1 引言

1963年Goffman提出了污名(Stigma)这个概念, 指个体所具有的不被主流文化接受的、特殊的、有缺陷的、耻辱的特征, 比如同性恋、变性人、残障人士、精神疾病患者等个体所具有的这些不同于常人的特征, 像是一种耻辱的标记, 使这些人从完美的人变成了一个有“污点”的人(Goffman, 1963; Barreto, 2015)。他人常会因这些耻辱的特征而负性地看待这类有“污点”的个体, 进而更倾向于用与这种“污点”相关的不好的、消极的特征来定义这类群体, 比如提到精神疾病患者, 很多人都会觉得他们是会打人、咬人的疯子, 但事实上并不是所有的精神疾病患者都会出现极端躁狂的症状, 还有很多患者是具有行为能力的, 像这种贴负性标签的过程就是污名化(Stigmatization) (Goffman, 1963)。污名看上去与刻板印象很相似, 但刻板印象也可能包含积极的成分, 而污名的实质则是一种消极的刻板印象, 是在一定社会背景下对某些个体或群体给予的贬低性、侮辱性的标签(张宝山, 俞国良, 2007)。而且, 对污名群体的负性刻板印象还会被当前社会背景下的主流文化群体成员认可和分享, 这也是被污名个体被广泛边缘化的原因(Major & O'brien, 2005)。

污名化的本质是一种以负性的态度看待具有特殊特征的个体, 而歧视除了用负性的态度看待被歧视对象外, 还会用负性的行为来直接对待被歧视对象(Hack et al., 2019; Major, Dovidio, & Link, 2018)。虽然污名化没有歧视行为表现得那样直接赤裸裸的负性对待, 但污名化不仅仅是给具有污名特征的个体贴了标签这样简单, 污名化对被污名个体的影响远远大于我们想象的程度。个体或群体因自己具有某种被贬低的特征使其不被主流文化群体接纳或包容, 被动地受到来自主流群体的消极态度, 隐蔽的不公平对待、侮辱、贬低, 遭受孤立、拒绝、排斥。被污名化而造成的孤立、排斥或拒绝是一种不愉快的经历, 与人类期望得到接受和归属的基本需求是相矛盾的(Pasek, 2015), 这些经历反过来会对个体或群体产生深远的消极影响。研究表明, 被污名的影响不仅与个体的心理健康、疾病有关(岳童, 王晓刚, 黄希庭, 2012), 还影响个体的社交互动, 进而导致或加剧贫穷、丧失就业机会等诸多消极后果(Major & O'brien, 2005)。

以往的研究多集中在导致个体被污名化的特征, 如种族、疾病、残疾、性取向等问题(Sanchez, Chaney, Manuel, Wilton, & Remedios, 2017), 以及主流文化群体如何消极对待污名个体, 也有一部分研究关注污名化对个体所患疾病(如精神类疾病)的影响(Ociskova, Prasko, & Sedlackova, 2013), 但较少有研究从被污名个体的角度来考察被污名的经历是如何反过来影响被污名个体的人际互动的。人际互动是个体与他人传递信息、情感交流的基本方式, 包括人际沟通、人际合作等多种人与人之间相互作用的形式(Hayes, 2002), 是个体与他人或社会建立联系的必要手段, 在人们的生活中扮演重要角色。本文将从被污名个体的角度出发, 着重介绍这种污名化对被污名个体的人际交往互动过程中产生的负性影响。

2 污名化对个体人际互动的影响

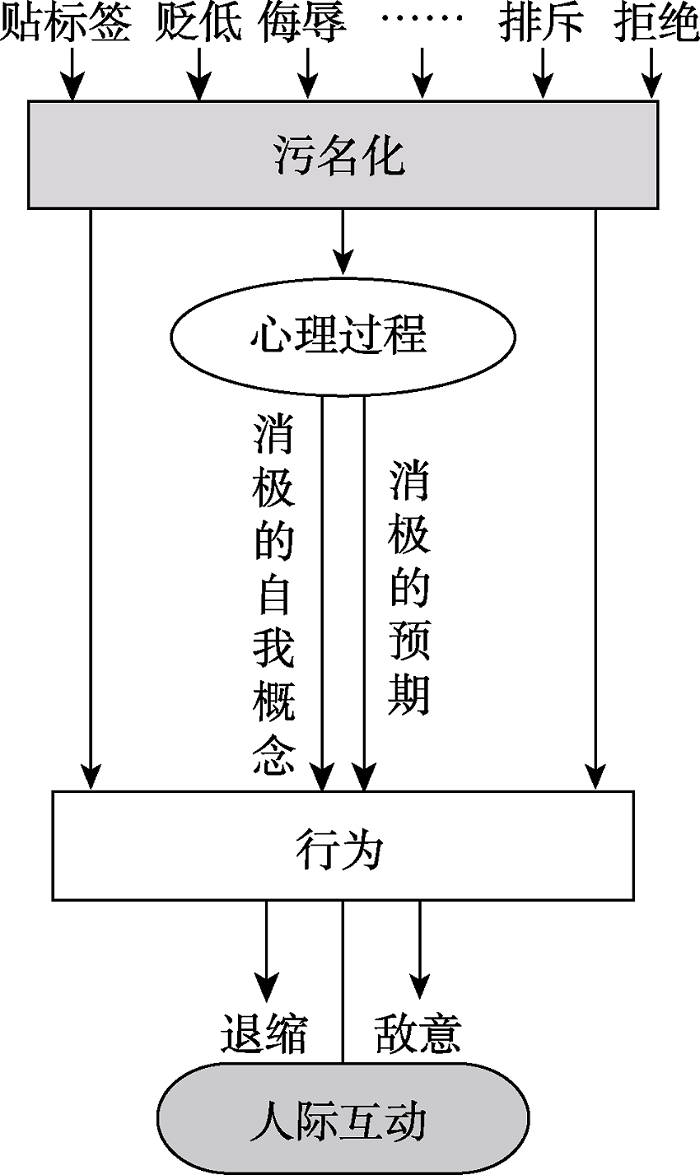

因自己的污名特征而被他人诋毁、歧视的经验, 会影响个体的自我感知和自我评价, 使个体产生消极的自我概念, 引发个体对再次被污名化的担忧, 对未来产生消极预期, 这些消极的自我概念和消极预期更容易导致在人际互动过程中的不信任、焦虑等消极情绪, 进一步导致个体在人与人的信息传递、情感交流等人际沟通等方面保持警惕、产生敌意, 并在人与人的行为互动中进一步产生回避、退缩行为。

2.1 消极自我概念

自我概念(Self-Concept)是对自己的信念的集合(金盛华, 1996; Leflot, Onghena, & Colpin, 2010), 是一个人的自我认知, 可以通过经验、反省和他人的反馈, 逐步加深对自身的了解(Myers, 2009), 而消极的自我概念往往体现在自我忽视、自责、自我憎恨等方面(Sebastian, Burnett, & Blakemore, 2008; Yengimolki, Kalantarkousheh, & Malekitabar, 2015)。自我概念与社会互动存在相关(Diswantika, 2019), 而且消极的自我概念会影响个体与他人的社会互动、社会交往。对于被污名个体而言, 即便污名特征能够被隐藏起来, 也还会对个体的心理状态产生影响。随着时间的推移, 污名相关的高社会排斥导致较低的自尊(Rice, Richardson, & Kraemer, 2014), 而且当污名个体看到他人对自己的消极刻板印象, 个体会对自己所具有的特征感到羞耻(Levin & van Laar, 2006)。那些来自他人针对污名特征的、长期的负性对待, 容易使被污名化个体将这种负性反应视为合理的现象, 这会直接影响个体的自我相关概念, 如降低的自我价值(Self-cost)和自我效能(Self-efficacy), 产生消极自我意识情感(Self-conscious emotion), 这些消极的自我认知会进一步影响个体的自我感知(Doyle & Molix, 2016; Levin & van Laar, 2006)。比如, Preciado, Johnson和Peplau (2013)的研究通过操控外界对同性行为的评价, 来考察污名化对LGBT [女同性恋者(Lesbian)、男同性恋者(Gay)、双性恋者(Bisexual)与跨性别者(Transgender)]类个体自我感知性取向的影响。研究发现, 相对于否定同性性行为的实验条件, 在支持同性性行为线索的实验条件下, 个体自我感知的性取向包含更多的同性性兴趣, 同时对同性吸引力评价更高。另外, 来自体重污名的研究也发现, 过度肥胖者常常会因自己的体重问题在伴侣关系中对自己所具有的伴侣价值(Mate Value)感知偏低(Boyes & Latner, 2009)。这些研究都发现具有污名特征的个体, 常常会因为这些特征而在许多方面对自己的价值评价偏低, 产生较低的自我感知。

污名化不仅会引发个体产生消极的自我认知、自我评价, 逐步导致个体形成消极的自我概念, 还会促使个体进一步去印证这些消极的自我概念。来自外界的消极评价会影响被污名个体的自尊/自我感知, 还可能引起基于负性评价的“自我惩罚”。Hirsch等(2019)在研究中选取了100名低收入成年人, 评估了其社会人口学特征、经济污名对健康生活质量的影响、归属感在其中的中介作用, 来考察经济污名与身体健康之间的联系以及其潜在的机制。研究结果发现经济污名和较低的归属感都会直接导致心理健康、生活质量的下降, 同时那些感到经济污名的个体无法在他们渴望的程度上进行人际交往, 从而产生自我惩罚的想法。更严重的是, 被污名化的个体会进一步印证这些消极方面。自我理论学者认为负面自我观点的人会执行某些行为以证实他们消极的自我概念(Swann, Pelham, & Krull, 1989)。例如, 由于肥胖而经历负性事件的个体会更多地在工作中退缩, 他们更倾向于采取不健康的生活方式(Araiza & Wellman, 2017)、更多地依赖医疗来应对与体重过重的问题(Lam, Huang, & Chiu, 2010)。持有消极的自我观点, 会加剧污名化对个体的负性影响。负性的污名化经历还会引起个体的自我威胁(Self-threat), 这种自我威胁更容易导致在人际互动过程中的不信任、焦虑和退缩行为(Pasek, 2015)。

2.2 消极预期

污名产生的影响, 不仅来源于他人直接的拒绝, 还来自个体被贴标签后产生内在的被拒绝的预期。个体所具有的污名特征, 会引发个体对社会排斥和受到诋毁的担忧, 导致压力增加(Stroud, Tanofsky-Kraff, Wilfley, & Salovey, 2000), 自我调节受损(Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Twenge, 2005)。这些消极的情绪感受和过往的污名化经历会导致个体对未来的消极预判, 在一些情景下个体会预感自己将成为非污名化群体歧视的目标, 如精神疾病患者经历过被污名化以后, 他们认为公众对精神疾病患者是持消极态度的, 并且他们会在后来的活动中认为公众会以歧视的方式对待他们(Brohan, Gauci, Sartorius, Thornicroft, & Group, 2011)。Blodorn, Major, Hunger和Miller (2016)的研究也证明了对被拒绝的预期可以调节体重污名对超重个体的负性影响。研究者让高体重指数(Body Mass Index, BMI)和低体重指数男女被试进行约会情境下演讲, 一半被试被告知潜在的约会对象会观看被试的演讲录像, 一半被试被告知潜在的约会对象会收听被试的演讲录音。结果发现高体重指数女性的拒绝预期导致一些负性影响, 当被告知自己的演讲录像会被观看, 高体重指数女性被试报告了较高的拒绝预期、较高的自我意识情感和压力, 以及较低的自尊水平, 而男性被试的反应并不受到体重指数或潜在约会对象观看和收听演讲方式的影响。此外, 有研究也发现一些疾病患者也存在对他人的基于疾病污名身份负性反应和态度的消极预期, 如癫痫患者(Bautista, Shapovalov, & Shoraka, 2015)、乙肝患者(Cotler et al., 2012), 进一步验证了具有污名特征的个体会因过往的被污名化的经历, 在社会互动中持有消极预期。

这种对被污名化的预期可以被称为“污名/耻辱意识(Stigma consciousness)”, 具有较高污名意识的个体, 在即使没有实际歧视的情况下也会产生被污名化的预判, 造成心理困扰, 进而破坏社交互动(Clark, Thiem, Hoover, & Habashi, 2017; Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009)。被污名化的个体持有污名意识, 这些意识容易被内化或投射到他人身上, 进而加强自己被污名化的预期(Berghe, Dewaele, Cox, & Vincke, 2010)。基于那些直接或替代的、作为歧视目标的经验, 污名群体成员之间倾向于分享他们的经历、信念、预期和潜在影响。成员之间的讨论会让他们更加意识到自己是如何被赋予消极刻板印象, 那些对歧视保持警惕的个体, 反而可能通过这种交流加剧对歧视的焦虑、处于恐惧之中, 而这些潜在的威胁和恐惧可能进一步导致个体在之后的社交活动中出现更多的焦虑(Cadaret, Hartung, Subich, & Weigold, 2017), 进而在将来可能会感知到更多的歧视(Levin & van Laar, 2006)。个体在模糊的情况下, 倾向于判定自己将会遭受到不公平的对待, 成为他人歧视的目标。这些内化的污名, 反应了个体本身接受了对其特征的消极观念, 是其压力和焦虑的真正来源(Logie, Newman, Chakrapani, & Shunmugam, 2012)。而且, 这些消极预期并非仅仅存在于意识层面, 还会引起相应的生理反应。Blascovich, Mendes, Hunter, Lickel和Kowai-Bell (2001)的研究发现, 被污名化的个体与没有被污名化的个体进行互动时会表现出与威胁相关的生理反应模式(如心血管反应性, 包括VC肺活量、CO心输出量、TPR平均动脉压等指标的显著增加或减少), 并且与没有被污名化的个体相比行为表现更差。这些与污名威胁相关的生理反应, 进一步证明污名化对于被污名个体的影响是客观存在的, 而且当被污名化个体感受到这种歧视、拒绝是普遍的、长期的, 他们会消极接受, 不会再试图努力、积极地寻求任何改善(Barreto, 2015), 导致个体长期处于消极的循环状态之中。

2.3 退缩行为

污名化还会导致个体在社会互动中的退缩行为。研究者发现基于过去被污名化的经历(如被排斥), 个体的自我效能感会降低, 导致其在之后的人际交往过程中会出现消极、退缩行为(Preciado et al., 2013)。过去令个体感到羞耻的经历会促进个体逃离人际交往, 避免与他人进行互动。一些针对疾病污名的研究发现, 具有某种易被污名化的疾病的患者, 往往都经历过内化的污名, 表现出疏离感和社交退缩(Waugh, Byrne, & Nicholas, 2014)。比如, 一些针对精神障碍患者异常行为的报道, 会给这类患者带来耻辱感。他们可能会因承认自己的疾病、或因自己接受过治疗而感受到耻辱, 害怕受到他人的嘲笑和社会拒绝, 反而使其抗拒主动寻求心理健康治疗, 并采取回避的策略退出社交互动(Boudewyns, Himelboim, Hansen, & Southwell, 2015; Oliveira, Esteves, & Carvalho, 2015)。实验室条件下也发现具有污名特征的个体在人际互动中存在退缩行为。Newheiser, Barreto, Ellemers, Derks和Scheepers (2015)为考察污名特征在人际互动中的影响, 在实验室条件下让被试与另一名对被试所具有的特征持消极态度的合作者进行互动, 被试需要在互动中隐藏自己的污名特征。未被污名被试和已被污名被试需要在: 1)避免消极印象而隐藏污名特征, 或2)促进积极印象而隐藏污名特征, 或3)单纯隐藏污名特征的实验条件下, 与合作者进行互动。结果发现, 在以避免消极印象和促进积极印象为目的而隐藏自己的特征的互动中, 被污名被试的参与度显著低于未被污名被试。因污名特征导致的退缩行为不仅出现在一般意义的社会互动中, 甚至还会发生在被污名个体与其家庭成员之间的互动中(Perlick et al., 2011), 提示因污名化而导致的退缩行为是比较广泛的。

这种社会退缩是与被污名化个体消极的污名预期有关的, 能够预期到的污名化会导致个体为避免被歧视而采取退缩行为, 消极影响个体的社交互动(Moore & Tangney, 2017)。研究者发现感知到的公众污名与寻求帮助意愿之间的关系由自我污名和态度所调节。被污名化个体对公众污名的认识促成了自我耻辱感, 这反过来影响了其寻求帮助的态度, 最终影响了求助意愿。Moore和Tangney (2017)以犯人为研究对象, 通过量表测量考察污名预期与社会退缩行为之间的关系。研究者在犯人被释放前(时间点1, 即在监狱中服刑)对污名预期进行评估, 在犯人被释放后3个月时(时间点2)评估其社会退缩行为, 在犯人被释放1年后(时间点3)对行为结果进行评估, 发现监禁时期对污名的预期可以预测出狱后的社会退缩行为, 被试在监禁期间对污名预期越多, 他们就越有可能在释放三个月后的社会互动中产生退缩并感到孤立隔离, 这种退缩还可以预测被释放一年后的心理健康问题。与消极预期相关的退缩不仅体现在人与人之间的交互过程中, 还会体现在个体的生理指标和认知功能上, 例如Allen和Friedman (2016)在研究中操作刻板印象威胁或反刻板印象威胁, 发现刻板印象威胁会导致个体产生更大的迷走神经活动退缩(vagal withdrawal), 并且在相关的任务中表现出工作记忆下降、参与程度降低, 反应了个体从生理到行为表现上的退缩。

更严重的是, 持续的污名化导致个体认为这些不公平的对待是普遍和长期的, 污名个体不会积极去追求被主流群体接纳和重新与社会建立联系(Newheiser & Barreto, 2014), 这种消极的应对方式会体现社会互动中的很多方面。比如, Richman, Martin和Guadagno (2016)的研究发现与未经历污名化的对照组被试相比, 基于污名而被拒绝的被试对笑脸的反应时间更慢, 对识别与社会联系相关的词汇成绩更低。这些结果表明, 被污名的经历导致个体对社会接受信号的检测变差, 这样的行为反应倾向可能会妨碍个体社会归属的修复和社会互动的联结。过去的经历和消极的预期, 导致人们采取保密、退缩等方式, 这些方式虽然能够暂时避免直接面对基于污名的拒绝、排斥, 但这些应对方式实际上会更进一步加剧其被孤立或其他潜在的危害。

2.4 敌意行为

污名化一般与负性情感反应有关, 污名化后个体常会经历较高的消极情绪和较低的积极情绪, 这些负性情绪反过来会进一步作用于被污名个体的人际交往活动(Krendl, Zucker, & Kensinger, 2017)。来自主流文化的歧视, 会使污名化个体意识到, 他们可能会在任何时间任何情境下都将遭受到来自主流文化群体成员的歧视和拒绝, 而且被污名群体成员与主流文化群体成员之间的互动往往是不舒服的, 常常在互动中强化了对彼此的负面看法(Levin & van Laar, 2006), 这更容易导致个体情绪焦虑(Khoshkam, Bahrami, Ahmadi, Fatehizade, & Etemadi, 2012), 并对主流群体文化产生敌意。由于污名特征, 个体常常会感知和体验到来自他人的消极反馈, 这种不断重复的经历会提高污名化个体对拒绝的敏感度(Zangl, 2013)。有报道指出基于污名特征的社会孤立是青少年暴力行为最重要的原因(Levin & van Laar, 2006), 实际上, 早期的人际关系中形成的高拒绝敏感性会持续伴随焦虑, 使个体对威胁更加警惕(Richman et al., 2016), 更容易察觉到歧视和拒绝或将模糊的人际关系解释成为歧视或拒绝, 进而反应过度, 充满敌意和攻击性地强硬应对(Bifftu & Dachew, 2014)。

污名的负性影响会使个体对未来产生负性预判进而在人际交往中采取消极应对方式, 影响人们是否进入社交互动及社交活动中的行为(Richman et al., 2016), 这些影响体现在社交互动的很多方面, 尤其体现在人际信任方面(Zhang, Barreto, & Doyle, 2019), 它是社交活动中维持互动行为持续进行关键的要素。基于被视作歧视目标的经历, 被污名个体会对他们是否面临歧视保持警惕, 这种警惕与信任他人是相冲突的(Richman et al., 2016)。Zhang等(2019)的研究中让被试回忆自己过往因污名特征而被他人拒绝的经历或在实验室条件下因污名特征而被拒绝, 然后考察被试在这之后的人际互动游戏(Coin-toss game)中的表现, 结果发现个体在回忆或经历因污名特征遭受的拒绝比因其他因素遭受到拒绝相比, 在互动游戏中表现出来更多的不信任行为。还有研究也发现基于污名的拒绝与不信任存在相关, 例如, 被医疗工作人员歧视过的患者往往对所有医疗人员都不太信任(Verhaeghe & Bracke, 2011), 而在服务行业中用户被污名的经历越多, 其报告的信任度越低, 对服务的满意度也越低。个体所持有污名特征导致其在社交活动中进行自我保护(Schmitt & Branscombe, 2002), 通常他们会对他人持有消极观点并产生敌意, 甚至伴有攻击行为, 而且这些敌意不仅仅限于对那些曾经歧视他们的人(Levin & van Laar, 2006), 也可能泛化到参与互动过程中的所有人。

综上所述, 被污名化不仅会给个体带来困扰, 使其处于消极的情绪状态, 长期的、被歧视的经历还会导致消极的自我概念, 而持续的、被再次污名的恐惧会使个体产生消极的认知和预期, 会导致产生一系列退缩、敌意敌对等消极的行为, 进一步影响个体的人际交往及社会互动(图1)。

图1

3 基于污名的应对方式

污名化对被污名个体和群体的影响是很持久的, 基于污名特征的消极体验是不会随着时间的推移而改善的(Chung, Tse, Lee, Wong, & Chan, 2019)。如果没有及时对污名化进行针对性的措施或干预, 污名感知的转变是不可能发生的(Armentor, 2017)。减少大众对具有污名特征个体的污名化固然是一个重要问题, 但在当前社会条件下, 如何帮助被污名个体应对这些污名化似乎是更紧迫的问题。面对因污名特征而受到不公平对待时, 个体可以采取一些方式或策略来应对(Bos, Koh, van Beusekom, Rothblum, & Gartrell, 2019)。

3.1 归因策略

采用将消极事件归因于歧视的策略可以缓解污名化给个体带来的消极影响。当被污名个体遇到负性事件时, 他们将这些事件归结于他人的歧视行为, 而不是自己所具有的特征, 这样个体的自尊就会被保护起来, 减少负性影响。但是, 这种归因于歧视行为的方法并不能从根本上消除污名化的消极作用, 反而会影响个体的社会属性。对于公然的歧视, 这种归因会保护个体的自尊, 但对于隐蔽的歧视实际上对个体的自尊影响还是很大的(Major & O'brien, 2005), 而且会降低个体的社会归属感(Newheiser & Barreto, 2014)。另外, 被污名群体成员减少与非污名化群体成员之间的比较竞争, 也可以在某种程度上减少因污名特征导致的负性反馈的影响。比如, 通过自我妨碍(self- handicap)来避免或减少由竞争而产生的影响。将直接比较的结果归因于外部因素(如生病、意外), 而非自己具有的某项(污名)特征, 能够避免直接的比较所带来的真实能力的评估结果, 但这种减少竞争的方式同时更可能会破坏个体的自尊(Barreto & Ellemers, 2015)。

3.2 替代性努力

污名化个体有时还会倾向于不再努力对抗他人的负性评价或观点, 而是通过强化自己其他方面来减少污名化的负性效应, 即采取替代性努力的策略。这种应对策略比较常见于一些与性别刻板印象有关的比较中, 如在考试中女性被试倾向于较少回答与数学相关的问题, 而专注于回答与语言能力相关的问题, 这实际上是采取消极对待方式来默认这种刻板印象(Finnegan, Oakhill, & Garnham, 2015)。通常, 个体会认为在这个被别人否认的领域他们自己的表现已经不再重要, 而倾向于更加努力去通过其他方面来“弥补不足”。

同时, 在个体在面临威胁性环境时, 采用自我肯定干预(Self-affirmation intervention)也是很有效的手段。自我肯定理论(Self-affirmation theory)认为当个人遇到心理威胁的情况或发现自己处于威胁的环境中时, 就会启动自我保护系统(Steele, 1988), 对自己积极的看法、肯定自己的价值, 能够有效缓解社会排斥、歧视导致的个体自尊心下降(Meng, 2020)。自我肯定干预(Self-affirmation intervention)为个体提供了确立其核心价值观的机会(Cohen & Sherman, 2014), 是恢复自我完整性的最有效方法之一(Thomas, 2018), 进一步帮助个体应对污名化带来的消极影响。

3.3 提高群体认同

被污名化的个体可以通过接近具有相同污名特征的群体以共同面对这些威胁。这样的群体可以提高归属感, 提供情感、信息等方面的支持, 能够减少偏见对个体自尊方面的负性影响。高群体认同感的个体可以通过提高自己对所在群体的认同来减少外界歧视对自己的影响, 而低群体认同感的个体则通过减少群体认同感或通过默认的方式来减少歧视对自尊的影响(Ellemers, 2018; Matthews, Dwyer, & Snoek, 2017)。有研究者采用种族歧视相关的阅读材料来考察污名化对拉美裔学生的影响, 发现在读完对其种族群体的普遍偏见的文章后, 之前报告民族群体认同感较低的拉美裔学生对其群体认同感更低, 而之前报告民族群体认同感较高的拉美裔学生对其群体认同感更高(McCoy & Major, 2003), 揭示了污名化对群体认同感的影响在高认同感个体和低认同感个体作用的分离。还有研究采用对不同类型潜在约会对象(吃薄荷vs吃大蒜、黑人vs白人、性别歧视者vs非性别歧视者)进行评估的方法, 来考察污名化过程中群体身份的重要性和自我保护性认知的作用, 发现当被污名的特征是群体身份的基础时, 个体的自我保护认知就会发挥作用(Crandall, Tsang, Harvey, & Britt, 2000)。这些研究说明, 提高群体认同在某种情境下, 能够帮助个体较好地应对污名化。

另外, 鉴于社交媒体在当代人的生活中扮演者重要的角色, 被污名个体也可以求助于流行的社交媒体, 分享他们的疾病经历或向其他有类似健康状况的人寻求建议, 来获得心理和身体健康的干预措施。事实上, 具有污名身份的个体对自身所具有的污名化身份的表达, 在整体上会产生积极效果(Sabat et al., 2019)。精神疾病的患者就可以通过与同龄患者的在线互动(Naslund, Aschbrenner, Marsch, & Bartels, 2016), 彼此分享自己的故事和应对被歧视的策略, 为他们提供更深厚的社会联系、群体归属感以及更低的污名感知。

3.4 接触干预

虽然当前社会人们整体心理健康知识有所提高, 但很多人仍会对被污名群体持消极态度。简单地宣传、教育可能不是减少污名化的最有效途径, 还需要更加有效的实践措施(Li et al., 2018a), 接触干预可能是减少公众污名的重要方式之一。目前, 不同形式的接触已被应用在减少公众污名的干预研究中, 并且发现在态度、情感、行为倾向等方面均能比较有效地减少污名影响(赵鹤宾 等, 2019)。还有研究者开发了综合干预措施(反污名和歧视策略、心理教育、社会技能训练和认知行为治疗), 用以干预污名化对精神分裂症患者的临床症状、社会功能、内在污名体验和歧视的影响(Li et al., 2018b), 实践证明这种干预措施可以有效地减少精神分裂症患者的消极预期, 提高克服污名的技能, 改善临床症状和社会功能。这些接触干预的方式也具有一定的局限性, 对某些类型的污名群体比较有效(如轻度精神疾病患者, 同性恋群体), 但可能对一些类型的污名群体难以达到相似的作用(如HIV携带者)。

以上较常见的污名应对方式, 从不同的层面、作用于不同的心理过程而起到减少污名影响的作用。归因策略和提高群体认同, 主要作用于个体的认知层面, 从自身认知的角度减少污名给个体带来的负性效应。而替代性努力和接触干预策略更多的是从外在行为反应层面上, 获取更多的、外在的积极反馈, 进而减少污名化带来的影响。

然而, 正如污名化是存在于特定的社会文化背景中, 上述常用的应对策略也会受到社会文化的调节和影响(Yang et al., 2007), 不同文化背景下被污名个体存在应对策略的选择偏好。在一些文化背景下, 向周围的人表明自己的污名特征, 很可能会得到更多的支持, 减少公然被歧视的可能(Barreto, 2015)。比如在英国, 同性恋婚姻已经合法, 在这种环境下, 同性恋群体更倾向于采取暴露污名特征的策略, 公开表明自己的情况能够减少被污名的可能。与之相反, 在一些文化下, 同性恋婚姻不合法, 公开污名特征则会导致被污名化甚至遭受暴力对待的几率增加。不同文化背景很可能会间接导致或加剧具有某些污名特质的个体受到不公平待遇(Yang, 2007)。以亚洲的集体主义文化为例, 这种文化强调情感抑制、避免羞耻和保存面子(Shea & Yeh, 2008), 在这样的文化背景下, 被污名个体不愿意去主动暴露自己的污名特征, 更倾向于采用隐蔽的策略或在其他方面的替代性努力来避免或减少被歧视的可能性。污名应对策略也具有一定的局限性, 不仅受到传统文化的影响, 还受到社会制度的制约。以精神疾病为例, 如果在某种社会制度下, 政府机构会为这类疾病的患者建设完善的医疗服务体系、提供健全的救治服务, 那么不仅会对这类患者病情的好转带来益处, 还会降低这类患者受到公然的社会歧视的可能性, 被污名个体将更容易采用接触干预的方式来减少污名化的影响。

4 小结与研究展望

尽管污名研究越来越受到人们的关注, 以往研究者也提出了许多基于不同理论取向的污名化应对策略, 如问题聚焦性与情绪聚焦性策略、卷入与摆脱策略等(杨柳, 刘力, 2008; 杨柳, 刘力, 吴海铮, 2010), 但针对污名化对个体人际互动影响的研究和相应的应对策略, 仍在许多方面有待进一步探索。

第一, 缺乏评估污名化对人际互动影响的测评工具。人们都能够意识到被污名和歧视对个体的行为有许多负性影响, 如何有效地通过自我报告和行为测试来量化这些影响, 还有待于进一步探讨。目前有一些量表, 如与耻辱相关的排斥量表(Stigma-Related Rejection Scale, SRS) (Luoma et al., 2007)、慢性疼痛内化污名量表(Internalized Stigma of Chronic Pain Scale, ISCPS) (Waugh et al., 2014)、(家庭)成员污名量表(Affiliate Stigma Scale, ASS) (Chang, Su, & Lin, 2016)、医生职业压力污名量表(Stigma of Occupational Stress Scale for Doctors, SOSS-D) (Clough, Ireland, & March, 2019)、残疾障碍应对量表(Coping with Disability Difficulties Scale, CDDS) (Pérez-Garín, Recio, Silván-Ferrero, Nouvilas, & Fuster-Ruiz de Apodaca, 2020)等虽然含有感知的污名化如何影响人际互动的相关条目, 但这些类似的量表仅仅反应出个体对自己所受到的不公平对待的感知, 并不能量化这些负性影响对行为方式上造成的改变, 所以目前还缺乏更加详细的、系统的评估污名化对人际互动影响的针对性测评工具。将污名化对人际互动影响的测评工具与其他心理健康的测量工具相结合, 共同评估个体当前的心理和行为健康水平, 可以更加客观反应被污名化个体或群体受到污名影响的程度, 更重要的是能够提示是否需要进一步采取措施进行心理干预。

第二, 缺乏研究深入探讨污名化产生的消极影响的来源。我们在很多研究中都能够看到污名化对于被污名个体产生了很多的消极影响, 但是对于这些消极影响的来源还存在很多争议。被污名个体面对污名化时所伴随的相应的消极应对方式, 很可能源于个体对污名化的归因偏差(Attribution bias), 即被污名个体在评估他人对待自己这种方式的原因时将其归因为自己所具有的“羞耻”的特征, 而不是他人的偏见, 而陷入深深的自我污名和自我否定中(Mak & Wu, 2006), 或者归因于外界对待自己就是不友好的, 先入为主地认为自己会受到不公平的待遇(Armstrong & Brandon, 2019), 这两种情况都会导致个体陷入消极、防御的状态, 产生消极的人际互动。另外, 探讨污名化产生消极影响来源的一个重要方面是对其“追本溯源”, 即探讨污名化产生的社会根源及文化根源。污名化存在于特定的社会文化背景中, 不同的文化背景能够决定某种特征是否会被污名或者是否导致个体因其污名受到歧视(Yang, 2007)。从污名化发生根源对其进行探讨, 有助于探索针对性的措施从根本上“消除”污名化的消极影响。

第三, 缺乏深入探讨污名化对个体人际互动消极影响的神经机制方面的研究。污名化给被污名个体带来的影响和痛苦, 并非无病呻吟, 很可能存在一定神经生理基础。虽然有研究发现双侧杏仁核和双侧下额叶前皮质对污名化线索比较敏感(Krendl et al., 2006; Krendl, Heatherton, & Kensinger, 2009), 但这些研究是从非污名群体的角度出发, 考察非污名群体如何看待污名。也有研究发现源于他人或社会群体而引起的“社会性疼痛(Social pain)”会产生与躯体生理疼痛相似的效果或反应, 这种社会性疼痛和躯体疼痛在某种程度上依赖于相同的功能系统或神经回路, 如与躯体疼痛密切相关的背侧前扣带皮层(dACC)在个体经历社会排斥时也会被显著激活(Owens et al., 2017)。基于这些内在的联系, 让我们有理由猜测, 污名化对个体人际互动的影响也可能是基于一些神经功能的改变而体现于外的表现。对于具有明显污名特征的群体而言, 污名化是引起这类群体社会性疼痛的主要来源。深入探讨这些神经机制问题, 有助于探讨社会性疼痛的心理及神经机制, 为我们理解被污名个体的心理过程提供重要启示, 进而会帮助被污名个体有效地、有针对性地选择和采取措施, 从根本上改善污名化对个体社会互动的消极影响。

参考文献

Threatening the heart and mind of gender stereotypes: Can imagined contact influence the physiology of stereotype threat?

Weight stigma predicts inhibitory control and food selection in response to the salience of weight discrimination

Living with a contested, stigmatized illness: Experiences of managing relationships among women with fibromyalgia

DOI:10.1177/1049732315620160

URL

PMID:26667880

[本文引用: 1]

This study focuses on the negotiation of relationships among women living with the chronic illness fibromyalgia. Twenty in-depth, semistructured interviews were conducted with women diagnosed with fibromyalgia. Drawing from interactional and constructionist perspectives, the analysis focuses on participants' approaches to communicating with others about their illness, the reactions of others to their experiences, and participants' strategies to manage stigma. Participants attempted to describe their illness experience to others through direct and educational approaches. Often, in the management of their relationships with close family and friends, there was an unspoken awareness of illness effects, and social support was offered. However, disbelief and a lack of understanding often led participants to avoid social interactions in the attempt to hide from the stigma associated with an invisible and contested illness.

Mental distress and “self- stigma” in the context of support provision: Exploring attributions of self-stigma as sanism

Experiencing and coping with social stigma

Chapter three: Detecting and experiencing prejudice: New answers to old questions

Social exclusion impairs self-regulation

Factors associated with increased felt stigma among individuals with epilepsy

Minority‐specific determinants of mental well‐being among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth

Perceived stigma and associated factors among people with schizophrenia at Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional institution based study

Perceiver threat in social interactions with stigmatized others

Unpacking the psychological weight of weight stigma: A rejection-expectation pathway

Meaning in life as a moderator between homophobic stigmatization and coping styles in adult offspring from planned lesbian-parent families

DOI:10.1007/s13178-012-0104-3

URL

PMID:23565067

[本文引用: 1]

Certain research topics - including studies of sexual behavior, substance use, and HIV risk -- are more likely to be scrutinized by the media and groups opposed to this area of research. When studying topics that others might deem controversial, it is critical that researchers anticipate potential negative media events prior to their occurrence. By developing an Emergency Public Relations Protocol at the genesis of a study, researchers can identify and plan for events that might result in higher scrutiny. For each identified risk, a good protocol details procedures to enact before, during and after a media event. This manuscript offers recommendations for developing a protocol based on both Situational Crisis Communication Theory and our experience as an HIV prevention research group who recently experienced such an event. The need to have procedures in place to monitor and address social media is highlighted.

Stigma’s effect on social interaction and social media activity

Weight stigma in existing romantic relationships

Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with bipolar disorder or depression in 13 European countries: The GAMIAN- Europe study

DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.001

URL

PMID:20888050

[本文引用: 1]

BACKGROUND: There is little information on the degree to which self-stigma is experienced by individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or depression across Europe. This study describes the levels of self-stigma, stigma resistance, empowerment and perceived discrimination reported in these groups. METHODS: Data were collected from 1182 people with bipolar disorder or depression using a mail survey with members of national mental health non-governmental organisations. RESULTS: Over one fifth of the participants (21.7%) reported moderate or high levels of self-stigma, 59.7% moderate or high stigma resistance, 63% moderate or high empowerment, and 71.6% moderate or high perceived discrimination. In a reduced multivariate model 27% of the variance in self-stigma scores, among people with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or depression, was accounted for by levels of empowerment, perceived discrimination, number of areas of social contact, education and employment. LIMITATIONS: Findings are limited by the use of an unweighted sample of members of mental health charity organisations which may be unrepresentative of the reference population. CONCLUSIONS: These findings suggest that self-stigma occurs among approximately 1 in 5 people with bipolar disorder or depression in Europe. The tailoring of interventions to counteract (or fight against) the elements of self-stigma which are most problematic for the group, be they alienation, stereotype endorsement, social withdrawal or discrimination experience, may confer benefit to people with such disorders.

Stereotype threat as a barrier to women entering engineering careers

Using the Affiliate Stigma Scale with caregivers of people with dementia: Psychometric evaluation

Experience of stigma among mental health service users in Hong Kong: Are there changes between 2001 and 2017?

Gender stereotypes and intellectual performance: Stigma consciousness as a buffer against stereotype validation

Development of the SOSS-D: A scale to measure stigma of occupational stress and burnout in medical doctors

The psychology of change: Self-affirmation and social psychological intervention

Characterizing hepatitis B stigma in Chinese immigrants

Group identity‐based self‐protective strategies: The stigma of race, gender, and garlic

Relationship of self concepts with social interaction of students in high schools

In M. Zaim & M. Hum (Chair),

Disparities in social health by sexual orientation and the etiologic role of self-reported discrimination

DOI:10.1007/s10508-015-0639-5

URL

PMID:26566900

[本文引用: 1]

Some past work indicates that sexual minorities may experience impairments in social health, or the perceived and actual availability and quality of one's social relationships, relative to heterosexuals; however, research has been limited in many ways. Furthermore, it is important to investigate etiological factors that may be associated with these disparities, such as self-reported discrimination. The current work tested whether sexual minority adults in the United States reported less positive social health (i.e., loneliness, friendship strain, familial strain, and social capital) relative to heterosexuals and whether self-reported discrimination accounted for these disparities. Participants for the current study (N = 579) were recruited via Amazon's Mechanical Turk, including 365 self-identified heterosexuals (105 women) and 214 sexual minorities (103 women). Consistent with hypotheses, sexual minorities reported impaired social health relative to heterosexuals, with divergent patterns emerging by sexual orientation subgroup (which were generally consistent across sexes). Additionally, self-reported discrimination accounted for disparities across three of four indicators of social health. These findings suggest that sexual minorities may face obstacles related to prejudice and discrimination that impair the functioning of their relationships and overall social health. Moreover, because social health is closely related to psychological and physical health, remediating disparities in social relationships may be necessary to address other health disparities based upon sexual orientation. Expanding upon these results, implications for efforts to build resilience among sexual minorities are discussed.

Counter- stereotypical pictures as a strategy for overcoming spontaneous gender stereotypes

DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01291

URL

PMID:26379606

[本文引用: 1]

The present research investigated the use of counter-stereotypical pictures as a strategy for overcoming spontaneous gender stereotypes when certain social role nouns and professional terms are read. Across two experiments, participants completed a judgment task in which they were presented with word pairs comprised of a role noun with a stereotypical gender bias (e.g., beautician) and a kinship term with definitional gender (e.g., brother). Their task was to quickly decide whether or not both terms could refer to one person. In each experiment they completed two blocks of such judgment trials separated by a training session in which they were presented with pictures of people working in gender counter-stereotypical (Experiment 1) or gender stereotypical roles (Experiment 2). To ensure participants were focused on the pictures, they were also required to answer four questions on each one relating to the character's leisure activities, earnings, job satisfaction, and personal life. Accuracy of judgments to stereotype incongruent pairings was found to improve significantly across blocks when participants were exposed to counter-stereotype images (9.87%) as opposed to stereotypical images (0.12%), while response times decreased significantly across blocks in both studies. It is concluded that exposure to counter-stereotypical pictures is a valuable strategy for overcoming spontaneous gender stereotype biases in the short term.

Stigma and discrimination as correlates of mental health treatment engagement among adults with serious mental illness

Perceived stigma and health-related quality of life in the working uninsured: Does thwarted belongingness play a role?

DOI:10.1037/sah0000116 URL [本文引用: 1]

Attachment style and rejection sensitivity: The mediating effect of self-esteem and worry among Iranian college students

Aging minds and twisting attitudes: An fMRI investigation of age differences in inhibiting prejudice

The good, the bad, and the ugly: An fMRI investigation of the functional anatomic correlates of stigma

Examining the effects of emotion regulation on the ERP response to highly negative social stigmas

DOI:10.1080/17470919.2016.1166155

URL

PMID:26982459

[本文引用: 1]

In order to determine if highly negative stigma is a more salient cue than other negative emotional, non-stigmatized cues, participants underwent electroencephalography while passively viewing or actively regulating their emotional response to images of highly negative stigmatized (e.g., homeless individuals, substance abusers) or highly negative non-stigmatized (e.g., a man holding a gun, an injured person) individuals. Event-related potential (ERP) analyses focused on the N2 (associated with detecting novelty), the early positive potential (associated with processing emotion), and a sustained late positive potential (associated with modulating regulatory goals). A salience effect for highly negative stigma was revealed in the early positive potential, with higher magnitude ERP responses to images of highly negative stigmatized as compared to highly negative non-stigmatized individuals 355 ms poststimulus onset. Moreover, the amplitude of this effect was predicted by individual differences in implicit bias. Our results also demonstrated that the late positivity response was not modulated by regulatory goals (passively view versus to reappraise) for images of highly negative stigmatized individuals, but was for images of highly negative, non-stigmatized individuals (replicating previous findings). Our findings suggest that the neural response to highly negative stigma is salient and rigid.

Mind over body? The combined effect of objective body weight, perceived body weight, and gender on illness-related absenteeism

Teacher-child interactions: Relations with children's self-concept in second grade

Community-based comprehensive intervention for people with schizophrenia in Guangzhou, China: Effects on clinical symptoms, social functioning, internalized stigma and discrimination

Evaluation of attitudes and knowledge toward mental disorders in a sample of the Chinese population using a web-based approach

DOI:10.1186/s12888-018-1949-7

URL

PMID:30453932

[本文引用: 1]

Adapting the minority stress model: Associations between gender non-conformity stigma, HIV-related stigma and depression among men who have sex with men in South India

DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.008

URL

PMID:22401646

[本文引用: 1]

Marginalization and stigmatization heighten the vulnerability of sexual minorities to inequitable mental health outcomes. There is a dearth of information regarding stigma and mental health among men who have sex with men (MSM) in India. We adapted Meyer's minority stress model to explore associations between stigma and depression among MSM in South India. The study objective was to examine the influence of sexual stigma, gender non-conformity stigma (GNS) and HIV-related stigma (HIV-S) on depression among MSM in South India. A cross-sectional survey was administered to MSM in urban (Chennai) (n=100) and semi-urban (Kumbakonam) (n=100) locations in Tamil Nadu. The majority of participants reported moderate/severe depression scores. Participants in Chennai reported significantly higher levels of GNS, social support and resilient coping, and lower levels of HIV-S and depression, than participants in Kumbakonam. Hierarchical block regression analyses were conducted to measure associations between independent (GNS, HIV-S), moderator (social support, resilient coping) and dependent (depression) variables. Sexual stigma was not included in regression analyses due to multicollinearity with GNS. The first regression analyses assessed associations between depression and stigma subtypes. In Chennai, perceived GNS was associated with depression; in Kumbakonam enacted/perceived GNS and vicarious HIV-S were associated with depression. In the moderation analyses, overall GNS and HIV-S scores (subtypes combined) accounted for a significant amount of variability in depression in both locations, although HIV-S was only a significant predictor in Kumbakonam. Social support and resilient coping were associated with lower depression but did not moderate the influence of HIV-S or GNS on depression. Differences in stigma, coping, social support and depression between locations highlight the salience of considering geographical context in stigma analyses. Associations between HIV-S and depression among HIV-negative MSM emphasize the significance of symbolic stigma. Findings may inform multi-level stigma reduction and health promotion interventions with MSM in South India.

An investigation of stigma in individuals receiving treatment for substance abuse

The social psychology of stigma

DOI:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137

URL

PMID:15709941

[本文引用: 3]

This chapter addresses the psychological effects of social stigma. Stigma directly affects the stigmatized via mechanisms of discrimination, expectancy confirmation, and automatic stereotype activation, and indirectly via threats to personal and social identity. We review and organize recent theory and empirical research within an identity threat model of stigma. This model posits that situational cues, collective representations of one's stigma status, and personal beliefs and motives shape appraisals of the significance of stigma-relevant situations for well-being. Identity threat results when stigma-relevant stressors are appraised as potentially harmful to one's social identity and as exceeding one's coping resources. Identity threat creates involuntary stress responses and motivates attempts at threat reduction through coping strategies. Stress responses and coping efforts affect important outcomes such as self-esteem, academic achievement, and health. Identity threat perspectives help to explain the tremendous variability across people, groups, and situations in responses to stigma.

Cognitive insight and causal attribution in the development of self-stigma among individuals with schizophrenia

Stigma and self-stigma in addiction

DOI:10.1007/s11673-017-9784-y

URL

PMID:28470503

[本文引用: 1]

Addictions are commonly accompanied by a sense of shame or self-stigmatization. Self-stigmatization results from public stigmatization in a process leading to the internalization of the social opprobrium attaching to the negative stereotypes associated with addiction. We offer an account of how this process works in terms of a range of looping effects, and this leads to our main claim that for a significant range of cases public stigma figures in the social construction of addiction. This rests on a social constructivist account in which those affected by public stigmatization internalize its norms. Stigma figures as part-constituent of the dynamic process in which addiction is formed. Our thesis is partly theoretical, partly empirical, as we source our claims about the process of internalization from interviews with people in treatment for substance use problems.

Group identification moderates emotional responses to perceived prejudice

The psychological mechanism of the influence of social exclusion on risk-taking behavior

Managing the concealable stigma of criminal justice system involvement: A longitudinal examination of anticipated stigma, social withdrawal, and post-release adjustment

The future of mental health care: Peer-to-peer support and social media

DOI:10.1017/S2045796015001067

URL

PMID:26744309

[本文引用: 1]

AIMS: People with serious mental illness are increasingly turning to popular social media, including Facebook, Twitter or YouTube, to share their illness experiences or seek advice from others with similar health conditions. This emerging form of unsolicited communication among self-forming online communities of patients and individuals with diverse health concerns is referred to as peer-to-peer support. We offer a perspective on how online peer-to-peer connections among people with serious mental illness could advance efforts to promote mental and physical wellbeing in this group. METHODS: In this commentary, we take the perspective that when an individual with serious mental illness decides to connect with similar others online it represents a critical point in their illness experience. We propose a conceptual model to illustrate how online peer-to-peer connections may afford opportunities for individuals with serious mental illness to challenge stigma, increase consumer activation and access online interventions for mental and physical wellbeing. RESULTS: People with serious mental illness report benefits from interacting with peers online from greater social connectedness, feelings of group belonging and by sharing personal stories and strategies for coping with day-to-day challenges of living with a mental illness. Within online communities, individuals with serious mental illness could challenge stigma through personal empowerment and providing hope. By learning from peers online, these individuals may gain insight about important health care decisions, which could promote mental health care seeking behaviours. These individuals could also access interventions for mental and physical wellbeing delivered through social media that could incorporate mutual support between peers, help promote treatment engagement and reach a wider demographic. Unforeseen risks may include exposure to misleading information, facing hostile or derogatory comments from others, or feeling more uncertain about one's health condition. However, given the evidence to date, the benefits of online peer-to-peer support appear to outweigh the potential risks. CONCLUSION: Future research must explore these opportunities to support and empower people with serious mental illness through online peer networks while carefully considering potential risks that may arise from online peer-to-peer interactions. Efforts will also need to address methodological challenges in the form of evaluating interventions delivered through social media and collecting objective mental and physical health outcome measures online. A key challenge will be to determine whether skills learned from peers in online networks translate into tangible and meaningful improvements in recovery, employment, or mental and physical wellbeing in the offline world.

Hidden costs of hiding stigma: Ironic interpersonal consequences of concealing a stigmatized identity in social interactions

Regulatory focus moderates the social performance of individuals who conceal a stigmatized identity

Stigma and self-stigma in patients with anxiety disorders

Clinical profiles of stigma experiences, self-esteem and social relationships among people with schizophrenia, depressive, and bipolar disorders

DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.047

URL

PMID:26208983

[本文引用: 1]

Some mental illnesses and certain mental health care environments can be severely stigmatizing, which seems to be related to decreased self-esteem and a deterioration of the quality of social relationships for people with mental illness. This study aims to identify clinical profiles characterized by clinical diagnoses more strongly associated with the treatment settings and related to internalized stigma, self-esteem and satisfaction with social relationships. It also aimed to analyze associations between clinical profiles and socio-demographic indicators. Multiple correspondence analysis and cluster analysis were performed on a sample of 261 individuals with schizophrenia and mood disorders, from hospital-based and community-based facilities. MCA showed four distinct clinical profiles allowing a differentiation among levels of: internalized stigma, social relationship satisfaction and self-esteem. Overall, results revealed that internalized stigma remains a pervasive problem for some people with schizophrenia and mood disorders. Particularly, internalized stigma and social relationships dissatisfaction and associated socio-demographic indicators appear to be a risk factor for social isolation for individuals with schizophrenia, which may worsen the course of the disorder. Our findings highlight the importance to develop structured interventions aimed to reduce internalized stigma, and exclusion of those who suffer the loss of their social roles and networks.

The impact of disease- specific internalized stigma on depressive symptoms, pain catastrophizing, pain interference, and alcohol use in people living with HIV and chronic pain (PLWH-CP)

In our own voice-family companion: Reducing self-stigma of family members of persons with serious mental illness

DOI:10.1176/appi.ps.001222011

URL

PMID:22193793

[本文引用: 1]

OBJECTIVE: This article reports preliminary findings from a novel, family peer-based intervention designed to reduce self-stigma among family members of people with serious mental illness. METHODS: A total of 158 primary caregivers of patients with schizophrenia were recruited from a large urban mental health facility (93 caregivers) or from a family and consumer advocacy organization (65 caregivers). Caregivers (N=122) who reported they perceived at least a moderate level of mental illness-related stigma were evaluated on measures of self-stigma, withdrawal, secrecy, anxiety, and social comparison and randomly assigned to receive one of two, one-session group interventions: a peer-led intervention (In Our Own Voice-Family Companion [IOOV-FC]) designed to stimulate group discussion or a clinician-led family education session, which delivered information about mental illness in a structured, didactic format. IOOV-FC consisted of playing a videotape of family members who describe their experiences coping with stigma, which was followed by a discussion led by two family peers who modeled sharing their own experiences and facilitated group sharing. RESULTS: Of 24 family members and ten consumers, 96% rated the videotape above a predetermined acceptability threshold on a 19-item scale assessing cultural sensitivity, respect for different stakeholders, relevance of content, and technical quality (alpha=.92). Caregivers receiving IOOV-FC with low to moderate pretreatment anxiety reported a substantial reduction in self-stigma (effect size=.50) relative to those receiving clinician-led family education (p=.017) as well as significant reductions in secrecy (p=.031). CONCLUSIONS: Peer-led group interventions may be more effective in reducing family self-stigma than clinician-led education, at least for persons reporting experiencing low to moderate anxiety levels on a standard questionnaire

How to cope with disabilities: Development and psychometric properties of the Coping with Disability Difficulties Scale (CDDS)

DOI:10.1037/rep0000293

URL

PMID:31647269

[本文引用: 1]

PURPOSE/OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to develop and test the psychometric properties of the Coping With Disability Difficulties Scale (CDDS), a scale to measure the coping strategies used by people with disabilities to face the disability-related difficulties (caused by both disability itself and by stigma) they encounter in their daily lives. METHOD/DESIGN: An initial pool of 110 items was developed based on previous literature and the results of a qualitative study using semistructured interviews. The psychometric characteristics of the CDDS were examined in 3 samples of people with disabilities (each of which included participants with physical, visual, and hearing impairments; total N = 590). RESULTS: A final scale of 17 items was obtained. The factor structure of the CDDS was tested and replicated with an adequate fit (root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.056; goodness-of-fit index [GFI] = 0.98; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.98) using confirmatory factor analysis. The internal consistency of the 4 factors (positive thinking, social sensitization and support, adaptation, and avoidance) was adequate to excellent (with alphas ranging from .68 to .86). CONCLUSIONS/IMPLICATIONS: To the authors' knowledge, this is the first coping scale that is specifically designed for people with disabilities, and it can be highly useful for both research and applied purposes. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2020 APA, all rights reserved).

The impact of cues of stigma and support on self-perceived sexual orientation among heterosexually identified men and women

DOI:10.1016/j.jesp.2013.01.006 URL [本文引用: 2]

Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health

DOI:10.1037/a0015815

URL

PMID:19785483

[本文引用: 1]

The current research provides a framework for understanding how concealable stigmatized identities impact people's psychological well-being and health. The authors hypothesize that increased anticipated stigma, greater centrality of the stigmatized identity to the self, increased salience of the identity, and possession of a stigma that is more strongly culturally devalued all predict heightened psychological distress. In Study 1, the hypotheses were supported with a sample of 300 participants who possessed 13 different concealable stigmatized identities. Analyses comparing people with an associative stigma to those with a personal stigma showed that people with an associative stigma report less distress and that this difference is fully mediated by decreased anticipated stigma, centrality, and salience. Study 2 sought to replicate the findings of Study 1 with a sample of 235 participants possessing concealable stigmatized identities and to extend the model to predicting health outcomes. Structural equation modeling showed that anticipated stigma and cultural stigma were directly related to self-reported health outcomes. Discussion centers on understanding the implications of intraindividual processes (anticipated stigma, identity centrality, and identity salience) and an external process (cultural devaluation of stigmatized identities) for mental and physical health among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity.

Emotion mediates distrust of persons with mental illnesses

Stigma- based rejection and the detection of signs of acceptance

Stigma expression outcomes and boundary conditions: A meta- analysis

Stigma by prejudice transfer: Racism threatens white women and sexism threatens men of color

The internal and external causal loci of attributions to prejudice

Development of the self-concept during adolescence

DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.008

URL

PMID:18805040

[本文引用: 1]

Adolescence is a period of life in which the sense of 'self' changes profoundly. Here, we review recent behavioural and neuroimaging studies on adolescent development of the self-concept. These studies have shown that adolescence is an important developmental period for the self and its supporting neural structures. Recent neuroimaging research has demonstrated that activity in brain regions associated with self-processing, including the medial prefrontal cortex, changes between early adolescence and adulthood. These studies indicate that neurocognitive development might contribute to behavioural phenomena characteristic of adolescence, such as heightened self-consciousness and susceptibility to peer influence. We attempt to integrate this recent neurocognitive research on adolescence with findings from developmental and social psychology.

Asian American students’ cultural values, stigma, and relational self-construal: Correlates of attitudes toward professional help seeking

The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self

The Yale interpersonal stressor (YIPS): Affective, physiological, and behavioral responses to a novel interpersonal rejection paradigm

DOI:10.1007/BF02895115

URL

PMID:11126465

[本文引用: 1]

Given links between interpersonal functioning and health as well as the dearth of truly interpersonal laboratory stressors, we present a live rejection paradigm, the Yale Interpersonal Stressor (YIPS), and examine its effects on mood, eating behavior, blood pressure, and cortisol in two experiments. The YIPS involves one or more interaction(s) between the participant and two same-sex confederates in which the participant is made to feel excluded and isolated. In Experiment 1, 50 female undergraduates were randomly assigned to the YIPS or a control condition. Participants in the YIPS condition experienced greater negative affect and less positive affect than did those in the control condition. Further, restrained eaters ate more following the YIPS than did nonrestrained eaters. In Experiment 2, 25 male and female undergraduates completed the YIPS. The YIPS induced significant increases in tension, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) from baseline, while significantly decreasing positive affect. The YIPS appeared particularly relevant for women, resulting in significantly greater increases in cortisol and SBP for women compared to men. The YIPS, then, provides an alternative to traditional, achievement-oriented laboratory stressors and may allow for the identification of individuals most vulnerable to interpersonal stress.

Agreeable fancy or disagreeable truth? Reconciling self-enhancement and self-verification

DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.57.5.782

URL

PMID:2810025

[本文引用: 1]

Three studies asked why people sometimes seek positive feedback (self-enhance) and sometimes seek subjectively accurate feedback (self-verify). Consistent with self-enhancement theory, people with low self-esteem as well as those with high self-esteem indicated that they preferred feedback pertaining to their positive rather than negative self-views. Consistent with self-verification theory, the very people who sought favorable feedback pertaining to their positive self-conceptions sought unfavorable feedback pertaining to their negative self-views, regardless of their level of global self-esteem. Apparently, although all people prefer to seek feedback regarding their positive self-views, when they seek feedback regarding their negative self-views, they seek unfavorable feedback. Whether people self-enhance or self-verify thus seems to be determined by the positivity of the relevant self-conceptions rather than their level of self-esteem or the type of person they are.

Stigma and trust among mental health service users

Internalized stigma in people living with chronic pain

Application of mental illness stigma theory to Chinese societies: Synthesis and new direction

Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory

DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013

URL

PMID:17188411

[本文引用: 1]

Definitions and theoretical models of the stigma construct have gradually progressed from an individualistic focus towards an emphasis on stigma's social aspects. Building on other theorists' notions of stigma as a social, interpretive, or cultural process, this paper introduces the notion of stigma as an essentially moral issue in which stigmatized conditions threaten what is at stake for sufferers. The concept of moral experience, or what is most at stake for actors in a local social world, provides a new interpretive lens by which to understand the behaviors of both the stigmatized and stigmatizers, for it allows an examination of both as living with regard to what really matters and what is threatened. We hypothesize that stigma exerts its core effects by threatening the loss or diminution of what is most at stake, or by actually diminishing or destroying that lived value. We utilize two case examples of stigma--mental illness in China and first-onset schizophrenia patients in the United States--to illustrate this concept. We further utilize the Chinese example of 'face' to illustrate stigma as having dimensions that are moral-somatic (where values are linked to physical experiences) and moral-emotional (values are linked to emotional states). After reviewing literature on how existing stigma theory has led to a predominance of research assessing the individual, we conclude by outlining how the concept of moral experience may inform future stigma measurement. We propose that by identifying how stigma is a moral experience, new targets can be created for anti-stigma intervention programs and their evaluation. Further, we recommend the use of transactional methodologies and multiple perspectives and methods to more fully capture the interpersonal core of stigma as framed by theories of moral experience.

Self-concept, social adjustment and academic achievement of Persian students

Stigma-based rejection experiences affect trust in others