1 引言

性别偏见(Sexism)是基于性别差异的先入为主的不公正态度。过去社会心理学界长期秉持Allport (1954)的“偏见是一种反感态度”的论调(Glick & Fiske, 1996; Glick et al., 2000), 性别偏见的消极态度属性深入人心。但是Glick和Fiske (1996)回溯历史研究发现, 对女性的客观贬低和主观好感往往是相随相伴的:男人们一边否定女性的能力与权利, 一边却向她们寻求情感亲密, 也更愿意向她们伸出援手, 即对女性同时存在消极和积极的认知评价与情绪情感体验。据此他们提出矛盾性别偏见理论(ambivalent sexism theory, AST), 指出为维持父权和生殖繁衍两方面需求, 性别偏见不仅包含对反传统角色规范的女性的厌恶贬损, 也包含对符合传统的女性的肯定赞扬: 这种矛盾态度的一体两面可区分为敌意性别偏见(hostile sexism, HS)和善意性别偏见(benevolent sexism, BS) (Glick & Fiske, 1996; Glick, Diebold, Baileywerner, & Zhu, 1997); 它们在同一个体身上是同时存在和相互补充的意识观念, 分别指向对传统性别角色规范违反的“坏女人”和遵从的“好女人”, 以共同维持父权社会结构(Glick et al., 1997; Sibley & Wilson, 2004; Glick & Fiske, 2001)。这一理论清晰地展示和扩充了性别偏见的内涵维度, 之后善意性别偏见得到研究者们的广泛关注。

善意性别偏见是指一类主观情感上爱护女性但是将她们限制在传统性别角色定位上的态度。根据Glick和Fiske (1996)开发的矛盾性别偏见量表(ambivalent sexism inventory, ASI), 善意性别偏见的心理结构包含父权保护(protective paternalism)、性别差异互补(complementary gender differentiation)和异性亲密(heterosexual intimacy)三个维度。持有者倾向于将女性视为需要保护、具备优良品德和寄托浪漫情感的妻子、母亲和恋爱对象等“美好而柔弱”的刻板形象, 并对符合这些角色规范的女性给予积极评价(Glick et al., 1997; 2000), 其本质是通过奖励符合男性需求的女性来巩固性别不平等(Glick & Fiske, 2001)。早期研究主要运用ASI量表考察矛盾性别偏见在各类群体中的水平差异、关联特质, 以及与人们对女性的认知评价的关系等(陈志霞, 陈剑峰, 2007)。相比敌意性别偏见, 善意性别偏见因表面上的主观好意和帮助保护行为难以被识别为偏见, 更容易为女性接受(Barreto & Ellemers, 2005)。对此研究者们提出警告, 善意性别偏见的隐蔽性使它宛如“天鹅绒手套里的铁拳” (Jackman, 1994), 令女性难以有效防范和应对(Glick & Fiske, 1996; Glick, et al., 1997; ; 2000; Barreto & Ellemers, 2005)。近年来, 大量实证研究考察了善意性别偏见在私人领域(private domain)和公共领域(public domain)不同情境中对女性权利的影响(Connor, Glick, & Fiske, 2018), 以及从女性个体心理层面解释其作用机制。当前对这部分研究尚缺少系统的文献回顾。基于这些影响呈现出贯穿女性生涯发展的连续性, 本文将采取当前职业心理学界提倡的个体与其多重系统背景(context)交互影响的生涯发展研究路径(Patton & Mcmahon, 2014), 从善意性别偏见对女性生涯发展的影响作用和女性感知应对的心理机制两方面进行梳理。另外, 性别偏见属于社会心理学和女性主义的交叉课题。从女性主义心理学视角对善意性别偏见的相关研究进行批判性思考, 可发现研究立场的客观性和价值中立性存在值得反思之处; 吸收借鉴女性主义的最新理论, 也有助于性别偏见的研究发展。下面我们将进行详细介绍和讨论。

2 BS对女性生涯发展的影响

女性的生涯发展有其独特性, 当前学界仍缺乏公认有力的解释理论(Patton & Mcmahon, 2014)。但近年来学者们的研究已经取得一些共识:女性的职业发展与其他生活内容具有不可分割性; 工作和家庭生活都是女性生涯发展的中心; 人力资本和社会资本是女性职业生涯发展的关键因素(O'Neil, Hopkins, & Bilimoria, 2008)。据此, 我们关注在家庭教育、婚姻角色分工以及职场竞争这些女性生涯发展的重要议题中, 善意性别偏见对女性的生涯目标、职业选择和职业发展产生的影响。

2.1 BS对女性生涯发展的影响机制

教育是人力资本的关键指标(O'Neil et al., 2008), 父母支持和教育资源会影响个体的生涯目标选择(Patton & Mcmahon, 2014)。一项对加拿大164对母女的配对调查研究显示, 母亲的BS水平能够正向预测青春期女儿的BS水平和对传统目标(如外貌和婚恋)的期望水平, 负向预测女儿的学业目标(获得学位)期望和学业成绩(Montañés et al., 2012)。这与其他研究发现女性的受教育水平和BS水平呈负相关的结果相符(Glick, Lameiras, & Castro, 2002)。展示了善意性别偏见在家庭教育中对女儿们的学业成就和生涯目标的消极影响, 且具有代际传承性。

家庭-工作冲突仍是当前女性生涯发展面临的关键难题, 关系倾向在女性的职业选择中具有重要影响(Patton & Mcmahon, 2014; O'Neil et al., 2008)。相关研究显示, 在婚恋关系中, 女性的BS水平越高, 对传统婚姻角色规范如“男主外, 女主内”的认同度越高, 也越愿意为支持伴侣事业牺牲自我职业发展, 且这一态度受到伴侣的BS水平的正向促进。例如, Chen, Fiske和Lee (2009)的调查研究显示, 男女的BS水平都显著正向关联“妻子支持男性事业是天职”的婚姻规范信念。Moya等人(2007)的研究发现, 当恋人反对她们从事涉及辅导危险男性或面试罪犯的实习工作时, 无论对方说明理由与否, 自身BS水平高的女性都更愿意接受这种限制。吕胜男(2009)访谈了三位国内女性的职业生涯, 她们讲述了自己为爱情或家庭放弃了职业发展的经历, 这一过程中体现出对善意性别偏见中父权保护和异性亲密维度的高度认同。Hammond和Overall (2015)研究发现, 高水平BS的女性会更愿意为伴侣的事业目标提供支持保障, 尽管并不会得到对等的回报。为什么女性会愿意这样“自我牺牲”?除了为交换男性的“父权保护”, 也是为维持亲密关系稳定付出的代价。Overall和Hammond (2018)在亲密关系中男女的BS的交互影响性模型中指出:男性的BS有利于亲密关系以及提升女性伴侣对BS的认同水平(Hammond, Overall, & Cross, 2016); 女性自身的BS则使她们在维持亲密关系稳定和追求事业成功中面临一种“鱼与熊掌不可兼得” (trade-off)的两难困境(Overall & Hammond, 2018)。现代社会中职业发展是个体社会经济地位的关键指标, 但BS水平高的女性会为了亲密关系稳定牺牲自我的这一权利主张。

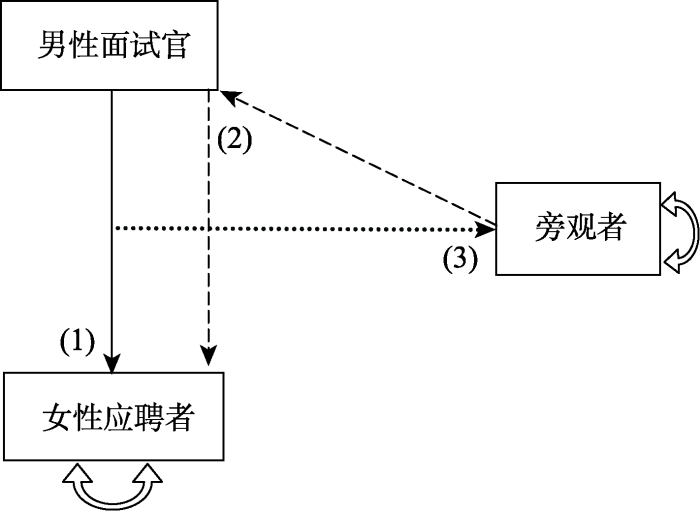

在职场情境中, 女性几乎在职业发展的每一个环节都遭遇性别歧视的困境(王海珍, 梅晓凤, 卫旭华, 2017)。目前围绕善意性别偏见对女性员工职业发展影响的研究可分为两类:一类是直接考察被试的BS水平与对女性员工评价的关系, 结果发现两者之间并无直接联系。例如Masser和Abrams (2004)的调查显示, 相比HS水平越高的被试会更倾向于对女性晋升候选人进行消极评价, 被试的BS水平的高低对女性晋升候选人的评价既无阻碍也无助益。在一项职业性别隔离的影响机制研究中, 高水平HS的被试们会倾向于选更多的女性进入慈善机构和选更多的男性进入证券机构, 但无论被试们的BS水平高低, 都不影响这种选择倾向(乔志宏, 郑静璐, 宋慧婷, 蒋盈, 2014)。这似乎说明职场领域中女性遭遇的性别歧视主要来源于人们的敌意性别偏见而非善意性别偏见。职场女性通常被认为是具有现代性精神、违反传统角色规范的形象(Connor et al., 2018), 她们更多地受到HS而非BS的作用, 这是符合理论逻辑的。但更可能是由于善意性别偏见和敌意性别偏见的表现形式和作用路径不同, 使得这种考察难以揭示它的影响。另一类研究采取了不同的研究路径, 得到了不同的结论:它们关注哪些职场行为属于善意性别偏见的范畴, 及对女性自身造成怎样的影响, 从而发现了善意性别偏见对女性员工产生影响的隐蔽性和间接性。例如有研究发现, 男性管理者给女下属比男下属更多的口头表扬, 分配挑战性更低的任务, 这种出于爱护女性的善意性别偏见行为会削弱女性员工在挑战性任务中获得成长的机会(Biernat, Tocci, & Williams, 2012; King et al., 2012)。还有一些研究通过模拟情景实验呈现具有BS属性的招聘情境, 对扮演女性应聘者的被试和作为旁观评价者的被试进行考察, 结果发现两者的认知行为都受到消极影响(见图1), 具体为:(1)女性应聘者自身的认知任务表现降低。在Dardenne, Dumont和Bollier (2007)的模拟化工厂招聘实验中, 无论招聘情境所属BS的种类是“父权保护”还是“性别差异互补”, 女性应聘者的认知任务得分都比HS和NS (no-sexism)情境下要低。研究者解释这是因为情境中的善意性别偏见对女性产生了分心干扰, 进而影响了对任务的工作记忆投入。(2)旁观者对女性应聘者的评价降低。Good和Rudman (2010)让美国大学生被试们阅读一份男性面试官对女性应聘者的面试记录, 其中面试官持有BS/HS/NS三种态度随机分配, 然后对女性应聘者的能力和可雇佣性进行评价。结果发现在HS和BS情境下被试对男性面试官的个人好感度越高, 对女性应聘者的能力和可雇佣性的评价越低; 在面试官持BS态度的情境下, 被试们的HS水平越高, 越会认为该女性应聘者不配得到BS的好处(申请管理岗位, 挑战男性主导地位, 违反了性别规范), 从而惩罚式地降低对她的评价。(3)旁观者对自身的评价也会受到消极影响。Bradleygeist, Rivera和Geringer (2015)继续使用Good和Rudman (2010)的实验材料, 考察阅读面试记录后被试们自身的自尊和职业抱负水平所受的影响。结果发现, BS情境下男女被试的工作表现自尊所受的影响差异不明显, 但是女性被试们相比在HS/NS情境下感受到更高的外表自尊, 男性被试则感受到更低的外表自尊。这两类研究共同证明了职场中的善意性别偏见不如敌意性别偏见的作用形式外显, 但产生深远的消极影响。

图1

图1

模拟招聘实验中的善意性别偏见的作用影响

注:根据Dardenne等(2007)、Good和Rudman (2010)、Bradleygeist等(2015)的研究整理。

以上研究揭示了社会系统中的善意性别偏见对女性生涯发展的作用机制:(1)具有欺骗性, 表现为对女性的正面态度和爱护行为, 实质是限制女性的社会角色和发展空间; (2)具有间接性, 主要通过女性的自我内化和遵从来实现, 如选择传统的生涯目标, 呈现出生涯发展动力不足甚至自我妨碍行为; (3)由于社会学习作用, 这种影响还具有对他人的溢出效应(Spillover Effect)。

2.2 BS对女性权利的“积极”作用

尽管绝大多数研究都指出善意性别偏见的消极影响, 也有研究者提议应辩证看待善意性别偏见对于女性关爱的积极成分(陈志霞, 徐荣华, 2013), 对此我们认为有必要进行专门澄清。在陈志霞和徐荣华(2013)的矛盾性别偏见与对职场性骚扰态度的关系研究中, 随机分配的实验材料向被试呈现了四种不同类型的女性受害者, 总体上被试的BS水平与反骚扰态度、支持受害者寻求法律援助呈显著正相关。但进一步分析发现, 当受害者为典型的传统性别角色的女性即最该获得BS保护的类型时, 被试的BS水平与骚扰者责备的正相关并不显著, 与受害者责备的负相关也不显著。文中BS的积极性是与HS相比较得出的。我们认为如果可以设置BS高低水平组进行区分比较, 结论会更有说服力。以及对善意性别偏见的评判, 其参照对象应该是无性别偏见, 而不该是和敌意性别偏见的“两弊相衡取其轻”。

有研究进一步挖掘了善意性别偏见伴随的“积极”行为的实际效用:Hideg和Ferris (2016)考察了善意性别偏见对就业性别平等政策的积极和消极影响, 积极影响是BS水平高的个体会在同情心中介下更倾向于支持就业性别平等政策, 消极影响是这种支持仅限于女性从事那些传统女性主导的职业。对此研究者评价道, 善意性别偏见表面上维护职场性别平等, 实际上促进职业性别隔离。Radke, Hornsey和Barlow (2018)比较了男女被试在女权行动和保护女性两种行动上的支持意愿, 发现男性被试的BS水平与支持保护女性的态度呈显著正相关; 在支持保护女性行动上, 男女被试同样积极, 但在支持女权行动上, 男性被试不如女性被试积极。进一步探究发现, 这种态度差异是因为女性更能感知性别不公, 而男性认为女权主义者想要获得比男性更多的权力。这验证了善意性别偏见的“好处”仅限于那些不威胁男性权力的女性及言行。对帮助行为类型和善意性别偏见关系的研究发现, BS水平越高, 男性被试更倾向对女性提供依赖性帮助而不是协助她们自主解决, 女性被试更期望寻求依赖性帮助而非自主解决(Shnabel, Baranan, Kende, Bareket, & Lazar, 2016)。拓展这一研究, 曹欣蕾和曹韵秋(2018)发现男性感知女性的能力和符合传统性别角色的程度会对帮助行为起到调节作用。鉴于依赖性帮助会促进群体内不平等(Chernyak-Hai & Waismel-Manor, 2019), 善意性别偏见下的性别帮助行为虽然表面有利, 但本质上起到的是强化传统性别角色规范的作用。

总体而言, 善意性别偏见表面的关爱态度和爱护行为像是甜蜜的诱饵, 如果女性被蒙蔽接受它, 就会在享受依赖男性的甜蜜同时, 付出让渡权利的代价。譬如为了得到男性的爱情, 主动放弃对教育和事业的投入; 接受上司的特别关照, 却失去职业成长的机会。待到女性发现生涯发展的空间越来越狭窄, 权利越来越受限时, 她已经丧失了夺回它们的能力。就如波伏娃(1949/2011)在《第二性》中所写:“当她发觉受到海市蜃楼的欺骗时, 为时已晚; 她的力量在这种冒险中已经消耗殆尽。”从这个意义上说, 善意性别偏见具有诱惑而危险的杀伤力, 比起“天鹅绒手套里的铁拳”, 更像是“蜜糖裹砒霜”。

3 女性受BS影响的心理机制

如前所述, 善意性别偏见对女性的消极作用, 主要是通过影响接受者自身的认知行为来实现。一般而言, 善意性别偏见水平越高的女性, 越倾向于认同传统角色规范(Chen et al., 2009; Overall & Hammond, 2018)。但也有研究发现, 女性对善意性别偏见缺乏有效识别(Barreto & Ellemers, 2005; Moya et al., 2007)。那么女性对善意性别偏见是被动接受, 还是主动认同?影响女性感知和应对善意性别偏见的相关因素是什么?为了揭示这其中的心理机制, 研究者们从女性对善意性别偏见的认知态度和应对动机两方面提出了理论解释。

3.1 女性对BS的认知态度

相关研究发现,女性自身的善意性别偏见水平受到文化背景、教育水平、年龄和个性特质等多因素影响。早期使用ASI量表的多项跨文化调查研究发现, 总体上男性的HS和BS水平都高于女性, 但在政治经济领域性别平等程度较低的地区比如许多发展中国家, 往往女性比男性持有更高水平的BS (Glick et al., 2000); Chen等人(2009)的中美大学生跨文化对比研究也发现, 中国女性比美国女性持有更高水平的BS。这似乎是因为越是在性别平等水平低的地区, 女性越是渴望得到善意性别偏见带来的“好处”, 比如经济上靠男性养家, 得到男性的保护等(Glick et al., 2000)。多项研究还发现女性的受教育程度与BS水平呈显著负相关(Lipowska et al, 2016; Glick et al., 2002)。新西兰的一项上万人大样本调查研究发现, 纵观一生, 男性的BS水平呈线性稳定增长趋势, 而女性的BS水平符合U型曲线模型, 且在大多数年龄段的横截面比较中呈下降趋势(Hammond, Milojev, Huang, & Sibley, 2018)。个体差异因素如人格特质也会影响对BS的态度, 如心理权利(psychological entitlement)远超已知的其他性别偏见预测因素(如低开放性)和相关协变量(如印象管理), 可有效预测女性的BS水平(Grubbs, Exline, & Twenge, 2014)。结合BS的量表内容如“在火灾中女性应该比男性先被救援” (Glick & Fiske, 1996), 以及外界对女性主义的常见批评是她们拒绝HS却渴望BS (Kilianski, 1998), 心理权利水平高的女性确实更可能将BS视为内群体所拥有的一种理所当然的特权而不是偏见。

尽管女性自身的善意性别偏见水平呈现个体差异, 但总体来说, 善意性别偏见难以被女性识别为偏见(Connor et al., 2018; Barreto & Ellemers, 2005; Moya et al., 2007)。这可能是因为社会认知偏差, 善意性别偏见不符合人们认知中性别偏见的心理原型(Barreto & Ellemers, 2005), 正如Glick和Fiske (1996)所言, 过去人们认为偏见是一种负向态度, 而BS的情感属性是主观善意的, 让人难以与偏见相联系。但是随着时代进步, 社会性别平等意识水平在提高, 这种认识也在逐渐发生改变(Rollero & Fedi, 2014)。其次, 女性对善意性别偏见的判断会受传递者的身份和动机等情境因素的影响。例如Moya等人(2007)发现, 来自丈夫的善意性别偏见不被认为是性别歧视的, 换成同事则不然; 相比基于个人化的理由(“因为我担心你”)给出的BS, 女性更容易判断出基于身份理由(“因为你是女人”)的BS是性别歧视的, 且女性自身的BS水平高低并不影响这种判断。此外, 女性对BS的理性认知判断与实际情感体验可能存在脱节, 这也会造成对BS的评估偏差(Bosson, Pinel, & Vandello, 2010)。

综合上述研究, 女性对善意性别偏见认知态度的影响因素多元而复杂, 随个体差异、文化背景和社会情境而变化。这提示我们应看到女性群体内部的异质性, 以及个体与其所处情境交互对性别偏见的动态性影响。

3.2 相关心理动机解释

不管女性对BS的认知态度是如何暧昧不明, 在行为结果上实实在在受到了它的影响, 表现出了自主消极认知和行为(Dardenne et al., 2007; Moya et al., 2007)。对于这其中的心理动因, 研究者们主要提出了以下几种代表性的理论解释。

(1)刻板印象威胁

刻板印象威胁是指当个体或群体感知到情境中有关所属群体消极刻板印象存在时, 由于担心和焦虑反而会验证自己或所属群体的消极刻板印象这一过程(管健, 柴民权, 2011)。由于善意性别偏见宣扬一种女性美好而“柔弱”的刻板印象(Connor et al., 2018), 其暗含的“女性能力弱”的假设, 可能会使女性感受到刻板印象威胁。在Dardenne等人(2007)的化工厂模拟招聘实验中, 尽管女性被试们在认知上不认为BS情境的招聘信息有性别偏见含义, 却感受到了和HS情境下一致的情绪不快, 研究者认为这是由于被试们内隐感知了BS的刻板印象威胁, 进而损害了她们在相关任务中的表现。在Rollero和Fedi (2014)考察矛盾性别偏见对大学生们自我职业抱负影响的研究中, 被试们阅读一份描述与自己性别相符的社会调查结果(HS/BS情境随机分布)后对自己将来成为领导者的可能性作出评估, 结果发现, 比起HS情境, BS情境下的女性被试们对成为管理和政治领域的领导者更不乐观。Dardenne等人(2007)的研究中还发现女性的高性别认同能够抵消HS情境下刻板印象的影响, 却对BS情境无效。结合Leicht等人(2017)的研究发现, 在反刻板印象情境下, 女性自身的性别认同显著正向预测领导者抱负水平; 性别刻板印象情境下, 这种关联受到女性主义认同的调节, 即只在高女性主义认同群体中能够继续保持。我们认为未来可考虑研究女性的性别认同和对女性主义认同的交互影响对克服BS刻板印象威胁的作用。

(2)成功恐惧论

蔡学青(2008)研究了我国女大学生的善意性别偏见与成就动机的关系, 发现被试们在“父权保护”维度上的得分与避免失败动机得分呈显著正相关, “性别差异互补”维度得分与追求成功动机得分呈显著正相关, 但总体上BS得分与成就动机总得分相关性不显著。这似乎是因为BS的“父权保护”抵消掉了“性别差异互补”带给女性的自信。研究进一步考察发现, 被试们对非传统女性职业(如计算机科学技术)的成功恐惧(fear of success)要显著高于传统女性职业(如英语语言文学) (蔡学青, 2008)。显然女性并非不渴望成功, 而是恐惧不符合社会期望的成功。与之相联系的是近年来提出的反弹回避模型(backlash avoidance model)理论, 女性因担心与传统性别角色不一致的行为引发外界的抵触情绪, 从而减少自我推荐行为及与之相关的可能成功(Kosakowska-Berezecka, Jurek, Besta, & Badowska, 2017)。从实质上讲, 都是一种女性对“成功的代价”怀有消极预期导致自我抑制的体现。

(3)制度正当化理论

制度正当化理论(system justification theory)认为, 表达善意行为是社会高级阶层对低级阶层实施统治的一种策略, 因为这样会使得后者更容易接纳自己的弱势地位, 甚至自发维护这种社会等级制度(Jost & Kay, 2005; Jackman, 1994)。善意性别偏见伴随的关爱保护等“好处”不仅为男性提供对自我性别优势地位的合理化借口“女性需要我们保护” (Glick & Fiske, 1996), 也会提高女性对自我社会身份地位的认同度(Jost & Kay, 2005)、对社会公平的认可度(Connelly & Heesacker, 2012)、生活满意度(Hammond & Sibley, 2011)和亲密关系的稳定度(Hammond & Overall, 2017), 尽管代价是权利的削弱和在关系中处于被动地位。这些都验证了善意性别偏见是一种对性别不平等进行合理化的意识形态工具(Mosso, Briante, Aiello, & Russo, 2013)。如果女性无法认识到善意性别偏见在群体层面的消极影响, 只关注表面上和个人水平的好处, 就会成为它的追随者甚至是维护者。Dardenne等人(2007)不客气地评论道, 从这个意义上来说, 女性是导致自我不利地位的“帮凶” (accomplices)。

以上几种理论从不同角度解释了善意性别偏见对女性的心理影响, 一定程度上揭示了女性应对善意性别偏见的困境。但在理论诠释上欠缺深度, 更多停留在个体层面的归因。当女性发现针对内群体的负面评价是真实存在的社会机制的映射, 当女性追求自我成功需要以遭受“惩罚”为代价, 这显然并非个体主观层面能解决的问题。制度正当化理论认为女性应该为自我的不利地位负一定责任(Dardenne et al., 2007), 却没有对女性群体内部进行区分, 比如是否具有选择空间, 所处文化背景的价值差异等。关于如何看待个体与社会的联系, 如何评价女性的自我能动性(self- agency), 女性主义早已有深刻全面的理论探讨, 值得心理学研究的学习借鉴。

4 女性主义心理学视角下的反思与启示

自女性主义对Sigmund Freud关于女性心理的理论观点提出质疑后, 女性主义心理学一直致力于批判和改进主流实证心理学貌似客观中立的背后隐蔽的男性话语霸权(Eagly, Eaton, Rose, Riger, & Mchugh, 2012)。善意性别偏见理论的提出是极具女权主义色彩的, 它揭示了以往被人们忽视甚至赞许的一种隐性偏见对女性造成的消极影响, 深化了对性别不公的认识。但是性别偏见不仅是心理现象, 更是一种社会现象, 涉及到权利公正的价值评判, 相关研究又是存在不足的。女性主义心理学的相关理论能够为这些研究提供反思和启示。

4.1 研究反思

(1)善意性别偏见理论在性别差异和性别平等关系中的价值预设。Glick和Fiske (1996)认为, 尽管善意性别偏见的子维度“性别差异互补”宣扬女性拥有男性所缺少的美好特质(如ASI量表中该维度项目为“女性比男性有更高的道德感”、“女人拥有男人缺乏的纯洁品质”、“女人比男人往往有更高的文化领悟力和更好的品位”, 见Glick & Fiske, 1996; Glick et al., 2000), 但“这些特质都是情感属性的, 而非能力属性的理性特质, 女性具有这些特质, 作用不过是弥补具有父权支配特质的男性的缺憾使他们更完美, 最终目的是强化性别差异的刻板化和对女性从属地位的合理化”。此处的逻辑论证中蕴含一种价值预设, 即认为那些“女性气质” (femininity)的社会价值是不如“男性气质” (masculinity)的。照此推理, 女性若要对抗善意性别偏见, 是否就该弱化自身和女性气质的联系, 转而积极向男性气质靠拢?有趣的是, 相关研究发现女性的确会采用这类社会再范畴化策略(王海珍 等, 2017), 但后果却是可能被人们认为违背传统性别角色规范, 从而招致属于敌意性别偏见的惩罚(Good & Rudman, 2010)。显然, 这里暗含的是一种以男性角色形象为标准的性别平等观, 其危险之处在于, 它秉持的依然是一种男权文化价值观。

性别平等的核心议题是如何看待性别差异。对此女性主义的不同派别持不同观点, 大致可分为两派, 一派主张忽视性别差异, 如早期自由女性主义争取以男性权力为标准的性别平等; 一派强调重新定义两性差异, 如激进女性主义坚持女性应该保持和发扬自己的特性(李银河, 2005)。后者以文化女性主义心理学家Carol (1993)为代表, 她在重构Kohlberg的道德判断实验基础上, 提出了应以女性的立场、以区别于男性话语范畴体系的“不同的声音”讲述她们自身的感受和经验, 以及提倡女性所具有的关怀道德(如重视关系、关心他人)对于整个社会的重要价值。当女性从研究的“客体”转为“主体”, 当“关怀” (女性气质)与“公正” (男性气质)具有同等价值, 关于性别偏见的研究将以全新的视角和价值呈现:善意性别偏见的“性别差异互补”维度对女性气质的赞美是否暗含不公正(Glick et al., 2001), “父权保护”与真正的关怀善意如何区分(Moya et al., 2007), 以及女性为了维护“异性亲密”在家庭-工作冲突中选择家庭是否具有正当性(Overall & Hammond, 2018), 相关论断都可以被反转。到后现代女性主义那里, 性别被视为社会文化建构的产物, 性别差异本身已经不重要, 重要的是如何被来自社会现实的政治权力建构(郭爱妹, 2001; 李银河, 2005)。以上这些女性主义的理论不仅丰富了对性别差异的价值认识, 也对性别偏见的内涵界定具有革新意义。

(2)如何正确评价女性在应对性别偏见中的角色, 她们是消极顺应的受迫害者, 还是具有自我能动性的积极适应者?研究立场决定了价值判断。例如, 有研究发现在预期遭遇性别沙文主义(类似于HS情境)的男性面试官时, 女性应聘者会提高自我言行外表的女性气质(Von Baeyer, Sherk, & Zanna, 1981), 对这一现象, 既可以认为女性是臣服于性别不平等的“帮凶” (Dardenne et al., 2007), 但也可看作是女性进行自我性别身份印象管理的积极区分策略(王海珍 等, 2017)。在对女性能动性的评价上, 女性主义内部也时常面临两难困境:肯定女性的自我主张, 有利于女性的自我赋权(self-empower); 但过分强调女性的个体力量, 也可能会招致将女性的不利处境进行个人层面归因的责难, 忽略其他社会因素的联系影响(Sischo & Martin, 2015; Negrin, 2002)。

后现代女性主义拒绝普遍化的女性身份立场, 将女性的能动作用与具体的社会文化、历史及政治背景联系起来, 从而为系统地认识女性生活的多重真理提供一个有益的分析框架(郭爱妹, 2001; 2006)。这为善意性别偏见的研究带来重要启示:首先, 应重视研究对象内部的异质性。先哲亚里士多德关于公正概念的名言:“公正不仅在于同类同等对待之, 还在于不同类不同等对待之。”善意性别偏见对家庭主妇的赞扬固然会令职业女性们坐立不安, 对经济独立女性的追捧是否也会令家庭主妇们倍感压力?如果仅从性别整体层面看待女性而忽视内部差异区分, 既是对女性自我话语权的忽视, 也难以客观全面地揭示性别偏见的作用真相。其次, 要避免将研究对象从她们的社会和历史背景中分离开来的“去情境化”。后现代女性主义认为性别不公并非仅仅由两性划分导致的, 而是受到其他更重要的社会身份(比如种族、民族、社会阶层和性取向等)的影响(李银河, 2005; 郭爱妹, 2001)。当前善意性别偏见的大多数研究都只看到单一性别身份对女性造成的影响(Montañés et al., 2012; Rollero & Fedi, 2014; Bradleygeist, et al., 2015), 这容易陷入本质主义的陷阱, 即把这些不平等简单归咎于性别差异, 而看不到背后实际运行的社会制度下各种身份地位和权力体系的交叉影响。

4.2 研究展望

4.2.1 未来研究趋势

(1)秉持开放性视角和多元价值观, 诠释性别偏见的全面内涵。心理学的全球化使学者们开始认识到文化的界限, 再自诩科学的研究者也无法避免自己身处的社会历史文化所隐含的价值预设的影响(Christopher, Wendt, Marecek, & Goodman, 2014)。例如主流实证心理学关于女性心理的知识, 不过是“中产阶级白人异性恋女性”的经验罢了(郭爱妹, 2006)。来自美国和西欧的主流心理学所传递的文化意识形态的“水土不服”, 促进了其他国家的本土心理学研究的兴起(Macleod, Marecek, & Capdevila, 2014)。这些都消弭了在性别研究中寻求普适性论断的可能性和必要性, 转向对多元文化和多种研究方法的拥抱。比如重视女性内部的异质性, 不同种族、不同阶级、拥有不同资源(经济、教育、政治)的女性遭遇的性别偏见可能不同, 相应的心理感知和经验诠释也会不同; 在对不同国家、民族群体的研究中, 不仅要“研究”这些文化, 还要从中“学习”, 从当地文化中寻找精神根源和诠释立场(Macleod et al., 2014)。

(2)超越简单性别因素归因, 采取交互型(intersectionality)研究视角。在性别偏见中, 个体原本的身份不是问题, 问题在于她们的身份是如何被社会化建构及由此遭到的对待(Macleod et al., 2014)。很多研究已发现性别差异主效应不如与有些社会因素的交互作用影响显著(Eagly & Wood, 2011), 比如相比性别因素, 个体的社会认知风格如认知闭合需要更能解释性别偏见的来源(Roets, Hiel, & Dhont, 2012); 丈夫在公开场合比私下场合更多地对妻子表达善意性别偏见, 显示了社会赞许性对性别偏见的影响(Chisango, Mayekiso, & Thomae, 2015)。近年来研究者们开始关注性别与社会情境和多重身份(种族、社会阶级和性取向等)的交互性影响, 这种影响并不只是简单地将不同维度划分的类型进行交叉, 更重要的是这些交叉之间的权力联系造成的后果, 虽然关于交互性研究的定义、概念和操作性方法都尚在发展之中, 但已开始出现该种视角的研究(Macleod et al., 2014)。

(3)在完善性别偏见的理论外, 积极探索消除这些负面影响的可行性方案。从研究的社会意义来看, 性别偏见在人类社会中如何传递、接受者如何感知和应对、以及造成了什么样的影响作用, 社会心理学解决的是“实然(is)”问题, 但经验层面的“实然”是无法导出“应然(ought)”的。性别偏见的研究不仅应关注个体的心理感受, 也该看到她们的实际处境, 提出相关应对建议和策略。女性主义在政治权利上的实践能够为心理学的相关研究提供参考。比如不同的法律和政策制度如何有效改善女性的地位处境(Hideg & Ferris, 2016); 男性的参与在改进性别平等中发挥的助力和阻力(Radke, Hornsey, & Barlow, 2018); 示例榜样和传媒舆论的信息对女性的自我赋权会产生怎样的影响等。这些需要从群体心理与群际过程领域加以考量。

4.2.2 中国文化背景

善意性别偏见在国内尚属新鲜概念。本文搜集到我国本土的相关研究寥寥, 且对该理论几乎都是照单全收, 没有探讨文化差异的适用性。一方面, 相较于发达国家, 我国性别平等水平在全球排名较低(The World Economic Forum, 2018), 对女性生涯发展的研究和性别平等意识的宣传长期处于滞后状态, 学界应积极关注社会现实境况并进行理论引导。《第三期中国妇女社会地位调查报告》和《2018年度妇女儿童热点舆情观察与分析》中, 都警示了近年来我国社会舆论中存在的传统性别观念的“回潮”现象(第三期中国妇女社会地位调查课题组, 2011; 中国妇女报编辑部, 2019-01-29)。善意性别偏见理论的研究传播, 将有助于对“男主外, 女主内”和“干得好不如嫁得好”等性别刻板印象的回击, 鼓励女性克服自我心理设限追求职业生涯发展。另一方面, 我国性别文化有其独特性。虽然中国传统儒家文化强调男女有别、男尊女卑, 但相关研究显示, 区别于西方个人主义文化对男性化特质的片面推崇, 我国集体主义文化背景下, 性别角色双性化的个体更受欢迎(蔡华俭, 黄玄凤, 宋海荣, 2008)。这体现了不同社会文化对性别特质有着不同的价值判断, 意味着中国本土的性别偏见有其独特面貌, 需要更多基于文化差异的适用性研究。未来应结合中国传统文化和社会热点现象, 积极探索我国性别偏见影响女性生涯发展的特殊性问题。以当前政府鼓励生育的政策为例, 这是否会影响社会对女性的性别偏见的类型和程度, 又会对女性职业生涯发展造成怎样的影响(杨芳, 郭小敏, 2017), 亟需更多研究予以关注和探讨。

5 结论

善意性别偏见的提出, 是对传统性别偏见理论的拓展革新。它揭示了一种以往被人们忽视的在表现形式和作用机制上都异于敌意性别偏见的偏见类型, 有助于全面呈现社会生活中性别不公的多种面貌和作用影响, 对我们防范性别歧视、促进性别平等具有重要意义。本文聚焦于善意性别偏见在家庭教育、婚恋角色分工和职场竞争等情境中对女性生涯发展影响的相关研究, 总结了善意性别偏见通过让女性产生自主消极认知行为来削弱女性的自我赋权和巩固男权社会结构的间接作用机制。善意性别偏见的“父权保护”、“异性亲密”和“性别差异互补”表现出的正面情感和关爱行为具有诱惑性, 却是“蜜糖裹砒霜”, 对性别平等具有隐蔽而危险的杀伤力。对女性感知和应对善意性别偏见的心理机制的相关研究发现, 女性对善意性别偏见缺乏有效识别和呈现出消极应对, 但当前相关研究更多停留在个人层面的解释归因, 在理论深度上存在欠缺。从女性主义心理学的视角审视善意性别偏见的相关研究, 在性别差异的价值判断、对女性自我能动性的诠释站位问题上, 值得结合女性主义相关理论进行反思和改进。女性主义心理学的最新思想对性别二元模式的消解和文化价值多元性的强调, 也为未来性别偏见的研究向本土化、差异化和情境化发展提供了丰富的积极启示。

参考文献

善意的性别偏见与依赖定向帮助的关系: 人际知觉的调节作用

The nature of prejudice

.

The burden of benevolent sexism: How it contributes to the maintenance of gender inequalities

The language of performance evaluations: Gender-based shifts in content and consistency of judgment

The emotional impact of ambivalent sexism: Forecasts versus real experiences

DOI:10.1007/s11199-009-9664-y

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

Research on affective forecasting indicates that people regularly mispredict the emotional impact of negative events. We extended this work by demonstrating several forecasting errors regarding women舗s affective reactions to ambivalent sexism. In response to a survey about sexism against women, students at a university in the Central U.S. (<i>N</i>舁=舁188) overestimated the negative impact of hostile sexism, and underestimated the negative impact of benevolent sexism, relative to women舗s reports of their actual experiences. Moreover, people mispredicted both the intensity of women舗s initial affective reactions to, and the duration of women舗s recovery following, ambivalent sexism. The data supported a model in which inaccurate estimates of initial intensity fully accounted for people舗s inaccurate estimates of recovery duration following ambivalent sexism.

The collateral damage of ambient sexism: Observing sexism impacts bystander self-esteem and career aspirations

Gendered help at the workplace: Implications for organizational power relations

Ambivalent sexism and power-related gender-role ideology in marriage

DOI:10.1007/s11199-009-9585-9

Magsci

[本文引用: 3]

Glick-Fiske舗s (<cite>1996</cite>) Ambivalent Sexism Inventory(ASI) and a new Gender-Role Ideology in Marriage (GRIM) inventory examine ambivalent sexism toward women, predicting power-related, gender-role beliefs about mate selection and marriage norms. Mainland Chinese, 552, and 252 U.S. undergraduates participated. Results indicated that Chinese and men most endorsed hostile sexism; Chinese women more than U.S. women accepted benevolent sexism. Both Chinese genders prefer home-oriented mates (women especially seeking a provider and upholding him; men especially endorsing male-success/female-housework, male dominance, and possibly violence). Both U.S. genders prefer considerate mates (men especially seeking an attractive one). Despite gender and culture differences in means, ASI-GRIM correlations replicate across those subgroups: Benevolence predicts initial mate selection; hostility predicts subsequent marriage norms.

The social nature of benevolent sexism and the antisocial nature of hostile sexism: Is benevolent sexism more likely to manifest in public contexts and hostile sexism in private contexts?

Critical cultural awareness: Contributions to a globalizing psychology

DOI:10.1037/a0036851

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

The number of psychologists whose work crosses cultural boundaries is increasing. Without a critical awareness of their own cultural grounding, they risk imposing the assumptions, concepts, practices, and values of U.S.-centered psychology on societies where they do not fit, as a brief example from the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami shows. Hermeneutic thinkers offer theoretical resources for gaining cultural awareness. Culture, in the hermeneutic view, is the constellation of meanings that constitutes a way of life. Such cultural meanings-especially in the form of folk psychologies and moral visions-inevitably shape every psychology, including U.S. psychology. The insights of hermeneutics, as well as its conceptual resources and research approaches, open the way for psychological knowledge and practice that are more culturally situated.

Why is benevolent sexism appealing? Associations with system justification and life satisfaction

Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: Consequences for women’s performance

Feminism and the evolution of sex differences and similarities

DOI:10.1007/s11199-011-9949-9

Magsci

Distrust between most evolutionary psychologists and most feminist psychologists is evident in the majority of the articles contained in this Special Issue. The debates between proponents of these perspectives reflect different views of the potential for transforming gender relations from patriarchal to gender-equal. Yet, with respect to the overall prevalence of sex differences or similarities, the articles in the Special Issue show that neither feminist psychologists nor evolutionary psychologists have uniform positions. Questions about how and if women and men differ are still under negotiation in the articles in this Special Issue as well as in other research related to evolutionary and feminist psychology. Clearer conclusions would be fostered by standardized metrics for representing male-female comparisons, more varied research methods for assessing both psychological and biological processes, greater diversity in populations sampled, and more researcher openness to taking into account findings that challenge their theories. Theoretical growth also is needed, especially to develop and integrate the many individual feminism-influenced theories represented in this Special Issue. To this end, we propose an integrative evolutionary framework that recognizes human culture in both ultimate and proximal causes of female and male behavior.

Feminism and psychology analysis of a half-century of research on women and gender

DOI:10.1037/a0027260

Magsci

[本文引用: 2]

Starting in the 1960s, feminists argued that the discipline of psychology had neglected the study of women and gender and misrepresented women in its research and theories. Feminists also posed many questions worthy of being addressed by psychological science. This call for research preceded the emergence of a new and influential body of research on gender and women that grew especially rapidly during the period of greatest feminist activism. The descriptions of this research presented in this article derive from searches of the journal articles cataloged by PsycINFO for 1960-2009. These explorations revealed (a) a concentration of studies in basic research areas investigating social behavior and individual dispositions and in many applied areas, (b) differing trajectories of research on prototypical topics, and (c) diverse theoretical orientations that authors have not typically labeled as feminist. The considerable dissemination of this research is evident in its dispersion beyond gender-specialty journals into a wide range of other journals, including psychology's core review and theory journals, as well as in its coverage in introductory psychology textbooks. In this formidable body of research, psychological science has reflected the profound changes in the status of women during the last half-century and addressed numerous questions that these changes have posed. Feminism served to catalyze this research area, which grew beyond the bounds of feminist psychology to incorporate a very large array of theories, methods, and topics.

The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism

The two faces of adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women

An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality

Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures

Education and catholic religiosity as predictors of hostile and benevolent sexism toward women and men

DOI:10.1023/A:1021696209949

Magsci

[本文引用: 3]

The relationships of education and religiosity to hostile and benevolently sexist attitudes toward women and men, as assessed by the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI; Glick & Fiske, 1996) and the Ambivalence Toward Men Inventory (AMI; Glick & Fiske, 1999), was explored in a random sample of 1,003 adults (508 women, 495 men) from Galicia, Spain. For both men and women (a) level of educational attainment negatively correlated with hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes, and (b) Catholic religiosity uniquely predicted more benevolent, but not more hostile, sexist attitudes. Although correlational, these data are consistent with the notion that active participation in the Catholic Church may reinforce benevolently sexist ideologies that legitimate gender inequality, whereas education may be effective in diminishing sexist beliefs.

When female applicants meet sexist interviewers: The costs of being a target of benevolent sexism

DOI:10.1007/s11199-009-9685-6

Magsci

[本文引用: 4]

American undergraduate participants (<i>N</i>舁=舁205) read an interview transcript and then evaluated male interviewers and a female job applicant to investigate perceptions of women who receive benevolent or hostile sexism (relative to non-sexist controls). As predicted, positive evaluations of the male interviewer in the benevolent and hostile sexist conditions negatively predicted participants舗 hiring decisions舒an effect that was fully mediated by low ratings of applicant competence. In accord with ambivalent sexism theory舗s claim that women who challenge male dominance are not eligible for protective paternalism, participants舗 hostile sexism scores predicted lower ratings of applicant competence and hireability, but only when the interviewer was a benevolent sexist. Implications for workplace discrimination are discussed.

Psychological entitlement and ambivalent sexism: Understanding the role of entitlement in predicting two forms of sexism

DOI:10.1007/s11199-014-0360-1

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

Recent research has shown that narcissistic men in the United States express more ambivalent sexism than their non-narcissistic counterparts. The present study sought to extend these findings by hypothesizing that psychological entitlement would be a predictor of ambivalent sexism but that that this relationship may vary by gender. Given entitlement's associations with hostility and aggression and the previously established link between narcissism and sexism in men, we hypothesized that entitlement would predict hostile sexism in men. Given that entitlement is characterized by a pervasive sense of deservingness for special treatment and goods, we expected that entitled women would endorse attitudes of benevolent sexism. These hypotheses were tested using two cross-sectional samples in the U.S.-a sample of undergraduates from a private university in the Midwest (N = 333) and a web-based sample of adults across the U.S. (N = 437). Results from regression analyses confirmed that psychological entitlement is a robust predictor of ambivalent sexism, above and beyond known predictors of sexism such as low openness and relevant covariates such as impression management. In addition, entitlement was a consistent predictor of benevolent sexism in women, but not in men, and a consistent predictor of hostile sexism in men, but not in women. These relationships were largely robust, persisting even when relevant covariates (e.g., socially desirable responding, trait openness) were controlled statistically, although in one sample the link between entitlement and hostile sexism in men was reduced to non-significance when benevolent sexism was controlled for statistically. Implications of these findings are discussed.

Why are benevolent sexists happier?

Benevolent sexism and hostile sexism across the ages

Benevolent sexism and support of romantic partner's goals: Undermining women's competence while fulfilling men's intimacy needs

Internalizing sexism within close relationships: Perceptions of intimate partners' benevolent sexism promote women's endorsement of benevolent sexism

Dynamics within intimate relationships and the causes, consequences, and functions of sexist attitudes

The compassionate sexist? How benevolent sexism promotes and undermines gender equality in the workplace

Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification

Benevolent sexism at work: Gender differences in the distribution of challenging developmental experiences

DOI:10.1177/0149206310365902

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

The current research draws from ambivalent sexism theory to examine potential gender differences in the quantity and quality of developmental work experiences. In a sample of managers in the energy industry, men and women reported participating in a similar number of developmental experiences (with comparable levels of support), but men rated these experiences as more challenging and received more negative feedback than did women. Similarly, a sample of female managers in the health care industry reported comparable amounts, but less challenging types, of developmental experiences than their male counterparts'. The results of three complementary experiments suggest that benevolent sexism is negatively related to men's assignment of challenging experiences to female targets but that men and women were equally likely to express interest in challenging experiences. Taken together, these results suggest that stereotype-based beliefs that women should be protected may limit women's exposure to challenging assignments, which in turn may partially explain the underrepresentation of women at the highest levels of organizations.

Wanting it both ways: Do women approve of benevolent sexism?

Self-presentation strategies, fear of success and anticipation of future success among university and high school students

Counter-stereotypes and feminism promote leadership aspirations in highly identified women

“Daughter and son: A completely different story”? Gender as a moderator of the relationship between sexism and parental attitudes

Feminism & psychology going forward

Reinforcing the glass ceiling: The consequences of hostile sexism for female managerial candidates

DOI:10.1007/s11199-004-5470-8

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

Previous research has established that benevolent sexism is related to the negative evaluation of women who violate specific norms for behavior. Research has yet to document the causal impact of hostile sexism on evaluations of individual targets. Correlational evidence and ambivalent sexism theory led us to predict that hostile sexism would be associated with negative evaluations of a female candidate for a masculine-typed occupational role. Participants completed the ASI (P. Glick & S. T. Fiske, 1996) and evaluated a curriculum vitae from either a male or female candidate. Higher hostile sexism was significantly associated with more negative evaluations of the female candidate and with lower recommendations that she be employed as a manager. Conversely, higher hostile sexism was significantly associated with higher recommendations that a male candidate should be employed as a manager. Benevolent sexism was unrelated to evaluations and recommendations in this context. The findings support the hypothesis that hostile, but not benevolent, sexism results in negativity toward individual women who pose a threat to men''s status in the workplace.

The role of legitimizing ideologies as predictors of ambivalent sexism in young people: Evidence from Italy and the USA

DOI:10.1007/s11211-012-0172-9

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

AbstractThe studies presented here focus on the relationship between legitimizing ideologies and ambivalent sexism. 544 Italian students (Study 1) and 297 US students (Study 2) completed several scales: social dominance orientation (SDO), system justification (SJ), political orientation, religiosity, and the Glick and Fiske (J Pers Soc Psychol 70(3):491–512, <span class="a-plus-plus citation-ref citationid-c-r6">1996</span>) Ambivalent Sexism Inventory. Zero-order correlations revealed all facets of ideological attitudes to be positively related to each other and correlated with ambivalent sexism. In particular, the SDO was related to both ideology components of SJ and political orientation and to ambivalent sexism (hostile and benevolent). Moderated regressions revealed that SDO has a positive impact on hostile sexism for men only, while SJ has a positive impact on hostile sexism for women only. While the first result was stable across the two studies, the last moderated effect has been detected only in Study 1. We discuss the results with respect to different facets of social ideologies and cultural differences between the two countries.

It’s for your own good: Benevolent sexism and women’s reactions to protectively justified restrictions

Intergenerational transmission of benevolent sexism from mothers to daughters and its relation to daughters’ academic performance and goals

DOI:10.1007/s11199-011-0116-0

Magsci

[本文引用: 2]

AbstractA questionnaire study addressed the intergenerational transmission of benevolent sexist beliefs (BS) from mothers to adolescent daughters and influences of BS on daughters’ traditional goals, academic goals (i.e., getting an academic degree), and academic performance. In addition, the role of mothers’ educational level and job status as predictors of their BS was explored. One hundred sixty-four pairs of female adolescents and their mothers from Granada (Spain) completed questionnaires independently. Hypotheses were tested in a path model. Results suggest that mothers’ BS is negatively predicted by their education but not their job status. Mothers’ BS predicted daughters’ BS, which in turn negatively predicted daughters’goal to get an academic degree and positively predicted daughters’ traditional goals. Daughters’ academic performance was positively predicted by their goal to get an academic degree and negatively predicted by mothers’ BS. Results are discussed in terms of the socializing influence of mothers’ sexist ideology on their daughters and its implications for the maintenance of traditional roles that perpetuate gender inequalities.

Women’s careers at the start of the 21st century: Patterns and paradoxes

DOI:10.1007/s10551-007-9465-6

Magsci

[本文引用: 3]

In this article we assess the extant literature on women舗s careers appearing in selected career, management and psychology journals from 1990 to the present to determine what is currently known about the state of women舗s careers at the dawn of the 21st century. Based on this review, we identify four patterns that cumulatively contribute to the current state of the literature on women舗s careers: women舗s careers are embedded in women舗s larger-life contexts, families <i>and</i> careers are central to women舗s lives, women舗s career paths reflect a wide range and variety of patterns, and human and social capital are critical factors for women舗s careers. We also identify paradoxes that highlight the disconnection between organizational practice and scholarly research associated with each of the identified patterns. Our overall conclusion is that male-defined constructions of work and career success continue to dominate organizational research and practice. <div class="AbstractPara"> <div class="">We provide direction for a research agenda on women舗s careers that addresses the development of integrative career theories relevant for women舗s contemporary lives in hopes of providing fresh avenues for conceptualizing career success for women. Propositions are identified for more strongly connecting career scholarship to organizational practice in support of women舗s continued career advancement.

How intimate relationships contribute to gender inequality: Sexist attitudes encourage women to trade-off career success for relationship security

Career Development and Systems Theory: Connecting Theory and Practice (3nd ed)

.

Changing versus protecting the status quo: Why men and women engage in different types of action on behalf of women

Is sexism a gender issue? A motivated social cognition perspective on men's and women's sexist attitudes toward own and other gender

DOI:10.1002/per.843

Magsci

[本文引用: 2]

The present research investigated the antecedents of ambivalent sexism (i.e., hostile and benevolent forms) in both men and women toward own and other gender. In two heterogeneous adult samples (Study 1: N?=?179 and Study 2: N?=?222), it was revealed that gender itself was only a minor predictor of sexist attitudes compared with the substantial impact of individual differences in general motivated cognition (i.e., need for closure). Analyses further showed that the relationship between need for closure and sexism was mediated by social attitudes (i.e., right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation), which were differently related to benevolent and hostile forms of sexism. In the discussion, it is argued that sexism primarily stems from individual differences in motivated cognitive style, which relates to peoples' perspective on the social world, rather than from group differences between men and women. Copyright (c) 2011 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

When benevolence harms women and favours men: The effects of ambivalent sexism on leadership aspiration

Help to perpetuate traditional gender roles: Benevolent sexism increases engagement in dependency-oriented cross-gender helping

Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes toward positive and negative sexual female subtypes

DOI:10.1007/s11199-004-0718-x

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

Expressions of hostile and benevolent sexism toward a female character whose behavior was consistent with either a positive (i.e., chaste) or negative (i.e., promiscuous) sexual female subtype were examined. Consistent with the theory that benevolent and hostile sexism form complementary ideologies that serve to maintain and legitimize gender-based social hierarchies, men expressed increased hostile, but decreased benevolent,sexism toward a female character who fit a negative subtype, whereas they expressed increased benevolent, but decreased hostile, sexism toward a female character who fit a positive subtype that was consistent with traditional gender roles. Furthermore, men<img src="/content/G5K4106V2X4VP804/xxlarge8217.gif" alt="rsquo" align="BASELINE" border="0">s sexual self-schema moderated expressions of hostile sexism across subtypes, whichsuggests that men who think of themselves in sexual terms (i.e., those who are sexuallyschematic) may be predisposed to (a) interpret information about women in sexual terms and categorize women into positive or negative sexual female subtypes on the basis of limited information, which leads to (b) increased hostile sexist attributions when womenare perceived as fitting a negative sexual subtype. These findings emphasize the role of both social dominance motives and the more subtle sociocognitive processes underlyinggender stereotyping in the expression of ambivalent sexism.

The price of femininity or just pleasing myself? Justifying breast surgery

The global gender gap report 2018

Impression management in the job interview: When the female applicant meets the male (chauvinist) interviewer