1 引言

情绪感染是指感官情绪信息自动化地、无意识地在人际间传递的过程(张奇勇, 卢家楣, 2013), 情绪觉察者的模仿-反馈机制影响了觉察者的情绪体验, 导致觉察者产生了可觉察的情绪, 由此觉察者感染上了他所觉察的情绪。这一过程可表示如下:觉察-模仿-反馈-情绪(Falkenberg, Bartels, & Wild, 2008)。张奇勇等对情绪感染的概念与发生机制作了详细论述, 并从理论与实证上论证了这一机制的科学性(张奇勇, 卢家楣, 2013; 张奇勇, 卢家楣, 闫志英, 陈成辉, 2016)。依据情绪感染的人际关系理论, 情绪感染受人际关系因素的影响, 人际影响因素如团结性、人际信任水平和人际态度对情绪感染的影响说明情绪感染是一个人际现象(Vijayalakshmi & Bhattacharyya, 2012), 而群体的团结性、信任水平、态度是群体成员对群体以及其他成员的评价, 属于认知领域, 这说明认知对情绪感染具有调节作用, 又如先入观念对情绪感染的调节(张奇勇, 卢家楣, 2015)。又有研究表明, 评价决定了情绪反应和感受的本质(Urry, 2009), 对人际的团结性、人际信任水平和人际态度的评价均带有一定的情感倾向性, 可能是这种“先入情感”决定了对方情绪对我的感染力。例如, 一些研究者们已证实积极的政治态度可以提高一个人看到政治领导(看起来像)时的积极脸部表情的EMG水平(Tee, 2015), 这一心理过程可描述如下:觉察者在无意识层面上自动化地提取了与被觉察者的情感关系从而唤醒了相应的情绪体验, 觉察者的情绪体验决定了对方的情绪感染的水平和方向, 由于这一情绪体验先于情绪感染而发生, 所以称之为情绪感染的前情绪。如果这一推理成立的话, 那么觉察者的前情绪是可以调节他人情绪对觉察者的感染水平的。觉察者的前情绪对情绪感染的调节作用可能存在两个方向:反向调节与正向助长。

依据消极情绪的指向对象不同, 笔者初步将消极情绪分为攻击性的和消沉性的。攻击性的消极情绪如仇恨、愤怒、轻蔑、敌意等, 具有攻击他人的心理倾向性或动机, 攻击性消极情绪具有“对象指向明确”和“希望打击对方”的心理特点, 所以在情绪体验上易与对方的情绪极性相反, 易产生反向情绪感染, 所以在反向情绪感染实验中选择了“仇恨”作为前情绪; 消沉性的消极情绪如烦躁、悲伤、恐惧、绝望等, 具有“对象指向不明确”或“无法打击对方”的特点, 所以不具有明确的攻击性动机。个体在体验消沉性消极情绪时, 极想摆脱自己的当前情绪状态, 所以更容易接受积极的情绪感染, 降阈情绪感染就会发生, 本研究的消沉性消极前情绪以烦躁为例。

攻击性消极前情绪对情绪感染的反向调节:反向情绪感染是由于觉察者前情绪的存在使其体验到了与被觉察者相反的情绪。例如, 现实生活中也有这样一种体验, 如看到一个自己厌恶的人与他的朋友说笑时, 有可能会激发出我们更讨厌的情绪体验, 而不会被他人的喜悦情绪所感染。这一心理现象可以用于解释为什么在一个团结、信任水平高的群体中, 群体成员间的相互情绪感染就大, 而在一个涣散的群体中, 群体间的情绪感染就小(Torrente, Salanova, & Llorens, 2013), 甚至在敌对的人际间还会出现幸灾乐祸的心理现象, 即觉察到仇视对象的消极情绪反而会让觉察者体验到快乐情绪, 这一心理现象我们称之为“反向情绪感染”。反向情绪感染说明, 情绪感染可以受到觉察者的前情绪的反向调节。

消沉性消极前情绪对情绪感染的降阈调节:觉察者的消极前情绪也可能正向助长他人的积极情绪感染力。关于前情绪对情绪感染的助长作用, 以往研究已有所涉及, 但往往研究的是“前情绪与情绪感染中的情绪在极性上是相同的”, 如前所述, 积极的政治态度可以提高一个人看到政治领导时的积极脸部表情, 那么有没有一种可能, 前情绪与情绪感染中的情绪在极性上是相反的, 并且前情绪能够助长情绪感染, 如觉察者的前情绪是烦躁(消极的情绪), 却更易感染他人的快乐情绪(积极的情绪)。

心境一致性理论告诉我们, 心境一致性偏向可以影响个体对相匹配情绪的注意力(Bhullar, 2012), 如果心境是积极的, 那么人们就更容易受积极情绪的影响, 如果心境是消极的, 那么人们就更容易受消极情绪的影响(Knott & Thorley, 2014), 这种一致性心理倾向不光在情绪中发现, 在学习、记忆、注意力中均有所发现, 如Connelly等人发现当人处于正性情绪时倾向于将领导察觉为更有魅力, 处于负性情绪的人更倾向于认为领导没有魅力(Connelly & Gooty, 2015)。以心境一致性理论进行推理的话, 当觉察者的前情绪是消极的, 那么他就更易感染他人的消极情绪, 反之亦然, 但是事实是不是总是这样的呢?著名的“斯德哥尔摩综合征”是指受害者对于犯罪者产生好感、依赖心, 被害人在整个情感变化过程中可能经历了以下阶段:愤怒-恐惧-绝望-喜爱。这是一种典型的反向情绪心理, 所谓反向情绪心理是指个体前后出现两种极性相反的情绪体验, 并且前情绪体验会放大后情绪体验的深刻性。如消极的前情绪体验会助长后继的积极情绪体验, 这与心境一致性理论严重相悖。反向情绪心理能否在情绪感染中发生, 如果能发生, 其发生的机制如何?情绪感染中的反向情绪心理暂被称为“降阈情绪感染”。

有大量的研究表明, 情绪会影响认知评价, 使评价与情绪趋于一致。同样, 如果消极的前情绪对情绪感染具有反向调节和降阈调节作用, 那么势必也会影响对事件的后续认知评价, 这是因为人们倾向于对当前事物做出与当前情绪相一致的评价(Zebrowitz, Boshyan, Ward, Gutchess, & Hadjikhani, 2017)。反过来, 也可以通过觉察者的评价来投射出他当时的情绪状态, 进一步验证情绪感染的调节现象有没有发生。

基于上述推理, 对研究作如下假设:

H1:在反向情绪感染中, 被试的消极前情绪可以阻断对方的积极情绪(后情绪)感染, 对方的积极后情绪不但没有感染被试, 反而加剧了被试的消极的前情绪体验, 积极情绪感染朝着更消极的方向发展。由此, 被试会加固甚至放大对对方的原有评价, 如原来前情绪为仇恨, 反向情绪感染发生后可能会加剧仇恨, 从而倾向于对对方更消极的评价。

H2:在降阈情绪感染中, 被试的消极前情绪可以助长对方的积极情绪(后情绪)感染力, 被试将摆脱原有的消极前情绪体验, 对对方的积极情绪感染表现出更大的易感性。由此, 被试将会随着原有消极前情绪的消失和积极情绪的产生而改变自己对事件的评价态度, 如原来前情绪为烦躁, 降阈情绪感染发生后更倾向于对事件做出更积极的评价。

2 研究1:反向情绪感染

2.1 研究目的

证明被试的仇恨前情绪体验对他人的积极情绪感染具有反向调节作用, 反向调节的结果是不但阻止了他人的积极情绪感染, 并且使被试体验到了更深刻的仇恨情绪。

2.2 研究方法

2.2.1 被试

以公开招募的方式选取来自扬州大学的非心理学或教育专业背景的大学生50名, 所有被试视觉正常或矫正后正常, 听觉均正常, 无精神类疾病史。其中有4名被试数据记录缺损而被剔除。最后获得有效被试数据46名, 年龄在18~22岁之间, 其中男生23名, 女生23名。

2.2.2 实验材料

选取南京大屠杀片段, 一段为中央电视台批露的《南京暴行纪实》(约翰·马吉)视频, 时长为30分钟, 另一段为剪辑后的《南京大屠杀纪录片》约5分钟, 视频分辨率:720×576, 选取两段黄种人生活搞笑有声视频(没有对白), 每个视频时长各5分钟。对两个搞笑视频的搞笑程度进行评定, 采用7级(0~7)评分, 分数越高表示越搞笑, 视频1与视频2的平均数与标准差分别为:4.13 ± 1.34和4.46 ± 1.41, 统计结果显示t(55) = -1.73, p = 0.09 > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.25, 1 - β = 0.41, 没有显著性差异。

2.2.3 实验工具

本研究的实验仪器采用加拿大Thought Technology公司生产的BioNeuro八通道电脑生物反馈仪, 型号为BioNeuro INFINITI SA7900C, 数据采集系统软件为MULTIMEDIA BIOFEEDBACK SOFTWARE (version 5.2.4)。本研究使用了A、B、D、G四个通道, 设定A通道为MyoScan-Pro400, 用于监测左脸颊肌电(采集脸颊EMG, 单位为µV); 设定B通道为EEG-Z, 用于监测脑电(采集α波、SMR和β波, 中央顶区Cz点); 设定D通道为SC- Pro/Flex, 用于监测皮电(利手食指、无名指指腹) (采集皮电SC, 单位为mho); 设定G通道为HR/BVP-Pro/Flex, 用于测定血容量(利手中指指腹) (采集BVP幅度; BVP频率, 单位为次/min)。

2.2.4 实验程序

实验前一天组织被试一起看《南京暴行纪实》视频, 并进行一个简短的讨论, 以唤醒被试一致的情绪——仇恨, 以便第二天再组织被试观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》时, 能快速唤醒被试的仇恨情绪体验。第二天实验开始, 主试向被试介绍实验相关的情况与注意事项, 并签订《实验知情协议书》。实验准备就绪后, 先播放音乐并指导被试做放松训练(6 min), 之后测试被试生理指标的基线水平(300 s)。接下来先让被试观看另一段《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频, 并测量被试的生理指标, 观看结束后有一个主观情绪评定(-7~7), 之后, 安排被试在仿真课堂教学情境下观看两段生活搞笑视频并测量被试的生理指标, 两段视频的播放次序在被试内平衡。在播放每一段视频前均有指导语:现在给你播放一段来自日本/中国的生活搞笑视频, 请你认真观看, 并对视频中的每一个笑点等级进行评定。视频的笑点等级评定采用7级(1~7)评分, 分数越高表示越搞笑。

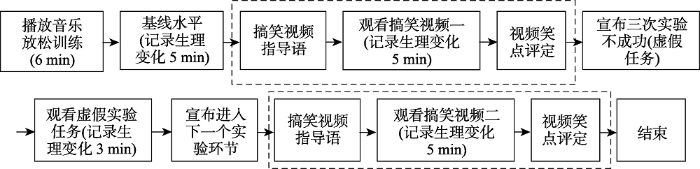

实验采用被试内设计, 所有被试都要经过图1所示的流程处理。

图1

2.3 结果分析

2.3.1 “日本”搞笑视频的情绪感染力检验

将学生观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频(条件Ⅱ)、“日本”搞笑视频(条件Ⅲ)时的生理指标与基线(条件Ⅰ)的生理指标进行比较。

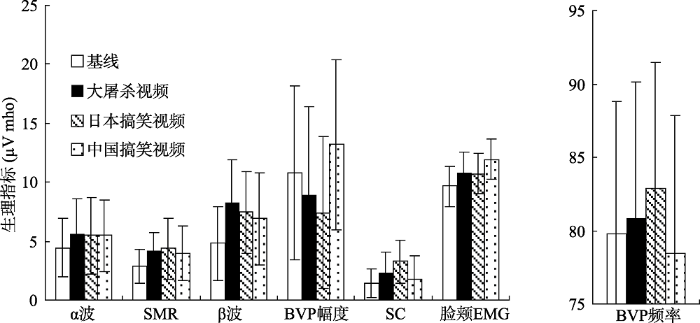

采用重复测量设计的方差(repeated measures ANOVA)分析对三种实验条件下被试的7个生理指标进行分析, 结果显示, 实验条件主效应显著, F(14,32) = 31.15, p < 0.001, Partial η2 = 0.93, 1 - β = 1。描述性统计结果如图2所示。

图2

一元方差分析(univariate tests)可以检验每个生理指标在三种实验条件下是否达到显著性水平, 结果如表1所示。

表1 7个生理指标的一元方差分析结果

| 生理指标 | F | p | Partial η2 | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α波 | 4.48* | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.65 |

| SMR | 17.96** | 0.00 | 0.29 | 1.00 |

| β波 | 58.97** | 0.00 | 0.57 | 1.00 |

| BVP幅度 | 36.93** | 0.00 | 0.45 | 1.00 |

| BVP频率 | 11.01** | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.94 |

| SC | 27.09** | 0.00 | 0.38 | 1.00 |

| 脸颊EMG | 13.02** | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.97 |

注:*表示p < 0.05, **表示p < 0.01, 下同。

由表1可见, 7个生理指标中一元方差检验均达到显著水平, 其中α波的统计检验力不高(1 - β = 0.65), 其多重比较的结果可作为参考。

从表2可以看出, 观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频(条件Ⅱ)与基线(条件Ⅰ)相比较, 在任何生理指标上均存在极其显著性差异(p < 0.001), 其中BVP幅度、BVP频率与SC的指标变化足以说明观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》成功诱发了学生的消极情绪(观后询问证明是“仇恨”情绪)。观看“日本”搞笑视频(条件Ⅲ)与基线(条件Ⅰ)相比较, 除α波外, 其他6项生理指标均存在极其显著性差异(p < 0.001), 而且变化趋势与观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频时相同, 说明“日本”搞笑视频并没有成功诱发学生积极的情绪体验。观看“日本”搞笑视频(条件Ⅲ)与观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频(条件Ⅱ)相比较, 在BVP幅度上有极其显著下降(p < 0.001), BVP幅度反映了血管的舒张程度, 如当同情被唤起时就会改变, 当压力或有意识努力时, 就会有BVP下降(Hirvikoski et al., 2011), 显然中国被试在观看“日本”搞笑视频时感觉到了压力, 足以说明, 观看“日本”搞笑视频不但没有诱发学生快乐的情绪体验, 反而加剧了学生的愤怒情绪体验, 出现了反向情绪感染。

表2 7个生理指标在三种实验条件下多重比较的结果

| 生理指标 | Ⅱ-Ⅰ | Ⅲ-Ⅰ | Ⅲ-Ⅱ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | p | MD | p | MD | p | |

| α波 | 1.14** | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.05 | -0.12 | 0.79 |

| SMR | 1.32** | 0.00 | 1.51** | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.56 |

| β波 | 3.51** | 0.00 | 2.67** | 0.00 | -0.85* | 0.04 |

| BVP幅度 | -1.82** | 0.00 | -3.37** | 0.00 | -1.55** | 0.00 |

| BVP频率 | 1.08** | 0.00 | 3.10** | 0.00 | 2.01* | 0.02 |

| SC | 0.88** | 0.00 | 1.83** | 0.00 | 0.95** | 0.00 |

| 脸颊EMG | 1.19** | 0.00 | 1.08** | 0.00 | -0.11 | 0.72 |

对“笑点”的主观评定进行配对样本t检验, 结果表明, 观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频与观看“日本”搞笑视频在主观评定上没有显著差别, M ± SD分别为:-6.50 ± 0.59, -6.67 ± 0.56, t(45) = -1.66, p = 0.10 > 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.29, 1 - β = 0.38, 情绪评定出现地板效应(并非任务难度所诱发)。

2.3.2 “中国”搞笑视频的情绪感染力检验

将学生观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频(条件Ⅱ)、“中国”搞笑视频(条件Ⅳ)时的生理指标与基线(条件Ⅰ)的生理指标进行比较。

表3 7个生理指标的一元方差分析结果

| 生理指标 | F | p | Partial η2 | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α波 | 8.36** | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.93 |

| SMR | 14.93** | 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.99 |

| β波 | 43.52** | 0.00 | 0.49 | 1.00 |

| BVP幅度 | 91.29** | 0.00 | 0.67 | 1.00 |

| BVP频率 | 22.55** | 0.00 | 0.33 | 1.00 |

| SC | 4.74* | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.71 |

| 脸颊EMG | 43.36** | 0.00 | 0.49 | 1.00 |

表4是7个生理指标在三种实验条件下多重比较的结果, 其中实验条件Ⅱ与条件Ⅰ的比较结果与上述相同, 兹不赘述。观看“中国”搞笑视频(条件Ⅳ)与基线(条件Ⅰ)相比较, α波、SMR、β波均有极其显著的提高(p < 0.001), 这是注意力的指标, BVP幅度有极其显著上升(p < 0.001), BVP频率有极其显著下降(p < 0.001), 这两个指标的变化方向与诱发“仇恨”情绪时的生理指标变化方向相反, 可以认为“中国”搞笑视频成功诱发了学生的积极情绪体验, 这一结果可以从脸颊肌电的变化上得到进一步验证, 在脸颊肌电上有显著提高(p < 0.05)。观看“中国”搞笑视频(条件Ⅳ)与观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频(条件Ⅱ)相比较, 在BVP幅度、脸颊肌电上有极其显著上升(p < 0.001), 而在BVP频率上有极其显著下降(p < 0.001), 即“中国”搞笑视频成功诱发了学生快乐的情绪体验。

表4 7个生理指标在三种实验条件下多重比较的结果

| 生理指标 | Ⅱ-Ⅰ | Ⅳ-Ⅰ | Ⅳ-Ⅱ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | p | MD | p | MD | p | |

| α波 | 1.14** | 0.00 | 1.01** | 0.00 | -0.12 | 0.74 |

| SMR | 1.32** | 0.00 | 1.08** | 0.00 | -0.24 | 0.46 |

| β波 | 3.51** | 0.00 | 2.11** | 0.00 | -1.41** | 0.01 |

| BVP幅度 | -1.82** | 0.00 | 2.38** | 0.00 | 4.20** | 0.00 |

| BVP频率 | 1.08** | 0.00 | -1.30** | 0.00 | -2.38** | 0.00 |

| SC | 0.88** | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.24 | -0.55 | 0.13 |

| 脸颊EMG | 1.19** | 0.00 | 2.28* | 0.04 | 1.09** | 0.00 |

对“笑点”的主观评定进行配对样本t检验, 结果表明, 观看“中国”搞笑视频较“日本”搞笑视频在主观评定上有极其显著性差异, M ± SD分别为:3.98 ± 1.27, -6.67 ± 0.56, t(45) = 48.36, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 10.85, 1 - β = 1, 有极其显著性差异。

2.4 讨论

上述研究结果表明学生观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频(条件Ⅱ)与基线(条件Ⅰ)相比较, 成功诱发了学生的消极情绪。与基线相比, 观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频时BVP幅度显著下降, 而BVP频率上升, 通过观后对学生进一步询问表明是“愤怒”情绪。BVP幅度与主观快乐体验之间存在显著相关(Lai, Li, & Lee, 2012), 如厌恶的声音刺激(消极刺激)会导致BVP幅度下降(Ooishi & Kashino, 2012), 由于共情而叹息(消极情绪)时BVP容量也会下降(Peper, Harvey, Lin, Tyiova, & Moss, 2007), 相反个体体验到的痛苦情绪越少(积极情绪越多), BVP就越高, 心率也就越低(Park, Lee, Sohn, Eom, & Sohn, 2014)。Fink等也使用观看视频的方法研究儿童的悲伤移情和兴趣忧虑(interest-worry)移情, 研究表明在心率上有显著性差异(Fink, Heathers, & de Rosnay, 2015)。由于这些指标与情绪的生理唤醒之间的密切关系, 因此可以反映被试对情绪刺激的生理反馈水平。与基线相比, 观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频时SC与脸颊EMG显著上升, 皮电指标通常被用于测量被试的愉悦情绪或者焦虑情绪反应(Gouizi, Reguig, & Maaoui, 2011; Balconi & Canavesio, 2013), 焦虑情绪会提升SC水平, 仇恨也属于消极情绪, 所以SC也会上升。肌电直接与情绪信息的自动化加工相关, 而不受意识控制(Magnée, de Gelder, van Engeland, & Kemner, 2007), 人在高兴情境下就会提升脸颊EMG水平, 从而体验到快乐情绪(Dimberg, Andréasson, & Thunberg, 2011; Balconi & Canavesio, 2013)。Balconi等研究了在合作情境下能提高颧骨肌肌电与正性积极情绪, 在冲突或不合作的情境下能提高皱眉肌肌电, 并有更高的皮电和心率(Balconi & Bortolotti, 2012)。这是因为快乐情绪通常有笑的表情或微表情, 这样会拉动脸部肌肉动作, 从而提升了脸颊肌电水平(Dimberg & Thunberg, 2012), 而本研究在愤怒情绪下检测到脸颊肌电水平提升, 这可能与愤怒情绪通常会有“咬牙切齿”的微表情有关, 这同样会拉动脸部肌肉动作, 提高脸颊肌电水平。

将观看“日本”搞笑视频与基线相比较, 在生理指标上的变化趋势与观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频时相同, 由此证明“日本”搞笑视频并没有成功诱发学生积极的情绪体验。将观看“日本”搞笑视频与观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频相比较, 生理指标的变化方向不仅相同, 而且唤醒程度加大, 进一步证明观看“日本”搞笑视频反而加剧了学生的愤怒情绪体验, 出现了反向情绪感染。

3 研究2:降阈情绪感染

3.1 研究目的

证明被试的烦躁前情绪可以助长他人的快乐情绪对被试的感染力, 与没有体验过烦躁情绪前相比, 体验过烦躁情绪后的被试对他人的积极情绪更具易感性。

3.2 研究方法

3.2.1 被试

以公开招募的方式选取来自扬州大学的非心理学或教育专业背景的大学生53名, 年龄在18~22岁之间, 所有被试视觉正常或矫正后正常, 听觉均正常, 其中有3名被试数据记录缺损而被剔除。最后获得有效被试数据46名, 年龄在18~22岁之间, 其中男、女生各25名。

3.2.2 实验材料

选取两段黄种人生活搞笑有声视频, 同研究1。

3.2.3 实验工具

实验工具与采集通道设置同研究1。

3.2.4 实验程序

实验流程如下:被试首先在实验员的指导下做6分钟的音乐放松训练, 之后测量被试的基线生理水平(300 s)。接下来给被试播放观看视频的指导语:现在给你播放一段生活搞笑视频, 请你认真观看, 并对视频中的每一个笑点等级进行评定。两个搞笑视频的播放顺序在被试间平衡, 视频的笑点等级评定采用7级(1~7)评分(模块一)。之后, 有一个虚假的实验任务, 任务重复三次, 每次都告知被试实验不成功, 目的是为了诱发被试烦躁的前情绪体验, 为了检验烦躁情绪是否诱发成功, 有一个观看虚假实验任务的视频(180 s), 观看虚假任务是为了唤起被试对虚假任务的情绪记忆, 并记录被试的生理指标。虚假任务结束后, 不向被试做任何解释, 向被试宣布进入实验的最后一个环节——再观看一段生活搞笑视频, 实验流程同样从指导语开始至笑点评定结束(模块二)。实验流程如图3所示。

图3

实验采用被试内设计, 所有被试都要经过图3所示的流程处理。

3.3 结果分析

3.3.1 正负情绪的生理指标比较

将学生观看搞笑视频一(条件Ⅱ)、虚假任务视频(条件Ⅲ)时的生理指标与基线(条件Ⅰ)的生理指标进行比较。

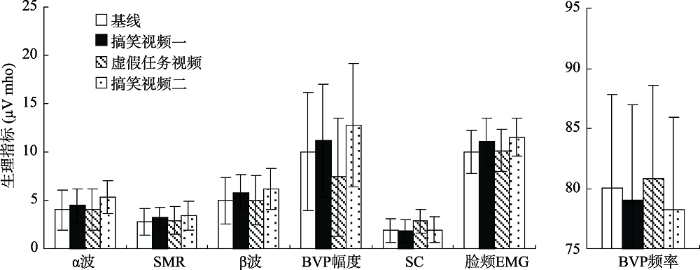

采用重复测量设计的方差分析对三种实验条件下被试的7个生理指标进行分析, 结果显示, 实验条件主效应显著, F (14,36) = 27.84, p < 0.001, Partial η2 = 0.92, 1 - β = 1。描述性统计结果如图4所示。

图4

一元方差分析用于检验每个生理指标在三种实验条件下是否达到显著性水平。

如表5所示, 7个生理指标中一元方差检验均达到显著水平, 且均有很高的统计检验力。

表5 7个生理指标的一元方差分析结果

| 生理指标 | F | p | Partial η2 | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α波 | 9.75** | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.95 |

| SMR | 6.59** | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.82 |

| β波 | 17.32** | 0.00 | 0.26 | 1.00 |

| BVP幅度 | 88.74** | 0.00 | 0.64 | 1.00 |

| BVP频率 | 26.37** | 0.00 | 0.35 | 1.00 |

| SC | 95.25** | 0.00 | 0.66 | 1.00 |

| 脸颊EMG | 24.70** | 0.00 | 0.34 | 1.00 |

从表6中可以看出, 观看搞笑视频一(条件Ⅱ)与基线(条件Ⅰ)相比较, 除了SC外, 在其他生理指标上均存在极其显著性差异(p < 0.001), 其中BVP幅度、BVP频率与脸颊EMG的指标变化足以说明观看搞笑视频一成功诱发了学生的快乐情绪。观看虚假任务视频(条件Ⅲ)与基线(条件Ⅰ)相比较, 在BVP幅度、BVP频率、SC上均存在极其显著性差异(p < 0.001), 而且变化趋势与观看搞笑视频一时相反, 说明学生观看虚假任务视频时所诱发的情绪与观看搞笑视频时所诱发的情绪是相反的, 事后询问, 学生在经历三次不成功体验后, 普遍体验到了烦躁的情绪。观看虚假任务视频(条件Ⅲ)与观看搞笑视频一(条件Ⅱ)相比较, 在BVP幅度上有极其显著下降(p < 0.001), BVP幅度下降能较好地反映出焦虑或紧张等消极情绪(Park, Lee, Sohn, Eom, & Sohn, 2014)。

表6 7个生理指标在三种实验条件下多重比较的结果

| 生理指标 | Ⅱ-Ⅰ | Ⅲ-Ⅰ | Ⅲ-Ⅱ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | p | MD | p | MD | p | |

| α波 | 0.43** | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.86 | -0.42** | 0.01 |

| SMR | 0.43** | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.17 | -0.32* | 0.04 |

| β波 | 0.80** | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.79 | -0.77** | 0.04 |

| BVP幅度 | 1.14** | 0.00 | -1.13** | 0.00 | -2.27** | 0.00 |

| BVP频率 | -0.99** | 0.00 | 0.77** | 0.01 | 1.76** | 0.00 |

| SC | -0.04 | 0.42 | 0.97** | 0.00 | 1.02** | 0.00 |

| 脸颊EMG | 1.07** | 0.00 | 0.15 | 0.09 | -0.92** | 0.00 |

3.3.2 消极前情绪对积极情绪感染力的调节

将学生观看搞笑视频一(条件Ⅱ)、搞笑视频二(条件Ⅳ)时的生理指标与基线(条件Ⅰ)的生理指标进行比较。

表7 7个生理指标的一元方差分析结果

| 生理指标 | F | p | Partial η2 | Observed Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α波 | 42.65** | 0.00 | 0.47 | 1.00 |

| SMR | 9.74** | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.97 |

| β波 | 25.77** | 0.00 | 0.35 | 1.00 |

| BVP幅度 | 103.82** | 0.00 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| BVP频率 | 43.18** | 0.00 | 0.47 | 1.00 |

| SC | 1.71 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.34 |

| 脸颊EMG | 32.51** | 0.00 | 0.40 | 1.00 |

表8是7个生理指标在三种实验条件下多重比较的结果, 其中实验条件Ⅱ与条件Ⅰ的比较结果与上述相同, 兹不赘述。观看搞笑视频二(条件Ⅳ)与基线(条件Ⅰ)相比较, α波、SMR、β波均有极其显著的提高(p < 0.001), 这是注意力的指标, BVP幅度有极其显著上升(p < 0.001), BVP频率有极其显著下降(p < 0.001), 这两个指标的变化方向与诱发快乐情绪时的生理指标变化方向相同, 可以认为搞笑视频二同样诱发了学生的积极情绪体验, 这一结果可以从脸颊肌电的变化上得到进一步验证, 在脸颊肌电上也有极其显著提高(p < 0.001)。观看搞笑视频二(条件Ⅳ)与观看搞笑视频一(条件Ⅱ)相比较, 在BVP幅度、脸颊肌电上有显著上升(p < 0.001, p < 0.05), 而在BVP频率上有极其显著下降(p < 0.001), 生理指标的变化方向与实验条件“Ⅱ-Ⅰ”相同, 说明实验条件Ⅳ与实验条件Ⅱ相比, 在程度上诱发出学生更快乐的情绪体验。

表8 7个生理指标在三种实验条件下多重比较的结果

| 生理指标 | Ⅱ-Ⅰ | Ⅳ-Ⅰ | Ⅳ-Ⅱ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | p | MD | p | MD | p | |

| α波 | 0.43** | 0.00 | 1.33** | 0.00 | 0.90** | 0.00 |

| SMR | 0.43** | 0.00 | 0.65** | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| β波 | 0.80** | 0.00 | 1.18** | 0.00 | 0.38* | 0.03 |

| BVP幅度 | 1.14** | 0.00 | 2.75** | 0.00 | 1.61** | 0.00 |

| BVP频率 | -0.99** | 0.00 | -1.76** | 0.00 | -0.77** | 0.00 |

| SC | -0.04 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| 脸颊EMG | 1.07** | 0.00 | 1.53** | 0.00 | 0.46* | 0.03 |

对“笑点”的主观评定进行配对样本t检验, 结果表明, 观看搞笑视频二比搞笑视频一在主观评定上有极其显著性差异, M ± SD分别为:4.02 ± 1.27, 3.40 ± 1.03, t(49) = 6.29, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.54, 1 - β = 1.00, 视频二的笑点等级显著高于视频一。

3.4 讨论

在降阈情绪感染实验中, 观看搞笑视频一成功诱发了学生快乐的情绪体验, 三次失败的虚假实验成功地诱发了被试消极的情绪体验, 事后询问被试, 被试均认为失败让他们体验到了不同程度的“烦躁”。有研究表明, BVP是反映情绪唤醒程度的敏感性生理指标, 人在被网络欺凌的情况下BVP幅度会下降(Caravita, Colombo, Stefanelli, & Zigliani, 2016)。与基线相比, 被试观看搞笑视频一与观看虚假任务视频时, BVP出现了反方向的变化, 可以基本确定诱发的是两种不同极性的情绪——积极的与消极的。

被试在观看搞笑视频二与观看搞笑视频一相比较, 在BVP幅度上有极其显著上升, 脸颊肌电上也有显著上升, 情绪也可以由脸部肌肉动作来激活, 这一理论被称为“面部反馈理论假设” (Dzokoto, Wallace, Peters, & Bentsi-Enchill, 2014), 人对兴奋的刺激则会有一个更大的脸颊EMG (Dimberg et al., 2011), 如看到高兴的表情, 脸嘴角就会翘起, 看到沮丧的表情, 脸嘴角就会下垂(Dezecache et al., 2013), 人们甚至接触到“皱眉”这个词语时就会激活相应的脸部肌肉动作(Cheshin, Rafaeli, & Bos, 2011)。面部反馈理论中的维度假设认为, 情绪归纳为效能、活动、退缩-接近三个维度, 其中活动体现了情绪的强度, 对于同一组被试来说, 面部反应的强度与自主系反应之间呈现正相关, 所以脸颊肌电上的强度差异反映了自主系反应的强度, 也就是说生理唤醒的强度, 表达了不同的情绪体验强度, 说明被试在观看搞笑视频二时体验到的积极情绪强度大于观看视频一时。通过事后被试对“笑点”的主观评定得到进一步的验证, 被试认为视频二的笑点等级显著高于视频一。由于被试在观看视频二之前经历了三次虚假实验的失败体验, 这从逻辑链上可以得出:是三次失败体验(烦躁情绪), 助长了被试对快乐情绪的易感性。

4 总讨论

4.1 反向情绪感染的“情绪-内驱力”解释模型

有学者研究了先入观念对情绪感染的调节, 实验中随机指定教师为“权威”教师或“新手”教师, 结果发现“权威”教师的积极情绪感染力高于“新手”教师, 而“新手”教师的消极情绪感染力(倦怠)比“权威”教师的消极情绪感染力更强(张奇勇, 卢家楣, 2015)。上述“权威”教师与“新手”教师只是一个概念, 这一概念会无意识启动一个刻板认知, 并对之后的情绪感染起调节作用。而本研究在观看《南京大屠杀纪录片》视频后, 告诉被试将观看一个“日本”搞笑视频, 启动的不光是“日本”这一个概念, 通过观看南京大屠杀的纪录片, 诱发出被试强烈的仇恨情绪体验, 这一情绪体验相对于“日本”搞笑视频而言属于情绪感染前的前情绪。先入观念对情绪感染的调节方式有两种:“专注”和“合理化”, 调节的结果也有两种:“易感性”与“免疫性” (张奇勇, 卢家楣, 2015)。而在反向情绪感染中, 攻击性消极前情绪对情绪感染的调节不仅仅是阻止情绪感染, 而是体验到了更深刻的消极前情绪, 正如你看到“仇人”在说笑, 他的情绪不仅对你没有感染力, 反而会让你体验到更强烈的仇视情绪。对于这一心理现象可作如下解释:“仇人”不仅仅是一个概念, 更是一个情绪符号, 当你第一眼看到他时就诱发了你的仇恨情绪体验, 因为当人们暴露在充满情绪内容的概念中时, 这样的概念可以激活人们的脸部肌肉动作以展示情绪(Ekman, 2009), 所以通过概念激活情绪的路径是可能的。汤姆金斯(Tomkins, S.)认为情绪具有动机作用, 内驱力在强度和紧迫性上, 作为动机是不够的, 感情上的感受必然附加到内驱力中, 并使内驱力得到加强。报复仇人的动机就产生于报复性的情感需要与仇人在场的诱因中, 这是缓解仇恨情绪的最好方法, 也就是说任何出于社会性考虑的克制行为(不是宽恕)不利于仇恨情绪的缓解, 充其量算作是仇恨的压抑, 更不用说看到仇人在说笑啦, 因为仇人的快乐情绪与报复性地惩罚仇人而让仇人痛苦的动机倾向是完全相反的, 任何与动机指向相悖的行为不但不能缓解内驱力, 反而会加剧内驱力的强度和紧迫性, 所以会唤醒更强烈的仇恨情感附加到内驱力之中, 从而强化了仇恨的前情绪体验, 由此就发生了反向情绪感染。本研究的H1假设, 反向情绪感染发生后被试可能会加固甚至放大对对方的原有评价, 如原来是仇恨情绪, 反向情绪感染发生后可能会加剧仇恨, 从而倾向于对对方更低的评价, 这种低评价也是宣泄仇恨情绪的方式之一, 与报复性的动机是一致的, 所不同的是, 一个是攻击性的, 一个是隐蔽性的。然而在实验中由于仇日情绪出现了“天花板效应”, 差异未能显现, 有待于调整实验方案去进一步证实。

4.2 降阈情绪感染的“动机-相对阈限”解释模型

在模块二中被试经历了三次不成功的消极体验, 情绪烦躁, 如前所述, 个体在体验消沉性消极情绪时, 个体具有摆脱自己的当前情绪状态的动机和愿望(如, 我不想再做这个实验了), 而观看搞笑视频与个体当前的动机状态相一致, 消极的前情绪降低了被试对积极的后情绪的感受阈限, 使得被试对后情绪的感受性加强, 从而放大了积极的后情绪体验, 这就是之所以称为“降阈调节”的心理机制。正如斯德哥尔摩综合征中, 绑匪在受害者绝望时施以小恩小惠, 个体为了保护自身避免遭受更大的伤害, 有亲近绑匪或摆脱“绝望”的主观动机, “绝望”降低了对“礼遇”的感知阈限, 受害者对绑匪的积极情绪表现出易感性, 这与受害者的“想亲近绑匪”和摆脱“绝望”的动机是相一致的, 所以更易对绑匪产生喜爱情感, 甚至这种好评要远远好于平时相同的礼遇所带来的情感体验。当然, 斯德哥尔摩综合征还有认知调节的心理过程存在, 但是“降阈”的心理现象依然存在。

通过上述分析, 在情绪感染中实现降阈调节必须满足两个条件:一是“动机”, 即人们在内隐动机上有接受他人情绪感染的愿望, 如果没有这种动机, 则就有可能产生免疫性调节甚至反向情绪感染(如实验一)。通过事后询问被试得知, 被试均有试图摆脱“不成功”体验(烦躁体验)的动机, 摆脱消极情绪希望获得积极情绪也是出现情绪自我调节的原始动力, 而观看搞笑视频正好迎合了被试的这一动机。二是“降阈”, 即前情绪降低了人们体验后情绪的阈限, 实验中烦躁情绪降低了被试体验快乐情绪的阈限, 易感性就是对某种情绪感受阈限低, 感受灵敏的表现。例如, 积极的前情绪也会降低消极后情绪的体验阈限, 这就是为什么有些一帆风顺的生活却经不起小波浪的原因, 所不同的是, 这是一个“降阈”心理现象, 但并非是人际间的情绪感染现象。

本实验中之所以会发生降阈情绪感染, 与烦躁前情绪的归因有一定的关系。首先, 烦躁情绪是由事件原因造成的, 且不指向任何一个人, 如果消极情绪指向“人”, 可能就会演变为“攻击性的”消极情绪, 就不符合降阈情绪感染的实验条件。其次, 烦躁情绪是可控的, 因为被试可以选择自我调节或者离开实验(如果烦躁达到一定的程度时), 所以这种情境下的烦躁情绪是可调节的, 因此被试具有摆脱前情绪的愿望和接受快乐情绪的动机, 降阈情绪感染就发生了。

5 结论

(1)被试的仇恨前情绪使被试在观看“日本”搞笑视频时不但没有体验到快乐情绪, 反而加剧了被试的仇恨情绪体验, 出现了反向情绪感染。被试对“日本”搞笑视频没有丝毫积极性的评价, 甚至让被试对“日本”搞笑视频产生更低的评价。

(2)被试经历了三次不成功体验后, 在观看搞笑视频时能产生更大程度的积极情绪体验, 表明被试的消极前情绪对积极的情绪感染产生了易感性调节, 被试对视频的笑点评定也更加积极。说明前情绪具有“降阈”作用, 它降低了人们对相反情绪的感受阈限。

参考文献

Empathy in cooperative versus non-cooperative situations: The contribution of self-Report measures and autonomic responses

DOI:10.1007/s10484-012-9188-z URL [本文引用: 1]

Emotional contagion and trait empathy in prosocial behavior in young people: The contribution of autonomic (facial feedback) and Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES) measures

DOI:10.1080/13803395.2012.742492 URL [本文引用: 2]

Relationship between mood and susceptibility to emotional contagion: Is positive mood more contagious?

Emotional, psychophysiological and behavioral responses elicited by the exposition to cyberbullying situations: Two experimental studies

DOI:10.1016/j.pse.2016.02.003 URL [本文引用: 1]

Anger and happiness in virtual teams: Emotional influences of text and behavior on others’ affect in the absence of non-verbal cues

DOI:10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.06.002 URL [本文引用: 1]

Leading with emotion: An overview of the special issue on leadership and emotions

DOI:10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.07.002

URL

[本文引用: 1]

This introduction to the special issue on leadership and emotions provides an overview of the topic and articles included in this issue. We discuss the motivation behind this collection of theoretical and empirical articles, how they contribute to the goals of the issue and where we see this domain of leadership research heading in the future. One goal of this issue was to expand the focus of research beyond moods and generalized affect to discrete emotions and mechanisms through which emotions exert influence such as emotional contagion, empathy, and emotional authenticity. Relative to positive and negative affectivity, discrete emotions, mediators, and moderators of leader emotions have been studied far less. A second goal was to highlight the importance and role of emotion regulation strategies, mechanisms, and effects in the dynamic exchanges between leaders and followers. Finally, we wanted to increase the representation of multi-level perspectives and studies with regard to leadership and emotions. The compiled studies achieve these goals drawing on a variety of theoretical perspectives (e.g., Emotions as Social Information (EASI), Affective Events, Transformational leadership) as well as range of methods (qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods) and settings (lab and field). Taken together, the findings from this special issue illuminate some interesting relationships and we hope will inform future research on leadership and emotions in a significant way.

Evidence for unintentional emotional contagion beyond dyads

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0067371

URL

PMID:3696100

[本文引用: 1]

Little is known about the spread of emotions beyond dyads. Yet, it is of importance for explaining the emergence of crowd behaviors. Here, we experimentally addressed whether emotional homogeneity within a crowd might result from a cascade of local emotional transmissions where the perception of another’s emotional expression produces, in the observer's face and body, sufficient information to allow for the transmission of the emotion to a third party. We reproduced a minimal element of a crowd situation and recorded the facial electromyographic activity and the skin conductance response of an individual C observing the face of an individual B watching an individual A displaying either joy or fear full body expressions. Critically, individual B did not know that she was being watched. We show that emotions of joy and fear displayed by A were spontaneously transmitted to C through B, even when the emotional information available in B’s faces could not be explicitly recognized. These findings demonstrate that one is tuned to react to others’ emotional signals and to unintentionally produce subtle but sufficient emotional cues to induce emotional states in others. This phenomenon could be the mark of a spontaneous cooperative behavior whose function is to communicate survival-value information to conspecifics.

Empathy, emotional contagion, and rapid facial reactions to angry and happy facial expressions

DOI:10.1002/pchj.4

URL

PMID:26272762

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract The aim was to explore whether emotional empathy is related to the capacity to react with rapid facial reactions to facial expressions of emotion, and if emotional empathy is related to the ability to experience a similar emotion as expressed by another person. People high or low in emotional empathy were exposed to pictures of happy and angry faces while their facial electromyography from the zygomaticus major and corrugator supercilii muscle regions was detected. High empathy participants rapidly reacted with larger zygomatic muscle activity to happy as compared with angry faces as early as after 500 s after stimulus onset, and with larger corrugator muscle activity to angry than to happy faces after 500 s. Accordingly, this group also reacted with a corresponding experience of emotion. The low empathy participants, in contrast, did not differentiate between the happy and angry stimuli with either facial muscles or in their self experience of emotion. The findings are related to the facial feedback hypothesis and the results are interpreted as support for the hypothesis that rapid and automatically evoked facial mimicry may be one important mechanism for emotional and empathic contagion to occur.

Emotional empathy and facial reactions to facial expressions

DOI:10.1027/0269-8803/a000029

URL

[本文引用: 2]

This study investigates whether people high in emotional empathy are more facially reactive than are people low in emotional empathy when exposed to pictures of angry and happy facial expressions. Facial electromyographic activity was measured from the corrugator and the zygomatic muscle regions. In accordance with the predictions, the high empathic group reacted with larger corrugator activity to angry as compared to happy faces and with larger zygomatic activity to happy faces. However, the low empathic group did not differentiate between the angry and happy stimuli at all. The high empathic group, as compared to the low empathic group, also rated the angry faces as expressing more anger and the happy faces as being happier. It is concluded that high empathic people are particularly sensitive in reacting with facial reactions to facial expressions and that this ability is accompanied by a higher level of empathic accuracy.

Attention to emotion and non-western faces: Revisiting the facial feedback hypothesis

DOI:10.1080/00221309.2014.884052

URL

PMID:24846789

[本文引用: 1]

In a modified replication of Strack, Martin, and Stepper's demonstration of the Facial Feedback Hypothesis (1988), we investigated the effect of attention to emotion on the facial feedback process in a non-western cultural setting. Participants, recruited from two universities in Ghana, West Africa, gave self-reports of their perceived levels of attention to emotion, and then completed cartoon-rating tasks while randomly assigned to smiling, frowning, or neutral conditions. While participants with low Attention to Emotion scores displayed the usual facial feedback effect (rating cartoons as funnier when in the smiling compared to the frowning condition), the effect was not present in individuals with high Attention to Emotion. The findings indicate that (1) the facial feedback process can occur in contexts beyond those in which the phenomenon has previously been studied, and (2) aspects of emotion regulation, such as Attention to Emotion can interfere with the facial feedback process.

Telling lies: Clues to deceit in the marketplace, politics, and marriage

CiteSeerX - Scientific documents that cite the following paper: Telling lies: Clues to deceit in the marketplace, politics, and marriage

Keep smiling! Facial reactions to emotional stimuli and their relationship to emotional contagion in patients with schizophrenia

DOI:10.1007/s00406-007-0792-5 URL [本文引用: 1]

Young children’s affective responses to another’s distress: Dynamic and physiological features

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0121735 URL [本文引用: 1]

Emotion recognition from physiological signals

DOI:10.3109/03091902.2011.601784

URL

PMID:21936746

[本文引用: 2]

Abstract Emotion recognition is one of the great challenges in human-human and human-computer interaction. Accurate emotion recognition would allow computers to recognize human emotions and therefore react accordingly. In this paper, an approach for emotion recognition based on physiological signals is proposed. Six basic emotions: joy, sadness, fear, disgust, neutrality and amusement are analysed using physiological signals. These emotions are induced through the presentation of International Affecting Picture System (IAPS) pictures to the subjects. The physiological signals of interest in this analysis are: electromyogram signal (EMG), respiratory volume (RV), skin temperature (SKT), skin conductance (SKC), blood volume pulse (BVP) and heart rate (HR). These are selected to extract characteristic parameters, which will be used for classifying the emotions. The SVM (support vector machine) technique is used for classifying these parameters. The experimental results show that the proposed methodology provides in general a recognition rate of 85% for different emotional states.

Deficient cardiovascular stress reactivity predicts poor executive functions in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

DOI:10.1080/13803395.2010.493145 URL

Mood-congruent false memories persist over time

DOI:10.1080/02699931.2013.860016

URL

PMID:24294987

[本文引用: 1]

In this study, we examined the role of mood-congruency and retention interval on the false recognition of emotion laden items using the Deese/Roediger cDermott (DRM) paradigm. Previous research has shown a mood-congruent false memory enhancement during immediate recognition tasks. The present study examined the persistence of this effect following a one-week delay. Participants were placed in a negative or neutral mood, presented with negative-emotion and neutral-emotion DRM word lists, and administered with both immediate and delayed recognition tests. Results showed that a negative mood state increased remember judgments for negative-emotion critical lures, in comparison to neutral-emotion critical lures, on both immediate and delayed testing. These findings are discussed in relation to theories of spreading activation and emotion-enhanced memory, with consideration of the applied forensic implications of such findings.

Effects of music intervention with nursing presence and recorded music on psycho-physiological indices of cancer patient caregivers

DOI:10.1111/jcn.2012.21.issue-5-6 URL [本文引用: 1]

Facial electromyographic responses to emotional information from faces and voices in individuals with pervasive developmental disorder

DOI:10.1111/jcpp.2007.48.issue-11 URL [本文引用: 1]

Habituation of rapid sympathetic response to aversive timbre eliminated by change in basal sympathovagal balance

Degree of extraversion and physiological responses to physical pain and sadness

DOI:10.1111/sjop.12144

URL

PMID:25040459

[本文引用: 2]

Extraversion is a personality frequently discussed as one of the strongest and most consistent factors that relates to individual subjective wellbeing. The goal of this study was to better understand how people with varying degrees of extraversion psychologically and physiologically respond differently to unpleasant circumstances. Emotional responses (e.g., levels of intensity, valence, and arousal) were assessed in determining the sensitivity level to negative stimuli that were specifically designed to provoke physical pain and sadness emotion. Physiological changes (e.g., heart rate (HR), blood volume pulse (BVP), and respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA)) were also measured during pain and sadness to observe sympathetic and parasympathetic activities. Our results showed that the degree of extraversion was associated with less unpleasant responses to sadness, less HR responses to both pain and sadness, and greater RSA responses to sadness. The findings suggest that the lower HR reactivity to painful and sad situations and greater RSA reactivity to sad situations in extraversion could be possibly due to increased parasympathetic activity. Additionally, enhanced parasympathetic activity to negative situations may explain an important mechanism underlying the positive connection between extraversion and subjective wellbeing.

Is there more to blood volume pulse than heart rate variability, Respiratory sinus arrhythmia, and cardiorespiratory synchrony?

The emotional link: Leadership and the role of implicit and explicit emotional contagion processes across multiple organizational levels

DOI:10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.05.009 URL [本文引用: 1]

Spreading engagement: On the role of similarity in the positive contagion of team work engagement

DOI:10.5093/tr2013a21 URL [本文引用: 1]

Using reappraisal to regulate unpleasant emotional episodes: Goals and timing matter

DOI:10.1037/a0017109

URL

PMID:20001122

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract The hypothesis that cognitive reappraisal will have different effects on emotion as a function of regulatory goal and the timing with which reappraisals are enacted within an emotion episode was tested. Forty-one participants reappraised situations depicted in unpleasant pictures by imagining those situations getting worse (increase), staying the same (maintain), or getting better (decrease). Reappraisal instructions were delivered 2 s before (anticipatory) or 4 s after (online) picture onset. Measures of rated unpleasantness, expressive behavior (corrugator muscle activity), heart rate (HR), and electrodermal activity (EDA) were collected. Increase reappraisals produced higher rated unpleasantness, corrugator muscle activity, HR, and EDA relative to maintain reappraisals. For corrugator muscle activity and EDA, the effect of increase reappraisals was only apparent when enacted online. Decrease reappraisals produced lower rated unpleasantness relative to maintain reappraisals but had no effect on expressive behavior or autonomic physiology. The effect of decrease reappraisals did not depend on when reappraisal was enacted. These data underscore the importance of regulatory goals and the impact of regulatory timing as a moderator of emotion regulatory success within an emotion episode.

Emotional contagion and its relevance to individual behavior and organizational processes: A position paper

DOI:10.1007/s10869-011-9243-4 URL [本文引用: 1]

The older adult positivity effect in evaluations of trustworthiness: Emotion regulation or cognitive capacity?

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0169823 URL [本文引用: 3]

What is emotional contagion? The concept and mechanism of emotional contagion

情绪感染的概念与发生机制

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1042.2013.01596

URL

[本文引用: 3]

After studying the literature available about emotional contagion, we found that there existed two different perspectives in the concept of emotional contagion: One is primitive emotional contagion, which considers the emotional contagion as an automatic and unconscious process, and the other is conscious emotional contagion, which sees the emotional contagion as a consciousness-involved process. The reasons of the differences suggested researchers could not distinguish between types of emotional information, i.e. low-level emotional information and high-level emotional information, and between differences in emotional transference mechanism for the both. As a result, the meanings of emotional contagion expanded more and more, and could not indicate what the exact concept was. Disagreements on the concept of emotional contagion brought about a distinction between views of its mechanism. In this article we traced the origin of “contagion” in order to deduce what the emotional contagion is, and made clear what kind of emotional information could be transmitted by emotional contagion. We suggested that only low-level emotional information could be transferred by emotional contagion, and emotional contagion was an automatic, nonconscious process. At the end of the paper, the mechanism of emotional contagion was discussed on the base of above-defined concept and the literature available. The mechanism of emotional contagion: Perception→(Mimicry→Feedback (eliciting mirror neurons))→Emotion.

The regulation effect of antecedent view on emotional contagion: With examples of teaching activities

先入观念对情绪感染力的调节——以教学活动为例

The mechanism of emotional contagion

情绪感染的发生机制

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2016.01423

URL

[本文引用: 1]

原始性情绪感染理论认为,情绪感染是一个"情绪觉察—无意识模仿—生理反馈—情绪体验"的过程,情绪感染是一个由生理诱发情绪的过程。早在1884年,詹姆士和兰格就提出了情绪外周学说,同样描述了从身体变化到情绪变化的关系路径,但没有描述从刺激事件到外周身体变化的发生机制。对情绪感染的发生机制的研究能揭示这一"自下而上"的情绪产生机制。研究选取有效大学生被试62名,参与下列研究:(1)在眼动实验中使用情绪图片作为感官情绪信息,以考察觉察者的情绪觉察水平。(2)在生物反馈实验中,使用仿真课堂教学视频作为感官情绪信息,以考察觉察者的无意识模仿水平和生理反馈水平。使用路径分析证实了情绪感染的路径机制,在真实情境的诱发下,这种通过生理唤醒而诱发情绪的机制是可能的。