近日, 贺建奎团队完成了“首例基因编辑婴儿诞生”的实验(参见, 《参考消息》2019-01-23)。对此, 许多人表示, 贺建奎的行为明显违反了伦理。而且, 贺建奎的道德品质也受到质疑。这一事件的争论焦点在于伦理道德问题。目前, 研究者对道德认知领域进行了大量研究, 但尚未阐明解决道德问题特有的认知机制。随着对行为数据的计算建模方法日臻成熟, 研究者已开始将计算模型运用于道德认知领域。计算模型以数学函数的形式定量地描述选项特征(如代价、收益和等待时间)如何转换为效价, 进而影响决策(Brown, 2014; Charpentier & O’Doherty, 2018; Konovalov, Hu, & Ruff, 2018)。最近的研究已经使用这种方法描述道德效价的计算, 即道德问题的外部特征(如利益、伤害等)如何转化为内部效用, 以及该效用如何指导道德决策、判断和推理(Hackel & Zaki, 2018; Hutcherson, Bushong, & Rangel, 2015; Siegel, Estrada, Crockett, & Baskin-Sommers, 2019; Siegel, Mathys, Rutledge, & Crockett, 2018; Yu, Siegel, & Crockett, 2019)。本文将回顾道德认知的内涵、计算模型在道德认知领域的运用以及其如何促进我们对道德认知过程和相关神经机制的理解。

1 道德认知

贺建奎事件包括:(1)贺建奎做出基因编辑婴儿的决策(decision-making); (2)读者对其特定选择是否符合道德做出判断(judgment); (3)进一步, 读者会对其的道德品质做出推理(inference)。以上对应了道德认知的三个维度——道德决策、判断和推理(本文对道德认知的分类参照了Yu等人(2019)的划分方式1(1Yu等人(2019)将道德认知分为道德决策、道德判断和道德推理三个维度。本文参考了这种划分方式, 并在其基础上对道德认知阐述时进行了补充和扩展。此外, Yu等人提出一个以伤害厌恶为核心的统一计算框架来解释道德认知, 而本文综合考虑了不同模型(漂移扩散模型、效用模型、强化学习模型、分层高斯过筛器和效用模型)在道德认知研究中的应用。), 参见Yu et al., 2018)。它们的定义如下:道德决策是指人们做出影响他人利益的选择; 道德判断是指人们判断行为或心理状态(如情绪、态度等)是否符合道德的过程, 有时包含对某种行为是否应被惩罚或奖励的判断; 道德推理是人们基于对道德相关行为的观察而形成对行为者道德品质(如善或恶)的信念(Yu et al., 2019)。以下我们将从这三个维度展开对道德认知的心理学研究的介绍。

1.1 道德决策

道德决策涉及个体的选择是否损害他人的利益。人有自利倾向(Gray, 1987), 会在诚实/不诚实、公平/不公平和慷慨/自私等决策之间进行权衡。以诚实决策为例, 人们会做出诚实决策(放弃由不诚实带来的额外收益), 还是不诚实决策(获得额外收益)? 以往研究指出, 相比诚实个体, 不诚实个体放弃由不诚实决策获取的利益的时间更长(Greene & Paxton, 2009)。这表明不诚实个体在放弃不诚实利益的过程可能产生更多的认知需求。而且当人们做不诚实选择时, 其心理和生理上均会感到不适(Cohn, Fehr, & Maréchal, 2014; Gächter & Schulz, 2016; Gamer, Rill, Vossel, & Gödert, 2006)。为了减轻这种不适感, 个体会减少不道德行为。此外, 背外侧前额叶皮层损伤的个体对诚实问题的敏感性降低(Zhu et al., 2014), 杏仁核的激活程度与个体不诚实行为的历史呈负相关——个体在当前不诚实决策中杏仁核激活的降低程度预示着下一决策中不诚实的增加程度(Engelmann & Fehr, 2016; Garrett, Lazzaro, Ariely, & Sharot, 2016)。这表明背外侧前额叶皮层和杏仁核对诚实决策的重要作用。综上, 决策往往需要在物质利益和道德价值之间权衡, 但当选择道德决策时, 对物质利益的权重会减小, 人们更加关心如诚实、慷慨等道德价值。

1.2 道德判断

道德判断基于道德决策, 指人们判断决策或决策者应被给予奖励还是施加惩罚。电车困境是研究道德判断的常用范式——想象一辆失控的电车即将撞死铁轨上的5名工人, 决策者可以选择什么都不做, 5名工人会死亡; 或扳动开关将电车转向一个侧道, 那里的1名工人会死亡(Kamm, 2015)。根据人们对两种选择的道德认可程度, Greene (2007)提出道德判断的双过程模型——义务性和功利性道德判断, 即支持决策者什么都不做是一种义务性判断(在义务论道德体系下, “不可主动杀人”是一项道德义务), 而支持决策者牺牲1个人拯救5个人是一种功利性判断(在功利主义道德体系下, 1人死亡比5人死亡价值更高); 前者由情感驱动, 是快速、自动的过程; 后者由认知驱动, 是缓慢、需要动机和认知资源参与的过程。研究表明, 在产生共情的情况下, 个体做出义务性道德判断的频率增加; 而个体与受害者接触较少或倾向于理性思维方式时, 做出功利性道德判断的频率增加(Elqayam, Wilkinson, Thompson, Over, & Evans, 2017; Greene, 2014)。进一步发现, 血清素通过增加个体对伤害他人的厌恶, 降低人们做出功利性判断的可能性(Crockett, Clark, Hauser, &Robbins, 2010)。相反, 腹内侧前额叶皮层损伤的个体做出异常高的功利性判断(Koenigs et al., 2007), 表明腹内侧前额叶皮层是直觉的、情感系统的关键神经基质, 对正常的道德判断至关重要。综上, 伤害厌恶是一种亲社会情绪, 直接影响道德判断和道德行为, 也在治疗反社会和攻击性行为中的应用有一定的启示。

1.3 道德推理

道德推理的核心是由可观察的、已知的现象(如他人的外显行为)推断内隐的、未知的状态(如他人行为背后的动机或他人的道德品质)。近年来, 道德推理研究的焦点是对行为的评价, 即个体指出影响他们进行道德推理的特征。研究表明, 负性行为(如偷盗)比正性行为(如捐赠)更能代表个体的道德品质(Eisenegger, Naef, Snozzi, Heinrichs, & Fehr, 2010; Uhlmann, Pizarro, & Diermeier, 2015)。捐赠可能由其他动机驱动(如维护自己的社会地位), 供人推理的信息比较少; 而偷盗的动机大多是负面的(如利己、反社会等), 从而更容易推断偷盗者的道德品质。这表明个体进行道德推理时受信息量高低的影响。另有研究表明, 人们通常给予伪君子(一边谴责不道德行为, 一边做着不道德行为的人)负性评价(Jordan, Sommers, Bloom, & Rand, 2017; Levine, Barasch, Rand, Berman, & Small, 2018)。然而, 伪君子通过承认不道德行为来避免向他人发出虚假信号, 人们对他们的评价则没那么负性。这表明人们对行为者发出虚假的道德信号比较反感。此外, 有害的行为(如从超市偷了一只死鸡)比无害但不洁的行为(如煮食自己死去的宠物狗)更不道德, 但后者中行为者的道德品质更低下(Uhlmann & Zhu, 2014)。这表明, 以个体品质为中心的道德推理, 通常比行为的后果或是否违背道德准则更重要。综上, 道德推理是深思熟虑的和直觉的过程(Garon, Lavallée, Estay, & Beauchamp, 2018)。

2 计算模型

计算机的发展与应用加快了计算建模研究的速度, 为科学研究提供了更先进、严谨的手段。计算模型以数学函数的形式, 将实验中可观察到的变量(如刺激、结果或过去的经验)与近期的行为联系起来, 并对行为产生的不同算法假设进行量化。研究者们通过将实验数据与模型进行拟合, 探究行为背后的算法, 使用精确的数学模型更好地理解行为数据。

近年来, 计算模型在心理学研究领域被广泛应用, 如感知觉、决策、记忆和学习等方面。Jiang, Summerfield和Egner (2016)将计算模型与行为和神经成像数据结合起来, 揭示了视觉对象不同的特征预期(和注意力)如何在驱动感知决策和神经表征的过程中相互作用, 并表明视觉对象是预测视觉的选择单位。简单地说, 当视觉对象的一个特征在预期之外时, 这种预测误差会传播到其他特征, 使该对象的其他特征也在预期之外, 于是该视觉对象整体在预期之外。此外, 人们也会从经验中获得的价值预期生成决策。Meder等人(2017)提出个体在决策过程中同时表征一系列动态变化的价值评估可以作为一种灵活的选择机制, 将经验获得的价值信息与价值的其他特征结合起来, 从而在变化的环境中做出自适应的决策。为了更好的适应环境, 个体可能依据外部环境或自身状态来灵活地调整对选项所赋予的价值, 从而形成主观偏好。Ai等人(2018)通过建立数学模型, 将决策与记忆的动态提取过程相结合, 证明了主观偏好变化与睡眠状态下相关记忆的巩固有关。更有价值的是, 研究者们利用计算模型探究精神障碍(如创伤后应激障碍)和生理损伤(如基底核损伤)患者的学习机制, 为其恢复正常功能的治疗提供有力证据(Brown et al., 2018; Zhu, Jiang, Scabini, Knight, & Hsu, 2019)。这些研究对心理学以及临床医学领域的未来研究都有着重要的启示意义。

事实上, 道德认知在日常生活和心理学中都占有举足轻重的地位。为阐明道德决策、道德判断和道德推理的认知过程和神经机制, 将计算建模这一强大的手段运用于道德认知领域也是应时而生的。以下将回顾在道德认知及其他领域运用都比较广泛的计算模型——漂移扩散模型、效用模型、强化学习模型和分层高斯过筛器模型。

2.1 漂移扩散模型

漂移扩散模型(Drift Diffusion Models, DDM)最早由Ratcliff (1978)开发, 它把决策描述为一个连续的抽样过程, 即带有噪声的信息从起点累积到对应于某一选项的边界或阈值(即标准), 该选项被选中(Ratcliff & McKoon, 2008)。公式如下:

$dy(t)=v(\Delta u)\cdot dt+\sigma \cdot dW$

公式中$\Delta V={{\text{U}}_{A}}-{{\text{U}}_{B}}$是在时间t时积累的信息量; $\Delta u$是两个选项边界的差异; $v$是信息累积的速度(即漂移率); $\sigma $是维纳过程$dW$的高斯噪声参数。此外, DDM的参数还包括起始点偏移量、边界高度和非决策时间等。漂移率代表偏好强度, 即个体倾向于某一选项的偏好越强烈, 信息向该选项积累的速度就越快。每个选项均有一个边界, 边界表示在做出反应之前必须积累的信息量。而积累过程是有噪声的, 在任意时刻, 信息可能指向两个边界中的一个, 但更多的时候指向正确的边界。而非决策成分包括对刺激的编码(该刺激将驱动决策过程)和从刺激或记忆中提取构成决策基础的刺激的维度。DDM可以将潜在的认知过程体现在模型不同的成分上。例如, 信息积累的速度、边界高度和非决策过程的持续时间(Mormann, Malmaud, Huth, Koch, & Rangel, 2010; Lerche & Voss, 2019; Voss, Rothermund, & Voss, 2004)。而且DDM考虑了所有的行为数据, 即正确反应和错误反应的反应时分布的形状和位置(Ratcliff, Smith, Brown, & Mckoon, 2016; Ratcliff, Thapar, & McKoon, 2004)。

DDM最初适用于基本的知觉和记忆任务等的反应时研究, 例如单项识别和联想识别任务(Ratcliff, 1978; Ratcliff, et al., 2004)、知觉任务(包括亮度、字母、注意定向等)等(Ratcliff, Thapar, & McKoon, 2003; Thapar, Ratcliff, & McKoon, 2003; Smith, Ratcliff, & Wolfgang, 2004)。近10至15年间, DDM在决策过程的心理和神经机制研究中变得越来越重要, 包括感知觉决策、简单的运动决策和基于价值的决策等。Gold和Shadlen (2007)回顾基本的决策形成要素如何在大脑中实现, 从而提出决策是一个权衡先验、证据和价值的过程, 并描述了与关键决策要素(包括深思熟虑和情感认同)相对应的具体数学运算。他们也揭示了感知任务的速度——正确性权衡和简单运动任务的可变的反应时的一种基本机制——将变化的决策变量(随时间累积并存储证据)与固定标准进行比较的决策规则。此外, Krajbich, Armel和Rangel (2010)也用DDM对注视模式和选择之间的关系进行定量预测。结果发现, 在DDM的简单扩展中, 注视点参与价值整合过程, 可以定量地解释注视点和选择之间的各种关系, 以及一些相当大的选择偏差。而且Krajbich等人发现视觉注视过程与价值比较过程存在因果关系。即通过外源性操纵相对注视时间, 个体可能对选择产生偏倚。Eikemo, Biele, Willoch, Thomsen和Leknes (2017)研究阿片类药物对健康人类基于价值的决策的调节时, 用DDM拟合了正确率和反应时的数据, 从而揭示两个决策子过程预期的双向药物效应。总之, DDM可以描述个体如何使用先验、证据和价值来形成决策, 揭示多种形式的决策(如知觉决策、简单的运动决策和基于价值的决策等)背后的一般原则。

2.2 效用模型

DDM通常用于只有两个备选方案的实验任务(即二选一), 且实验每个条件的试次数量要多, 而效用模型(Utility Models)可以更好地解释有更多选项的情况。在经济学领域, 效用函数用于衡量与一组商品和服务有关的偏好。效用常常与幸福感和满意度等有关, 而这些难以直接观测。因此, 经济学家利用效用函数来表征这些抽象的、不可直接测量的变量(Debreu,1954)。后来, 效用函数被用于社会决策领域, 它将可供选择的选项的价值传达给决策者, 促使决策者选择价值(即效用)最大的选项。效用模型的简单公式如下(假设有两个选项):

$\Delta V={{\text{U}}_{A}}-{{\text{U}}_{B}}$

公式中${{\text{U}}_{A}}$是选项A的效用; ${{\text{U}}_{B}}$是选项B的效用; $\Delta V$是个体的主观价值。在每一个试次中, 被试对每个选项有不同的偏好, 当且仅当被试更喜欢选项A而不是B时, A的效用量才大于B。因此, 当$\Delta V>0$时个体才会选择选项A。通常, 之后会用softmax函数估计被试的选择概率。

在社会决策领域中, 效用模型主要用于探讨社会偏好或道德偏好。研究者们将效用模型与功能磁共振成像相结合, 研究社会价值的神经表征, 以评估他们对自我和他人利益的分配(Liu et al., 2019; Qu, Météreau, Butera, Villeval, & Dreher, 2019; Zhong, Chark, Hsu, & Chew, 2016)。这种研究方法在一定程度上解读了代表自我和他人潜在利益的神经机制, 对于理解社会决策至关重要。此外, Lopez-Persem, Rigoux, Bourgeois-Gironde, Daunizeau和Pessiglione (2017) 在不同任务中得到了相同的效用函数, 并且对选择的预测准确性很高。这表明了可比较的效用函数不仅可以解释经济选择, 而且可以解释不同的动机导向行为。值得注意的是, 效用模型假设个体的偏好是固定的。因为如果根据价格或预算变化来改变人们的行为, 将无法确定行为变化在多大程度上是由于价格或预算变化还是偏好的改变所致。

2.3 强化学习模型

上述的漂移扩散模型和效用模型被广泛应用于决策领域, 而强化学习模型(Reinforcement Learning Models)则是解决决策中的不确定性问题以及各种学习问题的强大工具, 包括与游戏相关的问题(如Tesauro, 1995)、自行车骑行问题(如Randløv & Alstrøm, 1998)和机器人控制(如Riedmiller, Gabel, Hafner, & Lange, 2009)等。许多不同的强化学习算法已经开发出来解决这些问题(Szepesvari, 2010; Sutton & Barto, 1998)。学习主体通过反复试验, 形成刺激与结果关联来优化获得未来奖励的可能性, 从而灵活地选择获得奖励的行为, 这一过程被称为强化学习。强化学习的关键是预测误差, 即预期事件和获得事件之间的差异, 然后用于更新对环境中事件的信念(Sutton & Barto, 1998)。此外, 强化学习模型中最典型和广泛使用的是Rescorla-Wagner模型, 该模型通过预测误差信号表征学习, 概念简单, 计算效率高(Rescorla & Wagner, 1972)。Rescorla-Wagner模型假设, 在时间k时, 大脑计算和更新行为变量Qk的值如下:

Qk+1 = Qk + α · δk

公式中α是学习率; δk是预测误差, 在时间k收到的实际奖励与预期奖励之间的差值; Qk是当前的期望; Qk+1是个体对未来奖励的期望。强化学习系统的目标是学习一种行为策略, 使个体选择的动作或行为获得最大累计奖赏值。

强化学习模型解释了基于行为和基于结果的价值表征之间的区别, 将其与自动加工与控制加工联系起来, 并精确地阐明了认知和情感机制对这两种类型的加工的贡献。一方面, 基于模型的强化学习激活杏仁核、海马和眶额皮质等脑区(Andrews-Hanna, Reidler, Sepulcre, Poulin, & Buckner, 2010; Zsuga, Biro, Papp, Tajti, & Gesztelyi, 2016)。具体地, 杏仁核与腹侧纹状体联合编码刺激(即预期结果之外的事件), 而海马与腹侧纹状体联合编码上下文(即结果的偶然性)。此外, 眶额皮层由海马和杏仁核驱动, 将与奖励相关的信息整合到上下文框架中。因此, 眶额皮层将提供关于预期奖励的信息, 从而计算出奖励预期(Wallis, 2007)。另一方面, 无模型强化学习也能够激活腹侧纹状体(Zsuga et al., 2016)。那么, 眶额皮层提供的奖励预期信息反馈给无模型系统, 基于腹侧纹状体的功能连通性, 使腹侧纹状体可以将基于模型的奖励信息与无模型的奖赏预测误差相结合, 计算腹侧纹状体发出的价值信号。所以, 基于模型的强化学习和无模型强化学习并非相互分离, 而是具有功能连通性。

2.4 分层高斯过筛器模型

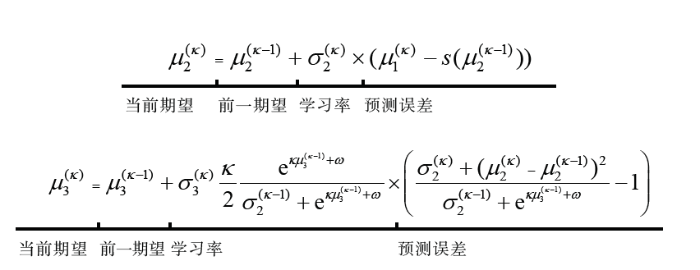

强化学习模型为简单的学习和决策行为及其神经基础的功能提供了强大的解释。但是在现实中, 涉及许多刺激和动作的情况下, 这些算法的学习效率低, 不能及时捕捉人类学习的速度, 而造成这种差异的一个原因是人类利用了现实世界任务中固有的结构来简化学习问题(Gershman & Niv, 2010)。所以, 改进强化学习模型是不可避免的。Mathys, Daunizeau, Friston和Stephan (2011)受到Behrens, Woolrich, Walton和Rushworth (2007)开创性工作的启发, 提出一个分层高斯过筛器(Hierarchical Gaussian Filter, HGF)模型, 用于在多种形式的不确定性(如环境波动和感知不确定性)下的个体学习。该模型包含了一个状态层次结构, 这些状态在时间上演化为高斯随机游动(Gaussian random walks), 每一个游动(除第一级水平外)的幅度大小由层次结构的下一个最高水平决定。水平之间的耦合由参数控制。这些参数编码了环境中关于高阶结构的先验信念, 使模型能够解释学习中的个体差异包括个体间差异以及跨时间的个体差异。HGF可以加工离散状态和连续状态, 并且可以解释环境事件与感知状态之间的确定性和概率关系, 能够推导出控制环境中突发事件的所有隐藏状态的后验期望的封闭式更新方程, 使得HGF计算效率很高, 能够实时学习。这些更新方程的形式类似于Rescorla-Wagner模型, 为强化学习理论提供了一个贝叶斯类比。Rescorla-Wagner模型的结构是:当前期望 = 前一期望 + 学习率 ×预测误差, HGF的更新方程形式如图1。

图1

图1

分层高斯过筛器的更新方程与Rescorla-Wagner模型结构的对比。${{\mu }^{(k-1)}}$是前一后验概率; \[{{\mu }^{(k)}}\]是当前新的后验概率(具体参数参见Mathys et al., 2011)。

Mathys等人(2014)进一步阐述HGF如何为加工感知中的不确定性提供一种通用的方法, 将HGF的层次结构扩展到任意数量, 探讨了如何通过更新方程中编码的变分自由能的最小化来适应各种形式的不确定性。总之, HGF为理解正常和非正常学习提供了一个新的基础, 它将强化学习置于一个通用的贝叶斯方法中, 从而将其与概率论中的最优原则联系起来。它为解决行为者的感知不确定性提供了一个有原则的、灵活的、有效的同时又直观的框架。

HGF是一种学习模型, 它的特点是假定了个体进行社会学习时, 形成关于他人印象的过程发生在多个认知层面上。在这里以两个认知层面:外显和内隐层面为例, 外显可观测的层面是他人的具体行为, 内隐(hidden)层面是观察者内心(或说头脑里)对他人的印象。HGF可以计算给出外显层面的信息(即每次观察到他人的具体行为)如何推动内隐层面的表征的变化, 即给出了一种“生成模型”。Siegel等人(2018)选用HGF来探究个体道德推理的计算基础及其时间动态, 就是因为它能解释内隐印象和外显观察到行为的关系, 以说明外显行为观测如何推动印象形成。综上, 借助实用的方法来开发人类认知的计算模型, 这些模型基于可靠的概率原理, 可以解释日常思维、推理和学习的丰富性和复杂性。

3 计算模型在道德认知领域的运用

计算模型可以估计道德认知过程中内隐的、不可观测到的潜在成分(反映认知过程的参数)。研究者可以解释和预测这些潜在成分的具体认知加工过程, 发展与完善道德认知的心理学理论。计算模型可以连接道德认知和道德神经科学, 通过不同层面的计算模型, 更加全面地解释和预测道德认知的神经机制。例如, 研究者利用计算模型结合神经影像学, 揭示心理学理论中潜在的、不能直接观察到的、与行为有关的神经活动过程和认知加工成分, 如强化学习中的关键变量——奖赏预测误差(Sven, Wolfgang, Peter, & John, 2017)。本部分将回顾上面介绍的漂移扩散模型、效用模型、强化学习模型和分层高斯过筛器模型如何运用于道德认知领域(见表1)。

表1 计算模型在道德认知研究中的应用总结

| 模型 | 道德决策 | 道德判断 | 道德推理 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 漂移扩散模型 | Chen & Krajbich, 2018 Hutcherson et al., 2015 Krajbich et al., 2015 | ||

| 效用模型 | Crockett et al., 2014, 2015, 2017 Gao et al., 2018 Hu et al., 2018 Sáez et al., 2015 Strombach et al., 2015 Yu et al., 2019 Zhu et al., 2014 | Yu et al., 2019 | Yu et al., 2019 |

| 强化学习模型 | Yu et al., 2019 | Hackel, et al., 2015 Hackel & Zaki, 2018 Shenhav & Greene, 2010, 2014 Yu et al., 2019 | Hackel et al., 2015 Joiner et al., 2017 Suzuki et al., 2012 Yu et al., 2019 |

| 分层高斯过筛器模型 | Siegel et al., 2018, 2019 |

注:

3.1 计算模型在道德决策中的运用

人们在面对不同价值的选择时, 并不总是依据利益最大化原则, 选择价值更高的选项(Behrens, Hunt, & Rushworth, 2019; Crockett, Kurth-Nelson, Siegel, Dayan, & Dolan, 2014; Crockett et al., 2015)。有研究指出, 人们考虑到他人的利益, 而做出偏离自己利益最大化选择的程度与其道德行为呈正相关(Hutcherson et al., 2015; Yu et al., 2019)。

Hutcherson等人(2015)让被试决定是否接受给自己和对家的分钱方案, 探究人们的慷慨决策。在DDM中, 每个试次的选择都基于动态变化的随机相对决策值信号, 来估计相较于默认方案, 对分配方案的预期。当随机相对决策值信号超过阈值时, 被试会做出反应(如果是正值, 接受分配方案; 反之, 则拒绝分配方案), 反应时等于信息累积时间与非决策时间之和。结果发现, 对他人的慷慨程度与自己的权重和启动阈值呈负相关, 与漂移率呈正相关(Hutcherson et al., 2015; Konovalov & Krajbich, 2019)。此外, 慷慨误差(错误地选择给予他人更多金钱)的比率明显高于自私误差(错误地选择保留更多金钱)的比率, 这表明当个体获得的奖赏比别人获得的奖赏更有价值时, 他/她的慷慨行为可能反映的是噪声干扰, 而不是真正的亲社会偏好。在神经层面, 个体在加工自己利益的过程中, 腹内侧前额叶皮层和腹侧纹状体激活更强, 而在加工他人利益的过程中, 腹内侧前额叶皮层、右侧颞顶联合区和楔前叶激活更强。这表明加工自己利益和他人利益在大脑中是各自独立表征的。而且腹内侧前额叶皮层将关于自己利益和他人利益组合成一个整体值, 并通过DDM的算法整合分配方案的总金额来做出选择。通过DDM对决策过程的随机相对决策值信号、漂移率、边界高度、起始点偏移量和非决策时间成分参数的拟合而推导和测试出, 与自私决策相比, 在做出慷慨决策前, 与选项信息累积和价值计算相关脑区更活跃。这些研究结果揭示了道德价值表征背后的神经计算机制, 并表明可能通过调节腹内侧前额叶皮层的道德价值表征来促进亲社会性。

Krajbich, Hare, Bartling, Morishima和Fehr (2015)通过DDM发现社会决策(自私或慷慨)的速度和一致性可以通过从非社会决策(如食物选择) 中得到的模型参数来预测, 表明这两个领域的决策可能有着相同的加工模式。此外, 对于社会决策是单一的比较过程还是双重过程(直觉的和深思熟虑的)问题, Chen和Krajbich (2018)提出归因于直觉的行为可以作为DDM过程的起点偏差, 这种起点偏差类似于贝叶斯框架中的先验偏差。在独裁者博弈任务中, 被试对如何在自己和对家之间分配金钱做出二元决策。结果发现, 在时间压力下, 亲社会个体变得更亲社会, 而在时间延迟下, 亲社会个体数量变少。这些发现有助于统一关于社会决策认知加工过程的争论。

Crockett等人(2014)让被试决定是否给自己和他人施加电击以换取利益(获得金钱数量随电击数量增加而增加), 来探究人们的道德决策。Crockett等人在效用模型中使用了选项与默认选项之间的金钱差异和电击差异、损失厌恶参数和伤害厌恶参数, 量化了被试给自己和他人带来的痛苦的相对价值。当伤害厌恶参数等于0时, 决策者有最小的伤害厌恶, 将会接受任何程度的电击来增加自己的收益; 当伤害厌恶参数接近1时, 决策者有最大的伤害厌恶, 将会减少自己的收益来避免电击。之后, 利用softmax函数将逐次试验的主观价值转化为选择概率。结果发现即使个体的决策完全是匿名的(未来不会受到不利的评判或惩罚), 他们也更关心他人的痛苦, 而不是自己的痛苦。而且这种对他人痛苦的关心与做出影响他人的决策时反应较慢有关, 与道德决策过程中的深思熟虑一致。计算模型确定了这种亲社会倾向的精确边界, 对于理解人类道德决策具有重要意义。

之后, Crockett等人借助效用模型研究了道德决策中的生理和神经机制。结果发现, 血清素水平的升高, 增加了伤害厌恶和在决策时考虑的时间, 而多巴胺水平的升高则恰恰相反(Crockett, et al., 2015)。血清素和多巴胺在调节道德行为中的这些独特作用, 对社会功能障碍的潜在治疗具有重要意义。道德偏好较强的个体通过伤害他人获取利益时背侧纹状体激活较低, 而外侧前额叶皮层编码了这种罪恶感(Crockett, Siegel, Kurth-Nelson, Dayan, & Dolan, 2017)。这表明伤害厌恶这种道德偏好可能会影响指导我们做出选择的价值观。值得注意的是, 效用模型中的参数会随着不同的道德决策问题(如诚实、公平和慷慨)而有所变化(Gao et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2018; Sáez, Zhu, Set, Kayser, & Hsu, 2015; Strombach et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2014)。

相较于传统研究方法, 漂移扩散模型和效用模型展示了计算模型的价值, 并为道德决策的本质提供了新的见解。它们都很好地解释和预测了自己利益和他人利益的权重对道德决策的影响。相较于非正式模型, 漂移扩散模型和效用模型中的参数虽然会随着道德决策范式的变化而变化, 但研究者们对其有统一的认识使得这些计算模型的解释力更强, 更有利于它们应用于更多的领域中。

3.2 计算模型在道德判断中的运用

在社会中, 由于某些行为会对其他个体产生影响, 人们进而会判断这些行为对他人是有益或有害的。Hackel和Zaki (2018)采取改编的独裁者博弈实验范式, 即在每轮游戏中, 捐赠者(高财富和低财富)选择与接受者分享20%或50%的捐款, 而接受者获得捐赠者分享的金额点数。接受者随机地与捐赠者(2名高财富和2名低财富)配对, 并反复选择与哪名捐赠者互动。因此, 接受者同时了解每个捐赠者的慷慨程度(分享20%捐款的慷慨程度为0, 分享50%捐款的慷慨程度为1)和奖励价值(20%或50% × 捐赠金额点数)。接下来, 接受者完成一项互惠任务, 与每位捐赠者分享金额点数作为回报。Hackel和Zaki利用强化学习模型对接受者的互动选择进行了拟合, 其中, 奖赏预测误差反映了捐赠者的奖赏值和慷慨程度。例如, 捐赠者先分享捐赠的20%, 后分享50%, 就会使接受者产生一个慷慨预测误差(即捐赠者表现得比接受者预期的更慷慨)。接受者对慷慨的捐赠者回报更多(Nowak & Sigmund, 2005), 这是因为接受者对捐赠者进行了一个积极正面的道德判断, 选择对其进行奖励, 因此强化了自己的捐赠行为。在强化学习之后, 人们不仅喜欢慷慨的社交伙伴, 也喜欢那些提供大量物质奖励的人(Feldmanhall, Otto, & Phelps, 2018; Hackel, Doll, & Amodio, 2015; Hackel & Zaki, 2018)。由此可以发现, 道德判断是可以动态学习的, 并引发了后续研究者在道德判断和亲社会行为的学习过程的深入探讨。

Yu等人(2019)在效用模型和强化学习模型的基础上, 提出一个以伤害厌恶为核心的计算模型, 将道德决策、判断和推理的研究问题统一起来, 为揭示道德认知的机制提供了独特的见解。在道德判断方面, 个体在进行道德判断时, 对行为者的责备程度与其选择伤害他人而产生的额外痛苦呈正相关, 但与其选择伤害他人而产生的额外利益呈负相关。这表明, 尽管个体会因损害他人利益责备行为者, 但所获得的利益证明了部分伤害是合理的(Crockett, et al., 2010; Xie, Yu, Zhou, Sedikides, & Vohs, 2014)。总之, 在道德判断中, 获得利益和伤害他人对行为者受责备程度的影响相反。首先, 人们认为伤害他人多于伤害自己获得利益, 或者仅通过伤害他人获得利益, 都会增加人们对不道德行为者的责备程度。其次, 个体自己的伤害厌恶偏好调节获得利益和伤害他人对责备的影响, 所以那些更不愿使他人痛苦的个体更关心伤害而不是收益, 在判断行为者应该被责备或奖励时, 会做出更极端的责备判断。综上, 当行为者产生的负面结果影响他人时, 基于伤害厌恶, 会让判断者予以更多的惩罚, 希望能够降低行为者伤害他人的行为。

除了伤害厌恶, 道德判断也会涉及对不同规模和可能性的结果进行评估, 例如电车困境中的获救人数和获救可能性。Shenhav和Greene (2010)让被试评估牺牲一条生命来拯救一个更大的群体的道德可接受性, 这个群体的规模和不采取行动而死亡的可能性是不确定的, 并基于简单的强化学习模型对数据进行拟合分析。结果发现, 腹内侧前额叶皮层对生死道德判断中预期值的主观表征进行编码, 而腹侧纹状体对预期道德价值特别敏感。同样, 右侧前脑岛对死亡概率特别敏感。这表明, 对影响他人生死攸关的复杂道德决策进行判断时依赖于适应更基本的、涉及物质奖励的自利决策的神经回路。Shenhav和Greene (2014)进一步利用基于模型的强化学习和无模型的强化学习对数据进行拟合分析, 发现自动加工和控制加工对道德判断的影响之间的关键分离, 且由不同的神经结构辅助。杏仁核激活反映了个体对有害的功利主义行为的厌恶和责备程度。在这种综合的道德判断中, 腹内侧前额叶皮层优先参与相对功利主义和情感评价加工(Shenhav & Greene, 2014)。杏仁核和腹内侧前额叶皮层的功能连接随着任务中情绪输入所起的作用而变化, 在纯功利主义判断中最低, 在纯情绪判断中最高(Shenhav & Greene, 2010, 2014)。这些发现表明杏仁核对所判断的行为提供了情感评估, 而腹内侧前额叶皮层则将这种信号与对预期结果的功利主义评估结合起来, 得出经过深思熟虑的道德判断的结果。总之, 研究者对道德认知的神经基础的探索发现, 在道德判断过程中, 大脑区域始终处于激活状态(Crockett et al., 2017; Shenhav & Greene, 2010)。进一步, 计算模型可以精确地指定在道德判断过程中由大脑区域提供的计算。这促进了道德神经科学的发展, 并加强了观察到的大脑和行为变化之间的联系。

3.3 计算模型在道德推理中的运用

道德推理是一个宽泛的概念, 是个体指出影响他们进行道德评价的行为特征(如行为的结果和行为者的意图等)的过程, 不一定是对善与恶的推理。一切通过社会学习去推断他人特征(如个体知觉和印象形成等)都可以看作道德推理(Feldmanhall, Dunsmoor, et al., 2018; Hackel et al., 2015; Joiner, Piva, Turrin, & Chang, 2017; Suzuki et al., 2012)。在社会互动中, 推断他人的意图(intention)是形成道德印象的一个基本问题。而道德推理的一个基本挑战是人类如何了解他人的特征来预测自己的决策行为。研究表明, 攻击者的道歉不仅会降低受害者的反应性攻击, 还会改变攻击者对冒犯者的内隐态度(Beyens, Yu, Han, Zhang, & Zhou, 2015)。因此, 某行为的道德性很大程度上取决于行为者的意图, 对他人行为背后的意图进行推断是道德判断和道德推理重要的环节。

Siegel等人(2018)采用分层高斯过筛器来探究个体道德推理的计算基础及其时间动态。被试(正常大学生)预测并观察了两名行为者的一系列选择——是否对另一个人施加痛苦的电击以换取金钱, 评估他们对行为者道德品质的印象以及不确定性。个体形成关于行为者道德品质的信念由概率分布表示, 其中均值描述了每个试次后关于行为者的信念, 并且方差描述了该信念的不确定性。信念随着时间的更新表征为高斯随机游动, 其更新大小由表示信念波动的个体差异决定。结果表明, 个体对不道德行为者的道德信念比对道德行为者的更具不确定性, 并伴有更快的学习速度。这种机制可以使个体灵活地更新关于他人的信念。当最初的负面道德印象被证明不准确时, 这种机制可以促进宽恕。

之后, Siegel等人(2019)同样采用分层高斯过筛器研究男性服刑人员接触暴力对伤害学习的影响。结果发现接触暴力的个体形成了整体的主观社会印象, 并将这些印象转化为社会决策, 但会破坏其道德推理能力(认为道德行为者不值得信任, 反而认为不道德行为者更值得信任), 从而导致更多的不道德行为。这是因为人们错误地把不好的特征归于好人会破坏现有的关系, 阻碍建立新的关系(Johnson, Blumstein, Fowler, & Haselton, 2013)。因此, 准确地推断他人道德品质的能力对健康的社会功能至关重要。从道德决策到道德推理是一个社会学习的过程, 探究其认知和神经机制对于矫正服刑人员的认知、训练自闭症和抑郁症等精神障碍群体适应正常的社会功能等有重要意义。

Suzuki等人(2012)利用强化学习模型, 证明了个体模仿他人决策包括两个层次的学习信号。在模仿学习中, 个体同时呈现两种不同的预测误差信号——模仿他人的奖赏预测误差和行为预测误差。个体模仿他人决策时, 腹内侧前额叶皮层来模仿他人的特征以生成预测, 并使用背内侧前额叶皮层和背外侧前额叶皮层来辅助行为变化以改进预测。Hackel等人(2015)也利用强化学习模型揭示了个体在学习任务中通过反馈编码了奖赏和特征信息。除了特定的奖赏加工外, 特征信息(如慷慨或自私等)通过反馈进行编码, 并且在决策过程中, 特征信息可以支配奖励信息。这两种学习方式都与腹侧纹状体的预测误差信号有关。对他人的印象也可以通过基于反馈的工具学习形成(Hackel et al., 2015)。简单举例阐述, 某位同学与大家分享资源, 可能不仅会收到回报, 还被认为有慷慨、值得信任与合作等特质。于是她/他在其他情况下也会受到重视, 比如更愿与其合作。此外, Joiner等人(2017)讨论了自我参照和他人参照的奖赏预测误差, 这些误差与多个大脑区域的激活有关(如纹状体、前扣带皮层、前额叶和颞顶联合区等), 有效地使用强化学习模型来调节社会学习。计算模型的应用促进探索社会学习背后的神经机制, 并增强了对道德推理的解释力。

4 不足与展望

道德行为和不道德行为在生活中普遍存在, 但对其认知过程和神经机制的研究仍处于起步阶段。本文回顾了道德认知的三个维度(道德决策、判断和推理)以及几个在道德认知领域广泛运用的计算模型(漂移扩散模型、效用模型、强化学习模型和分层高斯过筛器模型), 并梳理这些计算模型如何阐明道德心理的认知过程和神经机制。值得注意的是, 漂移扩散模型、效用模型、强化学习模型和分层高斯过筛器模型与道德决策、判断和推理并不是一一对应的关系。计算模型更多地是与数据类型和实验设计相关, 而心理过程上则可能没有这样的对应。例如, 漂移扩散模型与强化学习模型结合使用, 应用于道德认知的研究中, 这可以作为研究者们将来研究的方向。相较于传统研究方法和非正式模型, 计算模型准确地描述道德决策、判断和推理的认知过程, 以及其潜在的神经关联。此外, 研究者使用计算模型来研究道德领域的问题有助于解决关于道德认知中伤害的中心地位的争论(Schein & Gray, 2015, 2018)。

由于本文以道德认知领域为中心, 所以未详细讨论使用上述计算模型进行研究的其他领域, 例如, 资源分配(Konovalov et al., 2018)、精神障碍(Chen, Takahashi, Nakagawa, Inoue, & Kusumi, 2015; Rothkirch, Tonn, Köhler, & Sterzer, 2017)等。对这些领域的研究也明显受益于计算模型的使用。注意, 这里所讨论的特定模型可能不会完全地适用于所有类型的社会行为, 因此可能需要开发不同的计算方法。本文着重梳理了几个在道德认知领域广泛应用的计算模型以及它们如何应用于道德认知领域。所以, 研究中也有其他能够解释道德认知问题的模型我们没有讨论, 如多项加工树模型(预先规定了不同的过程如何作为实验输入和行为输出, 主要用于对道德两难问题的研究; 刘媛媛, 丁一, 彭凯平, 胡传鹏, 2019; Cameron, Payne, Sinnott-Armstrong, Scheffer, & Inzlicht, 2017; Gawronski, Conway, Armstrong, Friesdorf, & Hütter, 2018)和部分观测者马尔科夫决策过程模型(是贝叶斯模型的一种, 主要用于探讨社会情境下的信念学习; Khalvati et al., 2019)等。目前, 没有一个单一的计算模型可以为道德认知提供一个明确和统一的机制。正如简单地为机器人提供一组“如果-那么”的规则来适应特定的情况非常困难, 因为机器人可能发现自己处于无限多的情况中。从单一研究中得出的参数也不能作为适用于道德认知的各个组成部分的数字权重的最终结论。

前面的部分已经介绍了使用计算模型来研究道德认知的一些优点, 这里强调与这种方法相关的潜在问题。首先, 使用不同的模型来获得价值、信念或选择过程会存在一定的风险——模型的选择(而不是行为本身)决定了研究者研究的重点。例如, 用于解释信念学习或偏好的模型(和任务)不同, 至少驱动这些行为的过程中的一些差异反映了不同计算模型的使用。道德认知领域的进一步发展将会需要更统一的方法来对不同类型的认知进行建模。这个问题可以通过信任的相关研究来说明, 信任主要表现为一个学习问题——由于信任他人使自己容易受到他人的背叛, 人们必须解决潜在利益与至少三种其他担忧之间的冲突:损失厌恶、不公平厌恶和背叛厌恶(Bohnet & Zeckhauser, 2004)。很少有研究考察在信任-不信任决策中这些厌恶背后的神经计算机制, 这些机制可以用混合模型对这些不同的关注点分配权重来研究(Nave, Camerer, & McCullough, 2015)。

其次, 虽然计算模型可以促进研究者对道德认知的理解和预测, 但它们提供对潜在认知、学习和过程的看法有限。一些模型适合行为和大脑活动, 这在很大程度上是因为它们能够灵活地适应许多不同模式的数据。因此, 实证研究应该努力提供证据, 证明模型的潜在参数实际上反映了可以通过实验干预选择性的改变(Hill et al., 2017)。最终, 好的模型是那些能够构建关于驱动道德认知研究的模型, 正如经典理论一样, 但是现在有了一个更加定量和机械论的焦点。本质上, 所有的模型都是错误的, 但有些是有用的, 可以为道德认知理论做出贡献。

最后, 由于模型构建过程本身是比较多样和灵活的, 因此如何能够保证计算模型不被滥用和误用也是非常重要的。Lee等人(2019)提出了一种技术和实践方法, 包括预注册模型、提供模型并在探索性模型开发后注册、对模型进行详细的评估和注册建模报告, 使心理建模更加透明、可信、有效和稳定。构建适合计算建模的范例可能需要在现实世界的丰富性与方法论的严谨性之间进行权衡。识别一个对行为或大脑活动提供良好匹配的计算模型并不能保证所识别的模型是最好或最准确的模型(Mars, Shea, Kolling, & Rushworth, 2012)。此外, 认知计算建模的一个重要且经常被忽视的方面是根据观测数据模拟候选模型(Palminteri, Wyart, & Koechlin, 2017)。尽管存在这些限制, 但是计算模型有益于定量测量不依赖于自我报告的道德认知的个体差异, 而自我报告在测量具有强烈社会赞许性成分的特征方面可能不太可靠。此外, 模型参数可作为生物学和现象学的中间水平或认知表型, 描述特定临床或亚临床和精神状态如何影响道德认知和行为, 如抑郁症(Chen et al., 2015; Rothkirch et al., 2017)、精神分裂症(Valton, Romaniuk, Steele, Lawrie, & Seriès, 2017)和人格障碍(Tyrer, Reed, & Crawford, 2015)等。因此, 使用计算模型不仅极大地促进我们对人类道德的理解, 而且也逐渐地运用于计算精神病学和其他疾病, 希望减少人类在疾病方面的痛苦。

5 结论

描述道德决策、判断和推理的计算模型代表了量化道德认知以及客观指导理解道德行为的认知过程的第一步。这些计算模型以数学方程的形式描述了道德选择的输入如何转化为输出。计算模型的优势在于它们提供了一种通用的数学语言, 可以用来比较不同道德认知研究的效果大小。随着越来越多的研究应用这些计算模型, 研究者们将其汇总, 可以上升到理论层面(如描述如何结合道德决策、判断和推理成分为道德认知领域完善某种理论或提出新的理论), 也可以为临床领域提供经验和帮助(如计算精神病学)。目前, 计算模型在道德认知领域的研究刚刚起步, 相对少数的模型可以捕捉到道德认知的大部分方面, 或者, 人类道德的丰富性和复杂性可能无法归结为一组可管理的数学方程, 这是有待研究者们解决的问题。

参考文献

Promoting subjective preferences in simple economic choices during nap

DOI:10.7554/eLife.40583

URL

PMID:30520732

[本文引用: 1]

Sleep is known to benefit consolidation of memories, especially those of motivational relevance. Yet, it remains largely unknown the extent to which sleep influences reward-associated behavior, in particular, whether and how sleep modulates reward evaluation that critically underlies value-based decisions. Here, we show that neural processing during sleep can selectively bias preferences in simple economic choices when the sleeper is stimulated by covert, reward-associated cues. Specifically, presenting the spoken name of a familiar, valued snack item during midday nap significantly improves the preference for that item relative to items not externally cued. The cueing-specific preference enhancement is sleep-dependent and can be predicted by cue-induced neurophysiological signals at the subject and item level. Computational modeling further suggests that sleep cueing accelerates evidence accumulation for cued options during the post-sleep choice process in a manner consistent with the preference shift. These findings suggest that neurocognitive processing during sleep contributes to the fine-tuning of subjective preferences in a flexible, selective manner.

Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain’s default network

The computation of social behavior

DOI:10.1126/science.1169694

URL

PMID:19478175

[本文引用: 1]

Neuroscientists are beginning to advance explanations of social behavior in terms of underlying brain mechanisms. Two distinct networks of brain regions have come to the fore. The first involves brain regions that are concerned with learning about reward and reinforcement. These same reward-related brain areas also mediate preferences that are social in nature even when no direct reward is expected. The second network focuses on regions active when a person must make estimates of another person's intentions. However, it has been difficult to determine the precise roles of individual brain regions within these networks or how activities in the two networks relate to one another. Some recent studies of reward-guided behavior have described brain activity in terms of formal mathematical models; these models can be extended to describe mechanisms that underlie complex social exchange. Such a mathematical formalism defines explicit mechanistic hypotheses about internal computations underlying regional brain activity, provides a framework in which to relate different types of activity and understand their contributions to behavior, and prescribes strategies for performing experiments under strong control.

Learning the value of information in an uncertain world

DOI:10.1038/nn1954

URL

PMID:17676057

[本文引用: 1]

Our decisions are guided by outcomes that are associated with decisions made in the past. However, the amount of influence each past outcome has on our next decision remains unclear. To ensure optimal decision-making, the weight given to decision outcomes should reflect their salience in predicting future outcomes, and this salience should be modulated by the volatility of the reward environment. We show that human subjects assess volatility in an optimal manner and adjust decision-making accordingly. This optimal estimate of volatility is reflected in the fMRI signal in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) when each trial outcome is observed. When a new piece of information is witnessed, activity levels reflect its salience for predicting future outcomes. Furthermore, variations in this ACC signal across the population predict variations in subject learning rates. Our results provide a formal account of how we weigh our different experiences in guiding our future actions.

The strength of a remorseful heart: Psychological and neural basis of how apology emolliates reactive aggression and promotes forgiveness

Trust, risk and betrayal

The tale of the neuroscientists and the computer: Why mechanistic theory matters

Associability-modulated loss learning is increased in posttraumatic stress disorder

DOI:10.7554/eLife.30150

URL

PMID:29313489

[本文引用: 1]

Disproportionate reactions to unexpected stimuli in the environment are a cardinal symptom of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Here, we test whether these heightened responses are associated with disruptions in distinct components of reinforcement learning. Specifically, using functional neuroimaging, a loss-learning task, and a computational model-based approach, we assessed the mechanistic hypothesis that overreactions to stimuli in PTSD arise from anomalous gating of attention during learning (i.e., associability). Behavioral choices of combat-deployed veterans with and without PTSD were fit to a reinforcement learning model, generating trial-by-trial prediction errors (signaling unexpected outcomes) and associability values (signaling attention allocation to the unexpected outcomes). Neural substrates of associability value and behavioral parameter estimates of associability updating, but not prediction error, increased with PTSD during loss learning. Moreover, the interaction of PTSD severity with neural markers of associability value predicted behavioral choices. These results indicate that increased attention-based learning may underlie aspects of PTSD and suggest potential neuromechanistic treatment targets.

Implicit moral evaluations: A multinomial modeling approach

The application of computational models to social neuroscience: Promises and pitfalls

Reinforcement learning in depression: A review of computational research

Biased sequential sampling underlies the effects of time pressure and delay in social decision making

Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry

Serotonin selectively influences moral judgment and behavior through effects on harm aversion

Harm to others outweighs harm to self in moral decision making

Moral transgressions corrupt neural representations of value

Dissociable effects of serotonin and dopamine on the valuation of harm in moral decision making

Representation of a preference ordering by a numerical function

Opioid modulation of value-based decision- making in healthy humans

Prejudice and truth about the effect of testosterone on human bargaining behaviour

Utilitarian moral judgment exclusively coheres with inference from is to ought

The slippery slope of dishonesty

DOI:10.1038/nn.4441 URL PMID:27898084 [本文引用: 1]

Stimulus generalization as a mechanism for learning to trust

Learning moral values: Another's desire to punish enhances one's own punitive behavior

Intrinsic honesty and the prevalence of rule violations across societies

Psychophysiological and vocal measures in the detection of guilty knowledge

Distinguishing neural correlates of context-dependent advantageous-and disadvantageous- inequity aversion

Visual encoding of social cues predicts sociomoral reasoning

The brain adapts to dishonesty

Effects of Incidental emotions on moral dilemma judgments: An analysis using the CNI model

Learning latent structure: Carving nature at its joints

The neural basis of decision making

The economic approach to human behavior: Its prospects and limitations. In Radnitzky, G., Bernholz, P.(Eds.)

Why are vmPFC patients more utilitarian? A dual-process theory of moral judgment explains

Patterns of neural activity associated with honest and dishonest moral decisions

Instrumental learning of traits versus rewards: Dissociable neural correlates and effects on choice

Propagation of economic inequality through reciprocity and reputation

A causal account of the brain network computations underlying strategic social behavior

Spreading inequality: Neural computations underlying paying-it-forward reciprocity

A neurocomputational model of altruistic choice and its implications

Visual prediction error spreads across object features in human visual cortex

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1546-16.2016

URL

PMID:27810936

[本文引用: 1]

Visual cognition is thought to rely heavily on contextual expectations. Accordingly, previous studies have revealed distinct neural signatures for expected versus unexpected stimuli in visual cortex. However, it is presently unknown how the brain combines multiple concurrent stimulus expectations such as those we have for different features of a familiar object. To understand how an unexpected object feature affects the simultaneous processing of other expected feature(s), we combined human fMRI with a task that independently manipulated expectations for color and motion features of moving-dot stimuli. Behavioral data and neural signals from visual cortex were then interrogated to adjudicate between three possible ways in which prediction error (surprise) in the processing of one feature might affect the concurrent processing of another, expected feature: (1) feature processing may be independent; (2) surprise might

Social learning through prediction error in the brain

The evolution of error: Error management, cognitive constraints, and adaptive decision-making biases

Why do we hate hypocrites? Evidence for a theory of false signaling

DOI:10.1177/0956797616685771

URL

PMID:28107103

[本文引用: 1]

Why do people judge hypocrites, who condemn immoral behaviors that they in fact engage in, so negatively? We propose that hypocrites are disliked because their condemnation sends a false signal about their personal conduct, deceptively suggesting that they behave morally. We show that verbal condemnation signals moral goodness (Study 1) and does so even more convincingly than directly stating that one behaves morally (Study 2). We then demonstrate that people judge hypocrites negatively-even more negatively than people who directly make false statements about their morality (Study 3). Finally, we show that

Modeling other minds: Bayesian inference explains human choices in group decision-making

Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgements

Neurocomputational approaches to social behavior

DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.009

URL

PMID:29738891

[本文引用: 2]

Social decision-making is increasingly studied with neurocomputational modeling. Here we discuss how this approach allows researchers to better understand and predict behavior in social settings. Using examples from the study of resource distributions and social learning, we illustrate how this methodology provides a flexible way to quantify social values and beliefs, identify specific motives and cognitive processes underlying social choice and learning, and arbitrate between competing theories of social behavior. We also critically discuss open questions and potential problems associated with this methodology.

Revealed indifference: Using response times to infer preferences

Visual fixations and the computation and comparison of value in simple choice

A common mechanism underlying food choice and social decisions

DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004371

URL

PMID:26460812

[本文引用: 1]

People make numerous decisions every day including perceptual decisions such as walking through a crowd, decisions over primary rewards such as what to eat, and social decisions that require balancing own and others' benefits. The unifying principles behind choices in various domains are, however, still not well understood. Mathematical models that describe choice behavior in specific contexts have provided important insights into the computations that may underlie decision making in the brain. However, a critical and largely unanswered question is whether these models generalize from one choice context to another. Here we show that a model adapted from the perceptual decision-making domain and estimated on choices over food rewards accurately predicts choices and reaction times in four independent sets of subjects making social decisions. The robustness of the model across domains provides behavioral evidence for a common decision-making process in perceptual, primary reward, and social decision making.

Robust modeling in cognitive science

Experimental validation of the diffusion model based on a slow response time paradigm

DOI:10.1007/s00426-017-0945-8

URL

PMID:29224184

[本文引用: 1]

The diffusion model (Ratcliff, Psychol Rev 85(2):59-108, 1978) is a stochastic model that is applied to response time (RT) data from binary decision tasks. The model is often used to disentangle different cognitive processes. The validity of the diffusion model parameters has, however, rarely been examined. Only few experimental paradigms have been analyzed with those being restricted to fast response time paradigms. This is attributable to a recommendation stated repeatedly in the diffusion model literature to restrict applications to fast RT paradigms (more specifically, to tasks with mean RTs below 1.5 s per trial). We conducted experimental validation studies in which we challenged the necessity of this restriction. We used a binary task that features RTs of several seconds per trial and experimentally examined the convergent and discriminant validity of the four main diffusion model parameters. More precisely, in three experiments, we selectively manipulated these parameters, using a difficulty manipulation (drift rate), speed-accuracy instructions (threshold separation), a more complex motoric task (non-decision time), and an asymmetric payoff matrix (starting point). The results were similar to the findings from experimental validation studies based on fast RT paradigms. Thus, our experiments support the validity of the parameters of the diffusion model and speak in favor of an extension of the model to paradigms based on slower RTs.

Signaling emotion and reason in cooperation

Oxytocin modulates social value representations in the amygdala

DOI:10.1038/s41593-019-0351-1

URL

PMID:30911182

[本文引用: 1]

Humans exhibit considerable variation in how they value their own interest relative to the interests of others. Deciphering the neural codes representing potential rewards for self and others is crucial for understanding social decision-making. Here we integrate computational modeling with functional magnetic resonance imaging to investigate the neural representation of social value and the modulation by oxytocin, a nine-amino acid neuropeptide, in participants evaluating monetary allocations to self and other (self-other allocations). We found that an individual's preferred self-other allocation serves as a reference point for computing the value of potential self-other allocations. In more prosocial participants, amygdala activity encoded a social-value-distance signal; that is, the value dissimilarity between potential and preferred allocations. Intranasal oxytocin administration amplified this amygdala representation and increased prosocial behavior in more individualistic participants but not in more prosocial ones. Our results reveal a neurocomputational mechanism underlying social-value representations and suggest that oxytocin may promote prosociality by modulating social-value representations in the amygdala.

Choose, rate or squeeze: comparison of economic value functions elicited by different behavioral tasks

DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005848

URL

PMID:29161252

[本文引用: 1]

A standard view in neuroeconomics is that to make a choice, an agent first assigns subjective values to available options, and then compares them to select the best. In choice tasks, these cardinal values are typically inferred from the preference expressed by subjects between options presented in pairs. Alternatively, cardinal values can be directly elicited by asking subjects to place a cursor on an analog scale (rating task) or to exert a force on a power grip (effort task). These tasks can vary in many respects: they can notably be more or less costly and consequential. Here, we compared the value functions elicited by choice, rating and effort tasks on options composed of two monetary amounts: one for the subject (gain) and one for a charity (donation). Bayesian model selection showed that despite important differences between the three tasks, they all elicited a same value function, with similar weighting of gain and donation, but variable concavity. Moreover, value functions elicited by the different tasks could predict choices with equivalent accuracy. Our finding therefore suggests that comparable value functions can account for various motivated behaviors, beyond economic choice. Nevertheless, we report slight differences in the computational efficiency of parameter estimation that may guide the design of future studies.

Model-based analyses: Promises, pitfalls, and example applications to the study of cognitive control

A bayesian foundation for individual learning under uncertainty

Uncertainty in perception and the hierarchical gaussian filter

Simultaneous representation of a spectrum of dynamically changing value estimates during decision making

The drift diffusion model can account for the accuracy and reaction time of value-based choices under high and low time pressure

Does oxytocin increase trust in humans? A critical review of research

DOI:10.1177/1745691615600138

URL

PMID:26581735

[本文引用: 1]

Behavioral neuroscientists have shown that the neuropeptide oxytocin (OT) plays a key role in social attachment and affiliation in nonhuman mammals. Inspired by this initial research, many social scientists proceeded to examine the associations of OT with trust in humans over the past decade. To conduct this work, they have (a) examined the effects of exogenous OT increase caused by intranasal administration on trusting behavior, (b) correlated individual difference measures of OT plasma levels with measures of trust, and (c) searched for genetic polymorphisms of the OT receptor gene that might be associated with trust. We discuss the different methods used by OT behavioral researchers and review evidence that links OT to trust in humans. Unfortunately, the simplest promising finding associating intranasal OT with higher trust has not replicated well. Moreover, the plasma OT evidence is flawed by how OT is measured in peripheral bodily fluids. Finally, in recent large-sample studies, researchers failed to find consistent associations of specific OT-related genetic polymorphisms and trust. We conclude that the cumulative evidence does not provide robust convergent evidence that human trust is reliably associated with OT (or caused by it). We end with constructive ideas for improving the robustness and rigor of OT research.

Evolution of indirect reciprocity

DOI:10.1038/nature04131

URL

PMID:16251955

[本文引用: 1]

Natural selection is conventionally assumed to favour the strong and selfish who maximize their own resources at the expense of others. But many biological systems, and especially human societies, are organized around altruistic, cooperative interactions. How can natural selection promote unselfish behaviour? Various mechanisms have been proposed, and a rich analysis of indirect reciprocity has recently emerged: I help you and somebody else helps me. The evolution of cooperation by indirect reciprocity leads to reputation building, morality judgement and complex social interactions with ever-increasing cognitive demands.

The importance of falsification in computational cognitive modeling

DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2017.03.011

URL

PMID:28476348

[本文引用: 1]

In the past decade the field of cognitive sciences has seen an exponential growth in the number of computational modeling studies. Previous work has indicated why and how candidate models of cognition should be compared by trading off their ability to predict the observed data as a function of their complexity. However, the importance of falsifying candidate models in light of the observed data has been largely underestimated, leading to important drawbacks and unjustified conclusions. We argue here that the simulation of candidate models is necessary to falsify models and therefore support the specific claims about cognitive function made by the vast majority of model-based studies. We propose practical guidelines for future research that combine model comparison and falsification.

Neurocomputational mechanisms at play when weighing concerns for extrinsic rewards, moral values, and social image

DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000283

URL

PMID:31170138

[本文引用: 1]

Humans not only value extrinsic monetary rewards but also their own morality and their image in the eyes of others. Yet violating moral norms is frequent, especially when people know that they are not under scrutiny. When moral values and monetary payoffs are at odds, how does the brain weigh the benefits and costs of moral and monetary payoffs? Here, using a neurocomputational model of decision value (DV) and functional (f)MRI, we investigated whether different brain systems are engaged when deciding whether to earn money by contributing to a

Learning to drive a bicycle using reinforcement learning and shaping

The diffusion decision model: Theory and data for two-choice decision tasks

DOI:10.1162/neco.2008.12-06-420

URL

PMID:18085991

[本文引用: 1]

The diffusion decision model allows detailed explanations of behavior in two-choice discrimination tasks. In this article, the model is reviewed to show how it translates behavioral data-accuracy, mean response times, and response time distributions-into components of cognitive processing. Three experiments are used to illustrate experimental manipulations of three components: stimulus difficulty affects the quality of information on which a decision is based; instructions emphasizing either speed or accuracy affect the criterial amounts of information that a subject requires before initiating a response; and the relative proportions of the two stimuli affect biases in drift rate and starting point. The experiments also illustrate the strong constraints that ensure the model is empirically testable and potentially falsifiable. The broad range of applications of the model is also reviewed, including research in the domains of aging and neurophysiology.

Diffusion decision model: Current issues and history

DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2016.01.007

URL

PMID:26952739

[本文引用: 1]

There is growing interest in diffusion models to represent the cognitive and neural processes of speeded decision making. Sequential-sampling models like the diffusion model have a long history in psychology. They view decision making as a process of noisy accumulation of evidence from a stimulus. The standard model assumes that evidence accumulates at a constant rate during the second or two it takes to make a decision. This process can be linked to the behaviors of populations of neurons and to theories of optimality. Diffusion models have been used successfully in a range of cognitive tasks and as psychometric tools in clinical research to examine individual differences. In this review, we relate the models to both earlier and more recent research in psychology.

A diffusion model analysis of the effects of aging on brightness discrimination

DOI:10.3758/bf03194580

URL

PMID:12812276

[本文引用: 1]

The effects of aging on decision time were examined in a brightness discrimination experiment with young and older subjects (ages, 60-75 years). Results showed that older subjects were slightly slower than young subjects but just as accurate. Ratcliff's (1978) diffusion model was fit to the data, and it provided a good account of response times, their distributions, and response accuracy. There was a 50-msec slowing of the nondecision components of response time for older subjects relative to young subjects, but response criteria settings and rates of accumulation of evidence from stimuli were roughly equal for the two groups. These results are contrasted with those obtained from letter discrimination and signal-detection-like tasks.

A diffusion model analysis of the effects of aging on recognition memory

A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and nonreinforcement. In Black, A. H., Prokasy, W. F.(Eds.)

Reinforcement learning for robot soccer

Neural mechanisms of reinforcement learning in unmedicated patients with major depressive disorder

Dopamine modulates egalitarian behavior in humans

DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.071

URL

PMID:25802148

[本文引用: 1]

Egalitarian motives form a powerful force in promoting prosocial behavior and enabling large-scale cooperation in the human species [1]. At the neural level, there is substantial, albeit correlational, evidence suggesting a link between dopamine and such behavior [2, 3]. However, important questions remain about the specific role of dopamine in setting or modulating behavioral sensitivity to prosocial concerns. Here, using a combination of pharmacological tools and economic games, we provide critical evidence for a causal involvement of dopamine in human egalitarian tendencies. Specifically, using the brain penetrant catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) inhibitor tolcapone [4, 5], we investigated the causal relationship between dopaminergic mechanisms and two prosocial concerns at the core of a number of widely used economic games: (1) the extent to which individuals directly value the material payoffs of others, i.e., generosity, and (2) the extent to which they are averse to differences between their own payoffs and those of others, i.e., inequity. We found that dopaminergic augmentation via COMT inhibition increased egalitarian tendencies in participants who played an extended version of the dictator game [6]. Strikingly, computational modeling of choice behavior [7] revealed that tolcapone exerted selective effects on inequity aversion, and not on other computational components such as the extent to which individuals directly value the material payoffs of others. Together, these data shed light on the causal relationship between neurochemical systems and human prosocial behavior and have potential implications for our understanding of the complex array of social impairments accompanying neuropsychiatric disorders involving dopaminergic dysregulation.

The unifying moral dyad: Liberals and conservatives share the same harm-based moral template

DOI:10.1177/0146167215591501

URL

PMID:26091912

[本文引用: 1]

Do moral disagreements regarding specific issues (e.g., patriotism, chastity) reflect deep cognitive differences (i.e., distinct cognitive mechanisms) between liberals and conservatives? Dyadic morality suggests that the answer is

The theory of dyadic morality: Reinventing moral judgment by redefining harm

DOI:10.1177/1088868317698288

URL

PMID:28504021

[本文引用: 1]

The nature of harm-and therefore moral judgment-may be misunderstood. Rather than an objective matter of reason, we argue that harm should be redefined as an intuitively perceived continuum. This redefinition provides a new understanding of moral content and mechanism-the constructionist Theory of Dyadic Morality (TDM). TDM suggests that acts are condemned proportional to three elements: norm violations, negative affect, and-importantly-perceived harm. This harm is dyadic, involving an intentional agent causing damage to a vulnerable patient (A-->P). TDM predicts causal links both from harm to immorality (dyadic comparison) and from immorality to harm (dyadic completion). Together, these two processes make the

Moral judgments recruit domain-general valuation mechanisms to integrate representations of probability and magnitude

DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.07.020

URL

PMID:20797542

[本文引用: 3]

Many important moral decisions, particularly at the policy level, require the evaluation of choices involving outcomes of variable magnitude and probability. Many economic decisions involve the same problem. It is not known whether and to what extent these structurally isomorphic decisions rely on common neural mechanisms. Subjects undergoing fMRI evaluated the moral acceptability of sacrificing a single life to save a larger group of variable size and probability of dying without action. Paralleling research on economic decision making, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum were specifically sensitive to the

Integrative moral judgment: Dissociating the roles of the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3390-13.2014

URL

PMID:24672018

[本文引用: 3]

A decade's research highlights a critical dissociation between automatic and controlled influences on moral judgment, which is subserved by distinct neural structures. Specifically, negative automatic emotional responses to prototypically harmful actions (e.g., pushing someone off of a footbridge) compete with controlled responses favoring the best consequences (e.g., saving five lives instead of one). It is unknown how such competitions are resolved to yield

Exposure to violence affects the development of moral impressions and trust behavior in incarcerated males

DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-09962-9

URL

PMID:31028269

[本文引用: 2]

Individuals exposed to community violence are more likely to engage in antisocial behavior, resulting in a dramatic increase in contact with justice and social service systems. Theoretical accounts suggest that disruptions in learning underlie the link between exposure to violence and maladaptive behaviors. However, empirical evidence specifying these processes is sparse. Here, in a sample of incarcerated males, we investigated how exposure to violence affects the ability to learn about the harmfulness of others and use this information to adaptively modulate trust behavior. Exposure to violence does not impact the ability to accurately develop beliefs about agents' harm preferences and predict their choices. However, exposure to violence disrupts the ability to form moral impressions that dissociate between agents with distinguishable harm preferences, and subsequently, the ability to adjust trust behavior towards different agents. These findings reveal a process that may explain the association between exposure to violence and maladaptive behavior.

Beliefs about bad people are volatile

DOI:10.1038/s41562-018-0425-1

URL

PMID:31406285

[本文引用: 3]

People form moral impressions rapidly, effortlessly and from a remarkably young age(1-5). Putatively 'bad' agents command more attention and are identified more quickly and accurately than benign or friendly agents(5-12). Such vigilance is adaptive, but can also be costly in environments where people sometimes make mistakes, because incorrectly attributing bad character to good people damages existing relationships and discourages forming new relationships(13-16). The ability to accurately infer the moral character of others is critical for healthy social functioning, but the computational processes that support this ability are not well understood. Here, we show that moral inference is explained by an asymmetric Bayesian updating mechanism in which beliefs about the morality of bad agents are more uncertain (and therefore more volatile) than beliefs about the morality of good agents. This asymmetry seems to be a property of learning about immoral agents in general, as we also find greater uncertainty for beliefs about the non-moral traits of bad agents. Our model and data reveal a cognitive mechanism that permits flexible updating of beliefs about potentially threatening others, a mechanism that could facilitate forgiveness when initial bad impressions turn out to be inaccurate. Our findings suggest that negative moral impressions destabilize beliefs about others, promoting cognitive flexibility in the service of cooperative but cautious behaviour.

Attention orienting and the time course of perceptual decisions: Response time distributions with masked and unmasked displays

DOI:10.1016/j.visres.2004.01.002

URL

PMID:15066392

[本文引用: 1]

Mask-dependent cuing effects, like those previously found in yes-no detection, were found in a task in which observers judged the orientations of orthogonally-oriented Gabor patches presented at cued or uncued locations. Attentional cues enhanced sensitivity for masked, but not unmasked, stimuli. Responses were faster to cued than to uncued stimuli, irrespective of masking. The distributions of response times and accuracy were well described by a diffusion process model of decision making. Mask-dependent cuing was explained by an orienting model in which: (a) decisions are based on stable stimulus representations in visual short term memory that determine the rate of evidence accumulation in the diffusion process; (b) inattention delays the entry of stimuli into short term memory, and (c) masks limit the visual persistence of stimuli.

Social discounting involves modulation of neural value signals by temporoparietal junction

Learning to simulate others' decisions

DOI:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.030

URL

PMID:22726841

[本文引用: 2]

A fundamental challenge in social cognition is how humans learn another person's values to predict their decision-making behavior. This form of learning is often assumed to require simulation of the other by direct recruitment of one's own valuation process to model the other's process. However, the cognitive and neural mechanism of simulation learning is not known. Using behavior, modeling, and fMRI, we show that simulation involves two learning signals in a hierarchical arrangement. A simulated-other's reward prediction error processed in ventromedial prefrontal cortex mediated simulation by direct recruitment, being identical for valuation of the self and simulated-other. However, direct recruitment was insufficient for learning, and also required observation of the other's choices to generate a simulated-other's action prediction error encoded in dorsomedial/dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. These findings show that simulation uses a core prefrontal circuit for modeling the other's valuation to generate prediction and an adjunct circuit for tracking behavioral variation to refine prediction.

Neural computations underlying inverse reinforcement learning in the human brain

DOI:10.7554/eLife.29718

URL

PMID:29083301

[本文引用: 1]

In inverse reinforcement learning an observer infers the reward distribution available for actions in the environment solely through observing the actions implemented by another agent. To address whether this computational process is implemented in the human brain, participants underwent fMRI while learning about slot machines yielding hidden preferred and non-preferred food outcomes with varying probabilities, through observing the repeated slot choices of agents with similar and dissimilar food preferences. Using formal model comparison, we found that participants implemented inverse RL as opposed to a simple imitation strategy, in which the actions of the other agent are copied instead of inferring the underlying reward structure of the decision problem. Our computational fMRI analysis revealed that anterior dorsomedial prefrontal cortex encoded inferences about action-values within the value space of the agent as opposed to that of the observer, demonstrating that inverse RL is an abstract cognitive process divorceable from the values and concerns of the observer him/herself.

Algorithms for reinforcement learning. In

Temporal difference learning and TD-Gammon

A diffusion model analysis of the effects of aging on letter discrimination

DOI:10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.415

URL

PMID:14518805

[本文引用: 1]

The effects of aging on accuracy and response time were examined in a letter discrimination experiment with young and older subjects. Results showed that older subjects (ages 60-75) were generally slower and less accurate than young subjects. R. Ratcliff's (1978) diffusion model was fit to the data, and it provided a good account of response times, their distributions, and response accuracy. The results produce similar age effects on the nondecision components of response time (about 50 ms slowing) and the response criteria (more conservative settings) to those from R. Ratcliff, A. Thapar, and G. McKoon (2001), but also show a reduced rate of accumulation of evidence for older subjects. The model-based approach has the advantage of allowing the separation of aging effects on different components of processing.

Classification, assessment, prevalence, and effect of personality disorder

A person-centered approach to moral judgment

DOI:10.1177/1745691614556679

URL

PMID:25910382

[本文引用: 1]

Both normative theories of ethics in philosophy and contemporary models of moral judgment in psychology have focused almost exclusively on the permissibility of acts, in particular whether acts should be judged on the basis of their material outcomes (consequentialist ethics) or on the basis of rules, duties, and obligations (deontological ethics). However, a longstanding third perspective on morality, virtue ethics, may offer a richer descriptive account of a wide range of lay moral judgments. Building on this ethical tradition, we offer a person-centered account of moral judgment, which focuses on individuals as the unit of analysis for moral evaluations rather than on acts. Because social perceivers are fundamentally motivated to acquire information about the moral character of others, features of an act that seem most informative of character often hold more weight than either the consequences of the act or whether a moral rule has been broken. This approach, we argue, can account for numerous empirical findings that are either not predicted by current theories of moral psychology or are simply categorized as biases or irrational quirks in the way individuals make moral judgments.

Acts, persons, and intuitions: Person-centered cues and gut reactions to harmless transgressions

Comprehensive review: Computational modelling of schizophrenia

DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.022

URL

PMID:28867653

[本文引用: 1]

Computational modelling has been used to address: (1) the variety of symptoms observed in schizophrenia using abstract models of behavior (e.g. Bayesian models - top-down descriptive models of psychopathology); (2) the causes of these symptoms using biologically realistic models involving abnormal neuromodulation and/or receptor imbalance (e.g. connectionist and neural networks - bottom-up realistic models of neural processes). These different levels of analysis have been used to answer different questions (i.e. understanding behavioral vs. neurobiological anomalies) about the nature of the disorder. As such, these computational studies have mostly supported diverging hypotheses of schizophrenia's pathophysiology, resulting in a literature that is not always expanding coherently. Some of these hypotheses are however ripe for revision using novel empirical evidence. Here we present a review that first synthesizes the literature of computational modelling for schizophrenia and psychotic symptoms into categories supporting the dopamine, glutamate, GABA, dysconnection and Bayesian inference hypotheses respectively. Secondly, we compare model predictions against the accumulated empirical evidence and finally we identify specific hypotheses that have been left relatively under-investigated.

Interpreting the parameters of the diffusion model: An empirical validation

DOI:10.3758/bf03196893

URL

PMID:15813501

[本文引用: 1]

The diffusion model (Ratcliff, 1978) allows for the statistical separation of different components of a speeded binary decision process (decision threshold, bias, information uptake, and motor response). These components are represented by different parameters of the model. Two experiments were conducted to test the interpretational validity of the parameters. Using a color discrimination task, we investigated whether experimental manipulations of specific aspects of the decision process had specific effects on the corresponding parameters in a diffusion model data analysis (see Ratcliff, 2002; Ratcliff & Rouder, 1998; Ratcliff, Thapar, & McKoon, 2001, 2003). In support of the model, we found that (1) decision thresholds were higher when we induced accuracy motivation, (2) drift rates (i.e., information uptake) were lower when stimuli were harder to discriminate, (3) the motor components were increased when a more difficult form of response was required, and (4) the process was biased toward rewarded responses.

Orbitofrontal cortex and its contribution to decision-making

DOI:10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094334

URL

PMID:17417936

[本文引用: 1]

Damage to orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) produces an unusual pattern of deficits. Patients have intact cognitive abilities but are impaired in making everyday decisions. Here we review anatomical, neuropsychological, and neurophysiological evidence to determine the neuronal mechanisms that might underlie these impairments. We suggest that OFC plays a key role in processing reward: It integrates multiple sources of information regarding the reward outcome to derive a value signal. In effect, OFC calculates how rewarding a reward is. This value signal can then be held in working memory where it can be used by lateral prefrontal cortex to plan and organize behavior toward obtaining the outcome, and by medial prefrontal cortex to evaluate the overall action in terms of its success and the effort that was required. Thus, acting together, these prefrontal areas can ensure that our behavior is most efficiently directed towards satisfying our needs.

Money, moral transgressions, and blame

DOI:10.1016/j.jcps.2013.12.002

URL

[本文引用: 1]

Two experiments tested participants' attributions for others' immoral behaviors when conducted for more versus less money. We hypothesized and found that observers would blame wrongdoers more when seeing a transgression enacted for little rather than a lot of money, and that this would be evident in observers' hand-washing behavior. Experiment 1 used a cognitive dissonance paradigm. Participants (N = 160) observed a confederate lie in exchange for either a relatively large or a small monetary payment. Participants blamed the liar more in the small (versus large) money condition. Participants (N = 184) in Experiment 2 saw images of someone knocking over another to obtain a small, medium, or large monetary sum. In the small (versus large) money condition, participants blamed the perpetrator (money) more. Hence, participants assigned less blame to moral wrong-doers, if the latter enacted their deed to obtain relatively large sums of money. Small amounts of money accentuate the immorality of others' transgressions. (C) 2013 Society for Consumer Psychology. Published by Elsevier Inc.

Modeling morality in 3-D: Decision-making, judgment, and inference

DOI:10.1111/tops.12382

URL

PMID:31042018

[本文引用: 8]

Humans face a fundamental challenge of how to balance selfish interests against moral considerations. Such trade-offs are implicit in moral decisions about what to do; judgments of whether an action is morally right or wrong; and inferences about the moral character of others. To date, these three dimensions of moral cognition-decision-making, judgment, and inference-have been studied largely independently, using very different experimental paradigms. However, important aspects of moral cognition occur at the intersection of multiple dimensions; for instance, moral hypocrisy can be conceived as a disconnect between moral decisions and moral judgments. Here we describe the advantages of investigating these three dimensions of moral cognition within a single computational framework. A core component of this framework is harm aversion, a moral sentiment defined as a distaste for harming others. The framework integrates economic utility models of harm aversion with Bayesian reinforcement learning models describing beliefs about others' harm aversion. We show how this framework can provide novel insights into the mechanisms of moral decision-making, judgment, and inference.

Computational substrates of social norm enforcement by unaffected third parties

DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.01.040

URL

PMID:26825438

[本文引用: 1]

Enforcement of social norms by impartial bystanders in the human species reveals a possibly unique capacity to sense and to enforce norms from a third party perspective. Such behavior, however, cannot be accounted by current computational models based on an egocentric notion of norms. Here, using a combination of model-based fMRI and third party punishment games, we show that brain regions previously implicated in egocentric norm enforcement critically extend to the important case of norm enforcement by unaffected third parties. Specifically, we found that responses in the ACC and insula cortex were positively associated with detection of distributional inequity, while those in the anterior DLPFC were associated with assessment of intentionality to the violator. Moreover, during sanction decisions, the subjective value of sanctions modulated activity in both vmPFC and rTPJ. These results shed light on the neurocomputational underpinnings of third party punishment and evolutionary origin of human norm enforcement.

Damage to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex affects tradeoffs between honesty and self-interest

DOI:10.1038/nn.3798

URL

[本文引用: 2]

Substantial correlational evidence suggests that prefrontal regions are critical to honest and dishonest behavior, but causal evidence specifying the nature of this involvement remains absent. We found that lesions of the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) decreased the effect of honesty concerns on behavior in economic games that pit honesty motives against self-interest, but did not affect decisions when honesty concerns were absent. These results point to a causal role for DLPFC in honest behavior.

Patients with basal ganglia damage show preserved learning in an economic game

DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-07882-8 URL [本文引用: 1]

The “proactive” model of learning: Integrative framework for model-free and model-based reinforcement learning utilizing the associative learning-based proactive brain concept

DOI:10.1037/bne0000116

URL

PMID:26795580

[本文引用: 2]

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a powerful concept underlying forms of associative learning governed by the use of a scalar reward signal, with learning taking place if expectations are violated. RL may be assessed using model-based and model-free approaches. Model-based reinforcement learning involves the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). The model-free system involves the pedunculopontine-tegmental nucleus (PPTgN), the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the ventral striatum (VS). Based on the functional connectivity of VS, model-free and model based RL systems center on the VS that by integrating model-free signals (received as reward prediction error) and model-based reward related input computes value. Using the concept of reinforcement learning agent we propose that the VS serves as the value function component of the RL agent. Regarding the model utilized for model-based computations we turned to the proactive brain concept, which offers an ubiquitous function for the default network based on its great functional overlap with contextual associative areas. Hence, by means of the default network the brain continuously organizes its environment into context frames enabling the formulation of analogy-based association that are turned into predictions of what to expect. The OFC integrates reward-related information into context frames upon computing reward expectation by compiling stimulus-reward and context-reward information offered by the amygdala and hippocampus, respectively. Furthermore we suggest that the integration of model-based expectations regarding reward into the value signal is further supported by the efferent of the OFC that reach structures canonical for model-free learning (e.g., the PPTgN, VTA, and VS).