1 引言

概念隐喻理论认为, 隐喻是人类重要的思维方式, 是抽象概念得以表征的重要认知手段(Lakoff & Johnson, 2003)。从发生机制来看, 隐喻是从具体的始源域(source domain)到抽象的目标域(target domain)的系统映射(Kövecses, 2015; Landau, Robinson, & Meier, 2013)。语言学研究表明, 诸多文化和语言中都存在时空隐喻, 当中以空间概念为始源域, 以时间概念为目标域, 形成了不同种类的时空映射关系(Gijssels & Casasanto, 2017; Moore, 2014)。

心理学家发现, 时间和空间的映射关系不仅存在于外显的语言表达中, 同时也存在于人们的心智思维中, 研究者习惯将后者称之为“内隐时空映射(implicit space-time mappings)” (Casasanto, 2016, 2017; Casasanto & Jasmin, 2012; Li & Cao, 2017)。关于内隐时空映射方向的影响因素, 目前主要存在“隐喻构念观”和“时间焦点假设”两种观点。早期大量研究较为支持“隐喻构念观”, 认为人们的内隐时空映射主要受到语言表达的影响(Boroditsky, 2000)。具体来说, 说话者会根据语言中包含的外显时空映射关系, 有意识地在心理和思维层面建立起与语言表达相一致的时空映射关系。例如, Boroditsky (2001)发现, 与英语讲话者相比, 汉语讲话者的竖直方向时间隐喻表征更强, 存在“过去在上, 未来在下”的内隐时空映射。所以如此, 是由于汉语中具有更多数量的竖直时间隐喻。近期某些研究甚至表明语言在内隐时空隐喻映射的形成过程中具有因果作用。Hendricks和Boroditsky (2017)对缺乏竖直时间隐喻的英语讲话者进行了短期的时间语言训练, 如“早餐在晚饭上”, 当中蕴含了“过去在上, 未来在下”的隐喻关系。经过一段时间的训练, 被试在内隐时间认知中确实形成了对应的时空映射, 如对出现在屏幕上方表示较早时间的图片反应较快, 而对出现在屏幕下方表示较晚时间的图片反应较快。

虽然“隐喻构念观”得到了大量实验证据的支持, 但近年来有研究发现, 人们语言中的外显时空映射与其心智思维中的内隐时空映射并不总是一致, 有时甚至出现分离的状态。人们在说话时经常无意识地使用一些伴语手势(co-speech gesture)。心理学家认为, 时间手势是反映内隐时空隐喻映射的一个重要窗口(Casasanto & Jasmin, 2012; Li, 2017; Walker & Cooperrider, 2016; 李恒, 2016)。de la Fuente, Santiago, Román, Dumitrache, 和Casasanto (2014)发现, 虽然摩洛哥的大理亚语(Darija)和西班牙语一样, 语言表达中主要存在“未来在前, 过去在后”的时空映射, 但其伴语手势中却表现出相反的映射关系。这说明, 时间语言可能不是决定时间思维方式的唯一因素。

为进一步考察西班牙人和摩洛哥人的内隐时空映射, de la Fuente等人(2014)设计了一个时间图表任务进行考察, 实验结果与手势研究结论基本一致。研究者发现, 西班牙人倾向于将代表“未来”的物体放在身体前方, 而将代表“过去”的物体放在后方。与此不同的是, 摩洛哥人倾向于将代表“过去”的物体放在身体前方, 而将代表“未来”的物体放在后方, 说明其主要使用的是“过去在前, 未来在后”的内隐时空映射, 这与其语言中使用的时空映射刚好相反。

由于语言无法解释摩洛哥人时间语言和时间思维的分离, de la Fuente等人(2014)转而提出“时间焦点假设(Temporal Focus Hypothesis)”, 认为个体对过去和未来时间关注度的差异是导致不同文化中内隐时空映射多样性的主要动因。具体来说, 人们在感知过去和未来事件时, 可能存在不同的关注程度。注意力程度的差异可以从根本上影响内隐时空映射的联结方向。例如, 关注过去的个体更有可能形成“过去在前”的内隐时空映射, 关注未来的个体更有可能形成“未来在前”的内隐时空映射。这种对应关系可以通过具身认知理论得到解释。该理论认为, 身体是塑造认知的重要因素(Barsalou, 1999; 2016; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999; 叶浩生, 2011)。从日常经验来看, 人们习惯给予重要程度高的事物以更多的注意力, 比如将其放在身体前方可见的位置, 以免发生丢失。因此关注程度高的时间事件更有可能与空间方位上的前方发生联系, 形成特定的时空隐喻映射。

为验证这一假设, 研究者通过“时间焦点问卷(Temporal Focus Questionnaire)”考察了摩洛哥人和西班牙人对待过去和未来时间的文化态度。结果发现, 摩洛哥人重视过去, 关注传统生活方式, 是过去文化习俗的坚定传承者, 具有较强的“过去朝向思维”。西班牙人重视与未来相关的事物, 注重社会、经济和科技的发展, 具有较强的“未来朝向思维”。研究者综合两个实验的结果后提出:人们的内隐时空隐喻映射方向主要由认知主体的时间焦点所决定。具体来说, “过去朝向思维” 更有可能导致形成“过去在前”的内隐时空映射, “未来朝向思维”更有可能导致形成“未来在前”的内隐时空映射。

目前也有少数研究在中国文化中考察了“时间焦点假设”的解释力。Gu, Zheng和Swerts (2016)利用时间图表任务考察了中国内地被试的内隐时空映射。结果发现, 与de la Fuente等人(2014)实验中的西班牙语被试相比, 汉语母语被试偏好使用“过去在前”的时空映射。Gu等人 (2016)进一步引用Ji, Guo, Zhang和Messervey (2009)的研究, 认为中国人受到儒家思想影响, 更加重视传统文化, 表现出较强的“过去朝向思维”, 因此支持“时间焦点假设”。但需要指出的是, Ji等人的研究仅关注中国人的怀旧情绪, 没有考察被试对未来时间的关注度(如是否低于对过去时间的关注度)。更为重要的是, Gu等人(2016)研究中的中国被试实际上对两种前后时间隐喻模式的选择没有显著差异(36.8% vs. 63.2%, p = 0.14 by Sign Test)。之后一项针对中国青年未孕女性的研究同样表明, 被试在时间图表任务中对两种内隐时空映射没有表现出明显偏好, 对过去时间和未来时间也表现出相同的关注度, 为“时间焦点假设”提供了跨文化证据(Li & Cao, 2018)。但需要指出的是, 我国是一个多民族国家, 上述研究大多将中国被试当做一个整体加以考察, 难以准确反映出各民族语言的时间隐喻体系及其讲话者内隐时间认知方式的独特性。

大量研究发现, 在漫长的历史演进过程中, 各民族的生存环境和生活经验可能造就自身独特的时空隐喻系统。例如, 宋宜琪和张积家(2016)发现, 蒙古族人“年”的表达主要与草有关, 这是由于蒙古族人多从事畜牧业, 草场对于畜群的生存至关重要。与此不同的是, 西藏手语在表达“春”和“冬”时, 主要使用“冻土+融化”和“冻土+土冻紧”的手势。这是由于农业在西藏的经济结构中举足轻重。西藏作为中国最大冻土分布区之一, 冻土的融化程度会对农业生产活动产生直接影响(李恒, 吴玲, 吾根卓嘎, 2013)。

以往研究表明, 羌族在长期的历史发展过程中, “敬老”观念根深蒂固。尊敬老人作为中国羌族的基本行为规范, 不可触犯 (徐平, 2006)。例如, 羌族人在喜庆日子或招待宾客的咂酒仪式上, 通常先由年长者致开坛词, 以得到神灵庇佑, 然后依照辈份高低、年龄大小、主客身份顺序入座。即使在日常生活中路遇老人, 也要尊称并侧身让路。在礼俗性舞蹈时, 往往也由老人领唱领舞, 众人帮腔。从时间焦点来看, 羌族似乎与de La Fuente等人(2016)研究中的摩洛哥文化较为类似, 表现出明显的“敬老”特征。研究者认为, 这一特征主要体现的是珍惜传统、重视传承的心理认知特点。据此推断, 深受“敬老”而不”爱幼”思想观念影响的羌族人应当与摩洛哥人一样更加关注过去时间, 表现出强烈的“过去朝向思维”。与此不同的是, 虽然“尊老”是中华民族的传统美德, 如古语有云“老吾老以及人之老”, 现代社会也提倡在公共场合如地铁、公交等给老年人让座等行为。但对于汉族人而言, “尊老”主要是一种良好品德和文明礼仪, 很大程度上诉诸个体的自觉, 而非必须遵守的社会准则, 因此汉族人对过去时间的关注程度应当不如羌族人。此外, 汉族人在“尊老”的同时, 也提倡“爱幼”, 少年儿童代表了家庭的希望, 民族的未来。因此可以推测, 汉族人应当对过去和未来时间表现出相同的关注度。从心理学证据来看, “敬老”这一社会风俗文化对羌族人的认知心理确实具有重要影响。如李惠娟、张积家和张瑞芯(2014)从亲属词语义加工入手, 发现羌族被试对高辈分的亲属词的反应时比对低辈分的亲属词更短, 错误率也较低。研究者认为, 这主要与羌族对待老人和儿童态度不对称有关, 为羌族强烈的“敬老”观念的心理现实性提供了实证证据。

根据民族语言调查结果, 羌族虽有自己的语言, 但文字已经失传。使用羌语的人口(自称“日麦”)约有12万, 主要集中在四川阿坝州藏族羌族自治州的茂县、汶川、松潘等地, 但需要指出的是, 除中老年人(包括部分壮年人)外, 羌族青少年中会讲羌语的越来越少, 这为考察“隐喻构念观”和“时间焦点假设”提供了一个较为理想的群体。根据“隐喻构念观”, 如果语言是塑造人们时间认知的主要因素, 那么可以预测羌族人和汉族人受到汉语时空隐喻的影响, 二者的内隐时空映射应当一致; 反之, 如果时间焦点是影响人们内隐时空映射的主要因素, 那么可以预测羌族和汉族的内隐时空映射应当存在差异, 前者比后者更加关注过去时间, 因此也应当更加偏好使用“过去在前”的内隐时空映射。基于此, 本研究拟通过3个实验考察汉族和羌族的内隐时空映射及其时间焦点, 并尝试比较“隐喻构念观”和“时间焦点假设”二者的解释力。

2 实验1:汉族和羌族内隐时空映射的联结方向

2.1 被试

为保证研究的可信度, 减少随机误差, 实验1采用大样本调查, 样本量主要参考de La Fuente等人(2016)的研究。汉族被试为四川省广安市两所中学的102名高中生, 男生53人, 女生49人, 年龄在15至18岁之间, 平均年龄为15.7岁。羌族被试为四川省丹巴县和平武县两所中学的99名高中生, 男生45人, 女生54人, 年龄在15至19岁之间, 平均年龄为16.1岁。汉族和羌族被试均在公立高中就读, 教育背景相似, 母语均为汉语, 羌族被试没有掌握羌语。正式实验开始前, 被试采用5点量表自评汉语的熟练程度和使用频率(1=非常不熟练和非常不频繁, 5=非常熟练和非常频繁)。t检验表明, 两组被试的两项指标均无显著差异(t汉语熟练程度(199) = 1.07, t汉语使用频率(199) = 1.23, ps > 0.05)。所有被试视力或矫正视力正常, 皆为右利手。

2.2 设计

2(被试类型: 汉族/羌族) × 2(时空映射类型: 过去在前, 未来在后/过去在后, 未来在前)双因素混合设计。被试类型为被试间因素, 时空映射类型为被试内因素, 因变量是被试选择两种时空映射类型的比率。

2.3 材料和程序

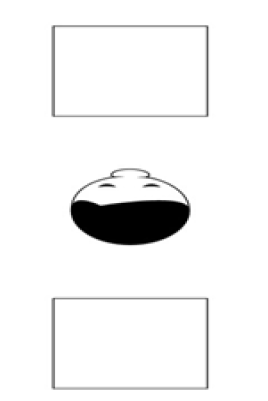

采用de la Fuente等人(2014)实验1中的时间图表任务(如图1所示), 要求被试通过纸笔测验完成。该任务因其实验目的隐蔽以及实验操作简便, 已成为考察内隐时空隐喻映射的重要范式, 在大量研究中得到应用(Gu et al., 2016; Li & Cao, 2017, 2018)。

图1

测试材料由一个卡通人物和两个正方形组成。卡通人物的正上方和正下方各有一个正方形。被试首先阅读一个小故事:图1中的卡通人物昨天去拜访了一名喜欢植物(动物)的朋友, 明天要去看望一名喜欢动物(植物)的朋友。要求被试将植物(用“植”表示)和动物(用“动”表示)写在他们认为合适的方框里(植物/动物与昨天/明天的对应关系以及呈现顺序在被试间平衡)。在这个实验中, 物体的空间位置与时间存在对应关系, 但无任何线索直接提示这种联系, 有效避免了被试利用语言中的时空隐喻进行回答的可能性, 因此可以较好地探测被试的内隐时空隐喻映射联结方向。实验要求被试根据直觉快速作答, 不要随意更改答案。受试被告知问题答案无对错之分,不允许相互讨论, 作答时也无需填写自己的真实姓名。

2.4 结果与分析

事后访谈表明, 所有被试明确实验任务, 却未猜到实验的真实目的, 故所有实验数据均有效。汉族和羌族被试的内隐时空映射选择人数以及比率如表1所示。

对2×2四格表进行费舍尔精确检验(Fisher’s exact test), 结果发现, 被试类型与时空映射方向交互作用显著, χ2(1) = 27.06, p < 0.001。这说明, 汉族被试和羌族被试对两类时空映射的选择存在明显差异。符号检验(Sign test)分析进一步表明, 汉族被试将表示过去时间的物体放在前方的比率(44.1%)与将表示未来时间的物体放在前方的比率没有显著差异(55.9%), p = 0.28。与此不同的是, 羌族被试将表示过去时间的物体放在前方的比率(79.8%)要比将表示未来时间的物体放在前方的比率显著地高(20.2%), p < 0.001。

实验1表明, 汉族被试对“过去在前”和“未来在前”两种内隐时空映射没有表现出明显的偏好, 而羌族被试更加倾向于使用“过去在前”的内隐时空映射。由于实验1汉族和羌族被试均使用汉语, 但二者的内隐时空映射具有显著差异。这说明, 语言可能不是影响两个民族内隐时间认知的主要因素, 不支持“隐喻构念观”。“时间焦点假设”认为, 对过去和未来时间的关注程度可以预测人们的内隐时空映射方向。虽然之前已有民族学研究发现, 羌族人的“敬老”观念根深蒂固, 可能表现出 “朝向过去”的心理倾向(徐平, 2006)。但仅从文化习俗推论羌族人比汉族人具有更加强烈的过去朝向时间思维不一定完全可靠。为了考察汉族人和羌族人的过去和未来时间焦点偏好, 设计了实验2。

3 实验2:汉族和羌族的时间焦点偏好

3.1 被试

同实验1。

3.2 设计

2(被试类型:汉族/羌族) ×2(时间焦点类型:过去/未来)双因素混合设计。被试类型为被试间变量, 时间焦点类型为被试内变量, 因变量是被试对不同时间焦点陈述的评分。

3.3 材料和程序

采用Shipp, Edwards和Lambert (2009)的“时间焦点量表(Temporal Focus Scale)”考察汉族和羌族被试对过去和未来时间的关注程度。实验2之所以没有采用de la Fuente等人(2014)的“时间焦点调查问卷”, 原因在于研究者没有验证该问卷的信度和效度, 因此难以将其直接用于对其他文化人群时间焦点的考察。此外, 该问卷中的某些表述可能不涉及时间焦点, 更像是对政治取向(如自由或保守等)的考察, 如“我认为全球化是积极的”。刘馨元和张志杰(2016)的研究表明, “时间焦点量表”可以较好地测试中国人对过去和未来时间的关注度, 区分不同的时间焦点。“时间焦点量表”的中文版由两位英语专业老师根据英文版翻译而成, 以确保两个版本在文化和语义上的对等性。问卷共包含12个以“过去” (4个)、现在(4个)和“未来” (4个)时间相关的陈述,如“我回想过去的记忆(I replay memories of the past in my mind)” (过去焦点), “我活在当下(I live my life in the present)” (现在焦点)和“我想象明天会为我带来什么(I imagine what tomorrow will bring for me)”。

被试在完成实验1的时间图表任务后, 继续回答“时间焦点量表”。要求被试仔细阅读每一句陈述, 并依据自身情况在7点量表上对陈述进行评分(1 = 从不, 3 = 有时, 5 = 经常, 7 = 总是)。所有受试完成题目后, 收回问卷。使用SPSS 20软件处理数据。

3.4 结果与分析

汉族和羌族被试对过去题目和未来题目的平均得分见表2。重复测量方差分析表明, 时间焦点类型主效应显著, F(1, 199) = 14.43, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.06。被试类型主效应不显著, F (1, 199) = 1.03, p = 0.313。被试类型与时间焦点类型的交互作用显著, F (1, 199) = 31.51, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.14。简单效应分析表明, 羌族被试对过去题目的评分(5.45)明显高于未来题目(4.48), p < 0.001, 并且其对过去题目的评分也高于汉族被试(4.95), p < 0.001。汉族被试对未来和过去题目的评分没有差异, p = 0.11, 但其对未来题目的评分(5.19)高于羌族被试(4.48), p < 0.001。汉族和羌族被试在现在维度题目上得分的差异均不显著, 并且与本实验假设无关, 故不作进一步分析。上述实验结果表明, 汉族人没有表现出明显的“朝向过去”或“朝向未来”的时间思维偏好, 而羌族被试表现出较强的“朝向过去”的时间思维, 这与以往民族学和人类学研究结果基本一致(韩云洁, 2014; 陈蜀玉, 2015)。

综合实验1和实验2结果, 汉族被试对“过去在前”和“未来在前”两种内隐时空映射没有表现出明显偏好, 对过去时间和未来时间的关注程度也大致相当。羌族被试更加偏好使用“过去在前”的内隐时空映射, 对过去时间的关注程度也更高。这说明, 汉族和羌族人的时间焦点能够较好地预测其内隐时空映射, 符合“时间焦点假设”的预言。

以往研究发现, 当抽象概念的空间位置与隐喻映射方向一致时, 就能够促进抽象概念表征的表征与加工, 导致出现“隐喻一致性效应”。例如, Rinaldi, Vecchi, Fantino, Merabet, & Cattaneo (2018)利用听觉呈现的时间概念分类任务发现, 意大利明眼人在“隐喻一致性”条件(未来在前, 过去在后)下的按键反应时快于“隐喻不一致”条件(过去在前, 未来在后)”, 而盲人对两种条件的反应时没有显著差异。所以如此, 是由于意大利明眼人存在“未来在前, 过去在后”的内隐时空映射, 而盲人由于缺少视觉经验, 无法形成系统性的时间前后表征。根据该实验范式, 如果实验1发现的内隐时空映射具有心理现实性, 可以预测其也会对汉族和羌族被试的时间概念加工产生影响。此外, 虽然实验1采取了大样本调查, 但其本质属于离线任务。为更加精确地考察汉族和羌族被试内隐时空映射的内部加工过程, 实验3试图在实验1的基础上, 利用时间概念分类的反应时任务进一步探讨这一问题。

4 实验3:内隐时空映射对汉族和羌族被试时间概念加工的影响

4.1 被试

实验3的被试与实验1来源相同。四川省丹巴县和平武县两所公立中学的36名羌族高中生, 男生19人, 女生17人, 年龄在15至18岁之间, 平均年龄为15.9岁。汉族被试为四川省广安市两所公立中学的42名高中生, 男生18人, 女生24人, 年龄在15至18岁之间, 平均年龄为16.3岁。所有被试母语均为汉语, 听力和视力正常, 皆为右利手。正式实验开始前, 被试采用5点量表自评汉语的熟练程度和使用频率(1=非常不熟练和非常不频繁, 5=非常熟练和非常频繁)。t检验表明, 两组被试的两项指标均无显著差异, t汉语熟练程度(76) = 0.79, t汉语使用频率(76) = 1.23, ps > 0.05。为避免实验间的相互影响, 所有被试均未参加实验1。

4.2 设计

2(被试类型:汉族/羌族) × 2(反应类型:一致/不一致)双因素混合设计。被试类型为被试间因素, 反应类型为被试内因素, 因变量是被试判断时间词位置的反应时和正确率。

4.3 材料

实验材料包含60个时间词, 表达过去的时间词 (如“昨天”)和表达未来的时间词(如“明天”)各30个。所有时间词均不包含表达空间方位的词素(如“前”或“后”等), 以避免空间词对实验结果造成影响。为了确保被试的判断不受时间词熟悉性影响, 60名不参加实验的高中生(汉族和羌族各30名)采用7点量表对时间词进行了熟悉度评定, 1表示非常不熟悉, 7表示非常熟悉。评定的结果表明, 汉族和羌族被试对过去词和未来词的熟悉度均高于6, 差异不显著(汉族:t (28) = 0.67, p = 0.82; 羌族:t (28) = 0.47, p = 0.68)。两组被试之间也不存在显著差异(过去词t (58) = 0.76, p = 0.45; 未来词:t (58) = 0.82, p = 0.42)。

请一位汉语本族语者以标准普通话正常语速朗读时间词并录音。录音采用Cool Edit Pro软件通过降噪麦克风采集, 采样率为44.1 kHz。经后期处理, 每个时间词音频的起点和终点为该词发音的前后各100 ms。将60个时间词随机分为两个区组, 每个区组各包含15个过去时间词和15个未来时间词。为两个区组匹配时间词位置类型, 包含一致和不一致两种条件。实验1发现, 羌族被试倾向于使用“过去在前, 未来在后”的时空映射, 为行文方便, 故实验3将一致条件定为“过去在前/未来在后”, 不一致条件定为“未来在前/过去在后”。一致和不一致类型在两个区组间进行了平衡。每位被试均接受两个区组的测试。测试时, 区组内时间词的呈现顺序随机化处理, 但过去和未来时间词交替出现。

4.4 程序

采用听觉呈现的时间词分类任务。实验在安静的房间内进行, 利用基于MATLAB软件的Psychtoolbox编程, 仪器为联想台式电脑。时间词分类采用键盘按键方式实现。键盘使用87键无线机械键盘。为保证数据采集的准确性, 防止被试误按, 仅保留键盘中的“A”、“G”、“L”键, 去掉其他键的键帽。测试时, 将键盘水平旋转90°, 呈竖直摆放状态, 使“L”键位于键盘前方, “G”键居中, “A”位于键盘后方。“G”键为音频播放控制键, “L”键和“A”键为反应键。测试时, 被试需持续按住“G”键, 以播放音频中的时间词, 直至做出按键判断。松开“G”键与按“L”或“A”键的间隔时间为被试的判断反应时。

实验时, 被试端坐在计算机前70 cm处, 并佩戴耳机。正式测试开始前, 被试首先进行练习测试。练习测试使用4个时间词, 过去词和未来词各两个(不在正式实验中出现), 其余步骤和要求与正式实验完全相同。被试报告熟悉实验程序后开始正式测试。计算机屏幕首先呈现指导语, 要求被试阅读有关时间词位置类型的说明, 并依据说明对耳机中播放的时间词位置做出判断。如指导语为“听到未来时间词请按“L”键, 听到过去时间词请按“A”键”, 被试需:1)按“G”键播放音频; 2)仔细听音频中的时间词; 3)根据听到的时间词做出相应的按键反应。如指导语为听到未来时间词请按“A”键, 听到过去时间词请按“L”键”, 则按键模式相反。被试按键判断后进入下一试次。如被试在2000 ms内未作反应, 程序自动进入下一试次。计算机自动记录被试的判断反应时和正确率。

4.5 结果

被试的错误率很低且均衡分布, 不足5%, 故未做统计分析。反应时分析时删去未反应、错误反应以及反应时在M ± 2.5 SD之外的数据, 占全部数据的4.3%。结果见表3。

反应时的重复测量方差分析表明, 反应类型主效应显著, F1 (1, 76) = 34.68, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.31, F2 (1, 58) = 29.44, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.34。被试类型主效应不显著, F1 (1, 76) < 1, p > 0.05, F2 (1, 58) < 1, p > 0.05。反应类型和被试类型交互效应显著, F1 (1, 76) = 31.21, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.29, F2 (1, 58) = 36.97, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.39。简单效应分析显示, 对于羌族被试而言, 对一致条件的按键反应时快于不一致条件, p < 0.001。对于汉族被试而言, 不一致条件和一致条件的按键反应时没有差异, p = 0.879。

实验3表明, 当时间词隐含的空间关系与按键位置一致时, 被试的反应更快; 当时间词隐含的空间关系与按键位置不一致时, 被试的反应更慢, 即存在时空映射关系与按键空间位置的“隐喻一致性效应”。具体而言, 羌族人主要存在“过去在前, 未来在后”的内隐时空映射。与此不同的是, 汉族人对“过去在前/未来在后”和“未来在前/过去在后”两种内隐时空映射没有偏好, 因此两种条件下的按键反应时没有差异。上述发现进一步印证了实验1的实验结果。结合实验2中汉族和羌族被试的时间焦点倾向, 可以发现对过去时间和未来时间的关注度确实可以预测二者的内隐时空映射方向, 为“时间焦点假设”提供了支持证据。

5 总体讨论

5.1 汉、羌族内隐时空映射的选择偏好

人们在身体与世界互动的过程中产生了概念, 然而概念有具体和抽象之分, 二者的表征方式也有所不同(Paivio, 1971, 1990; Binder, Westbury, McKiernan, Possing, & Medler, 2005)。概念隐喻理论认为, 隐喻是人们识解世界的方式, 是我们对世界加以概念化的一个必不可少、习以为常的方法。隐喻的本质乃是用一个简单、具体而又可及的认知域, 去理解另一个复杂、抽象而难以触及的认知域。例如, 时间等抽象概念主要借助具体概念, 通过隐喻加以表征(Lakoff & Johnson, 2003)。空间是人类生产生活的基本场所, 主体可以通过身体与空间接触获得直接经验, 使其构成人类概念系统的核心。与此不同的是, 由于人类无法通过身体经验直接表征时间, 便习惯以空间经验为基础, 采用隐喻认知的方法, 将空间域的知识投射到时间域, 从而完成对时间概念的表征, 并且形成了各式各样的时空映射。

实验1利用时间图表任务考察了汉族和羌族内隐时空映射的联结方向。在羌族人的时间概念表征中, 存在着“过去在前, 未来在后”的内隐时空映射, 而在汉族人的时间概念表征中, 对“过去在/未来在后前”和“未来在前/过去在后”两种内隐时空映射没有表现出明显偏好。然而, 由于汉族和羌族被试均使用汉语, 但其内隐时空映射却存在差异。这说明, 语言不是决定二者内隐时间认知的因素。基于“时间焦点假设”, 实验2考察了汉族和羌族被试对过去时间和未来时间的关注程度。结果发现, 前者没有表现出明显的心理时间朝向, 过去焦点和未来焦点评分不存在显著差异, 后者则表现出强烈的“朝向过去”的心理倾向。这说明, 时间焦点能够较好地预测汉族和羌族人的内隐时空映射联结方向, 支持“时间焦点假设”。

实验3利用概念分类任务进一步考察了汉族和羌族人的内隐时空映射是否有利于促进其在对应的空间位置对时间词汇做出反应。结果发现, 羌族被试在一致性条件下(过去在前, 未来在后)的反应时快于不一致条件(过去在后, 未来在前)。这说明, 羌族确实存在“过去在前, 未来在后”的内隐时空映射, 并且这种映射有利于促进时间概念的表征和加工, 从而出现了“隐喻一致性效应”。与此不同的是, 汉族被试两种条件下的反应速度没有显著差异。Fuhrman等人(2011)提出, 这可能是由于实验范式不够敏感, 无法探测人们前后方向上的内隐时间表征。但从羌族被试的反应模式上来看, 该种解释似乎站不住脚。因此, 一种更加可能的解释是:汉族人对“过去在前”和“未来在前”两种内隐时空映射具有相同的偏好, 可以在内隐的时间认知中将“过去”和“未来”两类时间概念与任何一种空间关系进行对应, 因此键盘位置不会对时间概念分类产生显著影响。

5.2 语言是否能够影响汉族人和羌族人的时间认知

本研究实验1和实验3表明, 汉族人对“过去在前”和“未来在前”两种隐喻映射的选择没有偏好, 这既与汉族人同等关注和过去和未来一致, 也符合汉语中利用“前”指向过去和指向未来的表达相一致, 同时支持“隐喻构念观”和“时间焦点假设”。但需要指出的是, 人们的内隐时空映射具有较大的灵活性和可塑性, 即便是生活在同一文化以及使用同一种语言的群体, 其内隐时空映射也可能存在差异。这说明, 语言可能不是决定人们时间认知的唯一因素。例如, de la Fuente等人(2014)发现, 相比较于西班牙年轻人, 西班牙老年人更加偏好使用“过去在前”的内隐时空映射。这是由于年龄的增长可能引发老年人怀旧情绪的增加, 导致其更加关注过去事件。Li和Cao (2018)也发现, 相比于汉族未孕女性, 汉族怀孕女性更加倾向于使用“未来在前”的时空映射。所以如此, 是由于女性怀孕后, 母亲角色的转换会引发其对未来生活和未来事件的深入思考和重新规划, 如权衡工作和家庭的比重, 关注后代的良好发展等, 从而导致个体对未来表现出更高的关注度(李爱梅, 彭元, 熊冠星, 2015)。上述研究结果表明, 除语言外, 可能还存在着其他影响时间认知的因素, 如与时间焦点相关的文化态度和个体差异等。

本研究实验结果同时发现, 羌族人倾向于使用“过去在前, 未来在后”的时空映射, 并且这种映射关系对其时间概念加工具有促进作用, 出现了时空隐喻的一致性效应。以往研究指出, 某些文化族群心智思维中存在的“过去在前、未来在后”的时空映射主要来源于语言中的视觉标记。如Núñez和Sweetser (2006)发现, 艾依玛拉语(Aymara)讲话者不仅在口语中习惯使用“过去在前、未来在后”的时空映射, 并且在其内隐认知中(如伴语手势)也倾向于将过去放在前面, 将未来放在后面。研究者认为, 这主要是由于艾依玛拉语在表达信息/知识的来源时, 必须使用表示言据性(evidentiality)的语法标记, 表明其是否为亲眼所见, 因此视觉对于讲话者而言尤为重要。按照一般经验, 过去是已经经历过的时间, 具有较高的可见度, 因此艾依玛拉人倾向于将其放在身体(眼睛)的前方。然而, 未来看不见、摸不着, 也很难被预知, 因此艾依玛拉人倾向于将其放在身体的(眼睛)的后方, 表示可见度低。Sullivan和Bui (2016)发现, 越南语中也存在类似的“过去在前, 未来在后”时空映射。研究者指出, 虽然越南语缺乏与艾依玛拉语类似的言据性标记, 但前者的语言指示系统中却存在视觉标记, 用于标示物体的可见性。例如, 越南语中存在nọ和kia两个远指代词, 虽然都表示“那个”的意思, 但前者主要用于指代不可见的物体, 而后者表示指称物可见, 二者用法不可混淆。由此可见, 语法中的视觉标记是影响艾依玛拉语和越南语时间认知方式的重要因素。然而, 本研究中的羌族人在其日常交流中主要使用汉语, 汉语的语法系统中却缺乏与艾依玛拉语和越南语类似的视觉标记。此外, 汉语中同时存在“过去在前”和“未来在前”两种隐喻映射, 但使用汉语的羌族人却表现出对“过去在前”时空映射的强烈偏好。这说明, 语言可能不是决定羌族人使用“过去在前, 未来在后”的唯一因素。相反, 羌族对过去和未来时间的关注程度可以较好地预测其内隐时空映射的方向, 为“时间焦点假设”提供了支持证据。

综合上述实验结果以及前人研究可以发现, 时间认知系统具有较大的灵活性和可变性, 包括语言和文化在内的诸多因素都会对人们的时间焦点造成影响, 从而导致内隐时空隐喻映射的联结方向发生改变。一方面, 语言塑造人们的心理时间表征。语言中包含的时空隐喻表达会影响人们的时间认知和心理特点, 从而导致时间思维方式出现跨文化差异。另一方面, 虽然人们的时间语言使用总是保持较为稳定的状态, 但其内隐时空映射方向却可能随着个体和环境的变化而发生改变。这说明, 时间焦点具有较强的灵活性, 人们可以根据自己的需要, 将注意力合理分配到过去、现在和未来事件上。从进化的角度来看, 时间焦点与外部环境需要的匹配程度对于人类生存至关重要(Gibson, Waller, Carpenter, & Conte, 2007; Huy, 2001), 并由此导致了人们内隐时空映射方向的改变。对于复杂的人类时间认知系统而言, “隐喻构念观”和“时间焦点假设”可能各具解释效力, 只有将二者结合起来才有可能对时间思维方式背后的认知机制做出更加全面合理的解释。

5.3 汉族和羌族文化中时间焦点的差异

以往有研究发现, 受儒家思想影响, 中国人表现出比较强烈的“过去朝向思维”。如Ji等人(2009)通过比较中国人和加拿大人发现, 前者对过去信息的记忆程度好于后者, 这可能源于前者对过去时间的关注程度更高。但需要指出的是, 这一结论主要基于中国被试和西方被试的比较, 没有考虑到中国文化内部可能存在的民族差异。实验2利用时间焦点量表考察了汉族和羌族被试对过去和未来时间的重视程度。结果发现, 羌族人对过去时间的重视程度高于汉族被试, 而汉族被试对过去时间和未来时间没有表现出明显的偏好。这一发现与已有的民族学研究结果基本一致。羌族具有“敬老”而不“爱幼”的文化传统, 容易让人产生一种“朝向过去”的心理时间朝向。这种心理时间朝向至今仍然表现在羌族人生活的方方面面, 如羌族丧葬释比经典蕴含着丰富的终极关怀意识。通过追悼死者而表现的感恩观、慎终的报恩观以及归祖的送亡观, 寄托着生者无尽的感恩情结, 充满了强烈的孝道观念(董常保, 王利明, 2012)。

与之不同, 汉族人未对过去时间表现出更高的关注度, 可能与其既“尊老”亦“爱幼”的文化习俗有关。与此同时, 汉族人对“敬老” “孝道”等观念的践行可能要弱于羌族人。例如, 现代社会的汉族人重“侍生”轻“侍死”, 重视父母生前与自己的情感关系, 淡化父母去世后的丧葬祭念问题, 这与羌族人认为“侍生”和“侍死”同等重要的孝道观念存在一定差异。陈娇娇(2016)发现, 随着社会经济的飞速发展, 孝道在当代汉族大学生身上出现了滑坡现象, 发生了不同程度的问题。范丰慧、汪宏、黄希庭、史慧颖和夏凌翔(2009)也发现, 顺亲延亲作为“孝道”观念的重要维度, 由于家庭结构和和功能的变迁, 计划生育政策的影响, 延续家庭血脉的观念在当代社会趋于式微。例如, 本研究中的汉族被试绝大多数都为独生子女, 而羌族被试大多出生并生活在在多子女家庭。因此, 现代生活方式、文化设计以及国家政策等因素都有可能淡化汉族人的传统孝道观念, 削弱其“过去朝向思维”。

6 结论

(1)羌族人主要使用“过去在前”的内隐时空映射, 汉族人对“过去在前”和“未来在前”两种隐喻映射关系没有明显偏好。

(2)内隐时空映射影响汉族和羌族被试时间概念的在线加工, 导致出现“隐喻一致性效应”。

(3)汉族和羌族的内隐时空映射联结方向主要受到二者对过去和未来时间关注程度的影响, 符合“时间焦点假设”的预测。

参考文献

Perceptual symbol systems

On staying grounded and avoiding Quixotic dead ends

DOI:10.3758/s13423-016-1028-3

URL

PMID:27112560

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract The 15 articles in this special issue on The Representation of Concepts illustrate the rich variety of theoretical positions and supporting research that characterize the area. Although much agreement exists among contributors, much disagreement exists as well, especially about the roles of grounding and abstraction in conceptual processing. I first review theoretical approaches raised in these articles that I believe are Quixotic dead ends, namely, approaches that are principled and inspired but likely to fail. In the process, I review various theories of amodal symbols, their distortions of grounded theories, and fallacies in the evidence used to support them. Incorporating further contributions across articles, I then sketch a theoretical approach that I believe is likely to be successful, which includes grounding, abstraction, flexibility, explaining classic conceptual phenomena, and making contact with real-world situations. This account further proposes that (1) a key element of grounding is neural reuse, (2) abstraction takes the forms of multimodal compression, distilled abstraction, and distributed linguistic representation (but not amodal symbols), and (3) flexible context-dependent representations are a hallmark of conceptual processing.

Distinct brain systems for processing concrete and abstract concepts

DOI:10.1162/0898929054021102 URL [本文引用: 1]

Metaphoric structuring: Understanding time through spatial metaphors

DOI:10.1016/S0010-0277(99)00073-6

URL

PMID:10815775

[本文引用: 1]

The present paper evaluates the claim that abstract conceptual domains are structured through metaphorical mappings from domains grounded directly in experience. In particular, the paper asks whether the abstract domain of time gets its relational structure from the more concrete domain of space. Relational similarities between space and time are outlined along with several explanations of how these similarities may have arisen. Three experiments designed to distinguish between these explanations are described. The results indicate that (1) the domains of space and time do share conceptual structure, (2) spatial relational information is just as useful for thinking about time as temporal information, and (3) with frequent use, mappings between space and time come to be stored in the domain of time and so thinking about time does not necessarily require access to spatial schemas. These findings provide some of the first empirical evidence for Metaphoric Structuring. It appears that abstract domains such as time are indeed shaped by metaphorical mappings from more concrete and experiential domains such as space.

Does language shape thought? Mandarin and English speakers’ conceptions of time

DOI:10.1006/cogp.2001.0748

URL

PMID:11487292

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract Does the language you speak affect how you think about the world? This question is taken up in three experiments. English and Mandarin talk about time differently--English predominantly talks about time as if it were horizontal, while Mandarin also commonly describes time as vertical. This difference between the two languages is reflected in the way their speakers think about time. In one study, Mandarin speakers tended to think about time vertically even when they were thinking for English (Mandarin speakers were faster to confirm that March comes earlier than April if they had just seen a vertical array of objects than if they had just seen a horizontal array, and the reverse was true for English speakers). Another study showed that the extent to which Mandarin-English bilinguals think about time vertically is related to how old they were when they first began to learn English. In another experiment native English speakers were taught to talk about time using vertical spatial terms in a way similar to Mandarin. On a subsequent test, this group of English speakers showed the same bias to think about time vertically as was observed with Mandarin speakers. It is concluded that (1) language is a powerful tool in shaping thought about abstract domains and (2) one's native language plays an important role in shaping habitual thought (e.g., how one tends to think about time) but does not entirely determine one's thinking in the strong Whorfian sense. Copyright 2001 Academic Press.

Temporal language and temporal thinking may not go hand in hand

DOI:10.1075/hcp.52.04cas

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Typically in English metaphors, time appears to flow along the speaker's sagittal axis: deadlines lie ahead of us or behind us; we can look forward to our golden days or look back on our childhood. Time is metaphorized as a horizontal line extend- ing indefinitely ahead of and behind the speaker (Clark 1973; Nunez and Sweetser 2006). These expressions are deictic insomuch as earlier and later times are located on a mental timeline with respect to a speaker who stands metaphorically at a now point, facing toward the future (which is ahead) and away from the past (which is behind the speaker).Deictic expressions about earlier and later times often use spatial terms that specify a direction on the sagittal axis (1a-b).

Relationships between language and cognition.

The hands of time: Temporal gestures in English speakers

DOI:10.1515/cog-2012-0020

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Do English speakers think about time the way they talk about it? In spoken English, time appears to flow along the sagittal axis (front/back): the future is ahead and the past is behind us. Here we show that when asked to gesture about past and future events deliberately, English speakers often use the sagittal axis, as language suggests they should. By contrast, when producing co-speech gestures spontaneously, they use the lateral axis (left/right) overwhelmingly more often, gesturing leftward for earlier times and rightward for later times. This left-right mapping of time is consistent with the flow of time on calendars and graphs in English-speaking cultures, but is completely absent from conventional spoken metaphors. English speakers gesture on the lateral axis even when they are using front/back metaphors in their co-occurring speech. This speech-gesture dissociation is not due to any lack of lexical or constructional resources to spatialize time laterally in language, nor to any lack of physical resources to spatialize time sagittally in gesture. We propose that when speakers are describing sequences of events, they often use neither the Moving Ego nor Moving Time perspectives. Rather, they adopt a oving Attention perspective, which is grounded in patterns of interaction with cultural artifacts, not in patterns of interaction with the natural environment. We suggest possible pragmatic, kinematic, and mnemonic motivations for the use of a lateral mental timeline in gesture and in thought. Gestures reveal an implicit spatial conceptualization of time that cannot be inferred from language.

The present situation of filial piety and its education in contemporary college students (Unpublished master’s thesis)

当代大学生孝道现状及其教育研究(硕士学位论文)

Qiang culture.

羌族文化

When you think about it, your past is in front of you: How culture shapes spatial conceptions of time

DOI:10.1177/0956797614534695 URL [本文引用: 8]

A discussion on standards of filial piety in Qiang’s funeral

羌族丧葬释比中的孝道观略论

The cognitive structure of filial piety in Contemporary Chinese

当代中国人的孝道认知结构

How linguistic and cultural forces shape conceptions of time: English and mandarin time in 3D

DOI:10.1111/j.1551-6709.2011.01193.x

URL

PMID:21884222

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract In this paper we examine how English and Mandarin speakers think about time, and we test how the patterns of thinking in the two groups relate to patterns in linguistic and cultural experience. In Mandarin, vertical spatial metaphors are used more frequently to talk about time than they are in English; English relies primarily on horizontal terms. We present results from two tasks comparing English and Mandarin speakers temporal reasoning. The tasks measure how people spatialize time in three-dimensional space, including the sagittal (front/back), transverse (left/right), and vertical (up/down) axes. Results of Experiment 1 show that people automatically create spatial representations in the course of temporal reasoning, and these implicit spatializations differ in accordance with patterns in language, even in a non-linguistic task. Both groups showed evidence of a left-to-right representation of time, in accordance with writing direction, but only Mandarin speakers showed a vertical top-to-bottom pattern for time (congruent with vertical spatiotemporal metaphors in Mandarin). Results of Experiment 2 confirm and extend these findings, showing that bilinguals representations of time depend on both long-term and proximal aspects of language experience. Participants who were more proficient in Mandarin were more likely to arrange time vertically (an effect of previous language experience). Further, bilinguals were more likely to arrange time vertically when they were tested in Mandarin than when they were tested in English (an effect of immediate linguistic context).

Antecedents, consequences, and moderators of time perspective heterogeneity for knowledge management in MNO teams

DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1379 URL [本文引用: 1]

Conceptualizing time in terms of space: Experimental evidence In B Dancygier (Ed), Cambridge handbook of cognitive linguistics (pp 651-668) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Experimental evidence

Which is in front of Chinese people: Past or Future?: A study on Chinese people’s space-time mapping

The heritage and education of Qiang culture

羌族文化传承与教育

《羌族文化传承与教育》从教育人类学视角出发,系统深入地探讨羌族文化传承与教育的若干问题,力图借鉴多学科的知识与研究成果,广泛涉及民族教育学、教育文化学、文化社会学、文化学、心理学等多学科理论知识,探索传统文化对幼儿发展的影响及其在幼儿教育中的应用规律,阐述羌族艺术文化传承与教育实践的关系以及两者有效衔接的思路。《羌族文化传承与教育》全书共分为十一章,从回顾羌族历史变迁的概况开始,述评近年来羌族文化研究取得的成果及其局限性,提出羌族文化传承与民族教育发展的一些思路、策略等,以此试图构建了羌族文化传承与教育内源性发展的有效联动机制。

New space-time metaphors foster new nonlinguistic representations

DOI:10.1111/tops.12279

URL

PMID:28635107

[本文引用: 1]

react-text: 397 In this paper we examine how English and Mandarin speakers think about time, and we test how the patterns of thinking in the two groups relate to patterns in linguistic and cultural experience. In Mandarin, vertical spatial metaphors are used more frequently to talk about time than they are in English; English relies primarily on horizontal terms. We present results from two tasks comparing... /react-text react-text: 398 /react-text [Show full abstract]

Time, temporal capability, and planned change

DOI:10.2307/3560244

URL

[本文引用: 1]

I propose four ideal types of planned change processes, each with distinct temporal and nontemporal assumptions, and each associated with altering a distinct organizational element. These types are commanding, engineering, teaching, and socializing. I then argue that large-scale change involves an alteration of multiple organizational elements, thus requiring enactment of multiple intervention ideal types. This requires change agents to display temporal capability skills to effectively sequence, time, pace and combine various interventions.

Looking into the past: Cultural differences in perception and representation of past information

Where metaphors come from: Reconsidering context in metaphor.

DOI:10.1080/00437956.2016.1141949

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract The book argues that the use of metaphors does not depend simply on preestablished metaphorical structures in the conceptual system. Instead, metaphors arise as a result of contextual influences. The mind is in constant interaction with the situational, discourse, conceptual-cognitive, and bodily contexts.

Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to western thought.

The power of metaphor: Examining its influence on social life.

Are pregnant women more foresighted? The effect of pregnancy on intertemporal choice

孕妇更长计远虑?——怀孕对女性跨期决策偏好的影响

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1041.2015.01360

URL

We tested our hypotheses by using a quasi-experiment design (Study 1) and an experiment design (Study 2). Pregnant women were recruited in Study 1, and non-pregnant women were primed with maternal mind set in Study 2. In both studies, control groups were non-pregnant women without any manipulation. All the participants in both studies completed the Consideration of Future Consequences Scale (Strathman, Gleicher, Boninger, & Edwards, 1994; α = 0.71) and Intertemporal Decision-making Tasks (Wang & Dvorak, 2010). In Study 3, we manipulated future orientation to determine whether it was causally related to intertemporal decision. The manipulations in Study 2 and Study 3 were both successful. They showed that pregnant women were more future-oriented than their peer control groups. Pregnant women had a much lower delay discounting rate in intertemporal decision-making. Furthermore, it was found that the level of future orientation mediated this effect.This research explored the differences in intertemporal choice between pregnant women and their peer group. Our results revealed that pregnant women had a ‘maternal mind’ which focuses more on future events. This mindset promotes future-orientation and a greater preference for LL options in intertemporal choice.

The psychological reality of spatial metaphors for time—Evidence form gesture and sign language.

时空隐喻的心理现实性: 手势和手语的视角

Time on hands: Deliberate and spontaneous temporal gestures by speakers of Mandarin

DOI:10.1075/gest.00002.li

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract The present study investigates deliberate and spontaneous temporal gestures in Mandarin speakers. The results of our analysis show that when asked to gesture about past and future events deliberately (Study 1), Mandarin speakers tend to mimic space-time mappings in their spoken metaphors or graphic conventions for time in Chinese culture, including sagittal mappings (front/past, back/future), vertical mappings (up/past, down/future), and lateral mappings (left/past, right/future). However, in their spontaneous co-speech gestures about time (Study 2), more congruent gestures were produced on the lateral axis than on the vertical axis. This suggests that although Mandarin speakers could think about time vertically, they still showed a horizontal bias in their conceptions of time. Speakers were also more likely to gesture according to future-in-front mappings despite more past-in-front mappings found in spoken Chinese, suggesting a dissociation of temporal language and temporal thought. These results demonstrate that gesture is useful for revealing the spatial conceptualization of time.

Personal attitudes toward time: The relationship between temporal focus, space-time mappings and real life experiences

DOI:10.1111/sjop.2017.58.issue-3 URL [本文引用: 2]

The hope of the future: The experience of pregnancy influences women’s implicit space-time mappings

DOI:10.1080/00224545.2017.1297289 URL [本文引用: 3]

A cognitive study of metaphor and metonymy of time in Tibetan Gesture Language

西藏手语时间隐喻和转喻的认知研究

The vertically spatial metaphors of kinship words of Qiang nationality

上下意象图式对羌族亲属词认知的影响

The modulation of temporal focus on the effect of spatial-temporal association of response codes.

不同时间关注点下的空间-时间联合编码效应

With the future behind them: Convergent evidence from Aymara language and gesture in the crosslinguistic comparison of spatial construals of time

DOI:10.1207/s15516709cog0000_62 URL [本文引用: 1]

Mental representations: A dual-coding approach

DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195066661.001.0001

[本文引用: 1]

Abstract This work presents a systematic analysis of the psychological phenomena associated with the concept of mental representations - also referred to as cognitive or internal representations. A major restatement of a theory the author of this book first developed in his 1971 book (Imagery and Verbal Processes), this book covers phenomena from the earlier period that remain relevant today but emphasizes cognitive problems and paradigms that have since emerged more fully. It proposes that performance in memory and other cognitive tasks is mediated not only by linguistic processes but also by a distinct nonverbal imagery model of thought as well. It discusses the philosophy of science associated with the dual coding approach, emphasizing the advantages of empiricism in the study of cognitive phenomena and shows that the fundamentals of the theory have stood up well to empirical challenges over the years.

The ego-moving metaphor of time relies on visual experience: No representation of time along the sagittal space in the blind

DOI:10.1037/xge0000373 URL [本文引用: 1]

Conceptualization and measurement of temporal focus: The subjective experience of the past, present, and future

DOI:10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.05.001 URL [本文引用: 1]

Ethnic differences in time metaphor cognition

时间隐喻认知具有民族差异性

With the future coming up behind them: Evidence that Time approaches from behind in Vietnamese

DOI:10.1515/cog-2015-0066

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Vietnamese speakers can describe the future as behind them and gesture forwards to indicate the past, which suggests they use a conceptual model of Time in which the future is behind and the past is in front. This type of model has previously been shown to be pervasive only among older speakers of Aymara in the Andes (Nú09ez and Sweetser 2006. With the future behind them: Convergent evidence from Aymara language and gesture in the crosslinguistic comparison of spatial construals of time.Cognitive Science30. 401–450). Whereas Time in the Aymara model does not “move”, the present data show that Time in Vietnamese can “approach” from behind the Ego and “continue forward” into the past. To our knowledge, no other language has been identified with a model where Time moves from behind Ego to in front. Recognition of this model in Vietnamese will open up new research opportunities, particularly since the model does not seem to be endangered in Vietnamese.

The continuity of metaphor: Evidence from temporal gestures

DOI:10.1111/cogs.12254

URL

PMID:26059310

[本文引用: 1]

Reasoning about bedrock abstract concepts such as time, number, and valence relies on spatial metaphor and often on multiple spatial metaphors for a single concept. Previous research has documented, for instance, both future-in-front and future-to-right metaphors for time in English speakers. It is often assumed that these metaphors, which appear to have distinct experiential bases, remain distinct in online temporal reasoning. In two studies we demonstrate that, contra this assumption, people systematically combine these metaphors. Evidence for this combination was found in both directly elicited (Study 1) and spontaneous co-speech (Study 2) gestures about time. These results provide first support for the hypothesis that the metaphorical representation of time, and perhaps other abstract domains as well, involves the continuous co-activation of multiple metaphors rather than the selection of only one.

Cultural adaptation and change: Sichuan Qiang survey

文化的适应和变迁: 四川羌村调查

本书详尽地分析了羌村人的经济生活模式、社会构建和运转、个人与社会的关系、精神世界构造等,在对羌村这一典型社区、26户常住户、146人、进行了长达三年的实践调查基础上,运用文化人类学、社会学、考古学等。

Embodied cognition: A consideration from theoretical psychology

有关具身认知思潮的理论心理学思考