions of emotion), we demonstrate, in three human observers, that an early brain event (the N170 Event Related Potential, occurring 170 ms after stimulus onset [1–16]) integrates visual information specific to each expression, according to a pattern. Specifically, starting 50 ms prior to the ERP peak, facial information tends to be integrated from the eyes downward in the face. This integration stops, and the ERP peaks, when the information diagnostic for judging a particular expression has been integrated (e.g., the eyes in fear, the corners of the nose in disgust, or the mouth in happiness). Consequently, the duration of information integration from the eyes down determines the latency of the N170 for each expression (e.g., with “fear” being faster than “disgust,” itself faster than “happy”). For the first time in visual categorization, we relate the02dynamics of an important brain event to the dynamics of a precise information-processing function.

The neural correlates of perceiving human bodies: An ERP study on the body-inversion effect

DOI:10.1097/00001756-200404090-00007

URL

PMID:15073513

[本文引用: 1]

The present study investigated the neural correlates of perceiving human bodies. Focussing on the N170 as an index of structural encoding, we recorded event-related potentials (ERPs) to images of bodies and faces (either neutral or expressing fear) and objects, while subjects viewed the stimuli presented either upright or inverted. The N170 was enhanced and delayed to inverted bodies and faces, but not to objects. The emotional content of faces affected the left N170, the occipito-parietal P2, and the fronto-central N2, whereas body expressions affected the frontal vertex positive potential (VPP) and a sustained fronto-central negativity (300-500 ms). Our results indicate that, like faces, bodies are processed configurally, and that within each category qualitative differences are observed for emotional as opposed to neutral images.

The impact of perceptual load on the non-conscious processing of fearful faces

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0154914

URL

PMID:27149273

[本文引用: 1]

Emotional stimuli can be processed without consciousness. In the current study, we used event-related potentials (ERPs) to assess whether perceptual load influences non-conscious processing of fearful facial expressions. Perceptual load was manipulated using a letter search task with the target letter presented at the fixation point, while facial expressions were presented peripherally and masked to prevent conscious awareness. The letter string comprised six letters (X or N) that were identical (low load) or different (high load). Participants were instructed to discriminate the letters at fixation or the facial expression (fearful or neutral) in the periphery. Participants were faster and more accurate at detecting letters in the low load condition than in the high load condition. Fearful faces elicited a sustained positivity from 250 ms to 700 ms post-stimulus over fronto-central areas during the face discrimination and low-load letter discrimination conditions, but this effect was completely eliminated during high-load letter discrimination. Our findings imply that non-conscious processing of fearful faces depends on perceptual load, and attentional resources are necessary for non-conscious processing.

Face-body integration of intense emotional expressions of victory and defeat

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0171656

URL

PMID:5330456

[本文引用: 1]

Human facial expressions can be recognized rapidly and effortlessly. However, for intense emotions from real life, positive and negative facial expressions are difficult to discriminate and the judgment of facial expressions is biased towards simultaneously perceived body expressions. This study employed event-related potentials (ERPs) to investigate the neural dynamics involved in the integration of emotional signals from facial and body expressions of victory and defeat. Emotional expressions of professional players were used to create pictures of face-body compounds, with either matched or mismatched emotional expressions in faces and bodies. Behavioral results showed that congruent emotional information of face and body facilitated the recognition of facial expressions. ERP data revealed larger P1 amplitudes for incongruent compared to congruent stimuli. Also, a main effect of body valence on the P1 was observed, with enhanced amplitudes for the stimuli with losing compared to winning bodies. The main effect of body expression was also observed in N170 and N2, with winning bodies producing larger N170/N2 amplitudes. In the later stage, a significant interaction of congruence by body valence was found on the P3 component. Winning bodies elicited lager P3 amplitudes than losing bodies did when face and body conveyed congruent emotional signals. Beyond the knowledge based on prototypical facial and body expressions, the results of this study facilitate us to understand the complexity of emotion evaluation and categorization out of laboratory.

Interaction of facial expressions and familiarity: ERP evidence

DOI:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.10.001

URL

PMID:17997008

[本文引用: 1]

There is mounting evidence that under some conditions the processing of facial identity and facial emotional expressions may not be independent; however, the nature of this interaction remains to be established. By using event-related brain potentials (ERP) we attempted to localize these interactions within the information processing system. During an expression discrimination task (Experiment 1) categorization was faster for portraits of personally familiar vs. unfamiliar persons displaying happiness. The peak latency of the P300 (trend) and the onset of the stimulus-locked LRP were shorter for familiar than unfamiliar faces. This implies a late perceptual but pre-motoric locus of the facilitating effect of familiarity on expression categorization. In Experiment 2 participants performed familiarity decisions about portraits expressing different emotions. Results revealed an advantage of happiness over disgust specifically for familiar faces. The facilitation was localized in the response selection stage as suggested by a shorter onset of the LRP. Both experiments indicate that familiarity and facial expression may not be independent processes. However, depending on the kind of decision different processing stages may be facilitated for happy familiar faces.

The ERPs for the facial expression processing

面部表情加工的ERP成分

Can we distinguish emotions from faces? Investigation of implicit and explicit processes of peak facial expressions

Three stages of emotional word processing: An ERP study with rapid serial visual presentation

DOI:10.1093/scan/nst188

URL

PMID:24526185

[本文引用: 4]

Rapid responses to emotional words play a crucial role in social communication. This study employed event-related potentials to examine the time course of neural dynamics involved in emotional word processing. Participants performed a dual-target task in which positive, negative and neutral adjectives were rapidly presented. The early occipital P1 was found larger when elicited by negative words, indicating that the first stage of emotional word processing mainly differentiates between non-threatening and potentially threatening information. The N170 and the early posterior negativity were larger for positive and negative words, reflecting the emotional/non-emotional discrimination stage of word processing. The late positive component not only distinguished emotional words from neutral words, but also differentiated between positive and negative words. This represents the third stage of emotional word processing, the emotion separation. Present results indicated that, similar with the three-stage model of facial expression processing; the neural processing of emotional words can also be divided into three stages. These findings prompt us to believe that the nature of emotion can be analyzed by the brain independent of stimulus type, and that the three-stage scheme may be a common model for emotional information processing in the context of limited attentional resources.

Single-trial ERP evidence for the three-stage scheme of facial expression processing

面孔表情加工三阶段模型的单试次ERP证据

Individual differences in detecting rapidly presented fearful faces

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0049517

URL

PMID:3498139

[本文引用: 1]

Rapid detection of evolutionarily relevant threats (e.g., fearful faces) is important for human survival. The ability to rapidly detect fearful faces exhibits high variability across individuals. The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between behavioral detection ability and brain activity, using both event-related potential (ERP) and event-related oscillation (ERO) measurements. Faces with fearful or neutral facial expressions were presented for 17 ms or 200 ms in a backward masking paradigm. Forty-two participants were required to discriminate facial expressions of the masked faces. The behavioral sensitivity index d' showed that the detection ability to rapidly presented and masked fearful faces varied across participants. The ANOVA analyses showed that the facial expression, hemisphere, and presentation duration affected the grand-mean ERP (N1, P1, and N170) and ERO (below 20 Hz and lasted from 100 ms to 250 ms post-stimulus, mainly in theta band) brain activity. More importantly, the overall detection ability of 42 subjects was significantly correlated with the emotion effect (i.e., fearful vs. neutral) on ERP (r66=660.403) and ERO (r66=660.552) measurements. A higher d' value was corresponding to a larger size of the emotional effect (i.e., fearful – neutral) of N170 amplitude and a larger size of the emotional effect of the specific ERO spectral power at the right hemisphere. The present results suggested a close link between behavioral detection ability and the N170 amplitude as well as the ERO spectral power below 20 Hz in individuals. The emotional effect size between fearful and neutral faces in brain activity may reflect the level of conscious awareness of fearful faces.

Comparison of facial expressions and body expressions: An event-related potential study

恐惧情绪面孔和身体姿势加工的比较: 事件相关电位研究

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2015.00963

URL

[本文引用: 4]

面孔和身体姿势均为日常交往中情绪性信息的重要载体,然而目前对后者的研究却很少。本文采用事件相关电位(ERP)技术,考察了成年被试对恐惧和中性身体姿势的加工时程,并将此与同类表情的面孔加工ERP结果进行比较。结果发现,与情绪性面孔加工类似,大脑对情绪性身体姿势的加工也是快速的,早在P1阶段即可将恐惧和中性的身体姿势区分开来,同时身体姿势图片比面孔图片诱发了更大的枕区P1成分。与情绪性面孔相比,情绪性身体姿势诱发出的N170和VPP幅度较小,潜伏期较短,这两个ERP成分能区分恐惧和中性的面孔,但不能区分恐惧和中性的身体姿势,说明在情绪性信息加工的中期阶段,大脑在身体姿势加工方面的优势不如在面孔加工方面的优势大。最后,在加工的晚期阶段,P3可区分情绪载体和情绪类别,且在两个主效应上均产生了较大的效应量,体现了大脑在此阶段对情绪性信息的更深入的加工。本研究提示,情绪性身体姿势和面孔的加工具有相似性,但与情绪性面孔相比,大脑似乎对情绪性身体姿势的加工在早期阶段(P1时间窗)更有优势。本文对情绪性面孔和身体姿势的结合研究将有助于深入了解情绪脑的工作机制,同时找到更多的情绪相关的生物标记物以帮助临床诊断具有情绪认知障碍的精神病患者的脑功能缺损。