1 问题提出

自我监控(self-monitoring)作为一种人格特质, 描述的是个体在不同情境中调整自己的行为以适应特定情境需要的一种倾向(Synder, 1974)。高自我监控者善于管理自身的情绪表达, 在人际交往中会表现出更强的适应能力(e.g., Diefendorff, Croyle, & Gosserand, 2005; Wang, Hu, & Dong, 2015)。在群体背景下, 自我监控对于人际关系的建立尤为重要; 特别是在群体形成和发展的阶段, 自我监控不仅影响个人在群体中人际关系构建的有效性, 同时也可能影响到群体互动的质量。

以往研究发现了群体中的高自我监控者的优势, 比如更具有成为领导者的潜质(Zaccaro, Foti, & Kenny, 1991), 在人际网络中会占据更有利的位置(Mehra, Kilduff, & Brass, 2001; Oh & Kilduff, 2008)。但是, 已有研究仅仅考察了自我监控对于群体中的个体的作用, 却忽略了自我监控在群体层面的影响。群体研究表明, 群体的个性构成(personality composition)会影响群体过程, 进而影响群体的绩效表现(Bell, 2007; Colbert, Barrick, & Bradley, 2014; Lin & Rababah, 2014)。那么, 群体自我监控的构成——群体的平均自我监控水平, 是否会通过影响群体内成员互动的质量, 从而间接影响他们在群体任务中的表现?探讨群体的自我监控构成对群体互动及群体结果的影响将能深化对自我监控本质的认识, 拓展自我监控理论的解释范畴。此外, 在群体建立到发展的过程中, 自我监控这一人格特质对人际互动的作用可能会发生变化。然而, 已有研究基本假定自我监控的作用是稳定的, 忽略了在群体发展的不同阶段自我监控发挥的作用大小可能有所不同。

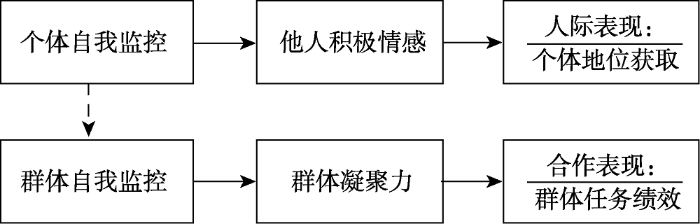

为了弥补上述不足, 本研究将采用动态视角, 在个体水平和群体水平探讨自我监控对人际互动质量的作用。在个体水平, 我们关注自我监控如何影响个体的人际表现——个体地位(status)和友谊网络中心度(friendship network centrality), 两者共同刻画了个体在群体中的地位水平; 在群体水平, 我们关注群体自我监控的构成如何影响群体的合作表现——群体合作中的任务绩效(task performance)。个体在群体中的地位水平和群体在合作任务中的绩效表现都是社会互动质量在群体背景下的重要标志, 并且与自我监控这一人格特质有着密切的关联。

1.1 群体内:自我监控对个体人际表现的影响

群体中的个体在个性特征、价值观、行为习惯等方面存在差异。个体要在群体中获得高质量的人际关系, 首先需要去理解不同成员的特点, 从而采取适宜的沟通和行为方式。相比低自我监控者, 高自我监控者更善于观察和理解与他人相关的信息。Synder和Cantor (1980)发现高自我监控者更善于描绘他人形象, 而低自我监控者更善于描绘自我形象。这表明高自我监控者能够准确把握不同群体成员的特点, 并以此为行为线索表现出令对方喜欢的行为。其次, 已有研究也发现高自我监控者更善于运用幽默来表达观点(Turner, 1980), 恰当地控制交谈节奏(Dabbs, Evans, Hopper, & Purvis, 1980), 进而促进群体其他成员在与高自我监控者的社会交往中的愉悦程度。此外, 高自我监控者在自我展示时会更多表现积极情绪, 更少展现消极情绪(Ickes, Holloway, Stinson, & Hoodenpyle, 2006)。由于寝室成员生活接触频繁, 很容易产生情绪传染, 因此寝室中的其他成员在和高自我监控者相处会更多感受到积极情绪。

由此推测, 相比低自我监控者, 高自我监控者更有可能在群体内让他人对自己持有积极情感(positive sentiments)。情感是对特定个体或事物的效价评估, 反映了对该个体或事情的喜欢或不喜欢(Frijda, 1994; Kelly & Barsade, 2001)。遵循Scott, Colquitt和Zapata-Phelan (2007)的做法, 本研究将积极情感定义为其他群体成员预期或实际与某一个体互动时所引发的积极情绪反应——愉快(joviality)和自信(self-assurance)。愉快包含快乐(happiness)和激情(enthusiasm)的感受, 自信则包含骄傲(pride)和信心(confidence)的感受(Watson, 2000)。高自我监控者他人导向的人际互动方式会让与之相处的群体成员感受到更多的积极情绪, 因而形成对该成员的积极情感。

此外, 我们认为自我监控对他人积极情感的正向作用可能会随着时间的推移而增强。在群体形成的初期, 成员之间的交流有限, 彼此的交往也比较谨慎, 以维持表面的和谐关系。但是随着群体的发展, 群体内成员的个人特质在互动中会不断表露。此时, 高自我监控者由于倾向于捕捉与他人有关的信息(Synder & Cantor, 1980), 因而可以更有效地理解他人的个人喜好、行为习惯、性格等, 并在与他人交往时更有针对性地使用人际沟通的技巧, 让他人感到更多的积极情绪。相反, 对于低自我监控者, 由于他们更关注与自我有关的信息(Synder & Cantor, 1980), 他人的自我表露并不能有效地提高他们对群体内其他成员的理解。与此同时, 由于低自我监控者更倾向于以自我的感受、喜好来展现自己的行为(Gangestad & Snyder, 2000), 随着群体的发展他们更有可能与他人发生冲突, 令他人感到不悦。综上所述, 我们提出如下假设:

假设1:个体自我监控水平正向预测他人积极情感; 并且其预测力随时间推移而增强。

在群体中, 人际关系成功的一个重要标志就是地位获取。地位反映了个体在群体中获得的尊重和享有的威望(Magee & Galinsky, 2008)。高地位的个体会获得更多的资源, 对群体决策产生更大的影响, 更容易使他人顺从, 因此获得高地位是个体在群体中的一个重要目标(Pettit, Yong, & Spataro, 2010)。人们是否赋予某一个体较高的地位可能受到情绪的影响。当在与某一个体的相处中体验到积极情绪时, 人们会更关注该个体, 也会更愿意与之相处、受其影响。人际互动中体验到的积极情绪是一种重要的资源(Fredrickson, 1998)。人们希望获取并保存自己的资源, 因此会更倾向于与那些让自己体验到积极情绪的人相处(Hobfoll, 1989), 并由于喜欢甚至依赖而赋予其更高的个体地位。

除了群体成员因顺从而赋予个体地位之外, 在网络结构中的地位——友谊网络中心度(Baldwin, Bedell, & Johnson, 1997)也是一项衡量个体在群体中地位的重要指标。正如上文所述, 当人们在与某一个体相处时体验到更多的积极情绪时, 会更愿意与该个体交往, 更可能与其发展出亲密的朋友关系; 该个体因此会获得更高的友谊网络中心度。在群体中, 个体的自我监控水平越高, 人们越会对该个体持有积极情感。所以, 自我监控水平会通过提高他人的积极情感从而对个体在群体内的地位获取(个体地位和友谊网络中心度)起到正向的间接效应。

假设2:个体自我监控水平通过群体内他人的积极情感对个体地位获取(个体地位和友谊网络中心度)产生间接的正向作用。

1.2 群体间:自我监控对群体合作表现的影响

以往研究主要比较了不同自我监控水平的个体在人际互动、工作表现上的差异(e.g., Scott, Barnes, & Wagner, 2012; Turnley & Bolino, 2001), 但对于自我监控在群体层面的效应却探讨甚少。群体的平均自我监控水平越高, 表明群体中的个体整体上更善于根据情境的和人际的线索来指导自己的行为(Synder, 1974)。在这种情况下, 我们认为群体更可能形成较强的凝聚力(cohesion)。一方面, 当群体成员都能较好地调控自己的行为时, 不同成员之间会产生更加愉悦的互动、形成更好的人际吸引, 成员之间会更愿意一起开展合作。另一方面, 在面临冲突的时候, 高自我监控者也更有能力通过合作和妥协去解决问题(Zaccaro et al., 1991); 群体平均自我监控水平越高, 意味着成员间更能有效解决冲突, 避免冲突升级对团队凝聚力的伤害。综合来看, 群体自我监控水平会对群体凝聚力产生积极的影响。

此外, 群体自我监控对群体凝聚力的影响也将随着时间推移而增强。在群体成立的初期, 由于成员们刚进入一个新的社交环境, 他们会采取暂时性印象管理的策略; 但是在群体逐步发展和成熟的过程中, 群体会经历更多的事件(如集体活动、冲突等), 特质自我监控的作用就会逐渐显现。成员们整体的自我监控水平越高, 他们越能在长期的活动中保持适宜的行为和交流方式, 从而发展成有凝聚力的群体; 但当成员们整体的自我监控水平较低时, 成员们无法继续维持早期的表面和谐, 这将对群体凝聚力造成负面影响。也就是说, 自我监控水平高的群体和自我监控水平低的群体在群体凝聚力上的差异会随群体发展而凸显。综上所述, 我们提出如下假设:

假设3:群体成员的平均自我监控水平正向预测群体凝聚力; 并且其预测力随时间推移而增强。

群体的凝聚力越高, 群体成员间往往有更强的联系, 有更高的集体概念, 有更大的向心力(Man & Lam, 2003)。群体凝聚力有利于促进群体成员间的协调, 使群体合作更加顺畅(Mullen & Copper, 1994)。在高凝聚力的群体中, 群体成员会有更强的目标承诺, 会付出更大的个人努力以实现群体目标(Klein & Mulvey, 1995)。凝聚力带来的这些积极后果有利于群体成员更好地完成群体任务, 特别是在需要成员之间较多沟通与协调的合作型的任务中, 高凝聚力的群体往往会有更好的绩效表现。以往的实证研究也较好地支持了凝聚力对群体绩效的积极效应(Beal, Cohen, Burke, & McLendon, 2003; Filho, Dobersek, Gershgoren, Becker, & Tenenbaum, 2014)。

考虑到群体自我监控水平对群体凝聚力的促进作用, 我们提出群体自我监控水平可能通过提高群体凝聚力从而对群体任务绩效产生间接的积极影响。

假设4:群体成员的平均自我监控水平通过群体凝聚力对群体的任务绩效产生间接的正向作用。

图1呈现了本研究的主要研究内容。

图1

2 研究方法

2.1 参与者和程序

我们选取了北京大学的大一新生寝室为研究对象, 在2016年9~12月对他们进行了跟踪调查。选取大一新生寝室为调查对象主要基于以下几方面的考虑。第一, 新生寝室可以尽可能控制不同群体之间在群体内异质性上的差异, 寝室内成员性别相同、年龄相仿。第二, 新生寝室是一个没有明确目标和确定社会规范的群体, 是一个弱环境, 更有利于观察特质的影响。第三, 新生寝室属于刚组建的群体, 对他们做跟踪调查有利于观测因果关系, 跟踪调查的方式也能够探究自我监控的动态效应。基于以上考虑, 在新生入学第一周, 我们招募了40个新生寝室(18个男生寝室和22个女生寝室)参与调查, 共159人, 其中男生71人(一个男生寝室为三人寝室)。我们分别在第3周(T1), 第9周(T2), 第15周(T3)进行了三次问卷调查, 每次数据采集均在5天内完成。最终一共有32个寝室(12个男生寝室)、122名新生(45名男生)参与了完整的三次调查。

2.2 变量测量

2.2.1 个体水平

个体自我监控(T1):个体自我监控的测量采用了Lennox和Wolfe (1984) 13个条目的量表。条目如“在社交场合, 如果我感觉有必要, 我有能力改变我的行为”, “我能够通过别人的眼睛准确判断他们的真实情绪” (1=非常不符, 7=非常符合)。量表的Cronbach’s α系数为0.87。

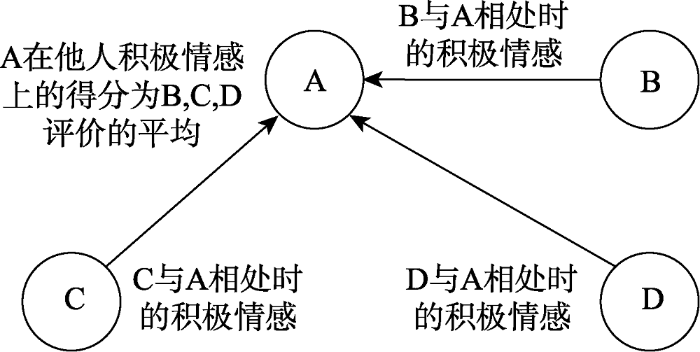

他人积极情感(T2):遵循Scott等人(2007)的做法, 我们从Positive and Negative Affect Schedule- Expanded (PANAS-X, Watson & Clark, 1994)表中抽取了4个条目来测量他人对特定个体的积极情感。在测量时, 我们让参与者依次评价与其他各个寝室成员相处时的情绪感受——“当我和他/她在一起时, 我感到:高兴的/充满激情的/自豪的/自信的” (1=非常不符, 7=非常符合)。量表的Cronbach’s α系数为0.80, 所以我们将4个条目求均值。在计算时, 他人对特定个体的积极情感(T2)是取寝室其他成员针对该个体所做出的评价的平均。如图2所示, A在他人积极情感上的得分是将B, C, D三人评价的在与A一起时的情绪感受取平均分得到, 以此类推B, C, D在他人积极情感上的得分。我们计算了Rwg (within-group interrater reliability)和ICC (1) (intraclass correlation coefficient)这两个衡量组内不同评价者之间评价一致性的重要指标(LeBreton & Senter, 2008)。结果显示Rwg的中位值是0.97, ICC (1)值为0.60, 表明在一个组(寝室)内, 其他成员针对某个特定成员所做出的评价有良好的组内一致性, 可以把其他成员针对特定个体的评价聚合从而衡量该个体的他人积极情感(T2) (James, 1982)。

图2

他人积极情感(T3):他人积极情感(T3)采用了和他人积极情感(T2)相同的测量方式。量表的Cronbach’s α系数为0.81。Rwg的中位值是0.98, ICC (1)值为0.62。

个体地位(T3):根据 Anderson, John, Keltner和Kring (2001)以及Bendersky和Shah (2012)的做法, 我们采用三个条目来测量个体在寝室中的地位。我们让参与者依次对其他各个寝室成员做出评价。具体条目为“该室友在寝室很有威望”, “该室友在寝室很受尊敬”, “该室友在寝室很有影响力” (1=非常不符, 7=非常符合)。某一个体的地位等于寝室内其他成员对该个体地位评价的平均。量表的Cronbach’s α系数为0.87。Rwg的中位值是0.97, ICC (1)值为0.58, 表明一个组(寝室)内, 其他成员对某个特定成员的地位评价具有良好的组内一致性, 因此我们将其他成员对被评者的评价聚合来反映被评者的个体地位。

友谊网络中心度(T3):让每个参与者评价其他寝室成员, “该成员是不是你生活中的朋友(生活中一起娱乐、运动等) (1=是, 0=否)?”某个个体的友谊网络中心度等于寝室内将其当作朋友的成员的总数(Klein, Lim, Saltz, & Mayer, 2004)。

2.2.2 群体水平

群体自我监控(T1):在本研究中, 群体自我监控采用了群体内个体自我监控水平的平均分。以往关于群体层面个性构成的研究主要有三种操作范式(LePine, 2003):(1)加成模型(additive model)——成员平均分; (2)联合模型(conjunctive model)——最低分者的分数; (3)分离模型(disjunctive model) ——最高分者的分数。就本研究而言, 我们采用加成模型主要基于以下几点理由:第一, 联合模型适用于当组与组的差异来自于最低分者时, 分离模型适用于当组与组的差异来自最高分者时(LePine, 2003)。群体凝聚力的形成是基于成员彼此之间的互动的, 因此个别的高自我监控者或低自我监控者可能并不足以决定群体凝聚力, 而成员总体的自我监控水平会更具有影响力。第二, 我们发现平均分数(加成模型)与最低分(联合模型)和最高分(分离模型)高相关。总体上, 群体自我监控的平均分与最高分(r = 0.68, p < 0.001)和最低分(r = 0.56, p < 0.001)都高相关, 这表明平均分与另外两种替代性计算方法存在很大的重叠。第三, 以往研究表明加成模型对结果的预测更具有代表性, 即能在不同的任务情境中预测结果(e.g., Tziner & Eden, 1985; Devine & Philips, 2000)。此外, 采用加成方式也符合已有文献的做法(Roberson & Williamson, 2012)。综合以上考虑, 在本研究中, 我们采用了所有成员自我监控水平的平均值来衡量群体自我监控。个性特征是每个个体固有的属性, 一般而言不会在群体成员间收敛(converge), 因此对于这种加成方式不需要计算评价者的一致性(e.g., Bradley, Klotz, Postlethwaite, & Brown 2013; Lin & Rababah, 2014)。

群体凝聚力(T2):群体凝聚力(T2)由每个成员对寝室的凝聚力做出单独的评价, 再对寝室内所有成员的评价取平均得到。具体量表采用了两个条目(Jehn & Mannix, 2001), 分别是“我们寝室有很强的凝聚力”、“我们寝室的成员具有团队精神” (1=非常不符, 7=非常符合)。Cronbach’s α系数为0.95。Rwg的中位值是0.88, ICC (1)值为0.25。

群体凝聚力(T3):群体凝聚力(T3)采用了和群体凝聚力(T2)相同的测量。Cronbach’s α系数为0.95。Rwg的中位值是0.89, ICC (1)值为0.24。群体凝聚力(T2)和群体凝聚力(T3)在Rwg和ICC (1)上的得分表明寝室成员对寝室的凝聚力感知具有较好的内部一致性, 聚合到群体层面是合理的。

群体任务绩效(T3):群体任务绩效采用了客观的行为测量。第三次数据收集在实验室中进行。寝室成员首先完成问卷调查, 然后进行团队任务——拼图游戏。该拼图游戏改编自刘雪峰和张志学(2005)的管理生产练习。在这个游戏中, 所有寝室成员将分成两种角色(D和W)来合作完成一个拼图任务。D组(2人)能看到拼图的设计图纸, 需要在20分钟的时间限制内向W组沟通, 但只能使用语言, 不可以让W组直接看到图纸, 不可以自己动手画图给W组, 也不可以用手势比形状。W组(1~2人)看不到拼图的设计图纸, 可以用纸笔记录从D组获取的信息。

任务的具体实施流程可分解为四个阶段:(1)寝室成员自由选择不同角色, 然后根据角色被分到两个不同的小房间; (2)主试将设计图纸交给D组, D组单独讨论如何向W组讲述图纸; (3) D组进入W组房间与W组进行面对面沟通, 描述设计图纸; (4)沟通结束, D组离场, 主试将打乱的小块拼图发放给W组, W组完成拼图。这个拼图任务需要寝室成员互相了解彼此的优势不足, 合理分配角色, 也需要D组和W组双方有效传达信息、给予反馈、针对反馈进行澄清或调整自己的沟通方式。因此这个群体合作的任务在各个阶段都要求群体内部成员之间具有良好的了解、沟通和默契, 能够考量群体内是否具有长期的、良好的社会互动。

我们用是否完成拼图以及完成拼图的时间来衡量任务绩效。由于所有寝室都完成了拼图, 最终的任务绩效(T3)由任务花费总时长(单位分钟)来衡量。时间越短, 绩效越好; 为了方便结果的理解, 我们在假设检验时将时间乘以-1 来表示群体任务绩效。

2.3 分析策略

对于个体层面的研究假设, 由于个体都嵌入在不同的群体中, 为了控制组间差异造成的影响, 采用跨层次线性模型(hierarchical linear modeling, HLM)进行假设检验。对于群体层面的研究假设, 将采用一般线性回归进行假设检验。所有的间接效应都利用RMediation (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011)进行检验。RMediation能够更准确地估计第一类错误, 比传统的检验方法(如Sobel检验)更有效(MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007; MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004)。

3 研究结果

3.1 描述性分析

表1呈现了个体层面变量的相关关系。个体自我监控(T1)与第2个时点的他人积极情感(T2)和第3个时点的他人积极情感(T3)都正相关, 并且与后者的相关性更强, 这为假设1提供了初步的支持。他人积极情感(T2)/他人积极情感(T3)与个体地位(T3)和友谊网络中心度(T3)分别显著正相关, 这也符合预期。个体自我监控(T1)与个体地位(T3)和友谊网络中心度(T3)都不存在显著的相关关系, 表明自我监控水平对两种地位的影响不存在直接效应。

表1 个体层面变量均值、标准差和相关系数

| 变量 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 个体自我监控(T1) | 4.69 | 0.67 | ||||

| 2. 他人积极情感(T2) | 4.84 | 0.92 | 0.18* | |||

| 3. 他人积极情感(T3) | 4.90 | 0.92 | 0.31*** | 0.64*** | ||

| 4. 个体地位(T3) | 5.08 | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.41*** | 0.62*** | |

| 5. 友谊网络中心度 (T3) | 0.78 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.28** | 0.32*** | 0.29** |

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001。

表2呈现了群体层面变量的相关关系。群体自我监控(T1)与第2个时点的群体凝聚力(T2)和第3个时点的群体凝聚力(T3)都呈正相关, 但与后者的相关性并没有强于前者, 不符合预期。群体凝聚力(T2)/群体凝聚力(T3)与群体任务绩效(T3)显著正相关, 符合预期。群体自我监控(T1)与群体任务绩效(T3)不存在显著的相关关系, 表明群体自我监控水平对群体任务绩效的影响不存在直接效应。

表2 群体层面变量均值、标准差和相关系数

| 变量 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 群体自我监控 (T1) | 4.69 | 0.30 | |||

| 2. 群体凝聚力(T2) | 5.49 | 0.91 | 0.49** | ||

| 3. 群体凝聚力(T3) | 5.54 | 0.91 | 0.45* | 0.60*** | |

| 4. 群体任务绩效 (T3) | 11.64 | 3.91 | 0.28 | 0.45** | 0.45** |

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001。

3.2 排除无关变量

在采用回归分析检验假设之前, 我们首先对可能的干扰因素进行了排除。首先, 我们排除了性别的影响。在我们的样本中, 男生的自我监控水平(M = 4.62, SD = 0.10)与女生的自我监控水平(M = 4.73, SD = 0.07)不存在显著差异, t(120) = -0.91, p = 0.362。这也符合Day, Schleicher, Unckless和Hiller (2002)在元分析中的发现——在使用Lennox和Wolfe (1984) 13个条目的量表时, 性别与自我监控水平无关。此外, 无论在个体还是群体层面, 性别与他人积极情感、个体地位、友谊网络中心度、群体凝聚力、群体任务绩效均无显著相关(ps > 0.455)。其次, 我们排除了认知能力对于群体合作任务表现的影响。我们获取了大一新生在各自省份的高考排名, 这种规范化考试成绩被研究证明与一般认知能力显著相关(Frey & Detterman, 2004), 因此可以将高考排名作为一般认知能力的代理变量。分析结果发现, 高考排名与群体凝聚力和任务绩效并无显著相关(ps > 0.611)②(2在我们的样本中, 40.6%的新生高考分数在其所在省份内位列前50名, 59.9%的新生高考排名在其所在省份内位列前100名。我们生成了两个哑变量(dummy variable)——是否省内前50 (1=是, 0=否)和是否省内前100 (1=是, 0=否)。我们再计算每个寝室内成员高考排名是省前50的比例和省前100的比例。最后, 我们拿寝室省前50比例和省前100比例作为群体平均认知水平的指标, 分别与群体自我监控水平(T1)、群体凝聚力(T2)、群体任务绩效(T3)做相关。我们发现, 群体省前50比例与群体自我监控水平(T1) (r = 0.06, p = 0.746)、群体凝聚力(T2) (r = 0.07, p = 0.718)和群体任务绩效(T3) (r = 0.03, p = 0.886)均不相关; 群体省前100比例与群体自我监控水平(T1) (r = 0.03, p = 0.852)、群体凝聚力(T2) (r = -0.13, p = 0.467)和群体任务绩效(T3) (r = 0.09, p = 0.611)均不相关。出现上述结果的可能原因有以下几点:(1)我们的研究样本属于高考表现较好的学生, 这些学生虽然存在排名的差异, 但其认知能力可能并不存在显著的差异; (2)我们的任务对这些大一新生而言并没有构成很大的智力挑战, 因此认知能力在这里并不是核心要素, 成员间的沟通与协作才是影响任务表现的关键因素。这表明我们在样本选择和任务设计上的优势, 尽可能排除了认知能力等其他因素的干扰, 从而更好地考察自我监控这一与人际互动有关的人格特质的作用。)。最后, 我们考察了共同兴趣爱好等对群体凝聚力的影响。对于大学生来说, 饮食和娱乐活动的差异性是影响他们能否进行密切的交流的重要影响因素, 可能会对群体凝聚力造成影响。在第二次调查中, 参与者回答了“你与室友在饮食习惯上是否存在差异”以及“你与室友在娱乐活动上是否存在差异” (1=完全不同, 7=完全吻合)。结果发现, 群体饮食习惯相似性、群体娱乐活动相似性和群体凝聚力无显著相关(ps > 0.148)。

3.3 回归分析

在检验个体层面的假设之前, 我们首先用零模型估计了个体地位的组间差异, Too = 0.20, p < 0.01, ICC (1) = 0.268, 表明26.8%的变异被组间解释。所以有必要采用HLM来检验与地位相关的假设。对友谊网络中心度的估计不存在显著的组间差异, Too = 0.12, p = 0.111, 但为了保持检验方法的一致性, 我们统一用HLM做检验。③(3我们用一般线性回归作为替代方法对个体层面的假设进行了稳健性检验, 结果保持一致。)

表3呈现了HLM的分析结果。模型1中, 个体自我监控(T1)与他人积极情感(T2)有显著的正向关系。为了检验自我监控发生影响的时间效应, 在模型2中, 我们控制了第2个时点的他人积极情感(T2), 再用个体自我监控(T1)来预测第3个时点的他人积极情感(T3)。结果显示, 他人积极情感(T2)与他人积极情感(T3)有显著的正向关系, 并且个体自我监控(T1)与他人积极情感(T3)也存在显著的正向关系。我们进一步用Z检验比较个体自我监控(T1)对他人积极情感(T2)的回归系数与个体自我监控(T1)对他人积极情感(T3)的回归系数, 结果发现后者显著大于前者, Z = 2.52, p < 0.05。这表明, 从第2时点到第3时点, 个体自我监控对他人积极情感的影响有所增强。因此, 假设1得到了支持, 即个体自我监控会促进他人积极情感, 并且这一效应随着时间推移得到增强。

表3 个体层面的跨层次回归分析结果

| 变量 | 模型1 他人积极 情感(T2) | 模型2 他人积极 情感(T3) | 模型3 个人地位(T3) | 模型4 友谊网络 中心度(T3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 个体自我监控 | 0.25* (0.12) | 0.60*** (0.07) | -0.08 (0.12) | -0.03 (0.04) |

| 他人积极情感(T2) | 0.28** (0.09) | 0.42*** (0.09) | 0.10** (0.03) | |

| 样本量(群体水平) | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| 样本量(个体水平) | 122 | 122 | 122 | 122 |

| 偏差(deviance) | 319.93* | 250.27*** | 311.67*** | 64.40** |

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; 报告的是非标准化系数; 括号中报告的是标准误差。

模型3和模型4分别检验了他人积极情感(T2)对个体地位(T3)和友谊网络中心度(T3)的作用。我们选择第2个时点的他人积极情感(T2)而非第3个时点的他人积极情感(T3)是为了尽量减少同源偏差带来的干扰。结果显示, 他人积极情感(T2)分别与个体地位(T3)和友谊网络中心度(T3)存在正向关系。进一步用RMediation检验个体自我监控(T1)通过他人积极情感(T2)对个体地位(T3)/友谊网络中心度(T3)产生的间接效应。RMediation通过两个路径系数——个体自我监控(T1)到他人积极情感(T2)的路径系数和他人积极情感(T2)到个体地位(T3)/友谊网络中心度(T3)的路径系数——的乘积来检验间接效应。如表5所示, 95%偏差校正的置信区间(bias-corrected confidence interval)不包括0, 间接效应显著 。

表4呈现了一般线性回归的结果。模型1中, 群体自我监控(T1)与群体凝聚力(T2)有显著的正向关系。模型2控制了第2个时点的群体凝聚力(T2), 用群体自我监控(T1)预测第3个时点的群体凝聚力(T3)。结果显示, 群体凝聚力(T2)与群体凝聚力(T3)有显著的正向关系, 但群体自我监控(T1)与群体凝聚力(T3)不存在显著的正向关系。因此, 假设3得到部分支持, 即群体自我监控水平会促进群体凝聚力, 但这一效应并未随时间推移发生变化。

表4 群体层面一般线性回归分析结果

| 变量 | 模型1 群体凝聚力 (T2) | 模型2 群体凝聚力 (T3) | 模型3 群体任务绩效 (T3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 群体自我监控 | 1.47** (0.48) | 0.62 (0.50) | 0.47 (1.22) |

| 群体凝聚力(T2) | 0.49** (0.17) | 0.89* (0.40) | |

| 样本量 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| R2 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.21 |

| F | 9.22** | 9.13*** | 3.83* |

注:*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; 报告的是非标准化系数; 括号中报告的是标准误差。

模型3检验群体凝聚力(T2)对群体任务绩效(T3)的影响。与个体层面的做法一致, 我们选择第2个时点的群体凝聚力(T2)而非第3个时点的群体凝聚力(T3)是为了尽量减少同源偏差带来的干扰。结果显示群体凝聚力(T2)与群体任务绩效(T3)有显著的正向关系。进一步用RMediation检验群体自我监控(T1)通过群体凝聚力(T2)对群体任务绩效(T3)的间接效应。如表5所示, 95%偏差校正的置信区间不包括0, 间接效应显著。

表5 RMediation检验间接效应的结果

| 路径 | 自变量→ 中介变量(a) | 中介变量→ 因变量(b) | 估计量(a × b) | 偏差校正的 置信区间 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 个体自我监控(T1)-他人积极情感(T2)-个体地位(T3) | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.105 | [0.006, 0.225] |

| 个体自我监控(T1)-他人积极情感(T2)-友谊网络中心度(T3) | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.025 | [0.001, 0.058] |

| 群体自我监控(T1)-群体凝聚力(T2)-群体任务绩效(T3) | 1.47 | 0.89 | 1.308 | [0.105, 3.012] |

注:Bootstrapping = 1,000。

4 讨论

本研究关注自我监控这一人格特质在群体背景下的作用。通过对大学新生寝室的跟踪调查, 我们发现在个体层面, 个体自我监控能够提高他人对该个体的积极情感, 并且这一效应随着时间推移得到增强; 更进一步, 个体自我监控通过提高他人对该个体持有的积极情感间接提高其在群体中的个体地位和友谊网络中心度。在群体层面, 群体自我监控能够提高群体内的凝聚力; 更进一步, 群体自我监控通过提高群体凝聚力间接提高群体任务绩效。

研究假设3的后半部分——自我监控对群体凝聚力的预测力随时间推移而增强——并未得到数据支持。我们认为存在两种可能的解释。第一, 从样本的特征考虑, 随着入学日久, 大学生参与的其他活动越来越多, 每个人的时间安排更加密集, 要凑齐寝室所有成员的时间进行集体活动的难度相比于初期有所提高, 这使得寝室作为整体的集体活动频率下降。也就说, 自我监控对群体凝聚力的影响也许被群体活动频率下降所抵消了。第二, 不同于个体层面的中介变量“他人对某一个体的积极情感”, 群体凝聚力不仅涉及了相处时的愉快感受, 也涉及成员之间互相的承诺和投入; 然而高自我监控者对工作、伴侣的承诺水平并不会更高(Jenkins, 1993; Norris & Zweigenhaft, 1999)。因此, 群体自我监控构成对群体凝聚力的影响可能存在一个“天花板”。我们认为, 上述解释都有可能导致自我监控对群体凝聚力的预测作用维持不变。

4.1 理论贡献

本研究的发现为自我监控以及地位等相关领域做出了以下几点理论贡献。

首先, 通过研究层次的转变, 我们不仅在个体层面探究了个体自我监控对个体人际质量(他人积极情感)和地位获取(个体地位和友谊网络中心度)的影响, 更重要的是在群体层面探究了群体自我监控水平对于群体互动(群体凝聚力)以及群体结果(群体任务绩效)的影响。以往对自我监控的研究主要集中在个体层面, 着重探究高自我监控者有哪些有别于他人的行为表现(e.g., Oh & Kilduff, 2008; Wang et al., 2015)。随着人们越来越多地依赖于群体来开展工作, 我们需要更多地去关注群体的构成, 而不是单一地聚焦在群体中的个体上。然而, 我们对自我监控在群体层面的效应却知之甚少。作为例外, Roberson和Williamson (2012)的研究也只是将群体自我监控作为边界条件, 检验了其是否调节表达性网络强度与过程公平氛围强度的正向关系, 但并没有直接探究群体自我监控构成作为一种群体投入如何影响群体内部的互动, 进而影响群体的结果。通过探讨自我监控这一人格特质在群体水平的构成, 本研究揭示了以往忽略的自我监控的一大积极作用, 即群体自我监控水平越高, 越有利于群体形成较高的凝聚力, 从而对群体的任务表现产生间接的促进作用。

其次, 我们引入动态视角, 探究了自我监控的作用如何随群体发展而变化。在个体层面, 自我监控对人际质量的影响随时间增强还是减弱有两种不同的推理。一方面, 大家从群体成立之初的非常陌生到彼此了解, 性格、观念的相似性等因素可能产生更大的影响, 自我监控特质的影响可能会下降; 另一种可能则是, 群体成立之初, 大家都短暂性地提高了自我监控水平, 但是, 随着群体发展, 只有特质自我监控较高的个体仍然保持情境和社交敏感性, 自我监控特质的影响会增强。我们的研究结果支持了后一种可能性, 自我监控正向促进他人对个体的积极情感, 并且这种效应随着时间推移而增强。采用动态视角具有重要的意义, 因为在人际互动中, 尤其是在群体从建立到发展的过程中, 群体内成员之间的互动的频率和内容是发生变化的(Tuckman, 1965)。比如在群体刚组建的时候, 人们还处于相互试探、建立信任的阶段, 可能会采用印象管理的手段, 削弱了个性特征对于人际质量的影响。但是随着群体的逐步发展, 人们会进行更多的协作, 也会经历一些冲突, 印象管理的程度减少, 个性特征的作用就凸显出来了。我们在个体层面发现的自我监控对他人积极情感的作用随时间而增强的结果, 也较好地印证了这一点。

最后, 本研究的发现对于地位领域也有一定的贡献。过往关于自我监控的研究探讨了高自我监控者在工作领域的一些表现, 例如他们更多展现出灵活性而被选为领导(Hall, Workman, & Marchioro, 1998), 或者更多塑造慷慨的同伴形象(Flynn, Reagans, Amanatullah, & Ames, 2006)从而获得更高的地位。本研究的结论和这些研究具有相似性, 都指向了自我监控可以促进个体地位的提升, 但是我们采取了不同的解释视角。以往的地位研究(以期望状态理论为代表)认为群体中个体地位的形成主要基于人们对特定个体的贡献的预期(Correl & Ridgeway, 2003), 但我们认为在一般的人际互动中, 他人的积极情感也是获取地位的一种重要方式。探讨地位获取的其他途径也是近期理论所关注的一个方向, 例如有研究者认为美德也是获取地位的途径(Bai, 2017)。

4.2 局限及未来研究方向

虽然本研究有不少优势, 但在理论上和方法上也存在一些局限, 是未来研究需要更好地去关注和解决的。

第一, 基于新生寝室的研究结论是否可以扩展到工作团队和其他群体中, 需要未来研究的进一步检验。为了检验自我监控对人际互动的预测力是否有动态变化, 我们选取了大学新生寝室作为研究对象。但是寝室群体与工作团队有相似性也有区别性。尽管学生也会在寝室内部交流学习求职等任务相关的信息, 但寝室整体没有明确任务目标, 更多是人际导向的。因此, 在个体层面的结论——自我监控通过他人的积极情感间接地促进个体地位获取——是否可以在工作团队中推广需要谨慎考虑。在一些工作要求较低、更注重人际关系的工作团队中, 自我监控可能仍然具有作用; 但是在一些任务导向很强的团队中, 自我监控对地位的间接影响是否会被任务贡献所遮蔽, 则需要在未来的研究中继续探讨。在群体层面, 自我监控通过群体凝聚力间接影响了团队的合作绩效, 虽然我们尽可能使用了客观的绩效指标, 但这一实验任务是否能迁移到实际的工作任务中, 也需要谨慎的考虑。

第二, 本研究并未探讨群体中自我监控的作用是否存在边界条件。事实上, 一些群体特征可能会影响自我监控的作用大小。比如, 群体的关系导向越强, 人际交往中的规范越模糊, 成员的相似性越低(潜在冲突的可能性越高), 自我监控的影响力可能会越强, 因为这些情境需要人们在互动中监控他人的行为和感受, 控制自己的情绪和行为反应, 做出更适宜的回应。在本研究中, 寝室是一个关系导向较强的情境, 未来研究可以继续考察规范的清晰度和成员的相似性(例如价值观的差异、专业背景的多样化等)是否会产生影响。更为有趣的是, 本研究主要揭示了自我监控在群体背景下的积极意义, 但自我监控并不总是正面的, 未来研究可以尝试探讨自我监控对于人际互动或者群体互动可能存在的负面影响以及这些负面影响何时会显现等问题。

第三, 本文虽然引入了动态视角, 但没有测量群体互动的变化, 无法从数据上确定自我监控和哪些因素发生了交互作用, 也未能揭示群体互动的具体过程。比如, 个体自我监控对他人积极情感的正向作用随时间增强, 是否是因为随着群体发展, 高自我监控者比低自我监控者更多了解和捕捉到了群体内他人的性格、价值观、行为习惯等信息, 还是由于低自我监控者与群体内其他成员产生了更多的人际冲突?又比如, 群体自我监控对于群体凝聚力的预测作用未能随时间增强, 是由于高自我监控者对寝室的承诺不够强、更多进行了寝室外社交, 还是因为寝室集体活动频率下降, 寝室整体的相处时间减少?这些内部的过程需要未来研究进一步探究。并且, 我们在时间跨度的选取上也有一定局限。本研究对新生寝室进行了一个学期的追踪调查, 我们认为从通常的社交频率来看, 寝室成员朝夕相处, 一个学期的时间长度足够室友之间较深入的了解, 在此时自我监控仍然起到了积极的作用。但是该时间跨度是否足够长, 或者在什么时间范围内, 自我监控对他人积极情感的作用是逐渐增强的, 仍然是难以明确回答的问题。因此, 对于自我监控时间效应的推论需要更加谨慎, 并且需要未来更多的实证证据, 才能形成一个整合的判断。

第四, 我们在考虑群体互动的过程中, 忽略了群体内部可能存在的层级划分。具体来说, 有些寝室内部可能有较为明显的非正式领导; 而有些寝室内部的所有成员则处于平等的关系。对于那些存在非正式领导的寝室而言, 非正式领导可能在组织寝室活动、协调成员关系、分配群体任务等方面都会发挥积极的作用, 在这种情况下存在非正式领导的寝室可能会比没有非正式领导的寝室表现出更强的群体凝聚力和更好的群体合作表现。此外, 当群体中存在非正式的领导时, 单纯采用平均分的方式来计算群体自我监控水平可能也忽略了非正式领导和普通成员对群体凝聚力和群体任务绩效的影响的差异, 未来研究可以采取更为精细的设计, 比如探究领导的个性特征和群体成员个性构成各自的作用和交互的作用(Colbert et al., 2014; LePine, Hollenbeck, Ilgen, & Hedlund, 1997)。

参考文献

Who attains social status? Effects of personality and physical attractiveness in social groups

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.116

URL

PMID:11474718

[本文引用: 1]

One of the most important goals and outcomes of social life is to attain status in the groups to which we belong. Such face-to-face status is defined by the amount of respect, influence, and prominence each member enjoys in the eyes of the others. Three studies investigated personological determinants of status in social groups (fraternity, sorority, and dormitory), relating the Big Five personality traits and physical attractiveness to peer ratings of status. High Extraversion substantially predicted elevated status for both sexes. High , incompatible with male gender norms, predicted lower status in men. None of the other Big Five traits predicted status. These effects were independent of attractiveness, which predicted higher status only in men. Contrary to previous claims, women's status ordering was just as stable as men's but emerged later. Discussion focuses on personological pathways to attaining status and on potential mediators.

Beyond dominance and competence: A moral virtue theory of status attainment

DOI:10.1177/1088868316649297

URL

PMID:27225037

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Recognition has grown that moral behavior (e.g., generosity) plays a role in status attainment, yet it remains unclear how, why, and when demonstrating moral characteristics enhances status. Drawing on philosophy, anthropology, psychology, and organizational behavior, I critically review a third route to attaining status: virtue, and propose a moral virtue theory of status attainment to provide a generalized account of the role of morality in status attainment. The moral virtue theory posits that acts of virtue elicit feelings of warmth and admiration (for virtue), and willing deference, toward the virtuous actor. I further consider how the scope and priority of moralities and virtues endorsed by a moral community are bound by culture and social class to affect which moral characteristics enhance status. I end by outlining an agenda for future research into the role of virtue in status attainment.

The social fabric of a team-based M.B.A. program: Network effects on student satisfaction and performance

Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations

DOI:10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.989

URL

PMID:14640811

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Previous meta-analytic examinations of group cohesion and performance have focused primarily on contextual factors. This study examined issues relevant to applied researchers by providing a more detailed analysis of the criterion domain. In addition, the authors reinvestigated the role of components of cohesion using more modern meta-analytic methods and in light of different types of performance criteria. The results of the authors' meta-analyses revealed stronger correlations between cohesion and performance when performance was defined as behavior (as opposed to outcome), when it was assessed with efficiency measures (as opposed to effectiveness measures), and as patterns of team workflow became more intensive. In addition, and in contrast to B. Mullen and C. Copper's (1994) meta-analysis, the 3 main components of cohesion were independently related to the various performance domains. Implications for organizations and future research on cohesion and performance are discussed. ((c) 2003 APA, all rights reserved)

Deep-level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis

DOI:10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.595

URL

PMID:17484544

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract This study sought to unify the team composition literature by using meta-analytic techniques to estimate the relationships between specified deep-level team composition variables (i.e., personality factors, values, abilities) and team performance. The strength of the team composition variable and team performance relationships was moderated by the study setting (lab or field) and the operationalization of the team composition variable. In lab settings, team minimum and maximum general mental ability and team mean emotional intelligence were related to team performance. Only negligible effects were observed in lab settings for the personality factor and team performance relationships, as well as the value and team performance relationships. In contrast, team minimum agreeableness and team mean conscientiousness, openness to experience, collectivism, and preference for teamwork emerged as strong predictors of team performance in field studies. Results can be used to effectively compose teams in organizations and guide future team composition research. 2007 APA, all rights reserved

The cost of status enhancement: Performance effects of individuals’ status mobility in task groups

DOI:10.1287/orsc.1100.0543 URL [本文引用: 1]

Ready to rumble: How team personality composition and task conflict interact to improve performance

DOI:10.1037/a0029845 URL [本文引用: 1]

Personality and leadership composition in top management teams: Implications for organizational effectiveness

DOI:10.1111/peps.2014.67.issue-2 URL [本文引用: 2]

Expectation states theory

Self-monitors in conversation: What do they monitor?

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.39.2.278

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Two experiments were conducted in which same-sex pairs of subjects who were either similar or opposite in self-monitoring conversed for 10 minutes. Conversations were videotaped, and the patterning of speech and gaze was examined. (Author/SS)

Self-monitoring personality at work: A meta- analytic investigation of construct validity

DOI:10.1037//0021-9010.87.2.390

URL

PMID:12002965

[本文引用: 1]

The validity of self-monitoring personality in organizational settings was examined. Meta-analyses were conducted (136 samples; total N = 23,191) investigating the relationship between self-monitoring personality and work-related variables, as well as the reliability of various self-monitoring measures. Results suggest that self-monitoring has relevance for understanding many organizational concerns, including job performance and leadership emergence. Sample-weighted mean differences favoring male respondents were also noted, suggesting that the sex-related effects for self-monitoring may partially explain noted disparities between men and women at higher organizational levels (i.e., the glass ceiling). Theory building and additional research are needed to better understand the construct-related inferences about self-monitoring personality, especially in terms of the performance, leadership, and attitudes of those at top organizational levels.

Do smarter teams do better? A meta-analysis of team level cognitive ability and team performance.

The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies

DOI:10.1016/j.jvb.2004.02.001

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This investigation had two purposes. The first was to determine whether the display of naturally felt emotions is distinct from surface acting and deep acting as a method of displaying organizationally desired emotions. The second purpose was to examine dispositional and situational antecedents of surface acting, deep acting, and the expression of naturally felt emotions. Results supported a three-dimensional structure separating deep acting, surface acting, and the expression of naturally felt emotions. In addition, the dispositional and situational variables exhibited theoretically consistent and distinct patterns of relationships with the three emotional labor strategies. Overall, the results of this study expand the nomological network of surface acting and deep acting and suggest that the expression of naturally felt emotions is a distinct strategy for displaying emotions at work and should be included in research on emotional labor.

The cohesion-performance relationship in sport: A 10-year retrospective meta-analysis

DOI:10.1007/s11332-014-0188-7 URL [本文引用: 1]

Helping one’s way to the top: Self-monitors achieve status by helping others and knowing who helps whom

DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1123 URL [本文引用: 1]

What good are positive emotions?

DOI:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300

URL

PMID:3156001

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract This article opens by noting that positive emotions do not fit existing models of emotions. Consequently, a new model is advanced to describe the form and function of a subset of positive emotions, including joy, interest, contentment, and love. This new model posits that these positive emotions serve to broaden an individual's momentary thought-action repertoire, which in turn has the effect of building that individual's physical, intellectual, and social resources. Empirical evidence to support this broaden-and-build model of positive emotions is reviewed, and implications for emotion regulation and health promotion are discussed.

Scholastic assessment or g? The relationship between the scholastic assessment test and general cognitive ability

Varieties of affect: Emotions and episodes, moods, and sentiments. In Ekman, P., & Davidson, R. J. (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 59-67)

Self-monitoring: Appraisal and reappraisal

Sex, task, and behavioral flexibility effects on leadership perceptions

Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress

Self-monitoring in social interaction: The centrality of self-Affect

Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement

The dynamic nature of conflict: A longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance

Self-monitoring and turnover - the impact of personality on intent to leave

Mood and emotions in small groups and work teams

Two investigations of the relationships among group goals, goal commitment, cohesion, and performance

How do they get there? An examination of the antecedents of centrality in team networks

Answers to 20 Questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement

Revision of the self-monitoring scale

Team adaptation and postchange performance: Effects of team composition in terms of members’ cognitive ability and personality

Effects of individual differences on the performance of hierarchical decision-making teams: Much more than g

CEO-TMT exchange, TMT personality composition, and decision quality: The mediating role of TMT psychological empowerment

Process of interaction among members in simulated work teams

模拟情境中工作团队成员互动过程的初步研究及其测量

Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN

Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods

Social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status

The effects of job complexity and autonomy on cohesiveness in collectivistic and individualistic work groups: A cross-cultural analysis

The social networks of high and low self-monitors: Implications for workplace performance

The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration

Self-monitoring, trust, and commitment in romantic relationships

The ripple effect of personality on social structure: Self-monitoring origins of network brokerage

Holding your place: Reactions to the prospect of status gains and losses

Justice in self-monitoring teams: The role of social networks in the emergence of procedural justice climates

Chameleonic or consistent? A multilevel investigation of emotional labor variability and self-monitoring

Justice as a dependent variable: subordinate charisma as a predictor of interpersonal and informational justice perceptions

Self-monitoring of expressive behavior

Thinking about ourselves and others: Self-monitoring and social knowledge

RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals

Developmental sequence in small groups

Self-monitoring and humor production

Achieving desired images while avoiding undesired image: Exploring the role of self-monitoring in impression management

Effects of crew composition on crew performance: Does the whole equal the sum of its parts?

Managing personal networks: An examination of how high self-monitors achieve better job performance

The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, expanded form

Self-monitoring and trait-based variance in leadership: An investigation of leader flexibility across multiple group situations