1 前言

自Goleman (1995)的畅销书《情绪智力》出版以来, 情绪智力(emotional intelligence, EI)备受学界和业界的青睐, 认为它是有效应对和处置各种难题的核心要素或品质特征。《哈佛商业评论》甚至开设了情绪智力专栏, 刊载了数十篇情绪智力专题研究论文。在业界, 也涌现出大量有关情绪智力的培训服务项目, 据估计几乎75%的世界500强公司都使用过情绪智力培训产品(Bradberry, Greaves, & Lencioni, 2009)。可见, 在公众视野中, 情绪智力即使不是决定成功的唯一品质, 也是最主要的核心素质。

在学界, 情绪智力研究常与亲社会性联系在一起。首先, 情绪智力因其良好的情绪调节能力, 有助于个体保持良好的情绪状态和心理健康(Burrus et al., 2012; Hansen, Lloyd, & Stough, 2009); 其次, 情绪智力有利于移情、合作行为等, 从而促成良好的人际关系(Reis et al., 2007); 再次, 情绪智力有助于个体应对职场压力, 获得较高的工作满意度和工作绩效(Ouyang, Sang, Li, & Peng, 2015; Lam & Kirby, 2002; Joseph, Newman, & O’Boyle, 2015)。此外, 从团队绩效来看, 情绪智力与人际互动的质量相关, 高情绪智力的团队, 其凝聚力越高、合作行为越多, 进而有助于团队绩效的提高(Jordan & Troth, 2004; Farh, Seo, & Tesluk, 2012); 等等。

既有研究表明, 情绪智力的确与积极结果高度相关, 比如良好的关系、优异的工作绩效等(Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, 2008)。但是, 对于这些指标, 情绪智力到底发挥了多大的作用, 它是否真的能有效地预测成功?一些学者敏感地提出了质疑。Salovey和Mayer (1990)在提出情绪智力概念时便指出“当个体的情绪技能被反社会意图操控时, 他们可能会创造操控性场景或在互动过程中损害他人利益” (P.198)。Salovey和Mayer虽较早地指出情绪智力被消极运用的可能性, 但他们并未进一步研究“谁会消极运用情绪智力”。Bass和Steidlmeier (1999)关于真、伪变革性领导的研究对此做出了探讨。真正的变革型领导使用情绪智力激励和鼓舞追随者, 真正关心如何提升组织效能; 而伪变革型领导以自我为中心, 为实现自我目标而运用情绪智力, 有时甚至以牺牲他人利益为代价。

随着研究的深入, 少数学者在Salovey和Mayer质疑的基础上讨论了“为什么情绪智力可能会存在负面效应” (Härtel & Panipucci, 2007; Jordan, Ashton-James, & Ashkanasy, 2006; Kilduff, Chiaburu, & Menges, 2010)。他们认为, 高情绪智力意味着拥有更多的情绪识别和情绪调控能力, 进而可能会为了个人利益而伪装、塑造自己的情绪以操控他人的感知和情绪。然而, 这些观点还停留在理论推导层面。最近, Davis和Nichols (2016)关于情绪智力负面效应的研究, 将视角拓展到了个体内的黑暗效应, 指出在特定条件下, 情绪智力对内可能导致自我易损性(例如, 高情绪智力者可能会更多地内化他人的职业压力)。

情绪智力的负面效应虽引起了一些学者的关注, 但相关研究仍非常不充分。因此, 本研究呼应Kilduff等(2010)“将情绪智力与可贵的道德品质相剥离”的号召, 聚焦于工作场所中情绪智力的负面效应, 深入探讨其背后的心理机制和理论基础, 并在分析该领域现有研究不足的基础上, 针对性地提出了情绪智力消极面的未来研究方向。

2 情绪智力的概念与结构

2.1 情绪智力的概念

现有的文献中, 关于情绪智力的界定主要存在两种视角。其一, 能力型情绪智力(ability emotional intelligence, AEI)流派, 认为情绪智力是与情绪活动有关的能力; 其二, 特质型情绪智力(trait emotional intelligence, TEI)流派, 有时也被称为混合情绪智力(mixed emotional intelligence)流派, 该流派将情绪智力视为个性和能力的结合体(Walter, Cole, & Humphrey, 2011)。

特质型情绪智力的概念把一些与“情绪”无关的内容(如品德和个性等)都包含在内, 一直都受到学术界对其概念界定过于宽泛和松散的批判(Wong & Law, 2002)。情绪智力的能力流派将情绪智力与人格特质进行了严格区分, 使用的测量工具具备更优的心理测量学特性(Daus & Ashkanasy, 2005)。故本研究倾向于认同能力型情绪智力的界定, 将情绪智力视为与情绪活动相关的一组技能, 涉及“准确地感知、评价和表达情绪的能力; 接近或产生促进思维的情绪能力; 理解情绪和情绪知识的能力” (Mayer & Salovey, 1997)。

2.2 情绪智力的结构与测量

Salovey和Mayer (1990)将情绪智力划分为四个不同的维度:(1)自我情绪评定(self emotional appraisal, SEA), 涉及个体理解自己的深层情绪并能够自然地表达这些情绪的能力; (2)他人情绪评定(others’ emotional appraisal, OEA), 指人们感知和理解周围人情绪的能力。(3)情绪调节(regulation of emotion, ROE), 即调节情绪的能力, 这使人们能够更快地从高兴或痛苦中恢复至正常状态。(4)情绪使用(use of emotion, UOE), 即使用情绪的能力, 该能力有助于指导个体进行建设性活动, 以及完善他们的表现。

Wong和Law (2002)开发的情绪智力自陈量表正是基于Salovey和Mayer的情绪智力结构模型, 量表维度与上述结构一致, 各维度均包含4个题项, 共16个题项。除了自陈量表, 还可采用任务测验的方式测量能力型情绪智力, 其中MSCEIT (Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, & Sitarenios, 2003)是认可度较高的任务测验。测验的计分标准有两种——群体标准(按照大样本的反应频数为标准记分)和专家标准(以专家的反应频数为标准计分)。依据测验得分与标准分的符合程度来评估情绪智力。

3 情绪智力的负面效应

情绪智力并非总是积极的, 理由在于:第一, 情绪智力是一种与情绪相关的能力, 它与其他任何技能一样, 既能服务于善良的意愿, 也能被非善良甚至邪恶的目的所利用(Grant, 2014); 第二, 人是复杂体, 不一样的个体有着不同的特质、动机和价值观, 以及他们与组织环境的互动也不尽相同(如高情绪智力者更擅长审时度势), 当这些因素与情绪智力共同作用时, 情绪智力的效应是大相径庭的。

表1 情绪智力的负面效应

| EI流派 | 测量工具1 | 结果变量 | 调节变量 | 研究者 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEI | MSCEIT | 压力(皮质醇水平) | 睾酮水平 | Bechtoldt & Schneider, 2016 |

| TEI | EQ-I; TEIQue | 焦虑、愤怒、精力的削弱 | Petrides & Furnham, 2003 | |

| AEI | SSEIT | 创伤后成长 | Li et al., 2015 | |

| AEI | MEIS; SSEIT | 沮丧、自杀念头、绝望 | 日常麻烦 | Ciarrochi et al., 2002 |

| TEI;AEI | TEIQue; MSCEIT | 心理适应、沮丧 | 家庭功能失调、经济损失 | Davis & Humphrey, 2012; Davis & Humphrey, 2014 |

| TEI | TEIQue | 使他人情绪变糟的倾向 | 宜人性 | Austin, et al., 2014 |

| AEI | MSCEIT | 夫妻关系质量 | Brackett et al., 2005 | |

| AEI | MSCEIT | 偏差行为 | 马基雅维利主义 | Côté et al., 2011 |

| TEI | MEIA | 作假行为 | 作假机会、 认知能力 | Tett et al., 2012 |

| AEI | SSI | 情绪操控 | 黑暗人格 | Nagler et al., 2014 |

| AEI | WEIT | 作弊行为 | Gentina, Tang, & Dancoine, 2018 | |

| TEI | TEIQue | 原发性精神病态、 继发性精神病态2 | Sample, 2017 |

注:该表在

1 在整理情绪智力负面效应相关研究的过程中发现情绪智力的概念流派、测量工具有所不同。这容易产生疑问:情绪智力的负面效应是由于情绪智力概念、或是测量工具的差异带来的吗?从现有的研究来看, 我们可以排除情绪智力负面效应单纯源于概念流派、测量工具的混用。然而, 概念和测量工具的不一致为情绪智力负面效应带来了多大的误差, 还需更多的研究来检验。

2精神病态(psychopathy)被定义为一种以反社会心理和行为为特征的人格特质。原发性精神病态(primary psychopathy)的特点是冷酷无情、操纵、自私和虚伪; 继发性精神病态(secondary psychopathy)的特点是参与冲动的行为和自我挫败的生活方式。

3.1 个体内的负面效应

3.1.1 情绪智力与身心健康

一些研究发现了高情绪智力者常常有更高的压力反应。Bechtoldt和Schneider (2016)研究了情绪智力和压力反应的关系以及睾酮的调节作用,选用皮质醇作为压力的生理指标, 结果发现, 在社会要求情境下, 高情绪智力者往往有更高的压力水平, 睾酮得分越高, 这种关系越强烈。另外, Bechtoldt和Schneider (2016)还指出高情绪智力者从这种高皮质醇水平中的恢复速度更慢。Petrides和Furnham (2003)的实验研究发现, 高情绪智力者能更快地感知到情绪, 然而, 在观看了沮丧的电影后, 高情绪智力者也报告了更高的焦虑、愤怒水平和更低的精力水平。

还有一些研究关注了情绪智力与心理疾病间的关系。 Li等(2015)以护理专业的学生为被试, 发现相较于中等水平情绪智力的学生, 那些拥有过高或者过低情绪智力的学生在面临童年创伤后的成长水平较低。Ciarrochi等(2002)发现, 当个体遇到更多日常的麻烦事(daily hassles)时, 高情绪智力常常导致高度的沮丧、自杀念头和绝望。类似地, Davis和Humphrey (2012, 2014)发现, 在家庭功能失调或者面临经济损失时, 高情绪智力者存在更高的心理适应问题和更高的沮丧水平。

3.1.2 情绪智力与绩效

当工作活动不需要情绪智力时, 情绪智力可能存在隐性代价(Grant, 2014)。例如, Joseph和Newman (2010)的一项元分析中, 综合分析了几百项研究中情绪智力和工作绩效的关系, 这些研究中的样本涉及191个不同岗位的上千名员工。结果表明, 情绪智力与工作绩效间并没有一致性的关系, 即当工作需要倾注大量的情绪时, 情绪智力越高, 绩效越好; 反之, 对于不需要倾注过多情绪的工作, 高情绪智力可能是缺点而非优点。Grant (2014)对情绪智力之于工作绩效可能的负面效应做出了解释, 即在无需过多情绪活动的工作中, 高情绪智力的员工在本应专心完成任务的时候, 却把注意力放在了情绪上。比如, 在分析数据或修理汽车的工作中, 察言观色会分散注意力。Khanna和Mishra (2017)也提出了类似的观点, 认为在对情绪需求较少的工作中(例如机械、科学研究和宇航等), 情绪智力并不利于工作绩效。

3.2 人际间的负面效应

3.2.1 情绪智力与人际操纵

情绪智力可能导致人际间的情绪操纵与欺骗。Brackett等(2005)研究了情绪智力与夫妻关系质量的关系, 研究发现, 相比于情绪智力都不是很高的夫妻, 夫妻二人都有高情绪智力时经常在夫妻关系质量上得分更低。该研究同时指出, 虽然夫妻两人情绪智力都低将导致糟糕的夫妻关系质量, 但当一人情绪智力高或两人情绪智力都高时, 这并不会显著改善夫妻关系质量。情绪操控也发生在非夫妻关系中, Austin等(2014)认为, 虽然情绪智力与使他人情绪变糟的倾向负相关, 但是宜人性起到边界调节的作用, 即当个体的宜人性较低时, 高情绪智力者更有可能使他人情绪变糟。类似地, Nagler等(2014)指出具有黑暗人格的个体更善于运用情绪技能操控他人。

3.2.2 情绪智力与人际间消极行为

有研究指出情绪智力导致了更多的人际间消极行为。Côté等(2011)的研究指出, 个性特征激发了相关的目标, 情绪能力帮助个体实现目标。他们通过两个研究探讨了情绪智力与道德同一性的交互作用对亲社会行为的作用, 以及情绪智力与马基雅维利主义的交互作用对人际偏差行为的影响。结果发现, 高情绪智力者既可能带来更多的亲社会行为, 也可能产生更多的人际偏差行为, 究竟产生何种效应取决于个体特质诱发了何种个人目标, 即, 具有道德同一性的高情绪智力者的亲社会行为更多, 而手段最险恶的员工正是高情绪智力的马基雅维利主义者。Côté等(2011)进一步指出, 情绪智力本身既不是正面的, 也不是负面的, 但却可以通过对情绪的有效监管帮助个体目标的实现, 这些目标可能是亲社会性的, 也可能是反社会性的。此外, Tett等(2012)的研究发现了情绪智力与作假行为之间的关系, 当个体有机会作假时, 具有高认知能力与高情绪智力的个体会表现出更多的作假行为。

4 情绪智力负面效应的机制探析

虽然上述研究一定程度上证实了情绪智力的负面效应, 然而鲜少有研究对其内部机制进行分析与解读。本研究对情绪智力负面效应的机制探析同样采用“个体内/人际间”维度。基于自我损耗理论和资源保存理论探讨情绪智力对个体自身的负面效应, 并结合情绪智力策略模型探讨情绪智力在人际间的负面效应。

4.1 自我损耗效应

一般而言, 在处理情绪事件时, 高情绪智力者的自我损耗程度应低于低情绪智力者。然而, 一些研究将高情绪智力与高内在损耗联系起来。例如, Davis和Humphrey (2012, 2014)指出, 在家庭功能失调或者面临经济损失时, 高情绪智力者存在更大的心理适应问题和更高的沮丧水平。为何高情绪智力反而会带来更高的内在损耗?

自我损耗理论(Ego Depletion Theory)对上述现象进行了阐释。该理论认为, 调控情绪和思维都会消耗心理能量, 而所有需要心理能量的活动使用的是同一种资源——自我控制资源, 之前的意志活动造成的自我控制资源的损耗将导致随后意志活动控制水平的下降(Baumeister, Bratslavsky, & Tice, 1998), 此即“自我损耗”现象。控制环境(controlling the environment)、控制自我(controlling the self)、做出抉择(making choices)和发起行动(initating action)等都属于意志活动(Baumeister et al., 1998)。情绪的评估、调节和使用是一种有意的控制行为, 亦会损耗自我控制资源, 进而影响随后的意志行为。

自我损耗理论虽对损耗效应以及其中所涉及资源进行了清晰的描述, 然而该理论无法解释“高情绪智力者为何消耗更多的自我控制资源”。故本文采用资源保存理论(Conservation of Resources Theory)的“资源投入-产出不平衡”角度来解释情绪智力自我损耗效应的内部机理。

高情绪智力者面临着更高的工作要求(非正式工作规范要求), 这种要求可能源于他人和自身的高期待。例如, 高情绪智力者很可能会被组织中那些与其有关联的个体的情绪所影响——帮助他们处理工作中的负面情绪(Toegel, Anand, & Kildiff, 2007)。高情绪智力者可能需要经常表达组织所需的积极情绪, 但这种情绪不太可能始终与其实际感受一致, 当发生冲突时, 高情绪智力者需要进行情绪调节以显示所需的积极情绪(Lin, Scott, & Matta, 2018)。Joseph和Newman (2010)的元分析结果“对于不需要倾注过多情绪的工作, 高情绪智力可能是缺点”可以据此做出解释, 当正式工作规范中不涉及情绪时, 低情绪智力者的日常工作中涉及较少的情绪活动, 而高情绪智力者因其自身和他人的高期待, 仍需处理大量的情绪事件, 因而会损耗其内在资源, 进而影响工作结果。

在实际的工作情境下, 尤其在高压力等消极环境下, 高情绪智力者所损耗的资源可能是无法恢复的。高情绪智力的个体更为深刻地感知负面事件, 并试图调用更多的资源来处理所遇到的困境。当所遇的困境得到顺利解决, 高情绪智力者所耗损的资源可得到一定程度的恢复, 但当所遇到的困境难以解决并且长期存在时, 高情绪智力者则将面临更严重的资源损耗和更艰难的资源恢复。这在一定程度上可以解释“高情绪智力者与心理疾病相关联”的现象(Ciarrochi et al., 2002; Davis & Humphrey, 2012, 2014)。

4.2 情绪智力策略模型

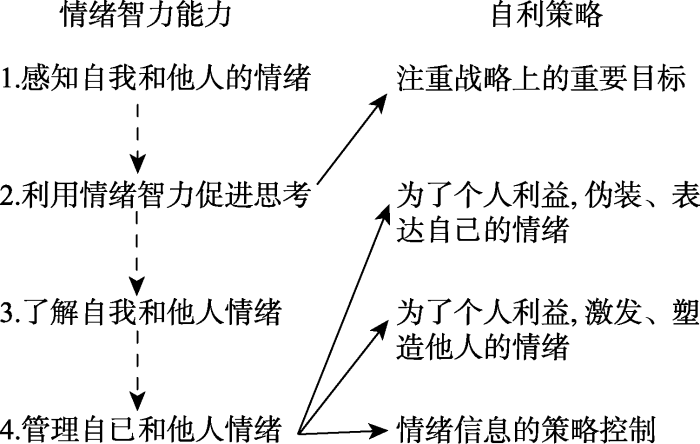

Kilduff等(2010)探讨了组织领域中, 人们如何通过使用情绪策略来控制互动结果, 从而在竞争中获得成功。基于能力型情绪智力的相关观点(如:Salovey & Mayer, 1990; Mayer & Salovey, 1997), Kilduff等(2010)提出, 在具有竞争压力的情境下, 情绪智力赋予个体四种情绪能力, 这些能力的策略性使用为个体谋取自身利益、获取竞争优势提供可能。图1展示了情绪智力能力与自利策略之间的关系, 同时也示眀了这些能力本身的层级关系。

图1

图1

情绪智力策略模型

注:该图依据Kilduff等(2010)的研究整理而得, 实线箭头表示采用自利战术所需的情绪智力能力; 虚线箭头表示更高层级的情绪智力能力包含更基本的情绪智力能力。这四种自利策略的排列顺序反映了高情绪智力者对他人操控的升级。

如图1所示, 第1种自利策略(关注战略上的重要目标)需要有感知自我和他人情绪的能力, 以及运用情绪智力促进思考的能力。简单地说, 高情绪智力者会有选择地利用这些能力来关注有利于或阻碍其晋升的人, 忽视无关人员的情绪。例如, 就下属视角而言, 在每个组织中, 负责控制绩效评估和加薪的主管的情绪很可能被下属仔细研究。

第2种自利策略(为了个人利益而伪装或表达情绪)运用了情绪智力中管理自我和他人情绪的能力。Kilduff等(2010)认为, 高情绪智力者可以故意塑造自己的情绪, 从而制造出对自己有利的印象, 或是为了实现目标, 表现出适宜、却有违内心感受的情绪。例如, 精明的扑克玩家可以用中性的表情来掩盖麻烦, 或者在面对平庸的牌时高兴地微笑。

就第3种自利策略(为了个人利益激发和塑造他人情绪)而言, 人们在并不完全明白自己的感受以及为何有这种感受时, 很容易受到其他人的可信解释的影响(Brodt & Zimbardo, 1981), 高情绪智力者则善于通过错误归因来改变事件的意义, 或是为了自身利益以微妙的方式分析不确定的情况。因此, 高情绪智力者常常帮助同事解释不明确的感觉, 这种解释充满了利己主义色彩。

就第4种自利策略(情绪信息的战略控制)而言, 高情绪智力者通过控制信息流动来影响他人声誉, 或是通过选择性的交流和资源分配来唤起他人不同的情绪反应, 以影响他们的决策和行为。例如, 高情绪智力的主管可能会过度奖励下属, 以利用下属在面对意外或不义之财时的负罪感和感激之情, 促使下属接受不吸引人的、不道德的, 甚至非法的任务。

Khanna和Mishra (2017)在Kilduff等(2010)的研究基础上进一步探讨了人际间情绪智力的负面效应。第一, 人际关系方面情绪智力的负面效应, 高情绪智力者通过控制自己的情绪来获得他人的信任, 再通过他人的信任控制信息流动, 进而来提升自己的利益。第二, 领导层面情绪智力的负面效应, 高情绪智力的主管可以使用情绪策略操控下属, 从而获得理想的结果, 而这可能对下属产生不良影响。Grant (2014)亦指出高情绪智力的领导可能出于自利的动机而操控他人, 对于他们而言, 情绪管理能力仅仅是实现目标的工具, 而目标则既可以是善的, 也可以是恶的。Bausseron (2018)则通过内容分析对Kilduff等(2010)的情绪智力的策略模型进行检验, 发现自我关注(self-focused)的领导更容易策略性地运用情绪能力。

5 总结与展望

尽管情绪智力的负面效应已引起一些学者的关注(Kilduff et al., 2010; Grant, 2014; 李一茗, 邹泓, 黎坚, 危胜男, 2016), 现有研究对此也做出了一些初步的尝试, 但这些研究成果大多缺乏深入的探讨或停留于理论层面。总的来看, 情绪智力负面效应的内在机制目前仍是一个“黑箱”, 对这一问题的探索无疑是一项既有挑战性又非常有趣的任务。因此, 结合上文对已有文献的梳理和相关理论的阐述, 我们提出如图2所示的情绪智力负面效应研究设想整合模型。该模型主要聚焦于以下几个方面的问题:

第一, 情绪智力负面效应的内在心理机制。已有研究常常将高情绪智力和心理疾病联系起来(Davis & Nichols, 2016; Furnham & Rosen, 2016), 然而, 这些研究大多只是做简单的相关分析, 并未对其原理进行深入探究。根据资源保存理论, 高情绪智力者因其较高的情绪能力, 将更多地关注组织中的情绪事件; 同时, 高情绪智力者会接收到来自他人及其自身的高期待和高要求, 他们在处理情绪事件时, 其处理态度、方式, 以及资源的调用都与低情绪智力者有所不同, 可能会产生“能力越大, 责任越大”的现象, 进而带来更多的自我损耗。未来的研究可将与资源消耗相关的变量(如:自我损耗、情绪耗竭和工作疲劳等)作为解释情绪智力与个体内在消极结果间的中介机制。

人际视角的情绪智力研究虽已尝试将情绪智力与自利策略结合起来, 但这些研究还停留在理论层面(Kilduff et al., 2010; Grant, 2014; Khanna & Mishra, 2017), 而在现今高度竞争的组织环境下, 那些善于辨别组织内部情绪暗流并对其采取行动的员工, 更可能取得成功。具体而言, 高情绪智力的员工善于利用信息的“生动效应”来达到自己的目的, 比如用动人心弦的语言描述事件, 运用具体的例子和吸引人的比喻, 而非仅仅依靠统计数据或理性的证据(Kilduff et al., 2010)。高情绪智力者的一个常用策略便是印象管理。例如, 高情绪智力的员工可以将其自利行为通过印象管理塑造成无私的行为(Kilduff et al., 2010)。未来的研究中, 我们需要进一步探讨非亲社会动机、非自主动机(如印象管理动机和自我提升动机等)在情绪智力和负面结果间的中介作用。

另外, 未来的研究还可以就“如何解读他人的策略性行为”来挖掘策略化使用情绪智力对观察者的消极影响。高情绪智力者的策略性行为带来何种结果很大程度上取决于观察者对此种行为的归因和评价。在情绪智力研究中, Dasborough和Ashkanasy (2002)的情绪和意向性归因模型提出了追随者关于其领导者意图(真诚或操纵)的归因, 导致他们将其领导者归类为真正的或伪变革的领导者。观察者对行为者意图的归因又将影响其后续的行为表现。结合社会学习理论(Social Learning Theory), 对行为者的消极归因与行为者的积极行为结果(如伪变革型领导为满足个人利益而采取的策略行为获得了积极结果)容易引起观察者的不公平感, 甚至产生对消极行为的模仿效应。未来的研究还需关注并研究如何避免“消极归因→消极行为模仿”这样一种恶性循环。

图2

图2

情绪智力负面效应的整合模型

注:1代表该变量主要在个体内层次产生影响; 2代表该变量主要在人际间层次产生影响; 因文献资料的不充分, 模型中未呈现群体层面情绪智力的负面效应。

第二, 情绪智力负面效应发生的情境条件。在现有的研究中, 有些学者将情绪智力与身心健康联系起来(Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, 2008), 也有学者将情绪智力与心理疾病联系起来(Davis & Nichols, 2016; Furnham & Rosen, 2016), 这表明情绪智力产生何种作用取决于行为者所处的特定情境。

未来的研究可以从个体所需面对的内外部压力环境来探讨高情绪智力者内在损耗所需的特定条件。这种压力既可以是客观压力环境, 也可以是心理上的压力环境。例如, 领导者便是一个重要的客观压力源, 高情绪智力者会尤为关注负责控制绩效评估和加薪的领导(Kilduff et al., 2010), 他们会对领导情绪的微妙暗示感兴趣, 包括领导的声音语调、面部表情和其他非语言手势, 这些信息暗含了领导的观点、偏好和潜在行为倾向(Sanchez-Burks & Huy, 2009)。

个体特性可能为高情绪智力者带来心理上的压力环境。例如, Snyder (1974)提出的自我监控概念, 他认为高自我监控者重视外界因素, 思考如何在特定情境中做出适宜行为, 依靠外界信息反馈调整自己的行为; 而低自我监控者则重视自身因素, 依据自身特点和内部状态等进行行为调节。实行自我监控的员工就如同“照镜子”——修正自我外显行为并注意观察他人的行为反馈。可推知, 当高情绪智力者的自我监控水平较高时, 极易产生较高的心理压力与内在损耗。

基于人际视角的情绪智力研究虽已开始将情绪智力与个体特征相结合, 认为两者共同作用时, 既有可能产生积极的效果, 也有可能带来负面效果。如Côté等(2011)的研究发现, 情绪智力与道德同一性的交互作用促进了亲社会行为; 而情绪智力与马基雅维利主义的交互作用却与人际偏差行为显著相关。但此类研究还很不充分。未来的研究可以继续深入挖掘“谁会策略化使用情绪智力”以及“何时会策略化使用情绪智力”。竞争性(competitiveness)作为一种个体特征, 它可以引发公民努力(citizenship efforts)并提高绩效, 也会引发蓄意破坏等不道德行为 (Charness, Masclet, & Villeval, 2013)。理论上, 当竞争性很高时, 高情绪智力者更容易运用其情绪智力进行策略行为以满足其个人利益。一项情绪智力研究一定程度上佐证了这一设想, 该研究运用囚徒困境来研究不同情绪智力者如何决策, 研究发现高情绪智力者在面临两难选择时, 更可能为实现个人利益最大化而选择竞争(Fernández-Berrocal, Extremera, Lopes, & Ruiz-Arande, 2014)。此外, 组织环境的竞争程度是否与策略化行为同样存在关联?这有待遇于未来更多的研究进行探讨和检验。

第三, 群体层面情绪智力的负面效应。综观情绪智力负面效应的实证研究和理论探讨, 可发现以往研究几乎不曾涉及群体层面情绪智力的负面效应。大多群体层面情绪智力研究对其影响效果持积极观点, 认为高情绪智力的群体通常冲突少、凝聚力高以及合作行为多, 进而产生更高的群体绩效(Dasborough & Ashkanasy, 2002; Wolff, 2005)。然而, 在组织的日常实践中, “融洽”却不作为的群体并不少见。显然, 已有研究不足以解释群体情绪智力可能带来的负面效应。未来群体层面情绪智力影响效果的研究需区分情绪智力对不同类型绩效(如任务绩效和创新绩效)的影响。正如Chamorro-Premuzic和Yearsley (2017)指出的, 情绪智力可能导致较低的创造力和创新潜力。此外, 简单的线性关系也许不能充分解释情绪智力与绩效间的关系, 未来的研究应尝试探讨两者间存在更为复杂关系的可能性。

参考文献

Associations of the managing the emotions of others (MEOS) scale with personality, the dark triad and trait EI

Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior

Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource?

The case for strategic emotional intelligence: Extension and test of a model

(

Predicting stress from the ability to eavesdrop on feelings: Emotional intelligence and testosterone jointly predict cortisol reactivity

Emotional intelligence and relationship quality among couples

Emotional intelligence 2.0. San Diego, CA:

Modifying shyness-related social behavior through symptom misattribution

Emotional intelligence relates to well-being: Evidence from the Situational Judgment Test of Emotional Management

The downsides of being very emotionally intelligent

The dark side of competition for status

Emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between stress and mental health

The Jekyll and Hyde of emotional intelligence: Emotion-regulation knowledge facilitates both prosocial and interpersonally deviant behavior

Emotion and attribution of intentionality in leader-member relationships

The case for the ability-based model of emotional intelligence in organizational behavior

The influence of emotional intelligence (EI) on coping and mental health in adolescence: Divergent roles for trait and ability EI

DOI:10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.05.007

Magsci

[本文引用: 2]

Theoretically, trait and ability emotional intelligence (EI) should mobilise coping processes to promote adaptation, plausibly operating as personal resources determining choice and/or implementation of coping style. However, there is a dearth of research deconstructing if/how EI impacts mental health via multiple coping strategies in adolescence. Using path analysis, the current study specified a series of multiple-mediation and conditional effects models to systematically explore interrelations between coping, EI, depression and disruptive behaviour in 748 adolescents (mean age = 13.52 years; SD = 1.22). Results indicated that whilst ability EI influences mental health via flexible selection of coping strategies, trait EI modifies coping effectiveness; specifically, high levels of trait EI amplify the beneficial effects of active coping and minimise the effects of avoidant coping to reduce symptomotology. However, effects were selective with respect to coping style and outcome. Implications for interventions are discussed alongside directions for future research. (C) 2012 The Foundation for Professionals in Services for Adolescents. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Ability versus trait emotional intelligence Dual influences on adolescent psychological adaptation

DOI:10.1027/1614-0001/a000127

Magsci

[本文引用: 2]

Emotional intelligence (EI) is reliably associated with better mental health. A growing body of evidence suggests that EI acts as a protective buffer against some psychosocial stressors to promote adaptation. However, little is known about how the two principle forms of EI (trait and ability) work together to impact underlying stressor-health processes in adolescence. One thousand one hundred and seventy British adolescents (mean age = 13.03 years; SD = 1.26) completed a variety of standardized instruments assessing EI; coping styles; family dysfunction; negative life events; socioeconomic adversity; depression and disruptive behavior. Path analyses found that trait and ability EI work in tandem to modify the selection and efficacy of avoidant coping to influence the indirect effect of stressors on depression but not disruptive behavior. Nevertheless, actual emotional skill (ability EI) appears dependent on perceived competency (trait EI) to realize advantageous outcomes. Findings are evaluated and discussed with reference to theoretical and practical implications.

Does emotional intelligence have a “dark” side? A review of the literature

Emotional intelligence, teamwork effectiveness, and job performance: The moderating role of job context

DOI:10.1037/a0027377

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

We advance understanding of the role of ability-based emotional intelligence (EI) and its subdimensions in the workplace by examining the mechanisms and context-based boundary conditions of the El performance relationship. Using a trait activation framework, we theorize that employees with higher overall El and emotional perception ability exhibit higher teamwork effectiveness (and subsequent job performance) when working in job contexts characterized by high managerial work demands because such contexts contain salient emotion-based cues that activate employees' emotional capabilities. A sample of 212 professionals from various organizations and industries indicated support for the salutary effect of El, above and beyond the influence of personality, cognitive ability, emotional labor job demands, job complexity, and demographic control variables. Theoretical and practical implications of the potential value of El for workplace outcomes under contexts involving managerial complexity are discussed.

When to cooperate and when to compete: Emotional intelligence in interpersonal decision- making

The dark side of emotional intelligence

Does Gen Z's emotional intelligence promote iCheating (cheating with iPhone) yet curb iCheating through reduced nomophobia?

Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ for character, health and lifelong achievement

The dark side of emotional intelligence

.

Emotional intelligence and clinical disorders

Evaluating the claims: Emotional intelligence in the workplace. In K. Murphy (Ed.), A critique of emotional intelligence: What are the problems and how can they be fixed?(pp. 189-210)

.

Managing emotions during team problem solving: Emotional intelligence and conflict resolution

Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model

Why does self-reported emotional intelligence predict job performance? A meta-analytic investigation of mixed EI

The dark side of emotional intelligence.In A. StachowiczStanusch, W. Amann, & G. Mangia (Eds.),Corporate Social Irresponsibility: Individual Behaviors and Organizational Practices(pp. 11-27)

Strategic use of emotional intelligence in organizational settings: Exploring the dark side

Is emotional intelligence an advantage? An exploration of the impact of emotional and general intelligence on individual performance

Nursing students’ post‐traumatic growth, emotional intelligence and psychological resilience

The dark side of transformational leader behaviors for leader themselves: A conservation of resources perspective

Human abilities, Emotional intelligence

What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey y D. Sluyter (Eds.).Emotional development and emotional intelligence: implications for educators(pp. 3-31)

Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2. 0

Is there a “dark intelligence”? Emotional intelligence is used by dark personalities to emotionally manipulate others

Organizational justice and job insecurity as mediators of the effect of emotional intelligence on job satisfaction: A study from China

Trait emotional intelligence: Behavioural validation in two studies of emotion recognition and reactivity to mood induction

Emotional intelligence predicts individual differences in social exchange reasoning

DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.045

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

AbstractWhen assessed with performance measures, Emotional Intelligence (EI) correlates positively with the quality of social relationships. However, the bases of such correlations are not understood in terms of cognitive and neural information processing mechanisms. We investigated whether a performance measure of EI is related to reasoning about social situations (specifically social exchange reasoning) using versions of the Wason Card Selection Task. In an fMRI study (<em>N</em>&#xxA0;=&#xxA0;16), higher EI predicted hemodynamic responses during social reasoning in the left frontal polar and left anterior temporal brain regions, even when controlling for responses on a very closely matched task (precautionary reasoning). In a larger behavioral study (<em>N</em>&#xxA0;=&#xxA0;48), higher EI predicted faster social exchange reasoning, after controlling for precautionary reasoning. The results are the first to directly suggest that EI is mediated in part by mechanisms supporting social reasoning and validate a new approach to investigating EI in terms of more basic information processing mechanisms.

Emotional intelligence

Emotional Intelligence and Decision- Making as Predictors of Antisocial Behavior (Unpublished doctorial dissertation)

Emotional aperture and strategic change: The accurate recognition of collective emotions

Self-monitoring of expressive behavior

Faking on self-report emotional intelligence and personality tests: Effects of faking opportunity, cognitive ability, and job type

DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.017

Magsci

[本文引用: 1]

We assessed the combined effects of cognitive ability, opportunity to fake, and trait job-relevance on faking self-report emotional intelligence and personality tests by having 150 undergraduates complete such tests honestly and then so as to appear ideal for one of three jobs: nurse practitioner, marketing manager, and computer programmer. Faking, as expected, was greater (a) in higher-g participants, (b) in those scoring lower under honest conditions (with greater opportunity to fake), and (c) on job-relevant traits. Predicted interactions accounted for additional unique variance in faking. Combining all three factors yielded a "perfect storm" standardized difference of around 2, more than double the overall .83 estimate. Implications for the study of faking are discussed. (C) 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Emotion helpers: The role of high positive affectivity and high self-monitoring managers

Emotional intelligence: Sine qua non of leadership or folderol?

Emotional competence inventory, Technical manual

The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude, An exploratory study